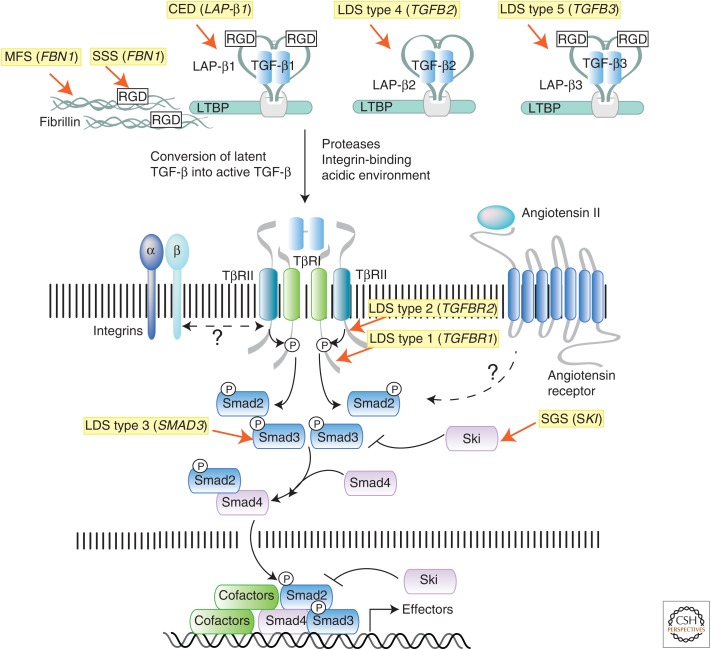

Figure 2.

Summary of the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling pathway and mutations causing connective tissue disorders. TGF-β molecules (TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3) are secreted in latent forms that are unable to interact with the receptors. In the latent form, dimeric TGF-β molecules are noncovalently associated with dimeric latency-associated peptides (LAPs), which are made from the same gene as the corresponding TGF-β molecule. This complex, which is referred to as the small latent complex (SLC), is then covalently linked by disulfide bonds to a member of the latent TGF-β binding protein (LTBP) family, to form the larger complex called large latent complex (LLC). The LLC complex interacts noncovalently with various components of the extrcellular matrix (ECM), including fibrillin microfibrils and integrins, the major adhesion molecule linking cells to the ECM. Both fibrillin and TGF-β (TGF-β1 and -β3, but not TGF-β2) contain an arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) domain that can bind integrin molecules. Cross talk between LTBP, fibrillin, and integrins is thought to be critical for proper localization, sequestration, and conversion of latent TGF-β to active TGF-β. Once activated, dimeric TGF-β binds to a tetrameric receptor complex formed by two type I (TβRI) and type II (TβRII) receptor subunits, leading to direct phosphorylation of R-Smads (Smad2 or Smad3), complex formation with co-Smad (Smad4), and induction or repression of target gene expression. Heterozygous inactivating mutations in both “positive” and “negative” regulators of this pathway have been identified as the cause of genetic disorders that are characterized by pathological alterations in the connective tissue due to misregulated expression of TGF-β gene targets (i.e., tissue metalloproteinases, collagen, integrins, and several other ECM components). The syndromes associated with these mutations, and the human gene mutated in each condition, are highlighted in yellow.