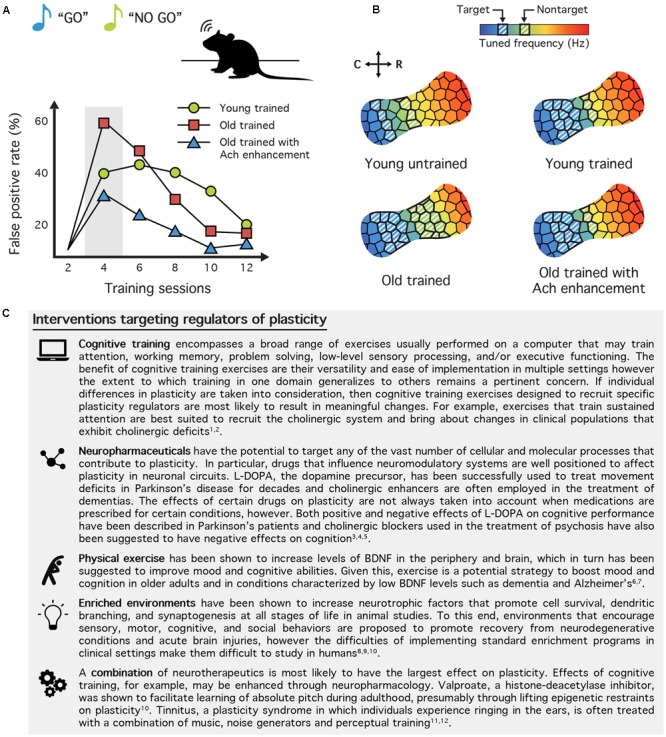

FIGURE 2.

Neurotherapeutic interventions targeting regulators of plasticity. (A) Cholinergic enhancement paired with training reduces the probability of false positives (FP) in aged rats. Young adult and old (>24-month-old) rats were trained on a “Go (target frequency)/No-Go (non-target frequency)” auditory perceptual learning task. The FP rate can be used as an indicator of distractibility, and aged humans and rodents tend to have particularly high FP rates during early stages of training. When aged rats were given the cholinesterase inhibitor rivastigmine before each training session their FP rate was halved. This suggests that boosting the cholinergic system can enhance perception and behavioral performance in the elderly by reducing distractibility. (B) The tonotopic map of trained aged rats resembles young rats when training is paired with cholinergic enhancement. Compared to a naive, young adult rat (top left), the map of a trained rat (top right) will have a greater proportion of sites tuned to the target stimulus frequency and a smaller proportion tuned to the non-target frequency. This differential representation is believed to help the rat assign more importance to the target tone and ignore the non-target. In old rats (bottom left), however, training results in an equal enlargement of both the target and non-target frequency regions. While these rats are capable of learning the discrimination task, this alternative learning mechanism may result in their elevated FP rate. Indeed, old rats trained with rivastigmine (bottom right), which exhibit less distractibility exhibit map plasticity like young adult rats (A,B modified from Voss et al., 2016). (C) Table of neurotherapeutic interventions aimed at mechanisms of plasticity. By targeting the various regulators of plasticity, the goal of neurotherapeutics is to utilize the brain’s innate capacity to change to improve learning, memory, and recovery from neurological injury or disease. This brief selection demonstrates a broad range of behavioral, pharmaceutical, and environmental interventions either currently available or under exploration today. References: (1) Vinogradov et al., 2012; (2) Cramer et al., 2011; (3) Cools, 2006; (4) Suraweera et al., 2015; (5) Grinevich et al., 2009; (6) Coelho et al., 2013; (7) Szuhany et al., 2015; (8) Mora et al., 2007; (9) Nithianantharajah and Hannan, 2006; (10) Alwis and Rajan, 2014; (11) Gervain et al., 2013; (12) Zenner et al., 2017.