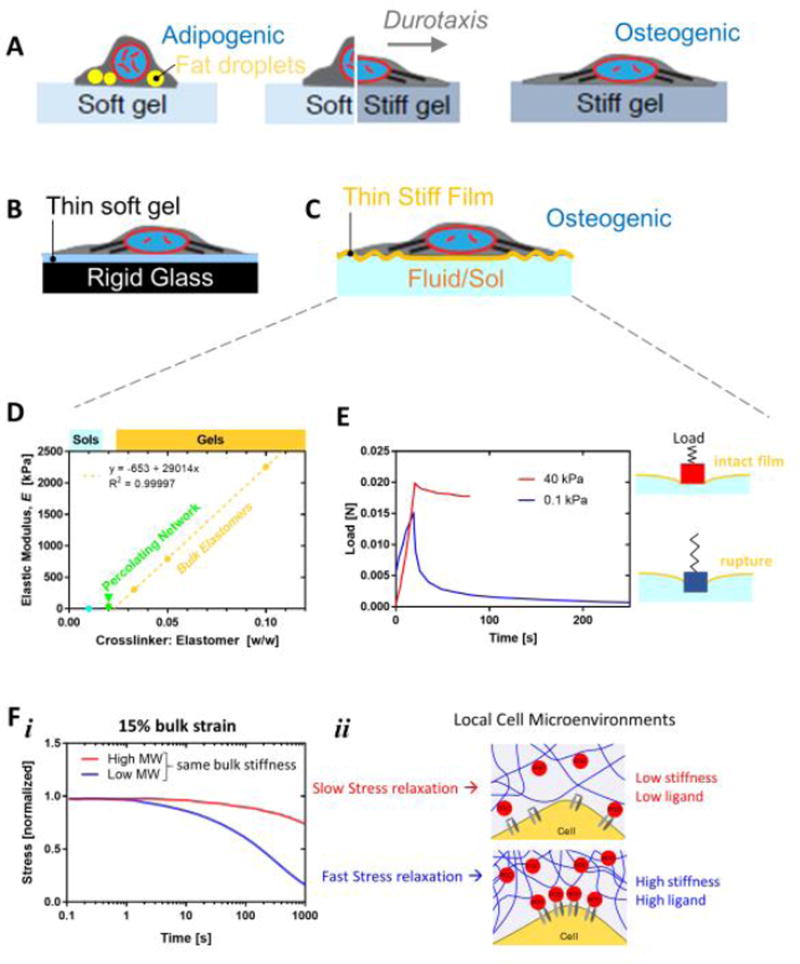

Figure 2. Heterogeneity in matrices can be lateral or vertical and affect stem cell morphology, motility, and niche localization.

A. Thick gels that are soft or stiff can be made with lateral heterogeneity to study processes such as durotaxis. MSCs are rounded and adpiogenic on soft gels, strongly spread and filled with stress fibers on osteogenic-favoring stiff gels, and directionally polarized on gels with a stiffness gradient.

B, C. Stratified materials can be laterally homogeneous and preserve adhesive ligand chemistry and density but still favor spreading and osteogenesis of MSCs. Underlying rigidity can be mechanosensed and a stiff layer can obscure underlying softness or fluidity.

D, E. Analysis of reported elastic modulus versus crosslinker content can sometimes indicate polymerization conditions insufficient for bulk gelation (data from [39]). Re-plot of the mechanical measurements reveals an instability in the softest material reported as “0.1 kPa”. The peak and decay in the load or force when this latter material is indented to a constant level is largely absent for a stiff gel, and the peak likely indicates sudden rupture through a film. The film is stiff because it initially gives a similar magnitude force peak as the stiffer material, but the subsequent force decay over tens of seconds indicates viscous losses into a fluid.

F. The stress relaxation and viscous component of a hydrogel can be modified by adjusting polymer length and interactions independent of bulk elastic stiffness. Various molecular weight chains of agarose have been coupled to a PEG spacer to control the gel relaxation time from 60–2,300 seconds under constant strain. The viscous component allows for matrix malleability but also heterogeneity: