Abstract

Purpose

Ipilimumab was the first FDA-approved agent for advanced melanoma to improve survival and represents a paradigm shift in melanoma and cancer treatment. Its unique toxicity profile and kinetics of treatment response raise novel patient education challenges. We assessed patient perceptions of ipilimumab therapy across the treatment trajectory.

Methods

Four patient cohorts were assessed at different time points relative to treatment initiation: (1) prior to initiation of ipilimumab (n = 10), (2) at weeks 10–12 before restaging studies (n = 11), (3) at week 12 following restaging studies indicating progression of disease (n = 10), and (4) at week 12 following restaging studies indicating either a radiographic response or disease stability (n = 10). Patients participated in a semistructured qualitative interview to assess their experiences with ipilimumab. Quality of life was assessed via the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General and its Melanoma-specific module.

Results

Perceived quality of life was comparable across cohorts, and a majority of the sample understood side effects from ipilimumab and the potential for a delayed treatment response. Patients without progression of disease following restaging studies at week 12 held more positive views regarding ipilimumab compared to patients who had progressed.

Conclusion

Patients generally regarded ipilimumab positively despite the risk of unique toxicities and potential for delayed therapeutic responses; however, those with progression expressed uncertainty regarding whether taking ipilimumab was worthwhile. Physician communication practices and patient education regarding realistic expectations for therapeutic benefit as well as unique toxicities associated with ipilimumab should be developed so that patients can better understand the possible outcomes from treatment.

Keywords: Melanoma, Ipilimumab, Patient-reported quality of life, Qualitative research, FACT-M, FACT-G

Introduction

Patients with unresectable, advanced melanoma have historically had a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival of 6% and a median survival of 7.5 months [1, 2]. Since 2011, eight new agents that improve overall survival have been approved for use in patients with metastatic melanoma. Ipilimumab, a fully human antibody targeting CTLA-4, was the first of these new agents, receiving FDA approval on March 25, 2011 and became the standard of care front-line therapy for patients with advanced melanoma [3, 4].

Although improving overall survival, with durable long-term benefit in 20% of patients [5], ipilimumab has a unique toxicity profile that includes colitis, dermatitis, hepatitis, and endocrinopathies. Ipilimumab has the potential for a delayed radiographic response that can be observed 16 to 20 weeks after therapy initiation, with occasional radiographic enlargement of lesions or development of new lesions before eventual regression [6, 7]. Such toxicities and response kinetics raise novel patient education challenges.

Understanding patients’ experiences and level of trust with providers throughout ipilimumab treatment is critical to optimizing patient care. Such understanding will allow clinicians to anticipate psychosocial responses leading to treatment attrition, address quality of life and psychiatric morbidity, and will lead to developing ways to maximize clinician communication to enhance patients’ comprehension of ipilimumab therapy. We therefore sought to examine patient perspectives regarding their experiences with ipilimumab and quality of life at distinct time points throughout ipilimumab therapy.

Methods

Participants

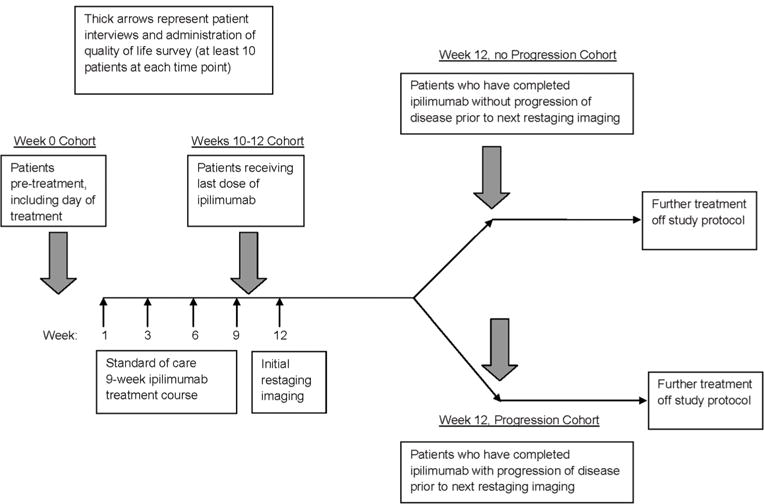

This single-center study was approved by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s institutional review board. Four distinct patient cohorts were recruited at different time points relative to treatment initiation and response: (1) the week prior to initiation of ipilimumab, (2) at weeks 10–12 prior to restaging studies, (3) at week 12 following restaging indicating a radiographic response or disease stability (week 12, no progression), and (4) at week 12 following restaging indicating disease progression (week 12, progression) (Fig. 1). All patients in this study consented to participate in a qualitative interview and complete a quantitative measure assessing health-related quality of life (HRQoL). We did not conduct serial interviews with the same patients and there was no overlap of patients across the four sample cohorts. We sought to limit burden on any single patient to participate in the study as we felt that asking the same patient contending with advanced cancer to participate in multiple interviews might be onerous. Second, designing a longitudinal study would have presented both logistical and conceptual challenges, in that it would require commitment from the same patients to participate in multiple interviews (raising the potential for patient dropout over time and ineligibility for patients who did not complete the ipilimumab treatment course), and the same patients would have reported their own changes over time, diminishing an understanding of unique patient perspectives regarding ipilimumab efficacy and benefit across treatment time points and disease response. Finally, it was necessary to interview two separate cohorts of patients at the week 12 time point as we sought to explore how a patient’s response to treatment may influence perceptions of the efficacy of ipilimumab and its value. Cohort size is consistent with qualitative research standards to attain thematic saturation [8].

Fig. 1.

Study schema

Eligible patients were 18 years of age or older, English-speaking, had advanced melanoma, and deemed appropriate candidates for ipilimumab by their oncologists. Patients were excluded if they previously received ipilimumab. Patients at week 12 who experienced extremely severe ipilimumab toxicities were excluded.

Procedure

Informed consent was obtained from all patients in the study. Patients underwent a semistructured interview either in person or via telephone (based on their preference) which was audio-recorded, transcribed, and qualitatively analyzed, and were also assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Melanoma (FACT-M) tool [9], a psychometrically sound instrument frequently utilized to assess HRQoL in clinical trials that include patients with melanoma [10]. The FACT-M consists of 43 items; 16 are specific to melanoma, with the remainder consisting of all items from the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) [11]. The FACT-M yields scores for a number of subscales, including the overall FACT-G total, physical (PWB), emotional (EWB), social (SWB), and functional well-being (FWB), and a melanoma score (MS). Eight FACT-M items related to surgery site were excluded since they were not applicable to the sample.

The interview aimed to understand patients’ concerns and experiences with ipilimumab throughout treatment. Two melanoma oncologists and a qualitative methods specialist generated questions to examine these issues. Four separate interview guides were developed, one per patient cohort (Online Resources 1–4), and overall explored: understanding of ipilimumab benefits, toxicities, and kinetics; views regarding imaging results during and following treatment; and expectations regarding future health. Several conceptual categories assessed were similar across cohorts, including patient understanding of ipilimumab’s kinetics and benefit, which we regarded as key conceptual categories given the novel nature of ipilimumab’s mechanism of action. Accordingly, we asked questions in these conceptual categories to all patients across the ipilimumab treatment trajectory. In contrast, we explored unique questions for certain sample cohorts, as we also sought to assess how a patient’s position in the treatment trajectory and their disease response may alter their perceptions of experience with ipilimumab. To minimize biased responses by prior knowledge of disease status or other outcomes, we collected data at patients’ visits before treatment administration or physician consultation and aside from the 2-week 12 cohorts prior to their being informed of disease status.

Data analysis

We employed a data analysis approach consistent with gold standard qualitative methods for interpreting semistructured interview data [12, 13], which included the use of multiple coders to achieve analyst triangulation [14] and iterative rounds of consensus analysis to ensure reliability [15]. Accordingly, a four-person team analyzed the interviews using inductive thematic text analysis [13, 16–20]. We used ATLAS.ti to manage coding [21].

Our data analysis process involved multiple stages, including a first phase of open coding [22], in which each team member independently read the transcripts, selected patient quotations deemed most relevant to our research objectives, and developed codes by reflecting on the meaning of such content. The team then met to achieve consensus about code names, their meaning, and assignment to patient narratives. We created a qualitative codebook of 74 codes (Online Resource 5).

Upon completion of transcript coding, we engaged in a secondary analysis to identify the most prevalent patterns of patient responses across each sample cohort. This secondary analysis entailed multiple steps. In step 1, we identified the five most frequently endorsed codes applied to patient narratives for each sample cohort during our first phase of open coding. This ranking and identification of code endorsement by frequency served to focus and guide our secondary analysis, as these codes represented the most recurring perceptions of the patient experience with ipilimumab in each cohort. In step 2, each coder read patient quotations linked with the most frequently endorsed codes to identify repeating observations across them. Step 3 entailed each coder conceptualizing these recurring observations and elucidating their meaning and through these process identified key themes; coders also identified illustrative patient quotations per theme. In step 4, coders subsequently met to reach consensus on the most prevalent and salient themes per cohort and to compare themes across cohorts. We found high concordance between coders regarding the most prominent themes per sample cohort. Analytic rigor was derived from successive rounds of iterative consensus work by the team.

The FACT-G total scores per cohort were computed as a sum of all 43 item scores. The four subscale scores were derived from the 27 items, and a FACT-M score was calculated. The total and subscale scores were set to missing data when applicable. Total and domain scores were summarized (i.e., mean, SD) for each cohort. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) techniques were used to statistically compare mean FACT-G/FACT-M subscale scores by sample cohort.

Results

Sample

The sample included 28 men (68%) and 13 women (32%) with locally advanced or metastatic melanoma interviewed between 2012 and 2014, aged 21 to 89 years (median = 63; SD = 13); a majority were married (59%) and primarily white (93%). Thirty patients (73.2%) had received no prior treatments. Twenty-six patients (63.4%) scored a 0 on ECOG performance status (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample demographics

| Characteristic | Total (N =41) N (%) |

Week 0 (n = 10) n (%) |

Weeks 10–12 (n =11) n (%) |

Week 12 No progression (n = 10) n (%) |

Week 12 Progression (n = 10) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 28 (68.3) | 6 (60.0) | 7 (63.6) | 7 (70.0) | 8 (80.0) |

| Female | 13 (31.7) | 4 (40.0) | 4 (36.4) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (20.0) |

| Age (median, range) | 63, 21–89 | 73, 42–89 | 60, 21–88 | 66, 51–74 | 54.5, 40–77 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 38 (92.7) | 10 (100.0) | 9 (81.8) | 10 (100.0) | 9 (90.0) |

| Black | 2 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) |

| Unknown | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic | 38 (92.7) | 10 (100.0) | 9 (81.8) | 9 (90.0) | 10 (100.0) |

| Hispanic | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unknown | 2 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2(18.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Disease stage at time of treatment | |||||

| Locally advanced, unresectable | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ballentyne Ia | 2 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| IIIC | 7(17.1) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (20.0) | 2 (20.0) |

| IV | 31 (75.6) | 8 (80.0) | 9 (81.8) | 6 (60.0) | 8 (80.0) |

| Number of systemic treatments prior to ipilimumab treatment | |||||

| 0 | 30 (73.2) | 6 (60.0) | 7 (63.6) | 8 (80.0) | 9 (90.0) |

| 1 | 6 (14.6) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (10.0) |

| 2 | 4 (9.8) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (9.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 4 | 1 (2.4) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ECOGb score at time of first ipilimumab dose | |||||

| 0 | 26 (63.4) | 5 (50.0) | 6 (54.5) | 8 (80.0) | 7 (70.0) |

| 1 | 14 (34.2) | 4 (40.0) | 5 (45.5) | 2 (20.0) | 3 (30.0) |

| 2 | 1 (2.4) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 24 (58.6) | 5 (50.0) | 3 (27.3) | 8 (80.0) | 8 (80.0) |

| Single | 8 (19.5) | 1 (10.0) | 5 (45.4) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (10.0) |

| Divorced | 6 (14.6) | 2 (20.0) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (10.0) |

| Widowed | 3 (7.3) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Mucosal melanoma patients were staged using the Ballentyne staging system

The Eastern Cooperative Collaborative Group score is a measure of cancer patients’ performance status, general well-being, and performance of activities of daily life

FACT-G and FACT-M findings

Descriptive statistics (i.e., mean, SD) for each FACT-G and FACT-M domain per cohort are presented (Table 2). Means did not significantly differ across cohorts (all p > 0.05). Higher scores on both the FACT-G and FACT-M indicate better patient quality of life, reflecting that a patient perceived lesser negative impact of having a diagnosis of melanoma on their overall quality of life. Patients did not answer the surgical items in the FACT-M as they were not relevant given our research objectives.

Table 2.

Means (SD) for FACT-G/FACT-M subscales, by sample cohort (N = 41)

| FACT-G

|

FACT-M | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (0–172) |

PWB (0–28) |

SWB (0–28) |

EWB (0–24) |

FWB (0–28) |

MS (0–64) |

|

| Sample cohort | ||||||

| Week 0 (n = 11)a | 127.0 (21.0) | 20.5 (5.3) | 23.0 (2.9) | 15.5 (5.1) | 17.8 (5.8) | 50.1 (7.8) |

| Week 9 (n = 11) | 130.1 (33.7) | 22.9 (5.2) | 21.3 (6.9) | 16.4 (7.2) | 18.8 (7.7) | 50.7 (11.0) |

| Week 12, no progression (n = 10)b | 130.8 (25.4) | 22.9 (5.5) | 21.5 (3.3) | 17.6 (4.8) | 20.6 (5.3) | 53.6 (7.0) |

| Week 12, progression (n = 9)c | 129.2 (19.3) | 21.8 (5.1) | 22.4 (4.7) | 16.3 (4.1) | 19.4 (4.2) | 49.2 (11.0) |

FACT-G Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General, FACT-M Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Melanoma Module, PWB physical well-being, SWB social well-being, EWB emotional well-being, FWB functional well-being, MS, Melanoma subscale. Higher scores on both the FACT-G and FACT-M indicate a better patient quality of life

n = 11 for the FACT-M scores for the week 0 sample cohort rather than n = 10 because one participant from this cohort completed the FACT-M survey but declined to participate in the semistructured interview

n = 9 for the melanoma-specific well-being score for the week 12 no progression sample cohort because one participant from this cohort did not provide answers to the melanoma-specific well-being items in the FACT-M survey

n = 9 for the FACT-M scores for the week 12 progression sample cohort rather than n = 10 because one participant from this cohort participated in the semistructured interview but declined to complete the FACT-M survey

Qualitative findings

As stated, in our first step of secondary analysis, we identified the top five codes assigned most frequently during coding per cohort (Table 3). We identified themes regarding perspectives of ipilimumab per cohort and present findings in order by frequency. Patient quotations per theme per cohort (Table 4) and an overview of findings (Table 5) are also presented.

Table 3.

Most frequently used codes per sample cohort

| Top 5 codes in order of frequency of use during coding | Week 0 cohort | Week 10–12 cohort | Week 12 No progression Cohort | Week 12 Progression cohort |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code 1 | Recommendation from medical team as influential in decision-making process to try ipilimumab | Confidence in perceived value of ipilimumab | Positive feelings with positive treatment outcomes from ipilimumab | Feelings of being well-informed about ipilimumab from health care professionals |

| Code 2 | Lack of interest in seeking information regarding ipilimumab | Positive expectations and hopes regarding treatment outcome | Ipilimumab side effects perceived as tolerable or minimal | Ipilimumab side effects perceived as tolerable or minimal |

| Code 3 | Fear and anxiety regarding starting ipilimumab | Ipilimumab side effects perceived as tolerable or minimal | Perceived value of ipilimumab regarded as possibility of disease stabilization or increased survival | Value of ipilimumab perceived as uncertain |

| Code 4 | Acceptance of ipilimumab time course | Ipilimumab regarded more positively than other treatment options | Positive expectations and hopes regarding treatment outcomes | Positive understanding of ipilimumab time course |

| Code 5 | Value of ipilimumab perceived as uncertain | Cautious optimism regarding benefit of ipilimumab | Confidence in perceived value of ipilimumab | Feeling uncertain regarding ipilimumab’s efficacy |

Table 4.

Key themes by sample cohort and supporting participant quotations

| Sample Cohort | Key Themes | Supporting Participant Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Week 0 | Trust in treating facility and medical staff | “I’m in the best place in the world to get treatment. I’m going to do what they recommend. I’m not going to be a Monday morning quarterback and try [to] become an expert on health and I’m not going to read and I’m not going to listen to anybody on the computer” |

| Fear regarding starting ipilimumab and uncertainty regarding outcome | “I guess nobody knows, and the doctor’s as much as said, well, whether I, you know—and he answers my question about what are the odds of making this go away and so forth, and his answer I think was, ‘Wait till, wait till 12 weeks from now and we’ll talk about it.’ But, you know, that’s a wait and see, and an observation. I understand that.” | |

| Comfort with treatment timeline | “Um, I’m okay with it. I guess you know, 3 or 4 months doesn’t seem to worry me too much.” | |

| “As long as it’s [ipilimumab] going to work.” | ||

| Weeks 10–12 | Experiencing symptom relief fostered hope in a positive outcome | Participant: “I’m gonna have one [scan] in 2 weeks. I’m sure that it’ll be good, because I feel good.” |

| Interviewer: “You’re confident because you feel good?” | ||

| Participant: “Very confident.” | ||

| “I’m anxious to see after the last infusion, to see the next scan. Maybe it works, perhaps, the initial. But the one 4 weeks after that, we should know more definite position where the tumor is and if it’s shrunk, or got bigger. But we’re confident that—I’m sure it’s gotten better. Before my eye was twitching, I had—I’m talking November now, right, so its 8 months ago, before any kind of treatment, there was concerns. You know, losing eyesight—you know, with surgery. But there was those more effects before treatment, and now I don’t have the numbness or the constant rubbing of the eye. So I am, I’m hopeful, positive, that through all the treatments I’ve taken, and especially the ipilimumab, that it shrunk, the tumor has shrunk.” | ||

| Balancing hopes for a positive outcome with knowledge that treatment could fail | “As far as the drug effect on myself, you know, I just, I wish there was more to read about it, and, you know, when you’re going this, a lot of its emotional. And some days I say with the ipilimumab, I’m going to beat this, and some days I wake up and say the ipilimumab’s not working and I’m going to die.” | |

| “How long it’s going to work, I don’t know. How long it’s going to keep it away, we don’t know. But you know what? I know that I’m feeling good today And…tomorrow is another day.” | ||

| Comparing experience with ipilimumab to prior therapies | “I’ve had radiation. I’ve had surgery. I mean, given the choice, obviously this [ipilimumab] is the best of the three, because even when it has gone bad, I feel okay the next day…Radiation…was the worst I’d ever felt. I was curled up in the fetal position. I couldn’t move. I was in a lot of pain. I couldn’t eat. Couldn’t do anything. So the ipilimumab…is light years above having to go through a treatment like that.” | |

| Week 12, no Progression | Cautious optimism regarding ipilimumab’s efficacy and hope for continued success | “This is wonderful. If this were 10 years ago, I think I would have a death sentence, and this gives me an opportunity, you know, wonderful, wonderful thing to let me live, potentially live, and actually become free from this, this horrible thing that happened to me.” |

| “…you can’t expect good, good all the time…it’s good to hear good news but you always have to keep yourself open that it’s not always going to be good news.” | ||

| Experience of minimal side effects and limited impact on quality of life | “I absolutely love it [ipilimumab]. I was very, very nervous because I was made aware of all the side effects and I had none of them.” | |

| “I would say go for it. My experience at least has been positive, certainly not negative. I have not had any side effects. It hasn’t really interfered with my quality of life.” | ||

| Week 12, Progression | High anxiety regarding future treatment success and ipilimumab’s value | “I really don’t know what the future holds, or…how long the future’s gonna be forme. And that’s…the biggest anxiety…its uncertainty It’s uncertainty. You know, of whether it’s, it’s, it’s gonna be effective or not, and if it is effective, how long, how long it will last. Will it, you know, could it be a complete remission? Will it—is it just slowing it down? I mean, it’s the uncertainty of those, those issues.” |

| “I hope this—I didn’t expect the last one to show reductions, but I’m hoping this one will, so if it doesn’t, or if it shows it’s continuing to grow, then I’ll, then I’ll have concerns that the drug isn’t doing what it—what we hoped it would do…I’m hoping that it’s, it’s going to you know, send the cancer in both spots into remission and, and prevent it from spreading anywhere else. That’s my expectation.” | ||

| “So far there hasn’t been much value…it [ipilimumab] works for some folks, it doesn’t for some other folks…but we just don’t know because we don’t know.” | ||

| Experiencing minimal side effects led to positive views regarding the physical exposure of taking ipilimumab | “I was absolutely certain that I’d get some form of colitis, and the fact that that didn’t happen surprised me.” | |

| “I had no reactions at all…it was almost as if just water had been injected, because I had no side effects at all.” | ||

| Mixed views regarding acceptance of time duration to see a treatment outcome | “If that’s how the drug works, then that is how it works.” | |

| Interviewer: “So throughout this treatment course then how have you felt about not knowing about whether the ipilimumab is working or not?” | ||

| Participant: “I’ve been all right with it. I mean it’s just, you know, again, its part of the education. I understood that, you know, if you think of it simply, chemo kills the cancer, ipilimumab tries to get your body to stop the cancer, you know, and that’s just going to take longer than zapping it with something to kill it. So, you know, I think I had the expectation in my mind that, you know, I’m going on 6 months and, you know, we’ll see.” | ||

| “The ipilimumab, the last treatment was 2 weeks ago, but it takes another 6–8 weeks for it to become fully effective, which is kind of a pain in the ass, or neck, but it is what it is.” |

Table 5.

Key thematic findings by sample cohort

| Sample cohort | Key Thematic Findings |

|---|---|

| Week 0 | Trust in treating facility and medical staff |

| • Many participants considered their treating institution to be the optimal place to receive treatment for advanced melanoma | |

| • Self-initiated research regarding ipilimumab was minimal prior to commencing treatment | |

| • Participants based decision to receive ipilimumab on physician recommendations, perceived competence of physicians, and high value in their treating institution | |

| Fear regarding starting ipilimumab and uncertainty regarding outcome | |

| • Expressions of fear and anxiety regarding beginning treatment were prominent | |

| • These emotions were driven by skepticism regarding ipilimumab’s potential because participants had experienced prior treatment failure; concerns about potential side effects; knowledge that they had few remaining treatment options; and fears about having advanced cancer in general | |

| • Participants were in a “wait and see” mode regarding determination of ipilimumab’s value | |

| Comfort with treatment timeline | |

| • Participants held mixed views regarding comfort with frequency of treatment visits; some were indifferent, others were pleased with few required treatment visits | |

| • They accepted logistical requirements with the treatment schedule as well as the potential kinetics of treatment response as long as the drug proved effective | |

| • Participants were comfortable with uncertainties with pattern of treatment response as the cost of getting better | |

| Weeks 10–12 | Experiencing symptom relief fostered hope in a positive outcome |

| • Many participants reported disease-related symptom relief during treatment, and attributed this experience to taking ipilimumab | |

| • Symptom relief prompted many to feel optimistic and relatively certain regarding a positive treatment response | |

| Balancing hopes for a positive outcome with knowledge that treatment could fail | |

| • Participants described two possible treatment outcomes, disease progression or stabilization, and settled on hoping for the best | |

| • Some struggled between maintaining optimism regarding ipilimumab’s efficacy and negative feelings toward the possibility of treatment failure | |

| • Cautious optimism was rooted in the experience of symptom relief and limited side effects from ipilimumab | |

| Comparing experience with ipilimumab to prior therapies | |

| • A majority of participants were surprised that they experienced minimal or tolerable side effects in comparison to those experienced while receiving prior therapies | |

| • Most regarded ipilimumab to offer a higher quality of life than other therapies | |

| • They preferred ipilimumab over chemotherapy as they perceived it as a boost to their overall health | |

| Week 12, no progression | Cautious optimism regarding ipilimumab’s efficacy and hope for continued success |

| • Many participants were hopeful regarding a future benefit because they had received positive results from ipilimumab to date, yet were aware their disease could progress | |

| • Optimism was tempered by realistic thoughts about the uncertainty of their disease and the possibility of recurrence | |

| Experience of minimal side effects and limited impact on quality of life | |

| • Most participants did not experience significant side effects, and those received were tolerable, not severe, and subsided relatively quickly | |

| • Many could maintain regular life routines during treatment | |

| Week 12, progression | High anxiety regarding future treatment success and ipilimumab’s value |

| • Due to lack of positive results to date participants were uncertain regarding the potential of a positive future outcome | |

| • It was challenging for participants to assess ipilimumab’s value, as they were aware they could still receive a positive future response despite experiencing disease progression | |

| • Some remained hopeful about the possibility of disease stabilization or regression, understanding ipilimumab’s mechanism of action | |

| Experiencing minimal side effects led to positive views regarding the physical exposure of taking ipilimumab | |

| • Most participants encountered minimal side effects | |

| • Many felt ipilimumab could provide a high quality of life during treatment | |

| Mixed views regarding acceptance of time duration to see a treatment outcome | |

| • Participants differed regarding comfort level with the prolonged time course required to assess treatment outcome | |

| • Some accepted the time course based on an understanding of ipilimumab’s mechanism of action, others were frustrated by it |

Week 0 cohort: Week prior to initiation of ipilimumab

Overview

Key themes identified for this cohort included (1) trust in patients’ treating facility and medical staff which reduced motivations to independently research ipilimumab, (2) concerns regarding beginning treatment and lack of certainty regarding therapeutic response, and (3) relative comfort with treatment schedule and time course needed to evaluate treatment response.

Theme 1: Trust in treating facility and medical staff

Week 0 patients had high trust in their physicians’ knowledge regarding ipilimumab because they considered their treating institution as “the best place in the world to get treatment” and their physicians to be leaders in the field. Consequently, these patients did not conduct research about the drug prior to initiation.

Theme 2: Fear regarding starting ipilimumab and uncertainty regarding outcome

Week 0 patients voiced fears about starting ipilimumab driven by prior treatment failure leading to less optimism about possible success of ipilimumab, concerns about potential toxicities, knowledge that ipilimumab represented one of their few remaining treatment options, and fears about having advanced cancer. Patients’ uncertainty was conceptualized by a “wait and see” approach; they had minimal confidence that ipilimumab could prove effective and needed to see outcomes before determining its value. However, they demonstrated good understanding that ipilimumab was not intended to cure their disease but rather achieve disease control.

Theme 3: Comfort with treatment timeline

Patients compared ipilimumab therapy with chemotherapy and regarded it to be “easier to handle” providing greater quality of life. In particular, they preferred that the treatment did not require multiple weekly visits and that visits were spread across 9 weeks. Patients accepted the treatment schedule requirements (one dose every 3 weeks for a total of up to four doses), as well as the potential delayed kinetics of treatment response, as long as the drug was effective. The overall spirit regarding acceptability with the timeline was expressed as “if that’s how the drug works, then that’s how it works.” Regret at not having started ipilimumab sooner was also expressed by these patients.

Weeks 10–12 cohort: Prior to restaging studies

Overview

Key themes for this cohort included (1) association between symptom relief during treatment and hope to achieve a positive therapeutic outcome, (2) balancing hopes for clinical benefit with realistic beliefs that ipilimumab may not provide a lasting benefit, and (3) comparing experiences with prior melanoma therapies to ipilimumab.

Theme 1: Experiencing symptom relief fostered hope in a positive outcome

Week 10–12 patients perceived that while taking ipilimumab their cancer-related symptoms subsided, which they attributed to the therapy. These patients indicated that they felt physically better than they had prior to taking ipilimumab. This encouraged patients to feel optimistic that ipilimumab was working and so confident they felt no need to plan for consequences of tumor enlargement. One patient theorized that if his disease progressed, ipilimumab would “keep it away.” Week 10–12 patients felt that if ipilimumab had been available earlier they would not have been diagnosed with advanced melanoma and regarded ipilimumab as a second chance at life.

Theme 2: Balancing hopes for a positive outcome with knowledge that treatment could fail

Patients did not discount uncertainties associated with treatment, however. Patients in this cohort expressed they were hoping for the best, rather than feeling certain of receiving a positive outcome, revealing their struggle between maintaining optimism regarding ipilimumab’s efficacy and coping with negative feelings toward the possibility of treatment failure. These patients explicitly chose to be optimistic, using the word “hope” instead of “know” in their responses about the drug’s possible positive efficacy, reflecting an understanding of the range of treatment outcomes, while illustrating optimistic expectations. Such cautious optimism originated from a focus on present outcomes, including symptom relief and experience of limited toxicities.

Theme 3: Comparing experience with ipilimumab to prior therapies

Week 10–12 patients were pleasantly surprised by their ipilimumab treatment experience, as they encountered minimal toxicities and improved quality of life, and compared it favorably to prior treatment experiences. They understood and felt positively that ipilimumab targets the immune system and that it is a cutting-edge treatment. Patients regarded it to be a boost to their health, rather than an introduction of harmful agents into their system.

Week 12 cohort/no progression: Following restaging studies indicating no disease progression

Overview

Key themes for week 12 without progression patients included (1) approaching future health with cautious optimism, as they hoped for disease stabilization yet were aware they could receive bad news at any time, and (2) an overall experience of limited side effects during treatment.

Theme 1: Cautious optimism regarding ipilimumab’s efficacy and hope for continued success

Week 12 patients without disease progression sustained high hope regarding future expectations based on positive results from ipilimumab thus far; they believed that ipilimumab would continue to work after treatment completion, potentially stabilizing their disease and improving survival. However, such optimism was tempered by feelings of uncertainty about their disease and the possibility of recurrence. Patients were joyful after hearing good news about their disease but remained aware and prepared that a positive result could be short-lived.

Theme 2: Experience of minimal side effects and limited impact on quality of life

Overall, this cohort reported minimal side effects as a result of ipilimumab treatment. They were informed of a laundry list of possible side effects before commencing therapy, leading to initial anxiety, yet overall these patients experienced few serious side effects. For example, they expressed surprise and gratitude that receiving treatment in the morning would not preclude them from executing their routine afternoon activities. Patients in this cohort happily reported experiencing either only one or two minor side effects such as itchiness, fatigue, or diarrhea, which subsided relatively quickly, or no side effects whatsoever. In general, patients felt ipilimumab was “a piece of cake” as compared to other prior treatments.

Week 12 cohort/ progression: Following restaging studies indicating disease progression

Overview

Key themes for week 12 progression patients included (1) doubts as to ipilimumab’s ability to produce a positive result, (2) noted minimal side effects during treatment, and (3) mixed perspectives regarding level of comfort with the time duration required to determine the therapeutic response that one may receive from ipilimumab.

Theme 1: High anxiety regarding future treatment success and ipilimumab’s value

Patients in this cohort spoke of heightened anxiety and uncertainty relative to their health status. Faced with their imaging results, they expressed concern about their health and a somewhat negative outlook regarding their prognosis. Regarding their prognosis as uncertain, they were not able to reach a conclusion as to the ultimate value of having taken ipilimumab on their health. As these patients were in a “wait and see” mode—they experienced disease progression but were aware that ipilimumab could still provide a positive future therapeutic response—they felt it difficult to determine whether ipilimumab had been of value. Yet, a spirit of hope regarding the future despite negative scan results remained for these patients in light of ipilimumab’s mechanism of action.

Theme 2: Experiencing minimal side effects led to positive views regarding the physical exposure of taking ipilimumab

These patients’ physical experiences with ipilimumab were similar to those of week 12 patients without disease progression. They also expressed surprise that they did not experience more severe side effects. Encountering limited side effects led many patients to regard ipilimumab to be a drug that allows for a high quality of life.

Theme 3: Mixed views regarding acceptance of time duration to see a treatment outcome

Patients in this cohort held differing perspectives regarding level of comfort with the prolonged time course required to reach a final assessment of ipilimumab’s therapeutic effect. A number of patients seemed to have psychologically come to terms with it, following education regarding this characteristic of the drug prior to treatment. They understood that immunotherapy differs from other cancer therapies where a more immediate assessment of disease-related outcomes can be possible. Knowledge and acceptance of ipilimumab’s mechanism of action helped to minimize concerns about the drug’s potential efficacy. Yet other patients in this cohort felt pessimistic, frustrated, or anxious about the time duration needed to see an ultimate outcome from ipilimumab. These patients also understood ipilimumab’s prolonged time course but expressed greater emotional distress in light of it.

Discussion

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine proposed that patient-centered care must guide clinical decision making to ensure top-quality medical practice throughout the nation [23]. Patient-centered medicine emphasizes the patient perspective and the cooperative work of both clinicians and patients to achieve best outcomes. Patient perceptions of immune checkpoint inhibitors have not been extensively examined but are important in optimizing patient education regarding the unique toxicity profile and kinetics of treatment response associated with these novel agents.

This study is unique in its examination of patient perception of an immune checkpoint inhibitor in distinct patient cohorts at different treatment time points. To date, it is the only study to examine variations in patient perception based upon imaging results for a drug for which apparent progression does not necessarily mean lack of efficacy. Ipilimumab is associated with pseudo-progression in approximately 10% of patients [24], and patient perspectives during this period of uncertainty are understudied. Inaccurate patient views regarding potential benefit from ipilimumab (approximately 20% of patients on ipilimumab therapy will see a therapeutic benefit [3]) may lead patients to prematurely switch to alternative therapies or continue treatment inappropriately.

Importantly, more similarities than differences in patient perceptions of and experiences with ipilimumab emerged across the four sample cohorts. This was true regarding HRQoL, where levels of physical, social, emotional, and functional well-being were comparable across the overall sample, and melanoma-specific well-being, which reflect the manageable ipilimumab side effects experienced by all patients across the treatment trajectory.

It was common for patients in the weeks 10–12 and both week 12 cohorts to encounter limited or tolerable side effects leading to the general view that ipilimumab has minimal negative effects upon HRQoL. Patients often compared side effects experienced with ipilimumab to those experienced with prior therapies and uniformly concluded that ipilimumab was more tolerable in comparison. Our sample is limited in that patients who experienced severe side effects from ipilimumab prior to week 12 were excluded from study participation in the week 12 cohorts. As such, our patients in the week 12 cohorts were inherently more likely to report minimal toxicities and impact on HRQoL. Nevertheless, these findings, albeit in a small sample, may help to inform patient education regarding ipilimumab’s side effect profile. Specifically, physicians could inform patients that while certain side effects associated with ipilimumab are severe (e.g., colitis, hypophysitis), it is possible that patients may experience minimal treatment side effects.

Secondly, patients in the weeks 10–12 and 12 cohorts approached the likelihood of ultimately receiving a positive disease outcome from ipilimumab with cautious optimism. They engaged in a cognitive process of balancing positive hopes and in some cases expectations, with an understanding that there was a chance they could not see a lasting positive benefit. Third, patients in the week 0 and week 12 with progression cohorts experienced anxiety and uncertainty regarding taking ipilimumab. These patients expressed emotional concerns toward taking the drug, either prospectively or retrospectively; worries they would not receive a therapeutic benefit were present among week 0 patients, and week 12 with progression patients described distress that receiving a future positive outcome was limited given negative results received thus far.

Perceptions regarding level of comfort with the extended timeline to assess treatment efficacy were prominent for both the week 0 and week 12 with progression cohorts. While week 0 patients were more comfortable with the timeline, week 12 with progression patients expressed mixed views, including frustration with the prolonged period of time to determine an outcome from ipilimumab.

Distinctions in patient perspectives between the cohorts were also identified. The views of week 0 patients were most unique, likely because they had not yet commenced treatment and had no direct experiences with ipilimumab. Their perceptions regarding the drug derived from their decision making to take ipilimumab and their emotions toward it before treatment. Patients in the week 10–12 cohort described their cancer-related symptoms during therapy, with many reporting a minimization of such symptoms.

Finally, the 2-week 12 cohorts expressed mixed views regarding ipilimumab’s perceived value. Not surprisingly, treatment response strongly influenced patients’ perception of ipilimumab’s utility. While the week 12 without progression cohort reflected more positive views regarding the drug’s value, week 12 with progression patients expressed uncertainty about whether taking ipilimumab was worthwhile, resulting from being in a “wait and see” mode regarding whether they could ultimately achieve a positive future response. This finding reflects that imaging results relatively determined appraisal of ipilimumab’s worth. Our finding that patients who had progressed on ipilimumab may remain hopeful regarding a positive future therapeutic outcome challenges physicians to address such desires given the limited chance of a lasting treatment benefit demonstrated to date.

The study is limited in its modest sample size. Further research is required to confirm study findings in larger more diverse patient populations. While our small sample inhibited our ability to examine demographic or medical characteristics as covariates of HRQoL effects, it was required to allow us to feasibly collect and analyze the in-depth interviews employed by the study. This qualitative approach was appropriate given our minimal understanding of patient perspectives regarding ipilimumab treatment and our desire to generate hypotheses for further study. Future work may explore perception and psychological management of uncertain benefit from ipilimumab therapy among patients at week 12 of receiving treatment and expanding the patient sample to include those who did not complete ipilimumab therapy due to intolerable toxicities. Evaluation of patient experiences with ipilimumab by those who report more severe side effects would help to inform patient education regarding the impact of ipilimumab on HRQoL. Further, patients may have been more positive about medical and drug research than patients who declined to participate.

Additionally, it will be important to examine issues explored in this study among patients treated in community settings where physician practice patterns are beginning to increase their use of immune checkpoint inhibitors such as ipilimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, or the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab. Our finding that patients significantly trusted their physicians and medical facility may be biased, as our patients were treated at a specialty cancer center. Further work could explore the nature of physician trust among patients treated at community practice centers regarding selection of ipilimumab as a treatment for advanced melanoma. Our study evaluated patient experiences with the use of ipilimumab as their first immunological checkpoint blockade inhibitor. In the future, many individuals experiencing metastatic melanoma who receive ipilimumab will have already experienced disease progression to agents targeting PD1 (e.g., nivolumab and pembrolizumab) or BRAF (e.g., vemurafenib and cobimetinib or dabrafenib and trametinib); our findings may not be fully applicable to the experiences of future patients receiving ipilimumab.

Finally, we did not engage in a member checking exercise to support our creation of code categories and generation of final thematic findings, but this strategy could be adopted in future research as immunotherapeutic options expand. Additionally, we did not formally assess data saturation. However, as is typical in the use of semistructured interviews in qualitative inquiry, our interviewers did not use the guides as scripts but rather as prompts to elicit patients to share their unique perspectives.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate promise regarding high patient comprehension of ipilimumab’s treatment kinetics, a tolerable side effect profile that compares favorably with other treatments for advanced melanoma, and the ability of patients to maintain realistic hopes and appreciate novel treatment options. We encourage an enhanced consideration of patient perspectives regarding immunotherapy treatment, which will continue to help shape physician communication practices, patient education materials, and anticipation of patient concerns, both physical and emotional, in the advanced treatment setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the significant contribution of Dr. Thomas Atkinson who assisted with quantitative data analysis. Preliminary findings from interviews conducted with participants in the two week 12 sample cohorts highlighted in this paper were previously presented at the Tenth Anniversary International Congress of The Society for Melanoma Research. This work was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb [RFP-US-11-CA184-010] initially awarded to Dr. Jason Luke, and subsequently held by Drs. Richard D. Carvajal and Jennifer L. Hay, and also by the Melanoma Disease Management team at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. This project was additionally supported by a National Institutes of Health Support Grant [P30 CA08748-48], which provides partial support for the Behavioral Research Methods Core Facility in the Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, which was used in conducting this investigation.

Footnotes

Richard D. Carvajal and Jennifer L. Hay are co-last authors.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00520-017-3621-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Compliance with ethical standards All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial relationship with the organization that sponsored this research. The authors have full control of all primary data and allow review of our data if requested.

Disclosures None.

References

- 1.Barth A, Wanek LA, Morton DL. Prognostic factors in 1,521 melanoma patients with distant metastases. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balch CM, Soong SJ, Gershenwald JE, Thompson JF, Reintgen DS, Cascinelli N, Urist M, McMasters KM, Ross MI, Kirkwood JM, Atkins MB, Thompson JA, Coit DG, Byrd D, Desmond R, Zhang Y, Liu PY, Lyman GH, Morabito A. Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients: validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3622–3634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, Akerley W, van den Eertwegh AJ, Lutzky J, Lorigan P, Vaubel JM, Linette GP, Hogg D, Ottensmeier CH, Lebbé C, Peschel C, Quirt I, Clark JI, Wolchok JD, Weber JS, Tian J, Yellin MJ, Nichol GM, Hoos A, Urba WJ. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, O’Day S, Weber J, Garbe C, Lebbe C, Baurain JF, Testori A, Grob JJ, Davidson N, Richards J, Maio M, Hauschild A, Miller WH, Jr, Gascon P, Lotem M, Harmankaya K, Ibrahim R, Francis S, Chen TT, Humphrey R, Hoos A, Wolchok JD. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schadendorf D, Hodi FS, Robert C, Weber JS, Margolin K, Hamid O, Patt D, Chen TT, Berman DM, Wolchok JD. Pooled analysis of long-term survival data from phase II and phase III trials of ipilimumab in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1889–1894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolchok JD, Neyns B, Linette G, Negrier S, Lutzky J, Thomas L, Waterfield W, Schadendorf D, Smylie M, Guthrie T, Jr, Grob JJ, Chesney J, Chin K, Chen K, Hoos A, O’Day SJ, Lebbé C. Ipilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2, dose-ranging study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:155–164. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maker AV, Phan GQ, Attia P, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Topalian SL, Kammula US, Royal RE, Haworth LR, Levy C, Kleiner D, Mavroukakis SA, Yellin M, Rosenberg SA. Tumor regression and autoimmunity in patients treated with cytotoxic t lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 blockade and interleukin 2: a phase I/II study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:1005–1016. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.03.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cormier JN, Askew RL. Assessment of patient reported outcomes (PROs) in melanoma patients. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2011;20:201–213. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grob JJ, Amonkar MM, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, Dummer R, Mackiewicz A, Stroyakovskiy D, Drucis K, Grange F, Chiarion-Sileni V, Rutkowski P, Lichinitser M, Levchenko E, Wolter P, Hauschild A, Long GV, Nathan P, Ribas A, Flaherty K, Sun P, Legos JJ, McDowell DO, Mookerjee B, Schadendorf D, Robert C. Comparison of dabrafenib and trametinib combination therapy with vemurafenib monotherapy on health-related quality of life in patients with unresectable or metastatic cutaneous BRAF Val600-mutation-positive melanoma (COMBI-v): results of a phase 3, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1389–1398. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00087-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J, Eckberg K, Lloyd S, Purl S, Blendowski C, Goodman M, Barnicle M, Stewart I, McHale M, Bonomi P, Kaplan E, Taylor S, IV, Thomas CR, Jr, Harris J. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brinkmann S, Kvale S. InterViews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denzin NK. AldineTransaction. New Brunswick, NJ: 2009. The research act: a theoretical introduction to sociological methods. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, Olsen K, Spiers J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2002;1:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. AltaMira Press; Lanham, MD: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. Sage Publications; London: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saldańa J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage Publications; London: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friese S. Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS.ti. Sage Publications; London: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldańa J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolchok JD, Hoos A, O’Day S, Weber JS, Hamid O, Lebbé C, Maio M, Binder M, Bohnsack O, Nichol G, Humphrey R, Hodi FS. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7412–7420. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.