Abstract

Aims

Osteopontin (OPN) and osteoprotegerin (OPG) are bone metabolism biomarkers potentially associated with nerve function. We evaluated the association of cardiovascular autonomic nerve function, OPN, and OPG in 50 individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Methods

RR-variation during deep breathing (i.e., mean circular resultant (MCR) and expiration/inspiration (E/I) ratio) was used to assess parasympathetic nerve function. Participants’ demographics, HbA1c, 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), BMI, HOMA-IR, calcium, parathyroid hormone, creatinine, OPN, and OPG were determined.

Results

Using stepwise multiple linear regression analysis with MCR or E/I ratio as the dependent variable, OPN was independently associated with reduced autonomic function. A previous report showed a significant association of cardiovascular autonomic function with age, 25(OH)D insufficiency, and the interaction of age × 25(OH)D insufficiency. Here we report a novel association for OPN and its interaction with age indicating that for those who are younger, elevated OPN levels are related to a greater loss of autonomic function (MCR model R2 = 0.598, p < 0.001; E/I model R2 = 0.594, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Our results suggest that OPN is associated with reduced parasympathetic function, particularly in younger individuals with T2DM. Further studies are needed to determine if OPN is neuroprotective, involved in the pathogenesis of autonomic dysfunction, or a bystander.

Keywords: Osteopontin, Osteoprotegerin, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Cardiovascular autonomic nerve function, Parasympathetic nerve function

1. Introduction

Osteopontin (OPN) and osteoprotegerin (OPG), two bone metabolism biomarkers, are key elements in vascular remodeling and have been shown to be elevated in various disease states (e.g., hypertension) (Stepien et al., 2011; Tousoulis et al., 2013). OPN is a multifunctional protein with pleiotropic physiological functions. It is expressed in multiple human cell types (e.g., endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells) and in cells of the nervous system in rodents (Jander et al., 2002; Stepien et al., 2011; Wright et al., 2014). OPN plays a role in both acute and chronic inflammation (Mazzali et al., 2002). Elevated plasma levels of OPN have been reported in individuals with various neurodegenerative diseases (Brown, 2012). OPG is a secretory glycoprotein and a member of the tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor family (Guzel et al., 2013). OPG production occurs in many tissues including bone, endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells. Normally, it circulates in the blood at lower levels than in the tissues (Guzel et al., 2013) but elevated circulating levels of OPG have been reported in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), particularly in the presence of microvascular complications (Knudsen et al., 2003).

Diabetes is a leading cause of neuropathy with sensorimotor and autonomic neuropathies being the two main types. Persons with cardiovascular autonomic nerve dysfunction may suffer from orthostatic hypotension, exercise intolerance, intraoperative instability, silent myocardial ischemia, and increased risk of mortality (Maser & Lenhard, 2003; Vinik, Erbas, & Casellini, 2013). The etiology of diabetic neuropathy is multifactorial with metabolic, neurovascular, and inflammatory components. Three studies in persons with diabetes have demonstrated an association between higher OPG levels and peripheral neuropathy (Nybo, Poulsen, Grauslund, Henriksen, & Rasmussen, 2010; Tavintharan et al., 2014; Terekeci et al., 2009). OPN, in rodents, has been shown to be upregulated in denervated motor pathways with increased OPN protein expression in denervated Schwann cells following nerve injury (Wright et al., 2014). Schwann cell expression of OPN regulated by axon-derived signals has been demonstrated in sural nerve biopsies in humans (Jander et al., 2002). Given that there is a paucity of studies in humans that have explored an association with cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy and glycoproteins involved in bone homeostasis, the objective in this study was to determine if there is an association between cardiovascular autonomic nerve fiber function, OPG, and OPN.

2. Subjects and methods

2.1. Subjects

Individuals with T2DM (n = 50) were evaluated at the Diabetes and Metabolic Research Center, Christiana Care Health System, Newark, DE, USA. Participants in this study cohort have been previously described (Maser, Lenhard, Sneider, & Pohlig, 2015; Maser, Lenhard, & Pohlig, 2015). Here we report data pertaining to the association among OPN, OPG, and autonomic function. In brief, participants were eligible for the study if they were ≥18 years old with T2DM. Individuals were excluded if they had: (1) a history of known cardiac problems (e.g., myocardial infarction, acute myocardial ischemia, percutaneous coronary interventions, etc.); (2) changes (e.g., change in dose) in vitamin D, antidiabetes and antihypertensive medications 2 months before participation in the study; and (3) stage 3b or greater chronic kidney disease. This study had approval of the Institutional Review Board of Christiana Care Corporation and each participant gave written informed consent before participating in the study.

2.2. Cardiovascular autonomic function tests

Autonomic function was performed following an overnight fast. Participants were asked not to take any prescribed or nonprescription medications, not to consume tobacco products, caffeine-containing and alcoholic beverages, and not to engage in any vigorous exercise 8–10 h prior to testing. Cardiovascular autonomic function (i.e., RR-variation during deep breathing) was measured using the ANS2000 ECG Monitor and Respiration Pacer (DE Hokanson, Inc., Bellevue, WA, USA), as previously described (Maser & Lenhard, 2003). In this study, RR-variation during deep breathing performed for six minutes was measured by vector analysis (i.e., mean circular resultant [MCR]) and by the expiration/inspiration (E/I) ratio of the first six breath cycles. The MCR is resistant to effects of ectopic beats, whereas the E/I ratio is affected by ectopic beats (Schumer, Joyner, & Pfeifer, 1998). In this study cohort, the E/I results for six participants were labeled as missing.

2.3. Blood analytes

Specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were used for the measurement of OPG (ALPCO, Salem, NH, USA) and OPN (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Samples for OPG, OPN, leptin, and adiponectin were analyzed at the Nemours Biomedical Research & Analysis Laboratory, Jacksonville, FL, USA. The measurement of other analytes (i.e., 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], insulin, C-peptide, glucose, parathyroid hormone, calcium, serum creatinine, leptin, adiponectin, and HbA1c) and the method for calculating homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) have been previously reported in detail (Maser, Lenhard, Sneider, et al., 2015; Maser, Lenhard, & Pohlig, 2015).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Descriptive data are reported as mean ± SD and for those variables non-normally distributed the median ± semi-interquartile ranges are also provided. Pearson and Spearman rank correlation coefficients were used to evaluate potential bivariate associations between bone metabolism biomarkers (i.e., OPN, OPG), demographics (e.g., gender, BMI), metabolic parameters (e.g., HbA1c, HOMA-IR, parathyroid hormone, calcium, serum creatinine, leptin, total adiponectin, 25(OH)D insufficiency (i.e., <75 nmol/L)), and measures of cardiovascular autonomic function. Stepwise linear regression procedures, where the dependent variables were MCR or E/I ratio, were used to assess for potential independent associations of OPN, OPG, demographic and metabolic parameters. Normality was tested and if violated, a natural logarithmic transformation or nonparametric test was used.

3. Results

Table 1 provides participants’ clinical characteristics. Oral anti-diabetes agents were used by 48% of the study cohort, 12% used insulin/injectable agents, while 40% used both. Twenty-six percent had peripheral neuropathy determined via physician diagnosed signs and symptoms, while 14% were taking medications used to treat neuropathy.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the participants (n = 50).

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Median ± SIQRa |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63 ± 10 | – |

| Duration (years) | 13 ± 8 | 13 ± 5 |

| Male/female (n) | 21/29 | – |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 125 ± 13 | – |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 73 ± 7 | – |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.3 ± 1.2 | 7.0 ± 0.7 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 56 ± 13 | 53 ± 8 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 32.7 ± 5.3 | – |

| HOMA-IR | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 1.0 |

| Leptin (μg/L) | 22.9 ± 17.2 | 15.7 ± 11.9 |

| Total adiponectin (mg/L) | 6.9 ± 5.4 | 5.9 ± 2.1 |

| 25-hydroxyvitamin D (nmol/L) | 75 ± 27 | – |

| Parathyroid hormone (ng/L) | 36 ± 16 | – |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 2.4 ± 0.1 | – |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 75.7 ± 22.3 | 70.7 ± 13.3 |

| Osteoprotegerin (pmol/L) | 5.0 ± 2.0 | – |

| Osteopontin (ng/mL) | 64.5 ± 21.7 | 56.8 ± 12.4 |

HOMA-IR: homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance.

Median and Semi-Interquartile Ranges (SIQR) are provided for variables that were non-normally distributed.

Significant Pearson correlations for OPG levels included leptin (r = 0.30, p = .037), calcium (r = 0.33, p = .021), gender (r = 0.40, p = .004), and MCR (r = −0.30, p = .036). Significant Spearman rank correlations for OPN levels included systolic blood pressure (r = 0.33, p = .018), calcium (r = 0.31, p = .027), and OPG (r = 0.29, p = .039).

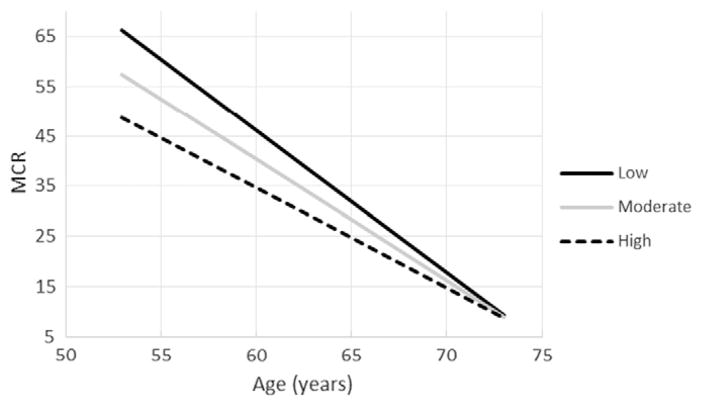

Stepwise linear regression selection procedures (Table 2) were performed regressing the MCR or E/I ratio on potential independent variables which included age, gender, BMI, HOMA-IR, HbA1c, leptin, total adiponectin, parathyroid hormone, calcium, serum creatinine, 25(OH)D insufficiency, OPG, and OPN. We had previously reported that age, 25(OH)D insufficiency, and their interaction were significantly associated with both measures of nerve function (Maser, Lenhard, & Pohlig, 2015). The stepwise procedure returned a final model of not only age, 25(OH)D insufficiency, and their interaction but also included OPN as a significant variable. OPG, however, was not selected as a significant covariate. Since it was previously shown that age interacted with 25(OH)D insufficiency, the interaction of age with OPN was also included in the model. It should be noted that the age by OPN interaction was significant for the E/I model and was borderline statistically significant for MCR (p = 0.087) (Table 2; Figs. 1 and 2). Low, moderate, and high levels of OPN as shown in Figs. 1 and 2 were determined via post-hoc probing of the moderation employing the simple slopes approach recommended by Aiken & West (1991) using the mean, +1, and −1 standard deviation. As can be observed in the figures, the interaction of age and OPN indicates that the association between higher levels of OPN and reduced parasympathetic nerve function is greater for those who are younger, while adjusting for 25(OH)D insufficiency and its interaction with age. With the MCR as the dependent variable, the F(5,44) = 13.110, p < 0.001, model R2 = 0.598, and adjustedR2 = 0.553. With the E/I ratio as the dependent variable, the F(5,38) = 11.127, p < 0.001, model R2 = 0.594, and adjustedR2 = 0.541.

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression models for measures of cardiovascular autonomic function.

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variables | Regression Coefficient | Standard Error | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCR | Age (years) | −3.684 | 0.875 | <0.001 |

| 25(OH)D insufficiency | −134.021 | 31.307 | <0.001 | |

| Age × 25(OH)D insufficiency | 1.730 | 0.484 | 0.001 | |

| OPN (ng/mL) | −1.441 | 0.656 | 0.033 | |

| Age × OPN | 0.020 | 0.011 | 0.087a | |

| E/I ratio | Age (years) | −0.026 | 0.005 | <0.001 |

| 25(OH)D insufficiency | −0.920 | 0.199 | <0.001 | |

| Age × 25(OH)D insufficiency | 0.013 | 0.003 | <0.001 | |

| OPN (ng/mL) | −0.011 | 0.004 | 0.007 | |

| Age × OPN | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.018 |

Variables not selected in the final stepwise linear regression models were: gender, body mass index, homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance, HbA1c, leptin, total adiponectin, parathyroid hormone, calcium, serum creatinine, and osteoprotegerin.

MCR: mean circular resultant.

E/I ratio: expiration/inspiration ratio.

OPN: osteopontin.

25(OH)D insufficiency: 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels <75 nmol/L.

Interaction terms: age × 25(OH)D insufficiency; age × OPN.

Along with those selected by the stepwise procedure, the OPN by age interaction was also included.

Fig. 1.

Age and mean circular resultant (MCR) for individuals with low (42.8 ng/mL), moderate (64.5 ng/mL), and high (86.2 ng/mL) levels of osteopontin. It should be noted that the lines in the figure are adjusted for 25-hydroxyvitamin D insufficiency and its interaction with age.

Fig. 2.

Age and expiration/inspiration ratio (E/I ratio) for individuals with low (42.0 ng/mL), moderate (64.4 ng/mL), and high (86.7 ng/mL) levels of osteopontin. It should be noted that the lines in the figure are adjusted for 25-hydroxyvitamin D insufficiency and its interaction with age.

4. Discussion

We investigated whether cardiovascular autonomic function is associated with circulating bone metabolism biomarkers OPG and OPN in persons with T2DM. This study showed that OPN levels and the interaction with age had a significant association with reduced parasympathetic nerve function particularly in younger individuals, while adjusting for 25(OH)D insufficiency. It is well known that nerve function declines with age. We had previously reported an association of age, 25(OH)D insufficiency, and their interaction with cardiovascular autonomic nerve function (Maser, Lenhard, & Pohlig, 2015).

The pathogenesis of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy is complex, involving a cascade of pathways activated by hyperglycemia that potentially leads to neuronal ischemia and cell death (Dimitropoulos, Tahrani, & Stevens, 2014). Metabolic insult and compromised nerve vascular blood supply have been implicated in the pathogenesis with several potential etiologies previously suggested (Sytze Van Dam, Cotter, Bravenboer, & Cameron, 2013; Vinik, Strotmeyer, Nakave, & Patel, 2008). Although the mechanism is not clear, the results of this study suggest an association of OPN and cardiovascular autonomic function. Previous studies in rodents have demonstrated, via immunohistochemistry, that OPN protein is distributed throughout the central nervous system, with other findings indicating that OPN may function in both the motor and sensory systems (Suzuki, Sato, & Ichikawa, 2012). Meller et al. (2005) demonstrated that the incubation of OPN with cortical neuron cultures protected against hypoxic cell death. OPN may also protect cells from undergoing apoptosis (Mazzali et al., 2002), with premature apoptosis and aberrations in neuronal apoptosis having been implicated in the pathogenesis of neuropathy (Ekshyyan & Aw, 2004). Thus, it is possible that OPN may possess neuroprotective functions. The association between increased OPN levels and reduced nerve function in our study may therefore be related to a potential increase in OPN synthesis as part of a compensatory mechanism (i.e., protective response) to limit nerve damage.

Neuronal ischemia resulting in nerve dysfunction may also be associated with elevated levels of OPN. OPN can modulate the proliferation, migration, and accumulation of vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells in repair of the vasculature (Scatena, Liaw, & Giachelli, 2007). Furthermore, Wada, McKee, Steitz, and Giachelli (1999) suggested that OPN may be a protective mechanism aimed at preventing calcification of vascular tissue. These functions of OPN along with its ability to increase the survival of endothelial cells (Wada et al., 1999) may suggest a protective role of OPN for the microvascular system.

Alternatively, it is possible that increased OPN concentrations could be a marker of pathogenic processes involved in the development of neuropathy (e.g., inflammation). Increased plasma levels of OPN have been shown in various diseases characterized by chronic inflammation (e.g., obesity) (Gomez-Ambrosi et al., 2007; Scatena et al., 2007). OPN is widely distributed in different human tissue, is localized in and around inflammatory cells, and often acts through regulating the inflammatory response (Scatena et al., 2007). Thus it is possible that as an inflammatory mediator, the chronic release of OPN could be toxic potentially leading to the dysfunction and degeneration of neurons (Brown, 2012). The cross-sectional nature of this study does not, however, allow for the determination of the role of OPN and its association with cardiovascular autonomic function. Furthermore, the diverse physiological functions of OPN may be the result of OPN’s structure, interaction with various receptors, and different isoforms.

We also investigated a potential association of OPG levels and autonomic function. Previously, elevated circulating levels of OPG have been reported in T2DM, particularly in the presence of microvascular complications (Knudsen et al., 2003), with several studies (Nybo et al., 2010; Tavintharan et al., 2014; Terekeci et al., 2009), but not all (Bourron et al., 2014), having shown an association between increased levels of OPG and peripheral neuropathy. The mechanism of this association was not clear. While OPG showed a significant bivariate association with MCR, our results did not show an association of OPG and cardiovascular autonomic function when OPG along with OPN was available as a potential independent variable in the linear regression models. Thus, even though OPN and OPG are two bone metabolism biomarkers, they appear to be distinct regulators and differ in their chemical structure and in their role of regulating various cell types.

There are some potential limitations of this study that deserve mention. Glycemic control was assessed by a single HbA1c and therefore is only reflective of short-term glycemic control. Although HbA1c was not selected in the regression models as an independent determinant, long term hyperglycemia affects nerve function and hyperglycemia has been shown to upregulate OPN (Mazzali et al., 2002). Some participants may have been using medications that could have influenced autonomic function and/or circulating bone metabolism biomarkers. Inclusion of a dichotomous variable in the linear regression models to indicate the use/no use of medications used to treat peripheral neuropathy did not affect the results. It should be noted also that there were no dose changes 2 months prior to enrollment for medications (e.g., antidiabetes).

In summary, OPN is associated with reduced parasympathetic nerve function particularly in younger persons with T2DM. There is a need for further studies to determine if OPN is neuroprotective, a biomarker of the pathogenic process of cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction, or an uninvolved bystander.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Clinical Research Committee, Department of Medicine, Christiana Care Health System, Newark, DE, USA.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Drs. Maser, Lenhard, Pohlig, and Balagopal declare that he/she does not have a personal or financial conflict of interest in the subject matter of this manuscript.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bourron O, Aubert CE, Liabeuf S, Cluzel P, Lajat-Kiss F, Dadon M, … Hartemann A. Below-knee arterial calcification in type 2 diabetes: Association with receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand, osteoprotegerin, and neuropathy. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2014;99:4250–4258. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A. Osteopontin: A key link between immunity, inflammation and the central nervous system. Translational Neuroscience. 2012;3:288–293. doi: 10.2478/s13380-012-0028-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitropoulos G, Tahrani AA, Stevens MJ. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus. World Journal of Diabetes. 2014;5:17–39. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekshyyan O, Aw TY. Apoptosis: A key in neurodegenerative disorders. Current Neurovascular Research. 2004;1:355–371. doi: 10.2174/1567202043362018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Ambrosi J, Catalan V, Ramirez B, Rodriguez A, Colina I, Silva C, … Fruhbeck G. Plasma osteopontin levels and expression in adipose tissue are increased in obesity. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;92:3719–3727. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzel S, Seven A, Kocaoglu A, Ilk B, Guzel EC, Saracoglu GV, Celebi A. Osteoprotegerin, leptin and IL-6: Association with silent myocardial ischemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes & Vascular Disease Research. 2013;10:25–31. doi: 10.1177/1479164112440815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jander S, Bussini S, Neuen-Jacob E, Bosse F, Menge T, Muller HW, Stoll G. Osteopontin: A novel axon-regulated Schwann cell gene. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2002;67:156–166. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen ST, Foss CH, Poulsen PL, Andersen NH, Mogensen CE, Rasmussen LM. Increased plasma concentrations of osteoprotegerin in type 2 diabetic patients with microvascular complications. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2003;149:39–42. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1490039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser RE, Lenhard MJ. Effect of treatment with losartan on cardiovascular autonomic and large sensory nerve fiber function in individuals with diabetes mellitus: A 1-year randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 2003;17:286–291. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(02)00205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser RE, Lenhard MJ, Pohlig RT. Vitamin D insufficiency is associated with reduced parasympathetic nerve fiber function in type 2 diabetes. Endocrine Practice. 2015a;21:174–181. doi: 10.4158/EP14332.OR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser RE, Lenhard MJ, Sneider MB, Pohlig RT. Osteoprotegerin is a better serum biomarker of coronary artery calcification than osteocalcin in type 2 diabetes. Endocrine Practice. 2015b;21:14–22. doi: 10.4158/EP14229.OR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzali M, Kipari T, Ophascharoensuk V, Wesson JA, Johnson R, Hughes J. Osteopontin—A molecule for all seasons. QJM. 2002;95:3–13. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/95.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller R, Stevens SL, Minami M, Cameron JA, King S, Rosenzweig H, … Stenzel-Poore MP. Neuroprotection by osteopontin in stroke. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2005;25:217–225. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nybo M, Poulsen MK, Grauslund J, Henriksen JE, Rasmussen LM. Plasma osteoprotegerin concentrations in peripheral sensory neuropathy in type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetic Medicine. 2010;27:289–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.02940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scatena M, Liaw L, Giachelli CM. Osteopontin: A multifunctional molecule regulating chronic inflammation and vascular disease. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2007;27:2302–2309. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.144824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumer MP, Joyner SA, Pfeifer MA. Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy testing in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 1998;11:227–231. [Google Scholar]

- Stepien E, Wypasek E, Stopyra K, Konieczynska M, Przybylo M, Pasowicz M. Increased levels of bone remodeling biomarkers (osteoprotegerin and osteopontin) in hypertensive individuals. Clinical Biochemistry. 2011;44:826–831. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Sato T, Ichikawa H. Osteocalcin- and osteopontin-containing neurons in the rat hind brain. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 2012;32:1265–1273. doi: 10.1007/s10571-012-9851-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sytze Van Dam P, Cotter MA, Bravenboer B, Cameron NE. Pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy: Focus on neurovascular mechanisms. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2013;719:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavintharan S, Pek LT, Liu JJ, Ng XW, Yeoh LY, Lim SC, Sum CF. Osteoprotegerin is independently associated with metabolic syndrome and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes & Vascular Disease Research. 2014;2014:1–4. doi: 10.1177/1479164114539712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terekeci HM, Senol MG, Top C, Sahan B, Celik S, Sayan O, … Ozata M. Plasma osteoprotegerin concentrations in type 2 diabetic patients and its association with neuropathy. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes. 2009;117:119–123. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1085425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tousoulis D, Siasos G, Maniatis K, Oikonomou E, Kioufis S, Zaromitidou M, … Stenfanadis C. Serum osteoprotegerin and osteopontin levels are associated with arterial stiffness and the presence and severity of coronary artery disease. International Journal of Cardiology. 2013;167:1924–1928. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinik AI, Erbas T, Casellini CM. Diabetic cardiac autonomic neuropathy, inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Journal of Diabetes Investigation. 2013;4:4–18. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinik AI, Strotmeyer ES, Nakave AA, Patel CV. Diabetic neuropathy in older adults. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2008;24:407–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T, McKee MD, Steitz S, Giachelli CM. Calcification of vascular smooth muscle cell cultures: Inhibition by osteopontin. Circulation Research. 1999;84:166–178. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MC, Mi R, Connor E, Reed N, Vyas A, Alspalter M, … Hoke A. Novel roles for osteopontin and clusterin in peripheral motor and sensory axon regeneration. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34:1689–1700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3822-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]