Abstract

We usually associate triage with the Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment method, but much of its origin is still unknown. Therefore, French studies and the origin of triage shown in domestic and foreign published works have been investigated and its significance reaffirmed. The etymology of the word “triage” means “to break into three pieces.” It was suggested by a literature review that the rise of Napoleon led to military tactical changes, and that the prototype of triage arose from the experience gained in the difficult campaign in Egypt and Syria. Subsequently, triage was refined by Napoleon's military surgeon, D. J. Larrey, who created the ambulance transport system. Although there is a clash between the ruthless and philanthropic aspects of triage, triage is in accordance with the primary purpose of evacuation or treatment. We should choose the triage method that is consistent with the purpose of each disaster situation.

Keywords: Ambulance, evacuation, Napoleon, Syria campaign

Introduction

The Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START)1 method was developed by Hoag Hospital and the Newport Beach Fire Department in California in the 1980s. Generally, it is understood in Japan that triàge was developed by the army surgeon Larrey during the Napoleonic era2, 3. However, the systematic development of triàge is not clear from historical records. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the historical development of triàge and consider the meaning of the concept in Japan from the records relating to two army surgeons.

Etymology of “triàge”

Many documents have reported that the medical term “triàge,” as used in Japan, derives from the sorting of coffee beans.4, 5 However, Holler and others reported that “triàge” originated with the concept of thinning out inferior wool products in Britain in 1727. It has been reported that the term “triàge” was used for the sorting of coffee beans in Britain in around 1830.6 It would appear, however, that the medical use of the term “triàge” in the battlefield derives not from the classification of coffee beans but from the earlier sorting in the wool industry.

The etymology of “triàge” is French. Studies have shown that trier, which is the verb form of triàge, dates back to the 12th‐century Gallo‐Romance term triàre. That word can be divided into trià and eur, which mean, respectively, “three” and “crushing.” The French word triàge means “to thin out” in Japanese and “to categorize” in English. “Thinning out” signifies the removal of damaged items toward improving the overall quality. The original meaning of “triàge” is closer to the notion of thinning out than to categorization. However, the concept of sorting could also apply to such French terms as presélection, sélection, and choix.

“Triàge” may have come to be applied in the area of disaster medicine because it combines the meaning of both dividing into three and thinning out. With respect to military medical care, Larrey categorized triàge into three phases7. In a comparable fashion, French military doctors in World War I and Japanese military physicians in World War II divided sick or wounded soldiers into three categories according to the severity of their illnesses or wounds. Similarly, the Sort, Assess, Life‐Saving Interventions, Treatment and/or Transport (SALT) triàge, which is a modern American triàge method for dealing with disasters and mass casualties, involves an initial classification of cases into three categories.8

Military medical care before development of triàge

It is believed that during the monarchy in France until the 18th century, condottieri (mercenary leaders) offered their services to the crown as well as other powers. Condottieri fought with regular troops, were highly skilled in tactics, and played an effective role in battles. The condottieri organized their own troops and are said to have defrauded nobles by exaggerating the numbers of mercenary solders they were able to field. Before a battle, the condottieri on both sides came to an agreement and continued to work in that way throughout long wars. However, following the French Revolution of 1789 and the creation of its First Republic, many French conscripted soldiers, who came from poor backgrounds, wished to return to their own country because of tax incentives. During those times, the many military campaigns and fierce battles led to large numbers of dead or wounded soldiers.

The tactics of Napoléon Bonaparte were characterized by methods that aimed to hunt and destroy any remaining enemy forces with the use of cavalry. Napoléon was indeed able to secure a series of victories by means of such tactics. That resulted in many wounded foot soldiers (not officers) being stranded on the battlefield at great distance from the main body of troops. Thus, large numbers of wounded soldiers were left to die without being able to receive emergency medical care.9 Subsequently, great numbers of people from poor backgrounds were drafted to serve in armies and fight as soldiers. As a consequence, medical care for large numbers of wounded soldiers didn't develop, and triàge didn't come into being.

Army surgeons Percy and Larrey

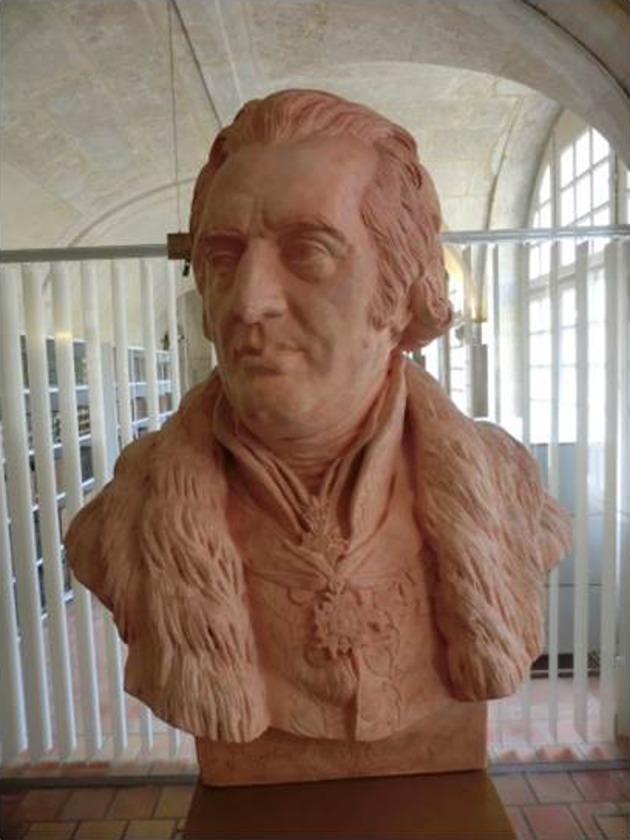

Two military surgeons played a key role in developing triàge on the battlefield. Pierre‐François Percy (1754–1825) served in military campaigns from the monarchy era in France (Fig. 1). He was a university professor, an established figure in medicine, and an authority in Parisian medical society10. Percy developed an ambulance system, which used a four‐wheeled vehicle to convey surgeons and their equipment to the battlefield. He also organized medical care teams in 1813. This system was, however, used for treating army officers, not foot soldiers. Percy was the first person to receive the Legion of Honor, which was created by Napoléon, and Percy was trusted by the French leader (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Pierre Francois Baron de Percy (1754–1825). (Hôpital Militaire du Val‐de‐Grâce)

Table 1.

Chronological table on triage according to published scientific work

| A.D. | History of Triage | History of Napoleon |

|---|---|---|

| 1048 | Knights of Saint John | |

| 1754 | Birth of P. F. B. Percy | |

| 1766 | Birth of D. J. Larrey | |

| 1769 | Birth of Napoleon | |

| 1789 | Larrey participated in a medical team for the revolutionaries | The French Revolution |

| 1792 | Larrey participated on the Rhine Front | Rhine Front |

| Larrey experienced the horrible battlefield, realizes the high mortality | Napoleon made captain | |

| 1793 | Tests the flying ambulance | Battle of Metz |

| 1794 | The ambulance system was approved by the French Army. Larrey makes his first acquaintance with Napoleon | |

| 1795 | The ambulance system was unapproved by Napoleon | |

| 1796 | Horse‐drawn transport aid, which first took place on the Italian Front | Napoleon becomes Commander‐in‐Chief of the Army in Italy |

| 1797 | Larrey organized ambulance units | Italian Front |

| 1798 | French Expedition to Egypt and Syria | |

| Conscription under the Jourdan‐Delbrel Law | ||

| 1799 | P. F. B. Percy invented an operation wagon | |

| Defeated for the first time in the Siege of Acre (Akko) | ||

| Napoleon returned to Paris from Egypt | ||

| 1800 | Napoleon crossed the Alps | |

| 1801 | Triage at the Hotel‐Dieu of Paris | |

| 1802 | Peace of Amiens | |

| 1804 | Napoleon became emperor | |

| 1805 | Battle of Trafalgar | |

| Battle of the Three Emperors at Austerlitz | ||

| 1806 | Triage was implemented during the Battle of Jena | Battle of Jena |

| 1807 | Many field hospitals were established around the battlefield by Larrey | |

| Battle of Eylau | ||

| Promulgation of the Edict of Milan | ||

| 1808 | The word “triage” appeared for the first time in Percy's diary | |

| 1809 | Percy organized an army medical team of mobile sanitation | |

| Franco‐Austrian War | ||

| Battle of Aspern | ||

| 1812 | The triage method was refined by Larrey. The patients were divided into categories, serious ones being treated first. | Anglo‐American War of 1812 |

| Declared war on Russia | ||

| Withdrawal from Moscow | ||

| 1813 | Percy became involved with Larrey and created the stretcher soldiers, who took the wounded off the battlefield. | |

| 1814 | First Restoration | |

| Abdication of Napoleon | ||

| Congress of Vienna | ||

| 1815 | Defeated in the Battle of Waterloo | |

| 1821 | Napoleon died on Saint Helena | |

| 1825 | Death of Percy (Paris) | |

| 1840 | Napoleon was reburied in Paris | |

| 1842 | Death of Larrey (Lyon), who was buried next to Napoleon I |

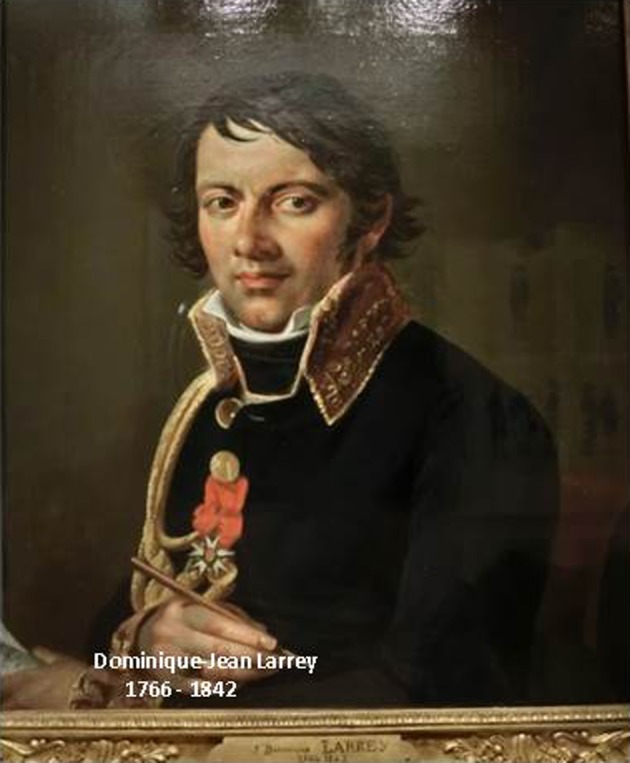

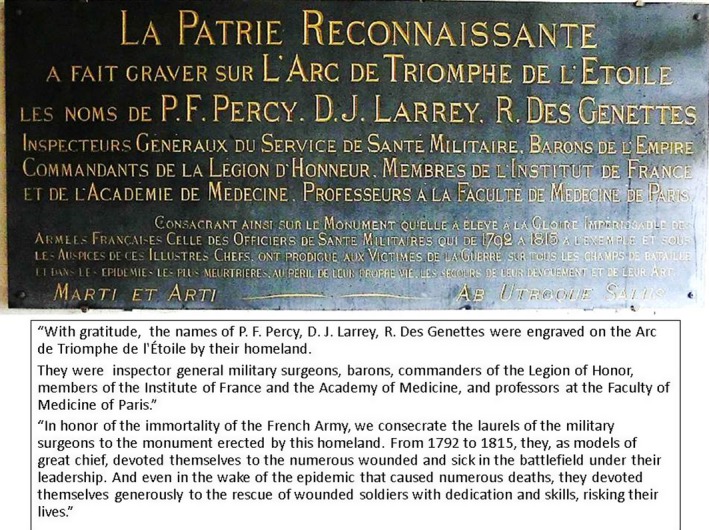

The other army surgeon, Dominique Jean Larrey (1766–1842), was 12 years younger than Percy, and Larrey was deeply involved in the development of triàge. Larrey attended theological college at the age of 13 and possessed a strong philanthropic disposition (Fig. 2). This philanthropic approach to triàge has persisted to the present day. Following the French Revolution, Larrey gradually came to occupy a position of leadership in the medical team of the French military in 1798. As a result of his efforts and the dramatic reduction in deaths on the battlefield, Larrey also received the Legion of Honor and a commemorative plate was engraved on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, which praised the man (Fig. 3). Napoléon was greatly impressed with Larrey's ability in reducing battlefield mortality.

Figure 2.

Dominique‐Jean Larrey (1766–1842). (Hôpital Militaire du Val‐de‐Grâce)

Figure 3.

Gratitude plate engraved on the Arc de Triomphe (Paris, France). (Hôpital Militaire du Val‐de‐Grâce)

Development of triàge

The concept of triàge was not described in a manual of French military medical care until, at the earliest, 1792.11 Triàge would appear to have been developed during the period 1792–1801 because there is a record of triàge having been formally adopted by the French military in 1801.7, 12, 13, 14 There were no wars or events concerning the development of triàge between 1792 and 1797 (Table 1). From historical documents and my own research in the French army medical care museum, Le Musée du Service de Santé des Armées au Val‐de‐Grâce, we may assume that the first type of triàge was developed in the 4 years between 1797 and 1801. This original triàge method is described below as Napoleonic triàge to distinguish it from other triàge methods.15

During that 4‐year period, Napoléon conducted military expeditions in Egypt and Syria. A blockade by the British fleet stopped Napoléon's army receiving supplies and additional troops from France. He was obliged to make a difficult push to Syria with little food and under poor sanitary conditions.16 The French military fought a series of battles in Syria and laid siege to Akko (Siège de Saint‐Jean‐d'Acre). However, one‐fifth of Napoléon's army died as a result of bad weather, poor sanitation, and plague.16 At the end of the campaign, around one‐third of the French troops had died in battle or through illness.17 For the first time, Napoléon was obliged to retreat. At that time, it may be supposed that he lost many wounded soldiers who had to return to the battlefield. The concept of primary triàge came about during that campaign. However, with Napoleonic triàge, the priority was given to treating sick and wounded soldiers who were able to fight again on the battlefield. Treatment was thus given from a military perspective – not from the point of view of prioritizing the saving of life, as in modern medicine. It should be observed that no documents about the medical care at this time have survived, and the above is an assumption.

It is not clear who originally proposed the concept of Napoleonic triàge. In all likelihood, it was not Larrey. Three reasons support this conclusion: (i) during that 4‐year period, Larrey had yet to gain the trust of Napoléon, (ii) the concept of triàge proposed by Larrey differed from the heartless Napoleonic triàge, (iii) Larrey had opposed Napoléon regarding the type of medical care provided on the battlefield during those 4 years. In addition, studies produced in Britain, the USA, and Japan have determined that Larrey developed the concept of first triàge, not Napoleonic triàge.18, 19, 20, 21, 22

In contrast, Percy at that time held the position of surgeon general and was responsible for medical care on the battlefield. Percy is a more likely candidate as the person who developed Napoleonic triàge. The word “triàge” does not appear in the diary of Larrey.13, 14 However, the term does appear in Percy's diary with respect to treating wounded soldiers.23 The use of triàge as a medical term was recorded during the American Civil War (1861–65). It may be that the term was applied there after being introduced from Britain, where the wool industry was being developed.19

The achievement of the army surgeons Percy and Larrey was in modernizing Napoleonic triàge to help save lives.7, 12, 19

Use of triàge

In the Battle of Jena in 1806, the French army used the triàge system developed by Larrey (Table 1). The system involved categorization into three grades based on the severity of the wounds irrespective of the soldier's rank: dangerously wounded, less dangerously wounded, and slightly wounded. If the grading involved four categories, it would be difficult to separate grades II and III. It is necessary that grades II and III not be separated with respect to evacuating soldiers from dangerous areas.

Historical meaning of triàge

An important point with triàge relates to whether it should apply to evacuation from a dangerous area or in selection – taking effective medical care in disaster. Although they are both used in disaster medicine, the two approaches to triàge methods are dissimilar. Triàge for evacuation should be used to reduce the number of injury classifications among injured people in a dangerous area. When triàge is used to provide effective medical care following a disaster, the number of grades used in the classification should be increased to minimize the risk for patients.

Conclusion

We may conclude from various documents that it became necessary to categorize wounded soldiers on the battlefield into three types by means of triàge. Wounded soldiers had to be evacuated so that they would spend the least amount of time in dangerous areas. Triàge has come to have three different meanings: (i) Napoleonic triàge on the battlefield, (ii) triàge to provide effective medical care following a disaster, (iii) triàge as commonly applied in the emergency room.

Historically, battlefield mortality decreased drastically through Larrey's novel idea of quickly transporting wounded soldiers to field hospitals. His approach was of simply categorizing the wounded into three grades using triàge until transport and evacuation. Triàge is currently used at many hospitals in the context of disaster training. However, it is necessary with triàge to recognize that it is at present only one of the assessment processes in advance of evacuation or acceptance of patients by hospitals. Generally, classification exists for a particular purpose, and classification should be undertaken in the context of that purpose. Accordingly, classifications change with time. It is important, however, to understand the origins of the term “triàge.” Disaster medicine is based on the creation of a study system after making an academic investigation of the historical background.

Disclosure

Funding: No academic funding is used for this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials: All data is accrued from review of the literature.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable.

Authorship: All authors contribute to this study.

This article is based on a study first reported in Journal of Japanese Association for Acute Medicine 2016; 27: 139–73.

Funding Information

No funding information provided.

References

- 1. Benson M, Koenig KL, Schultz CH. Disaster Triage: START, then SAVE–A new method of dynamic triage for victims of a catastrophic event. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 1996; 11: 117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Henmi H. Triage of the emergency and disaster area. Sodo corp. 2001. p2. (In Japanese)

- 3. Ogli K, Yoshioka T, Sugimoto H. The spot activity to MIMMS casualty disaster for medical care and medical support, the 2nd. Nagaishoten. 2010, p107–20. (In Japanese)

- 4. Yamamoto Y, Ukai S. Triage significance and practice. Sodo corp. 1999; 6–8. (In Japanese)

- 5. Watanabe T, Minami Y, Yamamoto A. A disaster nursing learning text. Jpn. Nurs. Assoc. Publ. Soc. 2007; 60–5. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holler J Jr. Battlefield Medicine. Carbondale, Illinois, USA: Southern Illinois University Press; 2011; p156. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Skandalakis PN, Lainas P, Zoras O et al “To Afford the Wounded Speedy Assistance”: Dominique Jean Larrey and Napoleon. World J. Surg. 2006; 30: 1392–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cone DC, Serra J, Burns K et al Pilot test of the SALT mass casualty triage system. Prehosp. Emerg. Care. 2009; 13: 536–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reinhardt B, Kikuchi Y. Cultural history of the German hired soldier. Shin Hyoron. 2002; p233–58. (In Japanese)

- 10. Cazala`a JB, Carli P. Larrey and Percy—A tale of two Barons David Baker. Resuscitation. 2005; 66: 259–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Percy PF. Manuel du chirurgien‐d'armee ou instruction de chirurge‐militaire: Chez Germer Baillière. Libraire. 1830.

- 12. Iserson KV, Moskop JC. Triage in Medicine, Part I: Concept, history, and types. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2007; 49: 275–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blagg CR. Triage: Napoleon to the present day. J. Nephrol. 2004; 17: 629–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larrey DJ. Translated by Richard Willmott; Memoirs of Military Surgery, And Campaigns of the French Armies, on the Rhine, In Corsica, Catalonia, Egypt, and Syria: in Saxony, Paxony, Prussia, Poland, Spain, and Austria (Vol.1). Joseph Cushing. Baltimore: 1814. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Odate T. Dilemma between military and the medical – about the history of triage–. The military history society of Japan. 2013; 49: 60–80. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wood MM. Dominique‐Jean Larrey, chief surgeon of the French Army with Napoleon in Egypt: Notes and observations on Larrey's Medical Memoirs based on the Egyptian campaign Mary Mendenhall Wood. Can. Bull. Med. Hist. 2008; 25: 515–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuhnke W, Kuhnke L. French observations of disease and drug use in late eighteenth‐century cairo. J. Hist. Med. 1984; 1: 121–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Advanced life Support Group , Ogli K. Medical support at the time of the casualty disaster. Herusu‐Shuppan. 1995, p107. (In Japanese)

- 19. Lorenzo RAD, Porter R. Tactical emergency care military and operational out‐of‐Hospital medicine. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, USA: Prentice‐Hall Inc., 1999; 230–47. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kennedy K, Aghababian RV, Gans L et al Triage: Techniques and applications in decisionmaking. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1996; 28: 136–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Henrich C. Evaluating the legacy of civil war medicine: Amputations, anesthesia, and administration. [cited 16 Jun 2015]. http://www.schoolinfosystem.org/pdf/2010/01/lastcivilwarmedicinew09.pdf p217.

- 22. Remba SJ, Varon J, Rivera A et al Dominique‐Jean Larrey: The effects of therapeutic hypothermia and the first ambulance. Resuscitation. 2010; 81: 268–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Percy PF. Journal Des Campagnes Du Baron Percy, Chirurgien En Chef De La Grande Armee. Émile Longin. 1904, Plon‐Nourrit.