Abstract

Introduction:

High incidence rates of childhood cancer and the consequent deaths in the Middle East is one of the major reasons for the need for palliative care in these countries. Using the experiences and innovations of the other countries can provide a pattern for the countries of the region and lead to the development of palliative care in children. Therefore, the aim of this study is to compare the status of pediatric palliative care in Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, and Iran.

Materials and Methods:

This is a comparative study in which the information related to pediatric palliative care system in the target countries (from 2000 to 2016) has been collected, summarized, and classified by searching in databases, such as “PubMed, Scopus, Google scholar, Ovid, and science direct.”

Results:

Palliative care in children in the Middle East is still in its early stages and there are many obstacles to its development, namely, lack of professional knowledge, inadequate support of policy-makers, and lack of access to opioids and financial resources. Despite these challenges, providing services at the community level, support of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), using trained specialists and multi-disciplinary approach is an opportunity in some countries.

Conclusion:

Considering the necessity of the development of pediatric palliative care in the region, solutions such as training the human resources, integrating palliative care programs into the curriculum of the related fields, establishing facilitating policies in prescription and accessibility of opioids, providing the necessary support by policy-makers, doing research on assessment of palliative care quality, as well as NGOs' participation and public education are suggested.

Keywords: Cancer, children, comparative, Middle East, palliative care, system

INTRODUCTION

Childhood cancer often occurs before the age of 15 and comprises 0.5% of all cancers combined, and its incidence rate is between 50 and 200 cases/1,000,000 worldwide.[1] About 80%–85% of such cases occur in developing and less developed countries due to their large youth population.[2] Despite successful treatment of 80% of children with cancer in developed countries, this figure is only 20% in developing countries[3] and this is due to some factors, such as late diagnosis, lack of access to health-care facilities, limited financial resources, population increase, and poverty.[4] In such circumstances where there is no cure, the need for palliative care becomes necessary.[5]

Palliative care in children is a response to their physical, mental, social, and spiritual needs with the aim of improving the quality of life for the children and their families. It starts with the diagnosis, and can be applied regardless of whether or not the patients received the treatment.[3,6]

According to an estimate by Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life, 1/2 million children in the world need end of life care, 98% of which are in developing and less developed countries.[7,8] Furthermore, due to the high rate of cancer in children, provision of these services are considered to be a necessity in the Middle East[9,10] and the establishment of palliative care in children, and education of pediatric oncologists, pain specialists, and nurses are among the priorities of the Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC).[9] The ranking of palliative care in children shows that 65.5% of the countries in the world, most of which are developing and underdeveloped, are in level 1; that is, no services are offered.[7]

In addition in Asia, among 47 countries, 66% also lack this system, and only 2% enjoy this system completely.[11]

However, due to establishment of MECC, there has been great improvement in providing cancer patients with services in the Middle East in recent years; the progress of nations in palliative care ranking in the world is an evidence supporting the claim.[12] However, lack of research on pediatric palliative care has been one of the reasons for its slow development in the Middle East.[13] Accordingly, identifying different kinds of pediatric palliative care system in the Middle East, applying the other countries' experiences and innovations, and determining the degree of success in achieving the standards of palliative care through quality evaluation index can help establishing and developing this care system in countries of the region.[3,14]

Offering a palliative care system requires a proper structure in which caregiving processes are available, and the effectiveness of the services provided can be assessed according to the outcomes of palliative care system. The quality evaluation index also examines this system in terms of three indices, namely, structure, process, and outcome.[15] Structure includes different settings such as hospital, hospice, clinic, home care services, and the personnel of such settings, including doctors, nurses, psychologists, as well as infrastructures such as equipment and information sites. Moreover, services provided in these settings are referred to as palliative cares, which include care in physical, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects for the patients and their families, education of human forces, research, provision of financial resources, etc. Moreover, the final factor is the outcomes of these services which are measured through such factors as life quality, satisfaction survey, cost-effectiveness.[15,16] Since a proper planning requires identification of the tasks performed and the existing gaps unfilled for future success,[17] this study aimed to describe and compare the structure and process of palliative cares in children with cancer was carried out in five countries, including Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, and Iran so that it can offer some solutions for providing such services in the Middle East region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a comparative study in which the information related to palliative care system in children with cancer in the target countries (from 2000 to 2016) has been collected, summarized, and classified into two major categories, including structure and process using library method and searching the data bases, such as PubMed, Scopus, Science direct, Google scholar, Ovid, Cinahl by keywords such as palliative care, pediatric, cancer, system, health care, hospice, and Middle East.

The study population included Turkey, Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, and Iran. Although these countries enjoy similar structures in their health system and sociocultural and economic patterns; they have been ranked differently in palliative care system. Since access to care services in the countries with limited resources is considered as a big challenge, this study has compared different structures of these five countries in terms of their settings in providing services and their human resources,[18] and their different processes in terms of such factors as different dimensions of care (physical, psychological, social, and spiritual), workforce training, supply of opioids, and financial resources.[16]

On outcomes, no comparison was made. It was due to the fact that the palliative care system was quite young in the target countries and there was little information on evaluating care outcomes.

Demographic information

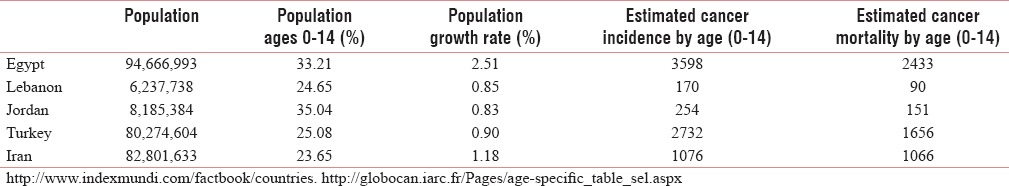

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in Jordan, Egypt, and Lebanon. It is considered the third cause of death in Iran and the fourth cause of death in Turkey. The most common types of cancer in Egypt, Lebanon, and Iran are leukemia, brain tumor, and lymphoma, respectively. In Jordan, leukemia, brain tumor, skeletal, and soft tissue tumor in girls and lymphoma in boys are the most frequent cancers. Moreover in Turkey, leukemia, lymphoma, and brain tumor are considered as the most common ones Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information

The structure of providing palliative care

This section includes the history of pediatric palliative care, the setting of providing such services and the human resources in the target countries.

Egypt

The National Cancer Institute, Cairo University as the largest comprehensive cancer center launched the first palliative care service[19] on an outpatient basis for children with cancer in a 100-bed hospital in Cairo in late 2007 and in 2010, home care program was also added to it.[20,21] Furthermore, Foka charity in rural areas of Egypt provides level 1 and level 3 (combined) services to children with cancer.[22] These services are offered by a multidisciplinary team, including a specialist consultant on pediatric palliative care, two pediatric oncologists, pain management service, two specialist nurses, a cancer psychologist, and a social worker. Home care service is managed by a doctor and a nurse.[21]

Lebanon

In 2002, the first Children's Cancer Hospital was established in Lebanon and then, pediatric oncology units were developed in various hospitals. There were 10 oncology units by 2010. Palliative care services for children are carried out in these units and there is no specialized unit for this purpose. Home-care, as one of the settings providing services, is also available but limited in the country. Services are provided by oncologists, staff, volunteers, and social workers.[23,24]

Jordan

The first children's palliative care service was founded in 2005 at King Hussein Cancer Center in Amman. The available settings for palliative care in Jordan include out-patient, in-patient, and home care. It is managed by phone 24/7 (24 h a day and 7 days a week). The services are provided by full-time members, including a pediatric oncologist, a pediatrician, two palliative care specialist nurses, and parents. In addition, a psychologist, a social worker, and a pharmacologist also cooperate on a part-time basis.[25,26]

Turkey

In Turkey, it all started from 2010. However, giving modern services to children with cancer dates back to 1970 when pediatric oncology and hematology was recognized as an independent specialty, and the specialists do their treatment based on National and International guidelines. In 2011, in DUZKY hospital in Izmir, palliative care for children was offered in an in- and out-patient setting. Although palliative care for children with cancer was being offered before 2011, this hospital – now supported by international organizations – gives its services as a standard palliative care unit. Most of these services are provided by the doctors and the nurses who have experienced working in pediatric oncology unit, or received palliative care certificate. There are a few social workers, psychologists, and art therapists in this unit as well.[27,28,29,30]

Iran

There is no pediatric palliative care setting in Iran, and only the oncology units provide such services in the country. These divisions are managed by oncologists, nurses, social workers, and psychologists. As of 2010, there were 65 pediatric oncologists, in the country, working in 26 medical hospitals.[31]

Palliative care processes

Palliative care includes processes in which care is given (in its all possible dimensions) to the patients. They start with cancer diagnosis and end with the bereavement care after death.[16] In this study, dimensions of palliative care based on the guidelines, human resources training, and supplying opioids and financial resources are examined.

Egypt

In Egypt, after communicating with patients and their families, trained specialists provide the multidisciplinary care with respect to patients' physical, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions. There are national guidelines for management of acute and chronic pain and other symptoms in the country. Recently, end-of-life care, as well as hospice and home care guidelines, have also been formulated, but there is no guideline for pediatric palliative care yet.[20,32,33]

Lebanon

After communicating with the patients and their families, the disease is explained in plain language, and the medical decisions are made. Care, in Lebanon, begins with pain management. Currently, physical, psychological, social, and end-of-life care are also provided, in a multidisciplinary way.[24,34]

Jordan

In Jordan, the patients are first referred to the cancer center by the oncologist. The multidisciplinary care is provided according to the patient's choice either in hospitals or in their house meeting their physical, spiritual, psychological, and social needs. Bereavement care is also offered to support the child's family.[29,35]

Turkey

Until 2005, care services in Turkey were only limited to physical care and pain management. Now, physical, psychological, and social care is performed by a multidisciplinary team.[27,30]

Iran

Palliative care for adults is provided by a multidisciplinary team. However, due to lack of knowledge and expertise, palliative care is not so much known, and interdisciplinary approach is known as a gap in Iran. On children, there is no reliable information; and only in MAHAK hospital, pain relief is done for children with cancer.[36,37,38]

Human resources training

Training specialized forces is one of the important challenges in all these countries.[33] Currently, East Mediterranean Region Office in the World Health Organization (WHO) and MECC have considered training programs for improving palliative care services as one of the main objectives in the region.[9] Furthermore, some countries have independently communicated with some of the most important foreign centers providing palliative care to train their manpower.

In Egypt, the National Cancer Institute is active in palliative care training and has included this subject in the curriculum of nursing students. It also offers pain management at master (postgraduate) degree and basic palliative care courses annually. Other programs include training the Egyptian nurses in the UK in collaboration with the European Society for Medical Oncology. Although this concept is included in the postgraduate nursing curriculum, the creation of an independent discipline and its integration into nursing and medical curriculum is necessary.[19,32]

Furthermore in Lebanon, training palliative care began with communicating with the WHO. In 2010, 9 fellows from different Lebanese universities were sent to end-of-life care training to America. After they returned, a workshop on their success in the management of hospitals, challenges and ways to integrate palliative care in nursing and medical curriculum was held. Currently, 21 h of training are included in the curriculum of nursing and medical students. Short-term training courses on end-of-life care are also offered in Lebanon. Palliative care fellowship has also been designed but not implemented yet. Community education is also performed actively by Governmental organizations and Hospice SAND center.[24,39,40,41]

In Jordan, palliative care society was established in 2010 with the aim of promoting awareness and education, and training the experts. Currently, this subject is an optional course in the nursing curriculum in some universities in Jordan. Recently, a postgraduate palliative care program is run in Nursing School of Jordan University, and a pain management course is also presented in German Jordanian University. Palliative care and hospice fellowship course are also on the priority list. Running these courses, in an ongoing basis, in Malik Hussein Hospital is an example. In the mentioned hospital, a short-course is run for the new personnel and is repeated annually to keep the personnel updated.[25,42,43]

In Turkey, palliative care training is offered in some universities for nursing students. In this training, a 14-week course with the duration of 28–56 h is run. Some seminars, conferences and workshops are also held in Turkey. The first workshop, with the aim of creating a model of palliative care, was held 3 times in Ankara in 2008. After that, this workshop is still being held both Nationally and Internationally. The last meeting was held in February 2017 with the aim of presenting evidence-based care in cancer palliative care. In total, 434 people in Turkey had been trained in palliative care by 2014.[27,44]

In Iran, palliative care fellowship program is offered in Tehran University. In addition, it is included in the nursing curriculum for 2–32 h sessions. This program has been proposed as an independent discipline. However, development of a multidisciplinary curriculum in cancer is also underway. Furthermore, seminars, conferences, and workshops are also held. 30 clinical nurses passed an introductory training course on palliative care in Turkey in 2012. Then, they trained the other nurses in Tehran. They managed to hold 6 training workshops by 2015.[45,46]

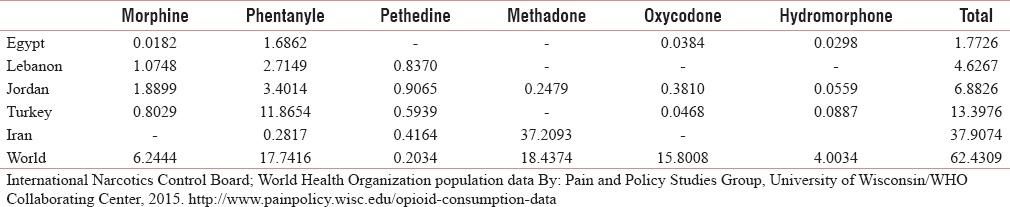

Availability of opioids

Since the use of opioids, especially morphine can be considered as an indicator of the need for palliative care; therefore, these five countries have also been compared with each other regarding such an important factor. In the world ranking in 2010, Turkey with the hiest consumption was fourth in Asia, and Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt and Iran ranked 10th, 11th, and 24th respectively. Based on statistics published by International Narcotics Control Board in 2014, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and Egypt have had the highest consumption of morphine, respectively. However, compared with global consumption, morphine consumption in these countries is low (6/28). However, Iran and Turkey have had a high consumption of other opiates. (methadone in Iran and fentanyl in Turkey) Table 2.[47,48,49]

Table 2.

Opioid consumption

Financial resources

In Egypt, most services are governmental, and treatment costs are paid by health insurance. Charity institutions are also active in Egypt.[29,50] In Lebanon, patients' costs are paid by insurance; in addition, three large charity institutions give their services free of charge in many hospitals.[24,40] In Jordan, Jordanian citizens can use health services freely and enjoy governmental and private insurance. Patients can also use free services of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) when necessary.[29,42] In Turkey, except health-care system which is provided by the government, private insurances plays a limited role. A few NGOs are also involved in that country.[29] In Iran, in addition to governmental and private insurance, NGOs are also active and help the patients pay nearly all medical expenses. MAHAK children's hospital is an example of such NGOs.[37]

DISCUSSION

High incidence rates of childhood cancer and the consequent deaths in the Middle East is one of the major reasons for the need for palliative care in these countries. Using the experiences of the other countries which have similar political, economic, and social status can provide a pattern for the countries of the region and lead to the development of palliative care in children.[10] Therefore, this study aimed to compare palliative care status in children in the selected countries.

Palliative care in children in the Middle East is still in its early stages and there are many obstacles to its development, namely, lack of professional knowledge, inadequate support of policy-makers, and lack of access to opioids and financial resources.[21,51] Despite these challenges, results of this study showed that Jordan, due to the availability of various settings, had a desirable condition compared to the other countries. Having overcome the existing obstacles, Jordan managed to improve its position in palliative care ranking in the world.[7,52] Conversely, Iran has no formal structure for providing such services, and due to the lack of evidence in need assessment, policymakers of the country are not aware of the necessity and priority of these services.[53] Furthermore, due to the importance of health structures,[17] there are a variety of care settings in every country. The most common structure is hospital-based clinics which are available in some countries such as Jordan, Egypt, and Turkey. According to the recommendation of the WHO, it is the best setting for countries with limited financial resources, especially when combined with hospital consulting.[51] Also in Iran, for the development of palliative care, this model has been chosen as a priority in adults with cancer.[54] However, to provide all children with access to palliative care services, WHO has emphasized availability of such services at community level including at patients' homes.[9,51] Home-care is one of the most desirable models of palliative care which is given to the patients and their families by a team consisting of doctors, nurses, and volunteers. This service is available in Lebanon, Egypt and Jordan. Lebanon is in a very early stage and because of some experts' belief in its impact on reducing the burden of care level 3, it has been offered on a limited basis.[23] Furthermore in Iran, due to positive attitude of policy makers toward development of homecare and its economic and social benefits for the patients, their families and the health-care system, it has been considered as one of the important requirements of the country's health system and is offered to adults with cancer, on a limited basis.[55,56] Moreover finally, the specialist palliative care unit in hospitals, as the most comprehensive setting, is only available in Jordan. Its introduction as the most advanced country in palliative care in the Middle East in 2006 is an evidence of the claim[9,52] and it is due to some reasons, namely, provision of services at different levels, support of NGOs, support of the government, and development of professional and general education.[35,42,51] It seems that in countries with limited resources, lack of financial information on different models of care is one of the important factors in the development of palliative care for children.[57]

In addition to providing appropriate settings for palliative care services, provision of human resources, depending on the model of the service, is also important and essential.[51] With regard to multidisciplinary approach, availability of various specialties can be an indicator of its development in the countries, and Jordan is an example of that.[25] According to the results of a research done by Knapp and Thompsonadopting a multidisciplinary approach and arranging a team of professionals, including psychologist, social workers, and child life specialists is an important strategy in overcoming the reluctance of families as the biggest obstacle toward receiving palliative care.[58]

Accordingly, it is obvious that optimal implementation of palliative care (provision of care-giving process) requires knowledge and awareness of service providers which is considered to be a major challenge in the region.[41] The results of the studies in Lebanon and Iran confirmed that the knowledge of doctors and nurses, despite holding periodic training for them, is low on the issue.[34,59] Lack of attention to this subject in the curriculums is one of the reasons for this unawareness.[31,45] Conversely, Jordan uses trained people and professionals, other than doctors and nurses, to give palliative care. These professionals include psychologists, nutritionists, social workers, and pharmacologists. Moreover, this is another reason for development of such services in the country.[25] In spite of the American Academy of Pediatrics' emphasis on the need for basic competence in palliative care, only 39% of professionals have the necessary knowledge.[60] Since knowledge and attitude of doctors as the patient's first gate of palliative care is very important,[53] its integration into the medical and nursing curriculum is highly recommended.[25,27,32,45] Currently, one of the biggest obstacles is the lack of professors that can be problematic in the future.[53] In such circumstances, using nonformal methods of education such as seminars and workshops can be effective, and countries have realized its importance as a short-term solution. Therefore, they seek to take advantage of international experts. Their attempt toward international communication is an indication of such an approach.[61] In addition, increasing public awareness to overcome cultural and social barriers as well as misconceptions about palliative care is necessary.[51,62] Jordan has been rather successful in removing such barriers to develop its palliative care system.[52]

Furthermore, use of care guidelines is another requirement of providing such services. According to the results of a study done on adults with cancer in Lebanon, despite improvement of their quality of life, the patients were still dissatisfied with the way the symptoms were managed. Therefore, they called for its improvement.[63] To solve such problems, there is a need for guidelines of palliative care. In every country, these guidelines have been determined based on resources, principles, and objectives of the country's health system.[3] Development of such guidelines requires evidence of effectiveness of the interventions. The effectiveness of palliative care can be shown by evaluating its outcomes in terms of cost-effectiveness, quality of life, and satisfaction.[15,64] Although it seems that availability of guidelines is not enough for symptom management. As an example, one of the most common and challenging symptoms is pain. Despite availability of relevant guidelines, pain management continues to be a major challenge in these countries.[10] Lower consumption of opioids and low estimation of the need for morphine in the countries of the region compared to developed countries is indicative of this fact.[65] Despite having pain clinics, specialist personnel and a history of over 15 years, Egypt still ranks low in providing palliative care in the region. However, Jordan has a better position in the area; and the increase in opioid consumption indicates pain relief and development of palliative care system of the country.[7] According to the International Narcotics Control Board report, the most common opioids used for relieving pain in the world are fentanyl, morphine, and oxycodone.[48] It is interesting that despite high consumption of oxycodone in the world, its consumption is low in these areas.

In all the countries under the study, factors such as fear of addiction, restrictive rules on prescribing medicine, and knowledge and attitude of health-care providers are among the most important obstacles in controlling pain.[66] In Lebanon, economic problems are also added to this list.[24] In Iran, in addition to the factors mentioned, lack of insurance coverage on the one hand, and cultural and religious barriers, on the other hand, can add to the complexity of this issue.[33,67] To overcome the obstacles, general and professional education, and easy access to opioids can be effective.[9,33,36]

Considering the existing obstacles and the need for palliative care in the Middle East and challenges of all these countries in provision and allocation of resources, as well as the WHO's emphasis on its integration into the health system, using NGOs can be very helpful.[51] Almost all countries have such experience. In Iran, these NGOs are very active in giving palliative care to adults, and their capacity can be used to provide palliative care to children as well.[59] Furthermore, confirming the cost effectiveness of these services through conducting research can help to convince policymakers to allocate financial resources.[54]

Finally, considering the percentage of young population, rate of population growth, cause of death, and development of palliative care in the target countries, it can be said that establishment of pediatric palliative care is essential, and it is hoped that the results of this comparison serves as a model for countries of the region. Therefore, the major solutions which can be suggested for developing palliative care in the region include education of human resources, and integration of palliative care into the curriculum of the relevant disciplines. Furthermore, adopting facilitative policies in prescribing opioids and providing access to them, support of policymakers, doing research in the field of assessing the quality of palliative care, and participation of NGOs can help to develop this care system.

Moreover at the end, we recommend an integrated model of palliative care to the countries' health-care system in combined with other mentioned strategies. In addition, as the accessibility to such a services is strongly recommended the WHO, it is proposed to categorize palliative care services to the first, propose second, and third level, which their administration are being facilitated using potentials of NGO organizations in providing financial support to recruitment and train human resource as the main prerequisites.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study is part of a doctoral nursing dissertation of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Dr. Kazem zendehdel for guiding and assistingduring the preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. [Last accessed on 2017 Mar 04]. Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/media/news/Childhood_cancer_day/en/

- 2.White Y, Castle VP, Haig A. Pediatric oncology in developing countries: Challenges and solutions. J Pediatr. 2013;162:1090–1. 1091.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caruso Brown AE, Howard SC, Baker JN, Ribeiro RC, Lam CG. Reported availability and gaps of pediatric palliative care in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of published data. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:1369–83. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magrath I, Steliarova-Foucher E, Epelman S, Ribeiro RC, Harif M, Li CK, et al. Paediatric cancer in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e104–16. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Mechelen W, Aertgeerts B, De Ceulaer K, Thoonsen B, Vermandere M, Warmenhoven F, et al. Defining the palliative care patient: A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2013;27:197–208. doi: 10.1177/0269216311435268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amery JM, Rose CJ, Holmes J, Nguyen J, Byarugaba C. The beginnings of children's palliative care in Africa: Evaluation of a children's palliative care service in Africa. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:1015–21. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connor SR, Sepulveda Bermedo MC. Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life: The Open Society Foundations': International Palliative Care Initiative; Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance. 2014:111. ISBN: 978-0-9928277-0-0. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Cancer control: Knowledge into action. WHO Guide for Effective Programmes: Module 5: Palliative Care. 2007. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 16]. Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/media/FINAL-PalliativeCareModule.pdf . [PubMed]

- 9.Silbermann M, Al-Hadad S, Ashraf S, Hessissen L, Madani A, Noun P, et al. MECC regional initiative in pediatric palliative care: Middle Eastern course on pain management. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34(Suppl 1):S1–11. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318249aa98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silbermann M, Fink RM, Min SJ, Mancuso MP, Brant J, Hajjar R, et al. Evaluating palliative care needs in middle Eastern countries. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:18–25. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherny N, Fallon M, Kaasa S, Portenoy R, Currow D. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. 5th ed. England: Oxford University Press; 2005. p. 1504. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynch T, Connor S, Clark D. Mapping levels of palliative care development: A global update. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:1094–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downing J, Knapp C, Muckaden MA, Fowler-Kerry S, Marston J. ICPCN Scientific Committee et al. Priorities for global research into children's palliative care: Results of an International Delphi Study. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:36. doi: 10.1186/s12904-015-0031-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadeghi A, Barati O, Bastani P, Jafari DD, Etemadian M. Experiences of selected countries in the use of public-private partnership in hospital services provision. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66:1401–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woitha K, Van Beek K, Ahmed N, Hasselaar J, Mollard JM, Colombet I, et al. Development of a set of process and structure indicators for palliative care: The Europall project. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:381. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancer Research Center. Development of a Comprehensive National Program for Palliative and Supportive Cancer Care Project. Cancer Research Center. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams AM, Crooks VA, Whitfield K, Kelley ML, Richards JL, DeMiglio L, et al. Tracking the evolution of hospice palliative care in Canada: A comparative case study analysis of seven provinces. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:147. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shamieh O, Jazieh AR. MENA Cancer Palliative Care Regional Guidelines Committee. Modification and implementation of NCCN guidelines on palliative care in the Middle East and North Africa region. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(Suppl 3):S41–7. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Ansary M, Nejmi N, Rizkallah R, Shibani M, Namisango E, Mwangi-Powell F, et al. Palliative care research in Northern Africa. Eur J Palliat Care. 2014;21:98–100. [Google Scholar]

- 20.ElShami M. Palliative care: Concepts, needs, and challenges: Perspectives on the experience at the children's cancer hospital in Egypt. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(Suppl 1):S54–5. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3182122035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knapp C, Madden V, Fowler-Kerry S. Pediatric Palliative Care: Global Perspectives. London, New York: Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egypt's Fakkous Center. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 19]. Available from: http://www.egyptcancernetwork.org/about/our-partners/fakkous/

- 23.Abboud M, Azzi M, Muwakkit S. Pediatric palliative care at the children's Cancer center of Lebanon: 2 case reports. Med Princ Pract. 2007;16(Suppl 1):50–2. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noun P, Djambas-Khayat C. Current status of pediatric hematology/oncology and palliative care in Lebanon: A physician's perspective. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34(Suppl 1):S26–7. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318249ad1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Omran S, Obeidat R. Palliative care nursing in Jordan. J Palliat Care Med. 2015;S4:1. doi.org/10.4172/2165-7386.1000S4-005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.King Hossein Cancer Center. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 27]. Available from: http://www.khcc.jo/section/clinical-services-and-departments .

- 27.Can G. The implementation and advancement of palliative care nursing in Turkey. J Palliat Care Med. 2015;5:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mutafoglu K. DEU Palliative Care Strategy Group. A palliative care initiative in Dokuz Eylul university hospital. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(Suppl 1):S73–6. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318212245d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bingley A, Clark D. A comparative review of palliative care development in six countries represented by the Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC) J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:287–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kebudi R. Turkish Pediatric Oncology Group. Pediatric oncology in Turkey. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34(Suppl 1):S12–4. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318249aaac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Discipline. 2010. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 22]. Available from: http://www.aac-hospital.com/files/khoon.pdf .

- 32.Elshamy K. Current status of palliative care nursing in Egypt: Clinical implementation, education and research. J Palliat Care Med. 2015;5:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silbermann M, Arnaout M, Daher M, Nestoros S, Pitsillides B, Charalambous H, et al. Palliative Cancer Care in Middle Eastern Countries: Accomplishments and Challenges†. Annals of Oncology. 2012;23(Suppl 3):15–28. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds084. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abu-Saad Huijer H. Pediatric palliative care. State of the art. J Med Liban. 2008;56:86–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdel-Razeq H, Attiga F, Mansour A. Cancer care in Jordan. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2015;8:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rassouli M, Sajjadi M. Palliative Care to the Cancer Patient: The Middle East as a Model for Emerging Countries. USA: Nova Science Publishers; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pain Department. [Last accessed on 2016 Oct 23]. Available from: http://www.mahak-charity.org/main/index.php/fa/mahak-products/mahak-parts/hospital/parts .

- 38.Rouhollahi MR, Saghafinia M, Zandehdel K, Motlagh AG, Kazemian A, Mohagheghi MA, et al. Assessment of a hospital palliative care unit (HPCU) for cancer patients; A conceptual framework. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:317–27. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.164901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daher M, Doumit M, Hajjar R, Hamra R, Naifeh Khoury M, Tohmé A, et al. Integrating palliative care into health education in Lebanon. J Med Liban. 2013;61:191–8. doi: 10.12816/0001457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daher M, Estephan E, Abu-Saad Huijer H, Naja Z. Implementation of palliative care in Lebanon: Past, present, and future. J Med Liban. 2008;56:70–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The Home Hospice Organization of Lebanon. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 21]. Available from: http://www.sanadhospice.org/about.php#/About%20SANAD .

- 42.Al-Rimawi HS. Pediatric oncology situation analysis (Jordan) J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34(Suppl 1):S15–8. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318249aac1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jordan Palliative Care. [Last accessed on 2016 Oct 08]. Available from: http://www.ehospice.com/Default/tabid/10686/ArticleId/18333 .

- 44.The 4th National & 1st International Oncology Nursing Consensus. Evidence-Based Palliative Care for Cancer Patients. 2017. [Last accessed on 2017 Feb 14]. Available from: http://www.konsensus2017.com/english.html .

- 45.Sajjadi M, Rassouli M, Khanali-Mojen L. Nursing education in palliative care in Iran. J Palliat Care Med. 2015;4:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palliative Medicine Curriculum. 2009. [Last accessed on 2016 Aug 15]. Available from: http://www.iranesthesia.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Curriculum-PalMed.pdf .

- 47.International Narcotics Control Board. Report of the International Narcotics Control Board on the Availability of Internationally Controlled Drugs: Ensuring Adequate Access for Medical and Scientific Purposes. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 48.International Narcotics Control Board. Chapter II. Narcotic Drugs. 2014. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.incb.org/documents/Publications/AnnualReports/AR2015/English/Supp/AR15_Availability_E_Chapter_II.pdf .

- 49.Pain and Policy Studies Group. 2014. [Last accessd on 2016 Sep 30]. Available from: http://www.painpolicy.wisc.edu/countryprofiles .

- 50.Hablas A. Palliative care in Egypt: Challenges and opportunities. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(Suppl 1):S52–3. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318212201e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.World Health Organization. Planning and Implementing Palliative Care Services: A Guide for Programme Managers. World Health Organization. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stjernswärd J, Ferris FD, Khleif SN, Jamous W, Treish IM, Milhem M, et al. Jordan palliative care initiative: A WHO demonstration project. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:628–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knapp CA. Research in pediatric palliative care: Closing the gap between what is and is not known. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2009;26:392–8. doi: 10.1177/1049909109345147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khoobin Khoshnazar TS. Service Packs on Breast Cancer. School of Nursing and Midwifery. Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barati A, Janati A, Tourani S, Khalesi N, Gholizadeh M. Iranian professional's perception about advantages of developing home health care system in Iran. Hakim Res J. 2010;13:71–9. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hosoya S, Shahriari S, Taleghani F. Necessity of spiritual care for end-stage cancer patients and their families in Iran: From the analysis of practice in a home-visit organisation in Isfahan. The APM Supportive and Palliative Care Conference. [Last accessed on 2017 May 16];BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Knapp CA, Thompson LA, Vogel WB, Madden VL, Shenkman EA. Developing a pediatric palliative care program: Addressing the lack of baseline expenditure information. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2009;26:40–6. doi: 10.1177/1049909108327025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knapp C, Thompson L. Factors associated with perceived barriers to pediatric palliative care: A survey of pediatricians in florida and California. Palliat Med. 2012;26:268–74. doi: 10.1177/0269216311409085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rassouli M, Sajjadi M. Palliative care in Iran: Moving toward the development of palliative care for cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33:240–4. doi: 10.1177/1049909114561856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barnett MD, Maurer SH, Wood GJ. Pediatric palliative care pilot curriculum: Impact of “Pain cards” on resident education. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33:829–33. doi: 10.1177/1049909115590965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alfa Cure Center. ESMO Designated Centre of Integrated Oncology and Palliative Care. [Last accessed on 2016 Oct 05]. Available from: http://www.esmo.org/Patients/Designated-Centres-of-Integrated-Oncology-and-Palliative-Care/Alfa-Cure-Center-Egypt .

- 62.World Health Organization. Barriers to Palliative Care. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 27]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs402/en/

- 63.Abu-Saad Huijer H, Doumit M, Abboud S, Dimassi H. Quality of palliative care. Perspective of lebanese patients with cancer. J Med Liban. 2012;60:91–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Knapp C, Madden V. Conducting outcomes research in pediatric palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27:277–81. doi: 10.1177/1049909110364019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.International Narcotics Control Board. Estimated World Requirements of Narcotic Drugs in Grams for 2016. 2016. [Last accessed on 2016 Oct 02]. Available from: https://www.google.com/url?url=https://www.incb.org/documents/Narcotic-Drugs/Status-of-Estimates/2016/EstJul16.pdf&rct=j&frm=1&q=&esrc=s&sa=U&ved=0ahUKEwiAObOoc_SAhWM6xQKHSYfCI4QFggTMAA&sig2=ILZ0QqmIUg1aHsjZjXESEQ&usg=AFQjCNGkFeAO8F7IZaS0Un2Hdy_AkdG9mg .

- 66.Cleary J, Silbermann M, Scholten W, Radbruch L, Torode J, Cherny NI, et al. Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in the Middle East: A report from the global opioid policy initiative (GOPI) Ann Oncol. 2013;24(Suppl 11):xi51–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rassouli M, Sajjadi M. Cancer care in countries in transition: The islamic republic of Iran. In: Silbermann M, editor. Palliative Care in Countries & Societies in Transition. USA: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]