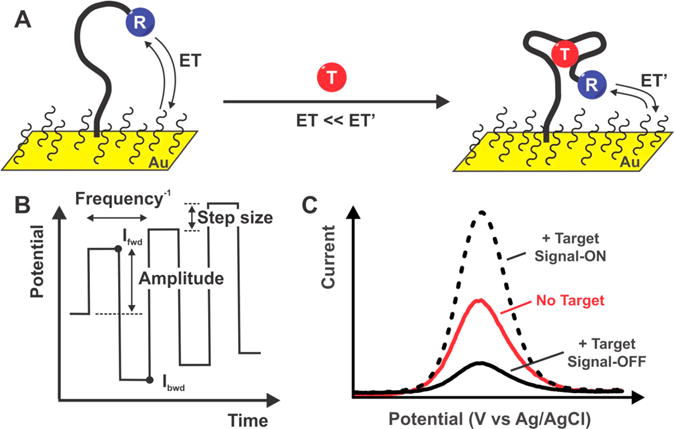

Figure 1.

(A) E-DNA sensors detect their target analytes (“T”) via a binding-induced conformational change in their DNA probes. This alters the rate of electron transfer (ET vs ET′) from an attached redox reporter (“R”). (B) Square-wave voltammetry is typically employed to convert this change in electron transfer rates into a change in observed current. In this technique, we apply a rising, “staircase” potential waveform and measure the Faradaic current at the end of each square pulse. A voltammogram (current versus potential) is generated from this by taking the difference between each subsequently measured current (Ifwd − Ibck). Because of this sampling protocol, square-wave voltammetry can be “tuned” to be more or less sensitive to specific electron transfer rates. For example, it is relatively insensitive to transfer reactions that are much more rapid than the square-wave frequency because the Faradaic current from such a reaction will have decade to near zero before the current is measured as the end of the pulse. (C) This signal gain of E-DNA sensors (the relative signal change seen upon the addition of saturating target) is a strong function of square-wave frequency. Indeed, many E-DNA sensors can be switched from “signal-on” behavior (positive gain, in which binding causes an increase in current) to “signal-off” behavior (negative gain) simply by altering the square-wave frequency. Here, we explore the extent to which the square-wave frequency dependence of E-DNA signal gain is also a function of the amplitude (and other parameters) of the square-wave pulse.