Abstract

Objective

Surgical outcomes of thyroid cancer patients are improved with high-volume surgeons. However, age disparities in referral to specialist surgical centers still exist. The factors that influence decision-making regarding referral of older thyroid cancer patients to high-volume surgeons remain unknown.

Methods

We surveyed members of the Endocrine Society, American College of Physicians and American Academy of Family Practice.

Results

Overall, 269 physicians completed the survey. Patient preference (68%), transportation barriers (63%) and confidence in local surgeon (54%) were the most cited factors decreasing likelihood of referral to a high-volume surgeon. In clinical scenarios, referral rates to a high-volume surgeon were similar for patients aged 40 and 65 with a 1 cm thyroid nodule diagnostic of thyroid cancer (N=137, 54%; N=132, 52% respectively) as for an 85-year-old with a 4 cm nodule (N=148, 59%). When comorbidities were introduced, more physicians (N=186, 74%) would refer a 65-year-old with a 4 cm thyroid nodule and comorbidities, compared to an 85-year-old with the same nodule size without comorbidities. In multivariable analysis, treating >10 thyroid cancer patients/year (p <0.001, p 0.005) and endocrinology specialty (p 0.003, p 0.003) were associated with referral to a high-volume surgeon for a 65-year-old with comorbidities and an 85-year-old without comorbidities.

Conclusions

Understanding surgical referral patterns of older thyroid cancer patients is vital in identifying obstacles in the referral process. We found that patient factors including comorbidities, and physician factors including specialty and patient volume, influence these patterns. This is the first step towards developing targeted interventions for these patients.

Key words for indexing: thyroid cancer, surgery, referral

BACKGROUND

The incidence of thyroid cancer is rising, with thyroid cancer now the eighth most common cancer in the United States.(1–5) Although typically a cancer with a favorable prognosis, the aggressiveness of thyroid cancer increases with age.(6, 7) There is also a recognized association between older age and worse outcomes.(8) Studies have shown that surgical outcomes of thyroid cancer patients, and older patients specifically, are improved with a high-volume thyroid surgeon.(9–16) However, current data show that older patients with thyroid cancer are less likely to receive guideline concordant care.(17) Additionally, older age and Medicare insurance were found to be independently associated with less aggressive management of patients with high-risk thyroid cancer.(18)

Even though older patients with thyroid cancer would benefit from referral to high-volume thyroid surgeons, age disparities in referral to a specialist surgical center exist.(19) The factors that influence decision making regarding referral of older thyroid cancer patients to a high-volume thyroid surgeon remain unclear and previously unexplored. Whether these decisions vary by type of provider is also not known. Determination of these factors would facilitate improving quality of care and developing targeted interventions in this growing population of thyroid cancer patients.

The objective of our study was to delineate the factors that influence decision making regarding referral of older thyroid cancer patients (age ≥65 years) to high-volume thyroid surgeons. We conducted a nationwide physician survey targeting endocrinologists, internists and family practitioners.

METHODS

Study Population

Members of the American College of Physicians, the American Academy of Family Practice and the Endocrine Society were randomly selected and surveyed. The modified Dillman survey method was used to enhance survey response rates.(20) This three-wave method of survey administration comprises of (i) an initial mailing of an introductory letter, the survey instrument, a postage-paid return envelope, and a small monetary gift; (ii) a postcard reminder 3 weeks later; and (iii) a second survey with a postage-paid return envelope to all non-respondents 3 weeks later. Follow-up telephone encounters were also conducted with non-respondents. Data from the returned surveys were de-identified, entered into a Research Electronic Data Capture (i.e., REDCap) database and verified by the double entry method to ensure <1% error (21). The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Survey Design and Measures

The instrument was designed by a diverse group of physicians and survey methodologists. It was subsequently piloted in a multidisciplinary group of providers at the University of Michigan prior to survey administration. The survey instrument included both questions and clinical vignettes. Responses regarding physician specialty, practice setting, years in practice and thyroid cancer patient volume were obtained from the survey questions (independent variables). Information on factors influencing likelihood of referral of older thyroid cancer patients (age ≥65 years) to a high-volume surgeon (defined as performing >100 thyroid surgeries per year) was also obtained. Factors listed included insurance restrictions, high risk for complications, patient immobility, patient’s inability to perform basic activities (e.g. eating, bathing), patient’s inability to perform more complex activities (e.g. shopping, managing finances), lack of patient’s social support system, transportation barriers, patient preference and confidence in local surgeon.

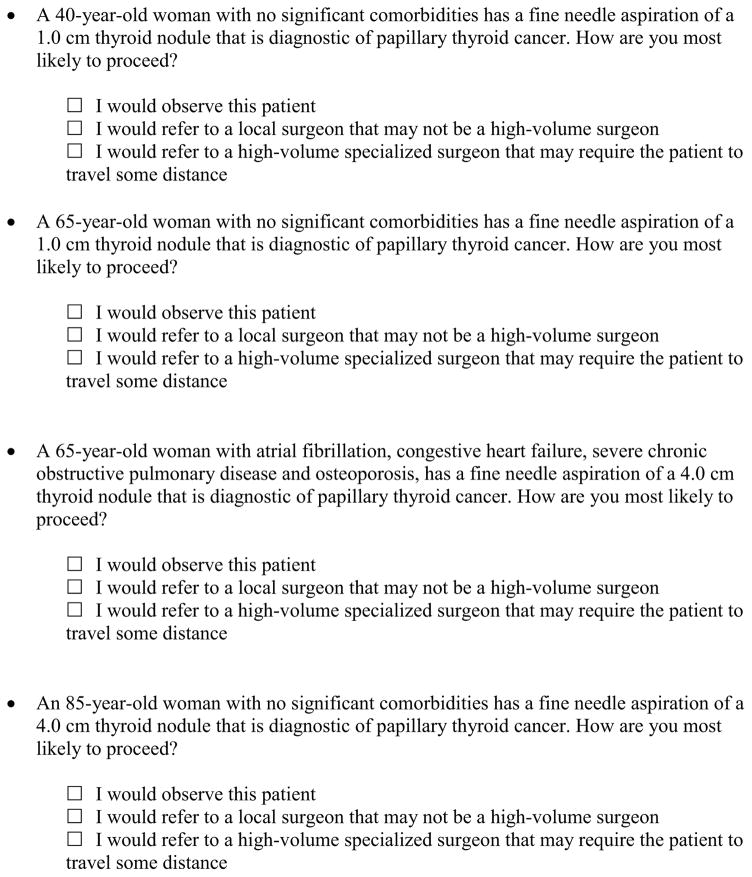

Four thyroid cancer vignettes were included in the survey instrument: a 40-year-old patient without comorbidities with a 1.0 cm thyroid nodule diagnostic of papillary thyroid cancer, a 65-year-old patient without comorbidities with a 1.0 cm thyroid nodule diagnostic of papillary thyroid cancer, a 65-year-old patient with comorbidities (atrial fibrillation, osteoporosis, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and congestive heart failure) with a 4.0 cm thyroid nodule diagnostic of papillary thyroid cancer, and an 85-year-old patient without comorbidities with a 4.0 cm thyroid nodule diagnostic of papillary thyroid cancer. Surveyed physicians were asked to choose one of the following answers: observe the patient, refer to a local surgeon that may not be a high-volume surgeon, or refer to a high-volume specialized surgeon that may require the patient to travel some distance (Figure 1). The dependent variable was collapsed into a binary variable: refer to a high-volume surgeon versus not refer.

Figure 1.

Selected clinical vignettes from the physician survey are shown.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate analyses of physician characteristics associated with referral of older thyroid cancer patients to a high-volume surgeon were performed using chi-square tests for all the clinical vignettes. Multivariable analysis was performed using logistic regression to evaluate the independent effect of physician characteristics on referral.

All statistical tests were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22. A P value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Out of the 762 response-eligible physicians surveyed who treated thyroid cancer patients, 269 completed the survey. Physician characteristics are shown in Table 1. When presented with clinical scenarios, referral rates to a high-volume surgeon were similar for patients aged 40 and 65 years old with a 1 cm thyroid nodule diagnostic of thyroid cancer (N=137, 54% and N=132, 52%, respectively) as for an 85-year-old with a 4 cm nodule (N=148, 59%). When comorbidities were introduced (atrial fibrillation, osteoporosis, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), more physicians (N=186, 74%) would refer a 65-year-old with a 4 cm thyroid nodule diagnostic of thyroid cancer and comorbidities to a high-volume surgeon, compared to an 85-year-old with the same nodule size without comorbidities.

TABLE 1.

PHYSICIAN CHARACTERISTICSa

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 164 (62) |

| Female | 101 (38) |

| Race | |

| White | 197 (62) |

| Asian | 50 (16) |

| Other | 16 (5) |

| Years in practice | |

| 0–5 years | 36 (14) |

| 6–10 years | 37 (14) |

| 11–20 years | 69 (26) |

| >20 years | 124 (47) |

| Specialty | |

| Endocrinology | 113 (41) |

| Family Practice | 73 (27) |

| Internal Medicine | 70 (26) |

| Other | 18 (7) |

| Primary practice setting | |

| Private practice | 140 (52) |

| Academic tertiary care center | 35 (13) |

| Community-based academic affiliate | 57 (21) |

| Other | 36 (13) |

| Number of thyroid cancer patients physician provided care to in the last year | |

| 0–10 | 184 (69) |

| >10 | 82 (31) |

Missing data not included

The results of the univariate and multivariable analyses of physician characteristics associated with referral to a high-volume surgeon for the clinical vignettes describing a 65-year-old thyroid cancer patient with comorbidities and an 85-year-old thyroid cancer patient without comorbidities are shown in Tables 2 and 3 respectively. In univariate analyses, both for a 65-year-old patient with comorbidities and for an 85-year-old patient without comorbidities with the same nodule size, endocrinologists (p<0.001; p<0.001 respectively), physicians in academic settings (p 0.033; p 0.028) and physicians treating >10 thyroid cancer patients per year (p 0.013; p 0.001) were more likely to refer to a high-volume surgeon. Physicians with fewer years in practice (p 0.031) were also more likely to refer an 85-year-old patient with a larger thyroid nodule but without comorbidities to a high-volume surgeon. In multivariable logistic regression analysis, however, only endocrinology specialty (p 0.003; p 0.003) and thyroid cancer patient volume over 10 per year (p <0.001, p 0.005) were statistically associated with referral to a high-volume surgeon for both above analyzed clinical scenarios. Treating more than 10 thyroid cancer patients per year was also statistically associated with referral to a high-volume surgeon for a 40-year-old and a 65-year-old thyroid cancer patient with small thyroid nodules (1 cm) and without comorbidities (p 0.013, p 0.015).

TABLE 2.

UNIVARIATE AND MULTIVARIABLE ANALYSES OF PHYSICIAN CHARACTERISTICS ASSOCIATED WITH REFERRAL TO A HIGH-VOLUME SURGEON (65-year-old female with atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, severe COPD and osteoporosis, has a fine needle aspiration of a 4.0 cm thyroid nodule that is diagnostic of papillary thyroid cancer)

| Physicians referring to a high-volume surgeon [(n (%)] | Univariate p value |

Multivariable p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialty | <0.001 | ||

| Endocrinology | 88 (73) | 0.003 | |

| Internal Medicine | 45 (47) | 0.109 | |

| Family Practice | 42 (32) | Ref | |

| Other | 11 (29) | 0.760 | |

| Practice setting | 0.033 | 0.638 | |

| Private practice | 98 (52) | ||

| Community-based affiliate | 24 (46) | ||

| Academic tertiary care center | 41 (53) | ||

| Other | 22 (32) | ||

| Number of thyroid cancer patients seen in 1 year | 0.013 | 0.005 | |

| 0–10 | 118 (64) | ||

| >10 | 67 (82) | ||

| Years in practice | 0.260 | 0.935 | |

| 0–5 | 27 (59) | ||

| 6–10 | 26 (54) | ||

| 11–20 | 44 (43) | ||

| >20 | 88 (47) |

TABLE 3.

UNIVARIATE AND MULTIVARIABLE ANALYSES OF PHYSICIAN CHARACTERISTICS ASSOCIATED WITH REFERRAL TO A HIGH-VOLUME SURGEON (85-year-old female without significant comorbidities has a fine needle aspiration of a 4.0 cm thyroid nodule that is diagnostic of papillary thyroid cancer)

| Physicians referring to a high-volume surgeon [(n (%)] | Univariate p value |

Multivariable p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialty | <0.001 | ||

| Endocrinology | 76 (63) | 0.003 | |

| Internal Medicine | 31 (32) | 0.127 | |

| Family Practice | 31 (24) | Ref | |

| Other | 10 (26) | 0.443 | |

| Practice setting | 0.028 | 0.261 | |

| Private practice | 71 (38) | ||

| Community-based affiliate | 19 (37) | ||

| Academic tertiary care center | 39 (51) | ||

| Other | 18 (27) | ||

| Number of thyroid cancer patients seen in 1 year | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

| 0–10 | 88 (48) | ||

| >10 | 59 (72) | ||

| Years in practice | 0.031 | 0.266 | |

| 0–5 | 26 (57) | ||

| 6–10 | 21 (44) | ||

| 11–20 | 34 (33) | ||

| >20 | 66 (36) |

Figure 2 demonstrates the factors associated with decreased likelihood of referral of older thyroid cancer patients (age ≥65 years) to a high-volume surgeon. Patient preference (68%), transportation barriers (63%) and confidence of the referring doctor in local surgeon (54%) were the factors cited as most important in decreasing likelihood of referral. Less frequently quoted factors were insurance restrictions (30%), patient inability to perform basic (28%) or instrumental (21%) activities of daily living, lack of social support (27%) and patient immobility (26%). Being at high risk for complications was infrequently quoted as a reason not to refer an older patient to a high-volume surgeon for thyroid cancer surgery (3%).

Figure 2.

Factors cited by physicians as decreasing likelihood of referral of older adults (age ≥65 years) with thyroid cancer to a high-volume surgeon.

DISCUSSION

In this national survey of a diverse group of physicians who treat patients with thyroid cancer, we found that whereas close to three-fourths of physicians would refer an older patient with comorbidities and a large thyroid nodule diagnostic of thyroid cancer to a high-volume surgeon, just over half would refer an oldest old patient without comorbidities with the same nodule size. We also found that endocrinologists and physicians treating more than 10 thyroid cancer patients per year are more likely to refer older thyroid cancer patients with or without comorbidities to a high-volume thyroid surgeon. Patient preference, transportation barriers and confidence in local surgeon were the most commonly reported reasons to decrease likelihood of referral to a high-volume surgeon.

Total thyroidectomy with or without neck lymph node dissection, which may be followed by radioactive iodine ablation, is the standard of care for patients with differentiated thyroid cancer.(22) However, it was previously demonstrated that elderly patients with differentiated thyroid cancers receive less aggressive surgical and radioactive iodine treatment than younger patients, despite having more advanced disease and improved survival associated with treatment.(17) Successful surgery for thyroid cancer has been shown to not only increase the survival rate but also improve the quality of life of older patients.(23) It is generally perceived that the elderly may have increased operative risks because of the presence of increasing number of comorbidities, thus leading to a more conservative or non-operative approach to be adopted in these patients with thyroid cancer.(24–26) Older individuals with comorbidities are also at risk for functional disabilities, which can further impact cancer treatment strategies.(27) Additionally, several prior studies have shown that high surgeon volume is a significant predictor of improved outcomes following thyroidectomy, and has been associated with more completeness of initial operation (14, 15), shorter length of hospital stay, lower postoperative complication rates and lower costs.(9–14, 16) The lowest postoperative complication rates have been shown to be achieved by surgeons performing ≥100 operations annually (9, 28), but the threshold number of thyroid procedures that differentiates high-volume from low-volume surgeons varied across studies.(9, 28–31) Recently, a study has suggested a minimum threshold of 25 thyroid operations annually before detectable differences in outcomes may occur.(16) Despite these data, the majority of endocrine surgeries, including thyroidectomies, are performed by low-volume surgeons.(32)

Recognizing the patterns of surgical referral for older thyroid cancer patients and the factors influencing these patterns is vital in identifying obstacles in the referral process. Our team previously found that 44% of endocrinologists would refer a high-risk thyroid cancer patient to another facility for care, with 24% of them citing need for lateral neck dissection as the reason for referral.(33) However, not all surgery referrals come from endocrinologists, and the role of the patient’s age and presence of comorbidities in the decision-making process has not previously been elicited. In this current study, when focusing on older patients and surveying a multidisciplinary cohort of physicians, we found that the presence of comorbidities was appropriately associated with more referral to high-volume surgeons. It has been shown that comorbidity, regardless of age, may affect treatment choices, have prognostic significance and may increase complexity of care in cancer patients.(25, 34–36)

Our finding in multivariable analysis that primary care physicians are less likely to refer older thyroid cancer patients with or without comorbidities to a high-volume surgeon, as compared to endocrinologists, may suggest a gap in knowledge. In our experience, primary care physicians are typically the ones who initiate the first surgical referral in the majority of thyroid cancer patients following diagnosis. Improving their knowledge on the positive association between surgeon volume and better patient outcomes is key to ensuring that more vulnerable populations, such as older or comorbid adults with thyroid cancer, receive care from experienced providers. Similarly, physicians with very low thyroid cancer patient volume may be unfamiliar with the increasing literature on the volume-outcome relationship. It is also possible that local economic and insurance factors influence these decisions. Especially in community practice, collaborative referral relationships may be critical to consider. It is also conceivable that these physicians have not formed collaborative relationships with other specialist providers that care for their thyroid cancer patients. However, we recognize that selective referral of these patients to high-volume surgeons may not always be feasible. Additionally, surgeon volume is not the only factor to consider, as surgical center volume (usually an indicator of increased expertise and resources) is also important. Prior studies have demonstrated that travel to high-volume centers may require some patients to travel long distances to receive care. (37) Typically, older patients and those with comorbidities are the ones that may be unable or hesitant to travel longer distances. Indeed, transportation barriers were the second most cited reason in our survey decreasing likelihood of referral to a high-volume surgeon. Targeted educational interventions will help close knowledge gaps and tackle the existing issue of age disparities in thyroid cancer care.

To our knowledge, no study prior to ours has explored the reasons for not referring older thyroid cancer patients to high-volume surgeons, despite clinical evidence that thyroid cancer patients have improved outcomes with referral to a high-volume surgeon.(9–14, 16) We found that patient preference was the most common reason physicians cited that would decrease likelihood of referral of older thyroid cancer patients to a high-volume surgeon. This highlights the vital role of the patient in the shared decision-making process and the influence of patient preference on physicians’ treatment recommendations. Confidence in a local surgeon (who may or may not be a high-volume surgeon) was also identified as a barrier to referral to a high-volume surgeon in a potentially distant tertiary institution. This decision could be influenced by established provider relationships with and more availability of local surgeons, rather than their specific expertise in thyroid surgery. Alternatively, confidence in local surgeons may be justified, when considering their cumulative experience, track record and availability of ancillary services. It is also possible that community-based physicians are not confident that referral to high-volume surgeons would add clinically important benefit to their older thyroid cancer patients.

Strengths of this study include representation of both primary care physicians and specialists and the clinically relevant research questions. Limitations are similar to other survey studies and include risk for non-response bias, the possibility that physician report may differ from actual physician practice and the possibility that the clinical scenarios used in our survey may not be generalizable to all thyroid cancer patients.

In conclusion, our results have important implications for thyroid cancer patient care. Educational efforts should focus on improving access of vulnerable thyroid cancer patients, such as the elderly, to high-volume surgeons to optimize outcomes. Additionally, efforts should focus on primary care physicians and very low thyroid cancer patient volume physicians, in order to ultimately develop targeted interventions for older thyroid cancer patients and those with comorbidities, and eliminate age disparities and access gaps in health care delivery. These efforts may include improving organized identification of high-volume surgeons in the community and at a distance, as well as increasing social support resources for elderly thyroid cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center IDEA Fund to Dr. Papaleontiou. Dr. Papaleontiou is also funded by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K08 AG049684 and the Career Development Pilot Grant from the Cancer Control and Population Sciences Program at the University of Michigan. Dr. Haymart is funded by R01 CA201198 from the National Cancer Institute and by R01HS024512 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of the NIH or AHRQ. Support for the REDCap database was provided by a Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research grant (CTSA: UL1TR000433). The authors would also like to acknowledge Ms. Brittany Gay who assisted with data collection, manuscript formatting and review.

Contributor Information

Maria Papaleontiou, Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology and Diabetes, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, 24 Frank Lloyd Wright Drive, Lobby G, Room 1649, Ann Arbor, MI 48106.

Paul G. Gauger, Division of Endocrine Surgery, Department of General Surgery, Division Head – Endocrine Surgery, University of Michigan, 1500 East Medical Center Drive, TC 2920D, Ann Arbor MI 48109.

Megan R. Haymart, Divisions of Metabolism, Endocrinology and Diabetes and Hematology/Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, North Campus Research Complex, 2800 Plymouth Rd. Bldg. 16, Room 408E, Ann Arbor, MI 48109.

References

- 1.Davies L, Welch HG. Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973–2002. JAMA. 2006;295:2164–2167. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simard EP, Ward EM, Siegel R, Jemal A. Cancers with increasing incidence trends in the United States: 1999 through 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:118–128. doi: 10.3322/caac.20141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. [Accessed June 17, 2016];Common Cancer Types. Available at: www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/commoncancers.

- 5.SEER. [Accessed May 17, 2016];Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Available at: www.seer.cancer.gov.

- 6.Papaleontiou M, Haymart MR. Approach to and treatment of thyroid disorders in the elderly. Med Clin North Am. 2012;96:297–310. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rehman SU, Cope DW, Senseney AD, Brzezinski W. Thyroid disorders in elderly patients. South Med J. 2005;98:543–549. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000152364.57566.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christmas C, Makary MA, Burton JR. Medical considerations in older surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:746–751. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sosa JA, Bowman HM, Tielsch JM, Powe NR, Gordon TA, Udelsman R. The importance of surgeon experience for clinical and economic outcomes from thyroidectomy. Ann Surg. 1998;228:320–330. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang TJ, Liu SI, Mok KT, Shi HY. Associations of Volume and Thyroidectomy Outcomes: A Nationwide Study with Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155:65–75. doi: 10.1177/0194599816634627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Qurayshi Z, Robins R, Hauch A, Randolph GW, Kandil E. Association of Surgeon Volume With Outcomes and Cost Savings Following Thyroidectomy: A National Forecast. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2016;142:32–39. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dehal A, Abbas A, Al-Tememi M, Hussain F, Johna S. Impact of surgeon volume on incidence of neck hematoma after thyroid and parathyroid surgery: ten years’ analysis of nationwide in-patient sample database. Am Surg. 2014;80:948–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez-Sanchez C, Franch-Arcas G, Gomez-Alonso A. Morbidity following thyroid surgery: does surgeon volume matter? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:419–422. doi: 10.1007/s00423-012-1027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adkisson CD, Howell GM, McCoy KL, et al. Surgeon volume and adequacy of thyroidectomy for differentiated thyroid cancer. Surgery. 2014;156:1453–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.08.024. discussion 1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Youngwirth LM, Adam MA, Scheri RP, Roman SA, Sosa JA. Patients Treated at Low-Volume Centers have Higher Rates of Incomplete Resection and Compromised Outcomes: Analysis of 31,129 Patients with Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:403–409. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4867-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adam MA, Thomas S, Youngwirth L, et al. Is There a Minimum Number of Thyroidectomies a Surgeon Should Perform to Optimize Patient Outcomes? Ann Surg. 2017 Feb;265(2):402–407. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park HS, Roman SA, Sosa JA. Treatment patterns of aging Americans with differentiated thyroid cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:20–30. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haymart MR, Muenz DG, Stewart AK, Griggs JJ, Banerjee M. Disease severity and radioactive iodine use for thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:678–686. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Machens A, Dralle H. Age disparities in referrals to specialist surgical care for papillary thyroid cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:1312–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dillman DA, editor. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 2. New York: Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26:1–133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuyama H, Sugitani I, Fujimoto Y, Kawabata K. Indications for thyroid cancer surgery in elderly patients. Surg Today. 2009;39:652–657. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-3951-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bliss R, Patel N, Guinea A, Reeve TS, Delbridge L. Age is no contraindication to thyroid surgery. Age Ageing. 1999;28:363–366. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuijpens JL, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Lemmens VE, Haak HR, Heijckmann AC, Coebergh JW. Comorbidity in newly diagnosed thyroid cancer patients: a population-based study on prevalence and the impact on treatment and survival. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006;64:450–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen RC, Royce TJ, Extermann M, Reeve BB. Impact of age and comorbidity on treatment and outcomes in elderly cancer patients. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2012;22:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandelblatt JS, Yabroff KR, Kerner JF. Equitable access to cancer services: A review of barriers to quality care. Cancer. 1999;86:2378–2390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stavrakis AI, Ituarte PH, Ko CY, Yeh MW. Surgeon volume as a predictor of outcomes in inpatient and outpatient endocrine surgery. Surgery. 2007;142:887–899. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.09.003. discussion 887–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boudourakis LD, Wang TS, Roman SA, Desai R, Sosa JA. Evolution of the surgeon-volume, patient-outcome relationship. Ann Surg. 2009;250:159–165. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a77cb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kandil E, Noureldine SI, Abbas A, Tufano RP. The impact of surgical volume on patient outcomes following thyroid surgery. Surgery. 2013;154:1346–1352. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.04.068. discussion 1352–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loyo M, Tufano RP, Gourin CG. National trends in thyroid surgery and the effect of volume on short-term outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2056–2063. doi: 10.1002/lary.23923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saunders BD, Wainess RM, Dimick JB, Doherty GM, Upchurch GR, Gauger PG. Who performs endocrine operations in the United States? Surgery. 2003;134:924–931. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(03)00420-3. discussion 931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haymart MR, Banerjee M, Yang D, et al. Referral patterns for patients with high-risk thyroid cancer. Endocr Pract. 2013;19:638–643. doi: 10.4158/EP12288.OR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sogaard M, Thomsen RW, Bossen KS, Sorensen HT, Norgaard M. The impact of comorbidity on cancer survival: a review. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:3–29. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S47150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janssen-Heijnen ML, Houterman S, Lemmens VE, Louwman MW, Maas HA, Coebergh JW. Prognostic impact of increasing age and co-morbidity in cancer patients: a population-based approach. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;55:231–240. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chou WC, Chang PH, Lu CH, et al. Effect of Comorbidity on Postoperative Survival Outcomes in Patients with Solid Cancers: A 6-Year Multicenter Study in Taiwan. J Cancer. 2016;7:854–861. doi: 10.7150/jca.14777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Marth NJ, Goodman DC. Regionalization of high-risk surgery and implications for patient travel times. JAMA. 2003;290:2703–2708. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.20.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]