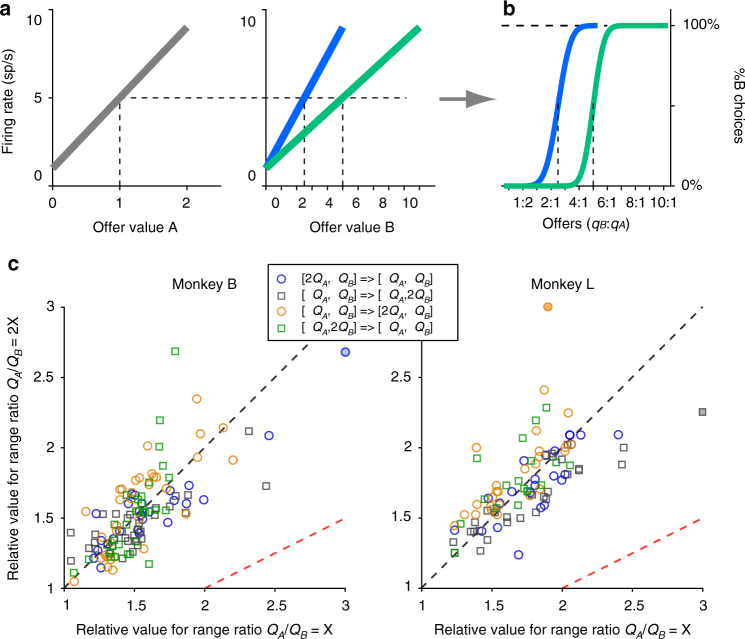

Fig. 3.

Range adaptation is corrected within the decision circuit. a, b Uncorrected range adaptation would induce arbitrary choice biases. Panel a shows the schematic response functions of two neurons encoding the offer value A (left) and the offer value B (right). Panel b shows the resulting choice patterns under the assumption that decisions are made by comparing the firing rates of these two cells. We consider choices in two conditions, with the range ΔA = [0 2] kept constant. When ΔB = [0 5], the firing rate elicited by offer 1 A is between that elicited by offers 2B and 3B (ρ = 2.5). When ΔB = [0 10], offer value B cells adapt to the new value range. Now offer 1 A elicits the same firing rate as offer 5B (ρ = 5). Thus if range adaptation is not corrected, changing either value range induces a choice bias. Importantly, this issue would vanish if both neurons adapted to the same value range. However, experimental evidence indicated that each population of offer value cells adapts to its own value range 9. c Relative values measured in Exp.2. The two panels refer to the two animals. In each panel, the axes represent the relative value measured when Q A/Q B = X (x-axis) and that measured when Q A/Q B = 2X (y-axis). Each data point represents data from one session, and different symbols indicate different protocols (see legend). If decisions were made by comparing uncorrected firing rates, data points would lie along the red dotted line. In contrast, data points lie along the black dotted line (identity line). In other words, the relative values measured in the two trial blocks were generally very similar, indicating that range adaptation was corrected within the decision circuit. Panels a and b are reproduced from9