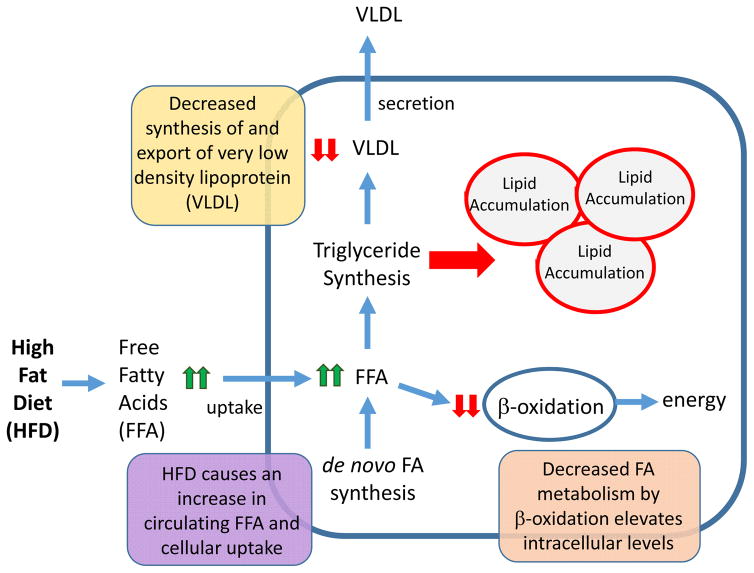

Figure 2. Altered hepatic metabolic pathways leading to NAFLD.

The liver is central to the maintenance of whole-body lipid homeostasis. Mechanistically, uptake of dietary fats is facilitated by release of bile acids that are synthesized in the liver and secreted by the gall bladder into the intestine. Bile salts emulsify fat, creating free fatty acids (FFAs) and monoglycerides, which are rapidly absorbed by enterocytes of the intestine. In the intestine, FFAs and monoglycerides are resynthesized into triglycerides, which are packaged into chylomicrons and are taken up by the liver via receptor-mediated endocytosis. The liver is also is responsible for converting carbohydrates and protein into FFAs, which are packaged into triglycerides and exported from the liver as VLDL. The liver is also the primary source of β-oxidation that serves to metabolize FFAs to produce energy in the form of ATP, as well as to generate ketone bodies that are used as an alternative fuel source during periods of fasting. Altogether the balance between lipid uptake and release, triglyceride synthesis and β-oxidation helps to preserve energy homeostasis in the liver. Disruption of these processes by a high-fat diet (HFD) is accompanied by aberrant lipid accumulation in the liver, which leads to a cascade of pathologies ranging from steatosis to hepatocellular carcinoma. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) can also promote nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), either alone or with a HFD, by increasing FFA uptake, increasing de novo lipogenesis, decreasing triglyceride export via VLDL, and/or decreasing FFA β-oxidation.