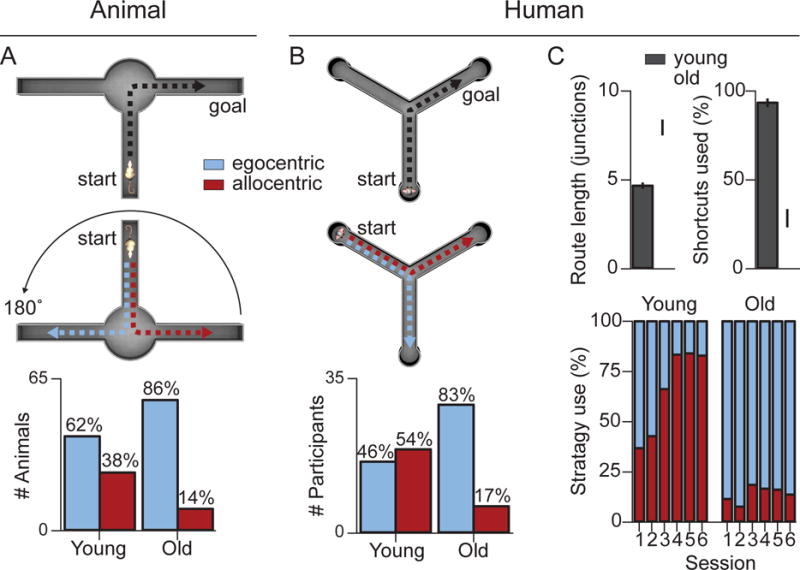

Figure 4. Correspondence of age-related navigational deficits in rodents and humans: Strategy preferences.

(A) In the T-maze task, an egocentric strategy was coded when a rat ‘turned right’ following 180° rotation of the start location and an allocentric strategy was coded when an animal moved to the same learned goal location relative to the external cues. Older rats overwhelmingly revealed an egocentric strategy on the probe trials (Barnes et al., 1980). (B) In the virtual Y-maze task, an egocentric strategy was coded when a human participant ‘turned right’ following displacement to a new starting location and an allocentric strategy was coded when the participant moved to the same learned goal location in absolute space (Rodgers et al., 2012). As with the rodent study (A), older adults spontaneously chose an egocentric strategy over an allocentric strategy compared to younger adults. (C) Similar results are observed in an environmental space task (top), in which older adults were impaired at switching from a learned route to a more optimal allocentric strategy, leading to increased route lengths and a reduced use of shortcuts (Harris and Wolbers, 2014). Critically, in a task that distinguishes between allocentric and two egocentric (beacon/associative cue, not shown) strategies (bottom), older adults remain biased toward using an egocentric navigation strategy (Wiener et al., 2013). These results suggest that egocentric strategy preferences are difficult to overcome for older adults, even when they are maladaptive and lead to suboptimal task performance.