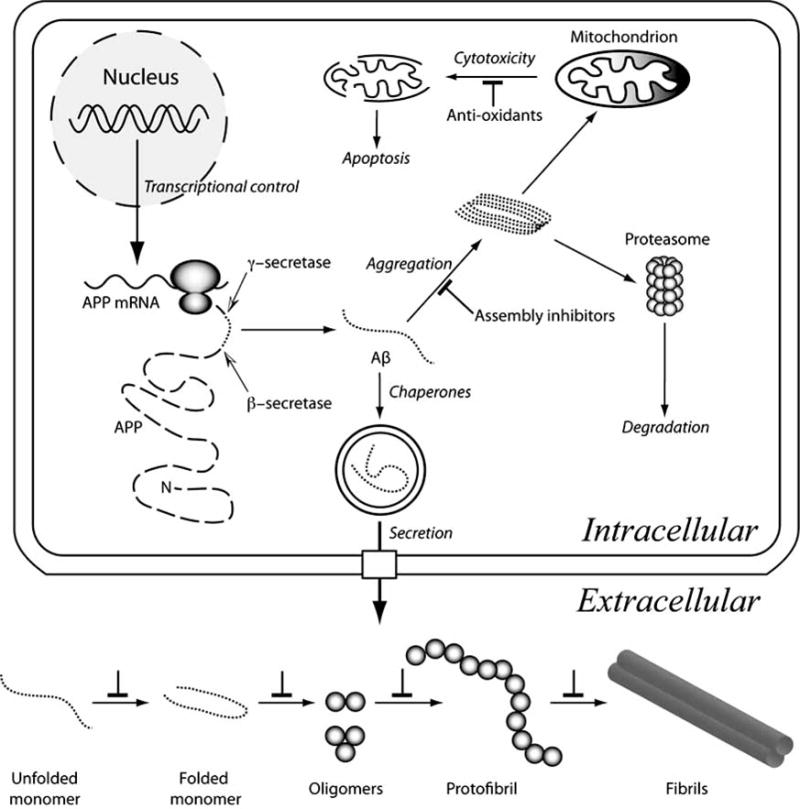

Fig. (1).

Aβ metabolism and assembly. Aβ (dotted lines) is produced by the sequential endoproteolytic cleavage of APP (dashed line). β-secretase cleavage (black-white arrowhead) produces the Aβ N-terminus, after which γ-secretase (black-white arrowhead) releases the Aβ C-terminus from APP. Transcriptional, translational, and endoproteolytic events all are targets for therapies to block Aβ production. The unstructured Aβ monomer may fold or aggregate intracellularly to produce toxic assemblies. One postulated cytotoxic mechanism is mitochondrial injury, which produces reactive oxygen species, mitochondrial injury, and apoptosis. Anti-oxidants could ameliorate redox effects directly. Assembly inhibitors would block this and other effects arising from formation of pathologic assemblies. Folding chaperones also would assist in this process. Aggregates may be eliminated through proteasomal digestion, but saturation of this system would result in cytotoxicity. Aβ secretion is a normal cellular process. Extracellular assembly of Aβ may occur in a variety of milieus. The micromolecular (pH, chemical composition) and macromolecular (proteins, lipids, carbohydrates) characteristics of these milieus differ, thus Aβ assembly pathways and kinetics also are likely to differ. Nevertheless, in vitro and in vivo experiments suggest that Aβ proceeds along a linear pathway comprising many populated monomer conformational states, a population of partially folded states (some of which facilitate peptide oligomerization), a more restricted distribution of oligomers (with distinct distributions for Aβ40 and Aβ42), protofibrils, and fibrils (of which multiple morphologies exist). Each of the inter-state transitions is a potential therapeutic target (⊥ symbol).