Abstract

In this study, we introduced structure-based rational mutations in the guinea pig leukotriene B4 receptor (gpBLT1) in order to enhance the stabilization of the protein. Elements thought to be unfavorable for the stability of gpBLT1 were extracted based on the stabilization elements established in soluble proteins, determined crystal structures of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), and multiple sequence alignment. The two unfavorable residues His832.67 and Lys883.21, located at helix capping sites, were replaced with Gly (His83Gly2.67 and Lys88Gly3.21). The modified protein containing His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 was highly expressed, solubilized, and purified and exhibited improved thermal stability by 4 °C in comparison with that of the original gpBLT1 construct. Owing to the double mutation, the expression level increased by 6-fold (Bmax=311 pmol/mg) in the membrane fraction of Pichia pastoris. The ligand binding affinity was similar to that of the original gpBLT1 without the mutations. Similar unfavorable residues have been observed at helix capping sites in many other GPCRs; therefore, the replacement of such residues with more favorable residues will improve stabilization of the GPCR structure for the crystallization.

Abbreviations: LTB4, leukotriene B4; GPCR, G-protein coupled receptor; gpBLT1, guinea pig leukotriene B4 receptor; TM helix, transmembrane helix; CPM, 7-diethylamino-3-(4′-maleimidylphenyl)-4-methylcoumarin

Keywords: G-protein-coupled receptor, Leukotriene B4 receptor, Rational design mutation, Amino acid homology, Helix capping, Stabilization

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Point mutations were rationally designed to stabilize LTB4 receptor (BLT1).

-

•

The stability of mutant His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 improved by 5 °C.

-

•

BLT1 expression by P. pastoris was increased 6-fold.

-

•

Mutations were designed to replace unfavorable residues at the helix capping site.

-

•

This method would be useful for the stabilization of the other membrane proteins.

1. Introduction

The leukotriene B4 (LTB4) receptor (BLT1) is a rhodopsin-family G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) expressed on the surface of inflammatory cells [1]. LTB4 is a lipid mediator endogenously biosynthesized from an arachidonic acid found within in the phospholipid nuclear membrane in leukocytes and endothelial cells [1]. In the initial inflammatory response, the LTB4-BLT1 system induces inflammatory cell functions, such as the chemotaxis, activation, and endothelial cell adhesion of leukocytes [1]. LTB4 is involved in various inflammatory diseases, including asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [2], and BLT1 antagonists have been developed as therapeutics for related diseases [3].

In vitro studies and the detailed crystal structures of GPCRs, including BLT1, are indispensable for the functional analysis of GPCRs and the development of novel therapeutics using these targets. However, the low expression and unstable solubilization of integral membrane proteins have blocked research progress in these areas [4]. Furthermore, GPCRs, which function as cellular switching molecules, are highly flexible and can switch between the inactive and active conformations. Various approaches to overcome these challenges have been attempted for structural studies of GPCRs [5]. For example, exhaustive mutation screening and production of chimeric GPCRs bound with soluble stable proteins (e.g., T4 lysozyme or b562RIL) have been used to obtain detergent-tolerant GPCRs with high expression and to improve the conformation of GPCRs for crystallization within a suitable ligand complex and/or a conformationally “locked” antibody complex [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25].

Because the design of stabilized, detergent-solubilized proteins is indispensable for in vitro and structural studies of GPCR, we aimed to define residues thought to destabilize BLT1 and subsequently replace these residues with more favorable residues promoting the overexpression, solubilization, and purification of BLT1 based on the original mutant guinea pig BLT1 (gpBLT1) (dN15/Ser309Ala) [4]. We focused on the helix capping residues and those forming internal hydrogen bonds to establish stabilized mutations suitable for purification and crystallization. We used the structure-based rational design of mutations for the stabilization of gpBLT1 in our previously established overexpression system of the original mutant gpBLT1 (dN15/Ser309Ala) in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris [4]. The double mutations His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 (where superscripts indicate Ballesteros–Weinstein numbering [26]) improved the stabilization of the helix capping sites, increasing thermal stability by 5 °C in the large-scale preparation of the BLT1 membrane fraction and by 4 °C in the purified BLT1 sample. This rational approach may be also applicable for improving the stability of the other GPCRs having unfavorable residues at the expected helix-capping site.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Expression and purification of gpBLT1 mutants

Mutant gpBLT1s were overexpressed by P. pastoris, solubilized by dodecylmaltoside (DDM), and purified in the presence of BIIL260, a BLT1 antagonist, which was kindly donated by Boehringer Ingelheim together with BIIL284 for assay, as described previously [4]. Ligand binding and 7-diethylamino–3-(4′-maleimidylphenyl)–4-methylcoumarin (CPM) assays were performed after removal of BIIL260 bound to the gpBLT1 mutants with Superose-12 gel-filtration (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden), eluted with assay buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 0.02% DDM) or CPM buffer (5 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 0.02% DDM). Total protein concentrations were determined using BCA assays (Thermo Scientific Pierce Protein Biology, Rockford, IL, U.S.A.).

2.2. Ligand binding and thermostability assays

The ligand binding assays with the gpBLT1 expressed membrane fraction were performed as described previously [4]. For measurement of thermal stability using the gpBLT1 membrane fraction, aliquots of membrane fractions from small and large expression cultures (10 and 0.4 μg protein in 10 mL and 1 L culture, respectively) were incubated for 30 min at each temperature and quenched on ice for more than 150 min. [3H]-LTB4 (PerkinElmer, Tokyo, Japan) binding was then measured. In the competitive ligand binding assay for the purified gpBLT1, the following immunoprecipitation method was applied to separate the [3H]-LTB4/BLT1 complex and the unbound [3H]-LTB4 incorporated in DDM micelles. First, 25 ng of purified gpBLT1 was reacted with 0.5 nM [3H]-LTB4 and cold ligands in 100 μL BLT1 binding buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl [pH 7.4], 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 0.02% DDM) at 4 °C for 12 h. The reaction solution was then mixed with 10 μL M2 anti-FLAG antibody agarose gel (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 4 °C for 3 h. Next, the gpBLT1 adsorbed gel was washed twice with 200 μL ice-cold BLT1 binding buffer to remove the unbound ligand, and the washed gel was resuspended in 100 μL BLT1 binding buffer. The gel solution was mixed with 1 mL MicroScinti-20 scintillation cocktail (PerkinElmer), and the amount of bound [3H]-LTB4 was measured on a liquid-scintillation counter (PerkinElmer).

2.3. CPM assay

CPM assays were performed as previously described [27] with some modifications. Before heat treatment, 30 μM CPM was incubated with 6 μM gpBLT1 for 3 h at 4 °C in CPM buffer to form CPM-thiol adducts with CPM-accessible Cys residues in native gpBLT1. The mixture was incubated for 30 min at each temperature and quenched on ice. The fluorescence spectrum was measured at excitation and detection wavelengths of 387 and 463 nm, respectively (the slit width of each filter was 1.5 nm) on a Shimadzu spectrofluorophotometer (RF-5301PC). For the blank, the same procedure was performed for the solution without gpBLT1, and the blank fluorescent intensity was subtracted.

2.4. Amino acid multiple alignments

Amino acid sequences of 274 human rhodopsin-family GPCRs and 28 vertebrate BLT1s were obtained from a protein BLAST search using the Swiss-Prot and nonredundant sequences modes, respectively. All sequences were aligned by ClustalW with manual modifications according to the conserved residues among GPCRs [28].

3. Results

3.1. Mutation design for stabilization

The residues contributing to the instability of gpBLT1 were predicted based on the amino acid homology and crystal structures of GPCRs. In principle, the profiles of ligand binding activities should be sustained by the mutants. We presumed that residues other than the completely conserved residues in the various vertebrate BLT1s would not be directly involved in ligand binding; therefore, completely conserved residues were excluded from the mutation targets. Based on 17 crystal structures, 274 amino acid sequences of human GPCRs, and 28 amino acid sequences of BLT1s in various vertebrates (Fig. 1 and Table S1), we focused on elimination of the unfavorable helix capping sites from gpBLT1 and introduction of hydrogen bonds conserved in GPCRs but lacking in gpBLT1 [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [29], [30]. First, the unfavorable residues in helix capping sites were replaced with more favorable, conserved residues among BLT1s at the C-terminal of the transmembrane helix II (TM-II; His83Gly2.67) and the N-terminal of TM-III (Lys88Gly3.21; Fig. 1A and Table S1). Second, putative hydrogen bonds were introduced by replacing residues that were conserved among GPCRs but not in BLT1 at the N-terminal of TM-II (Ala56Asn2.40; Fig. 1B) [28] and at the putative cholesterol binding site (Leu109Ser3.42 or Leu109Thr3.42; Fig. 1C) [25]. These five selected mutations were introduced in the previous construct of dN15/Ser309Ala gpBLT1 mutant [4] as five single and 18 combinational mutations (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Representative template structure for the mutational designs. The three-dimensional structure of the mutation site of gpBLT1 using the structures of known GPCRs. (A) The capping residues at TM-II and TM-III of β2 adrenergic receptor (PDB id: 2RH1). The corresponding capping residues Lys972.68 and Gly1023.21 are colored in magenta, and Trp993.18 and Cys1063.25 with the disulfide partner Cys191 as the conserved Trp3.18–Xxx–(Phe/Leu)3.20–Gly3.21–(Xxx)3–Cys3.25 sequence motif are colored in cyan. This motif, with the exception of Gly3.21, is conserved in gpBLT1. (B) The conserved hydrophilic residue 2.40 in the adenosine A2A receptor (PDB id: 3REY). Residue 2.40 (Asn42) and the hydrogen bond partners are colored in magenta and cyan, respectively. The main-chain carbonyl group was drawn for Leu37. The hydrogen bond is shown as a dashed line. (C) The putative cholesterol-binding site of the adenosine A2A receptor (PDB id: 3EIY). The corresponding residue 3.42 (Ser94) is colored in magenta. The hydrogen bond partners (with water molecules shown as red balls) are in cyan (Ser472.45, which is conserved among GPCRs, including BLT1, is a hydrophilic residue) and green (Ser903.38, which is not conserved; Table S1).

Table 1.

Specific binding and relative remaining activity in construct screening and T50 after preparative-scale expression.

| Mutant | Specific binding (dpm)a | RAb | T50c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 °C | 40 °C | (%) | (°C) | |

| Ala56Asn2.40 | 9±32 | 20±4 | – | N.D. |

| His83Gly2.67 | 4933±88 | 3332±42 | 68 | N.D. |

| Lys88Gly3.21 | 5327±118 | 3993±71 | 75 | N.D. |

| Leu109Ser3.42 | 2179±274 | 889±92 | 41 | N.D. |

| Leu109Thr3.42 | 3193±232 | 1567±82 | 49 | N.D. |

| Ala56Asn2.40/Leu109Ser3.42 | 42±7 | −20±36 | – | N.D. |

| His83Gly2.67/Leu109Ser3.42 | 4398±207 | 3408±159 | 77 | N.D. |

| Lys88Gly3.21/Leu109Ser3.42 | 3783±148 | 2875±77 | 76 | N.D. |

| Ala56Asn2.40/Leu109Thr3.42 | 28±11 | 15±16 | – | N.D. |

| His83Gly2.67/Leu109Thr3.42 | 4758±207 | 3315±97 | 70 | N.D. |

| Lys88Gly3.21/Leu109Thr3.42 | 4836±278 | 3967±201 | 82 | N.D. |

| Ala56Asn2.40/His83Gly2.67 | 5±30 | 9±13 | – | N.D. |

| Ala56Asn2.40/Lys88Gly3.21 | 63±9 | 44±4 | – | N.D. |

| His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 | 5097±482 | 3987±86 | 78 | 48.6±0.1 |

| Ala56Asn2.40/His83Gly2.67/Leu109Ser3.42 | −2±2 | 1±32 | – | N.D. |

| Ala56Asn2.40/Lys88Gly3.21/Leu109Ser3.42 | 21±30 | −6±37 | – | N.D. |

| His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21/Leu109Ser3.42 | 5473±133 | 5184±290 | 95 | 47.9±0.0 |

| Ala56Asn2.40/His83Gly2.67/Leu109Thr3.42 | 2±10 | 22±16 | – | N.D. |

| Ala56Asn2.40/Lys88Gly3.21/Leu109Thr3.42 | 4±32 | 18±36 | – | N.D. |

| His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21/Leu109Thr3.42 | 4856±114 | 4513±28 | 93 | 48.0±0.2 |

| Ala56Asn2.40/His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 | 65±7 | 51±12 | – | N.D. |

| Ala56Asn2.40/His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21/ | ||||

| Leu109Ser3.42 | 12±7 | −9±8 | – | N.D. |

| Ala56Asn2.40/His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21/ | ||||

| Leu109Thr3.42 | 11±14 | 25±11 | – | N.D. |

| Original (dN15/Ser309Ala) | 2523±75 | 1136±81 | 45 | 43.5±0.5 |

The value is the average specific binding with the standard deviation. The average specific binding was calculated as the difference between the total binding (n=3) and the nonspecific binding (n=2). Total and nonspecific binding were set as the binding activity for 0.5 nM [3H]-LTB4 for each membrane fraction without or with 0.5 μM LTB4 treatment, respectively. The membrane fractions from the small-scale expression experiment were reacted using the same amount (10 μg) of total protein.

The remaining activity (RA, %) is the ratio of the specific binding at 25 °C to that at 40 °C.

T50 is the half remaining binding activity temperature measured using the membrane fraction gpBLT1 (0.4 μg protein) from preparative-scale expression. A representative result is shown in Fig. 2A. N.D.: not determined.

3.2. Screening of the stability of gpBLT1 mutants expressed in small-scale culture

The binding activities of five single gpBLT1 mutants, i.e., Ala56Asn2.40, His83Gly2.67, Lys88Gly3.21, Leu109Ser3.42, and Leu109Thr3.42, and 18 combinational gpBLT1 mutants, designed based on the multiple sequence alignment and known structures of GPCRs, were examined as described (Table 1). First, the membrane fractions were screened using all the 23 mutants, including the original dN15/Ser309Ala, expressed in small cultures of P. pastoris. The specific LTB4 binding activities were sustained in all the mutants except for the 12 mutants containing the Ala56Asn2.40 mutation with no binding capability, i.e., with loss of specific LTB4 binding (Table 1). The thermal stability of the active mutants was calculated as the relative remaining activity (%) of LTB4 binding after heat treatments at 40 °C to that of at 25 °C for each mutant.

Among the single mutations, His83Gly2.67 (68%) and Lys88Gly3.21 (75%) were much more thermally stable than the original dN15/Ser309Ala (45%), whereas both Leu1093.42 mutants, Leu109Ser3.42 (41%) and Leu109Thr3.42 (49%), did not exhibit increased thermal stability. The combinatorial mutant exhibited higher relative remaining activities than the single mutants, even for the Leu1093.42 mutants, which exhibited binding capabilities similar to that of the original protein. The triple mutants, His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21/Leu109Ser3.42 (95%) and His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21/Leu109Thr3.42 (93%), exhibited higher remaining specific activities than those of the double mutants. These results showed that mutations at His832.67, Lys883.21, and Leu1093.42 not only retained LTB4 ligand binding activity but also improved the thermal stability in an additive manner. The three double and triple combinational mutants His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21, His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21/Leu109Ser3.42, and His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21/Leu109Thr3.42 were selected for subsequent characterization studies after expression in preparative-scale culture.

3.3. Thermostability of the three combinatorial mutants expressed in preparative-scale culture

The thermostability of the mutants expressed by preparative-scale culture (1 L) was measured by determining the melting temperature (T50), defined as the heat treatment temperature at which 50% of LTB4 binding activity remained. In this experiment, we used three combinatorial gpBLT1 mutants and the original dN15/Ser309Ala (Fig. 2A); all of the selected mutants had T50 values of about 5 °C higher than that of the original protein. The T50 values for His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21, His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21/Leu109Ser3.42, His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21/Leu109Thr3.42, and the original dN15/Ser309Ala were 48.6±0.1, 47.9±0.0, 48.0±0.2, and 43.5±0.5 °C, respectively (Fig. 2A). However, the membrane fractions of triple mutants including Leu109Ser3.42 and Leu109Thr3.42 were further stabilized after small-scale expression (Table 1).

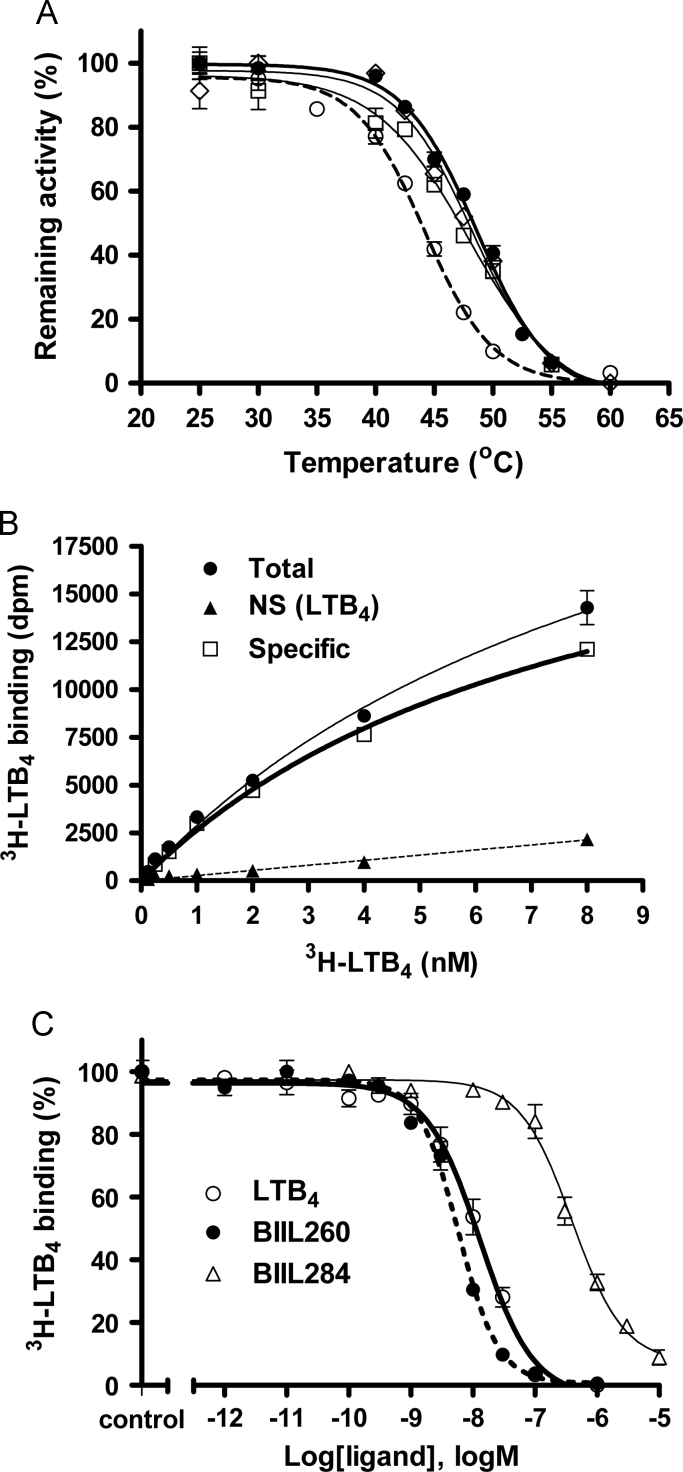

Fig. 2.

Thermal stabilities and ligand binding profiles of the membrane fractions of the BLT1 mutants after preparative-scale expression. (A) The thermal stabilities of LTB4 binding using BLT1 mutants in the membrane fraction. His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 (filled circles with thick line), His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21/Leu109Ser3.42 (open squares), His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21/Leu109Thr3.42 (open diamonds), and dN15/Ser309Ala as the original BLT1 (open circles with dotted line) are shown. The amount of LTB4 bound to the membrane fraction (0.4 μg protein) after heat treatment was normalized as the remaining activity, and the standard errors were calculated (n=3). (B) Saturation binding isotherm of LTB4 in the membrane fraction (0.4 μg protein), with standard errors (n=3). (C) Replacement assays for LTB4 with the antagonists BIIL260 and BIIL284, showing competitive binding to the membrane fraction (0.2 μg protein). Data include the standard errors (n=3).

The double mutation His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 had a ligand binding profile similar to that of the original protein for various ligands, as described previously [4]. The binding affinity for LTB4 (Kd=8.2 nM) was comparable to that of the original dN15/Ser309Ala (Kd=6.6 nM) in the saturation assay of membrane fractions (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the expression level (Bmax) of His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 was six times higher (311 pmol/mg) than that of the original (50 pmol/mg) [4]. The competitive ligand binding affinity (Ki=12.9 nM for LTB4, 5.8 nM for BIIL260, and 395 nM for BIIL284) was also comparable to that of the original dN15/Ser309Ala (Ki=3.8 nM for LTB4, 9.4 nM for BIIL260, and 165 nM for BIIL284; Fig. 2C). These results indicated that the double mutation of His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 improved the thermal stability of the protein without significantly affecting the ligand binding profile in gpBLT1.

3.4. Characterization of the purified His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 mutant

The most thermostable mutant (His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21) was expressed and purified by preparative scale culture, and ligand-binding capability and thermostability were measured. The purified His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 protein was produced at a yield of more than 1.0 mg from 1 L culture of P. pastoris. The purified mutant showed single monodispersion in gel-filtration analysis, as shown in the original purified protein [4]. The competitive ligand binding affinities of the purified mutant (IC50=2.4 nM for LTB4 and 6.4 nM for BIIL260; Fig. 3A) were similar to those of the mutant His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 in the membrane fraction (Fig. 2B and C). The solubilized and purified His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 showed less affinity for the moderate antagonist BIIL284 (Fig. 3A).

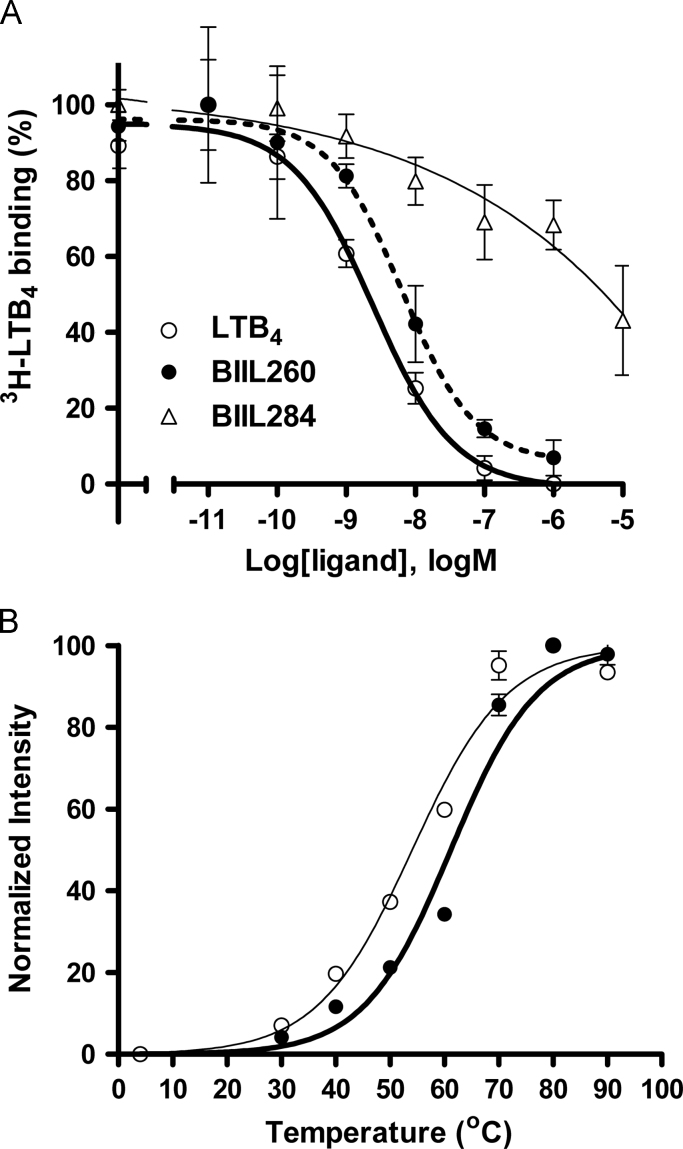

Fig. 3.

Ligand binding profiles and thermal stabilities of the purified BLT1 mutant, His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21. (A) Replacement assays of LTB4 with LTB4 (open circles) and the antagonists BIIL260 (filled circles) and BIIL284 (open triangles), showing competitive binding to the purified His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 (25 ng protein; n=3). (B) The thermal stabilities of the purified His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 (filled circles) and original BLT1 (open circles) using CPM assays (n=3).

The double mutant His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 exhibited significantly improved thermal stability after purification. The T50 values in the CPM assay were 61.5±0.1 and 57.3±0.1 °C for His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 and the original dN15/Ser309Ala, respectively (Fig. 3B). The discrepancy between the absolute T50 values obtained in the CPM assay versus the ligand binding assay (e.g., 61.5 and 48.6 °C, respectively, for the mutant His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21) could be explained by differences in the measurement methods. That is, the ligand-binding assay directly measures the amount of binding of the agonist LTB4 with gpBLT1, whereas the CPM assay titrates the solvent-exposed thiol group of cysteine in gpBLT1 with increasing temperature [27]. Additionally, the CPM assay subjects proteins to harsh conditions for denaturation. The thermal stabilization by the double His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21 mutant was improved by 4 °C in the purified state (Fig. 3B) and by about 5 °C in the membrane fraction (Fig. 2A).

4. Discussion

In this study, we performed structure-based rational mutations of gpBLT1 to enhance the thermal stabilization of the protein. Among the combinatorial mutants produced by rational designs, the double mutation of His83Gly2.67/Lys88Gly3.21, which was designed to stabilize the putative helix capping sites, improved the thermostability of gpBLT1 by 5 °C in the membrane fraction and by 4 °C in the DDM-solubilized and purified state. These results supported that the instability of the local site could influence the overall stability of the protein structure, as previously described in soluble proteins [31].

Lys88Gly3.21 was designed to stabilize the putative N-terminal end of TM-III of gpBLT1 by replacing the expected unfavorable residue Lys883.21 with a favorable Gly residue at the putative N-terminal capping site [32]. In all the N-terminal regions of TM-III for GPCRs of known structures, the capping site is at residue 3.21, and the N’’’→N4/N’’’W;N4C structural motif is conserved at this site [33] (Text S1). The amino acid sequence Trp3.18 (N”’)–Xxx3.19–(Phe/Leu)3.20–Gly3.21(Ncap)–(Xxx)33.22-24–Cys3.25(N4) is also conserved in most vertebrate BLT1s and other GPCRs but includes Lys883.21 in gpBLT1. We expected that gpBLT1 should have the same structural motif N’’’→N4/N’’’W;N4C and that Lys883.21 would be present as the capping residue. In this case, the positive charge of the amino group of the Lys residue side chain would become the repulsive force acting on the helix dipole of the TM-III, which would be unfavorable for protein stability.

The second His83Gly2.67 mutation at the C-terminal of TM-II is expected to be the other capping residue stabilizing the end of the helix. Unlike the N-terminus of TM-III, it was difficult to predict the specific C-terminal capping site of TM-II in gpBLT1. In the amino acid alignment, His832.67 was predicted to be the capping residue (Text S1). In 23 out of 28 vertebrate BLT1s, the corresponding residue 2.67 was the most favorable with Gly as the capping residue. The His832.67 side chain in gpBLT1 would not be expected to be favorable at the capping site because it would prevent solvation of the helix C-terminal end [32], [34] and would cause loss of entropy due to the conformational restrain of the side chain [35]. Moreover, the steric hindrance between its β-carbon and the backbone carbonyl should be unfavorable if His832.67 is in the left-handed helix (αL) conformation, as is often observed in the C-capping site [36]. In fact, the His83Gly2.67 mutation improved the remaining activity at 40 °C.

The stability of the capping site should be particularly important for TM helices fully embedded in the low dielectric constant membrane, and helix-capping mutations can be used to stabilize other GPCRs. In fact, a conserved interaction was observed between the main chain carbonyl groups of residues 7.54 and 7.55 at the C-terminal end of the TM-VII and the positive side chains of Arg or Lys in all of the GPCR crystal structures except those of the chemokine CXCR4 [18] and the neurotensin receptor [7]. A water molecule was found at the hollow of some helix-kinks of the TMs in the high-resolution crystal structure of GPCRs, indicating that the helix kink was stabilized by a “wedged” water with connecting hydrogen bonds burying the helix-kink gap to compensate for the loss of the hydrogen bond [37]. There are several solvent molecules at the helix end region in the A2AR high-resolution structure [14]. The stabilization of the helix end is expected to act as a stabilization element for the GPCR structure, providing electrostatic compensation for the α-helical dipole momentum edges, particularly in the molecular and membrane boundary regions where the effects are greater than in the bulk solvent region owing to the lower dielectric constant.

Mutations at the other two examined regions were not effective. In particular, mutation of Leu1093.42 at TM-III to Thr or Ser was expected to stabilize the cholesterol-binding site [25] by forming a hydrogen bond network with the Ser472.45 at TM-II and Trp1444.50 at TM-IV, as observed in the 15 known structures of GPCRs. Mutation of Leu1093.42 was useful for improving the thermal stability of BLT1 mutants in small-scale expression experiments but was not effective when using preparative-scale culture. The lipid composition of the cell membrane of P. pastoris may be different depending on culture size; however, the details of this phenomenon are still unclear. Alternatively, the Ala56Asn2.40 mutation causes complete loss of function of BLT1, but does not affect LTB4 binding directly because Ala562.40 is located between the TM helices close to the N-terminal region of TM-II at the cytoplasmic surface and is expected to be far from the ligand-binding site at the middle of the TM bundle [28]. The Ala56Asn2.40 mutation was expected to result in misfolding because this residue is essential for appropriate folding of the protein (text S1). These data indicate that creating a proper hydrogen bond in the folded TMs is critical because the hydrogen bond is geometrically stricter in terms of distance and direction than helix capping. Furthermore, the Gly residue present in the helix-capping region may be more adjustable due to the lack of a side chain. In this study on gpBLT1, double consecutive helix-capping mutations of the C-capping end of TM-II and the N-capping end of TM-III additively improved the thermal stabilization of the protein. These data supported the increased conformational adjustability in the helix-capping end by Gly residue substitution, with no restriction in position and orientation by hydrogen bond formation or steric hindrance by the side chain neighbor atoms.

In this study, the stabilization of the TM helix end was achieved for gpBLT1 by prediction of the helix-capping sites and replacement with Gly, and we propose the application of the helix-capping approach to stabilize other GPCRs having unfavorable residues at the helix-capping site. In the 17 crystal structures of GPCRs analyzed in this study, putative unfavorable capping sites were detected at 35 sites in 14 GPCRs. Among these helix-capping sites, we identified Coulomb repulsion occurring between similarly charged side chains against the α-helical dipole, the isolated helix end from the solvent by the bulkier side chain, and the left-handed helical (αL) conformation with non-Gly residues within the crystal structures. Similarly, out of the 274 human GPCRs, putative unfavorable residues were also found at 349 sites in the 209 GPCRs, where the repulsive charged amino acids and bulkier hydrophobic residues were located at the expected helix ends of the TM, as shown by simple searching of the multiple sequence alignments of the GPCR amino acid sequences. In contrast, it was not possible to predict the αL conformation of non-Gly residues. These results suggested that there may be unfavorable helix capping sites in many other GPCRs and that mutations at helix capping sites may be useful for stabilization of GPCR proteins, as shown in our rational approach with gpBLT1 in this study (Table S2).

In the ligand binding profiles of the mutants, we observed differences between membrane fractions containing expressed gpBLT1 and purified gpBLT1 samples, particularly for that of BIIL284, the prodrug of BIIL260. One possible explanation for this difference is the different lipidic environments of gpBLT1 in the P. pastoris membrane, causing variation in the lateral pressure and/or electrostatic potential patterns and in DDM-solubilized state. Indeed, these environments are completely different, both chemically and physically. BIIL284 is the ethoxycarbonyl prodrug of BIIL260 and has a larger molecular size than BIIL260 [38]. Therefore, it is possible that the binding affinity of the prodrug group of BIIL284 may be affected by the DDM-solubilized state of gpBLT1 to a greater extent than those of BIIL260 and LTB4.

5. Conclusion

In summary, our current structure-based rational approach for protein stabilization was less laborious than approaches described in previous stabilization studies using exhaustive Ala-scan mutations for crystallization of GPCRs with unknown structures [6], [7], [21]. Mutational design focusing on helix capping stabilization could be widely applicable for GPCR stabilization. However, the effects of independent mutation on improvement of protein stability should accumulate in an additive manner [39], and alternative approaches should be implemented to achieve sufficient stabilization for a variety of studies in addition to structural studies. Structural and functional predictions will become increasingly relevant, particularly predictions of the structure of the TM helix region in GPCRs, for both sample preparation of isolated active proteins and computer-aided drug design. In this study, we predicted which residues would be unfavorable for protein stability and replaced these residues with residues that would be physicochemically favorable, taking advantage of available structural and amino acid sequence information. Our results showed that this method was experimentally effective. However, it is difficult to predict the precise helix capping site in some TMs in GPCRs, thus it would be valuable that the criteria of the unfavorable or favorable residues at the helix capping site specific for the membrane proteins among limited helical transmembrane structures including GPCRs.

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that there is no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to T. Okuno (Juntendo University) for technical advice and useful discussions. This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MEXT) (#23770133, to T.H.) and grants from the MEXT-Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities (2013–2017).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.bbrep.2015.09.007.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Nakamura M., Shimizu T. Leukotriene receptors. Chem. Rev. 2011;11:6231–6298. doi: 10.1021/cr100392s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luster A.D., Tager A.M. T-cell trafficking in asthma: lipid mediators grease the way. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:711–724. doi: 10.1038/nri1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hicks A., Monkarsh S.P., Hoffman A.F., Goodnow R., Jr. Leukotriene B4 receptor antagonists as therapeutics for inflammatory disease: preclinical and clinical developments. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2007;16:1909–1920. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.12.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hori T., Sato Y., Takahashi N., Takio K., Yokomizo T., Nakamura M., Shimizu T., Miyano M. Expression, purification and characterization of leukotriene B4 receptor, BLT1 in Pichia pastoris. Protein Expr. Purif. 2010;72:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tate C.G., Schertler G.F. Engineering G protein-coupled receptors to facilitate their structure determination. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009;19:386–395. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warne T., Serrano-Vega M.J., Baker J.G., Moukhametzianov R., Edwards P.C., Henderson R., Leslie A.G., Tate C.G., Schertler G.F. Structure of a β1-adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2008;454:486–491. doi: 10.1038/nature07101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White J.F., Noinaj N., Shibata Y., Love J., Kloss B., Xu F., Gvozdenovic-Jeremic J., Shah P., Shiloach J., Tate C.G., Grisshammer R. Structure of the agonist-bound neurotensin receptor. Nature. 2012;490:508–513. doi: 10.1038/nature11558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherezov V., Rosenbaum D.M., Hanson M.A., Rasmussen S.G., Thian F.S., Kobilka T.S., Choi H.J., Kuhn P., Weis W.I., Kobilka B.K., Stevens R.C. High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human β2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2007;318:1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chien E.Y., Liu W., Zhao Q., Katritch V., Han G.W., Hanson M.A., Shi L., Newman A.H., Javitch J.A., Cherezov V., Stevens R.C. Structure of the human dopamine D3 receptor in complex with a D2/D3 selective antagonist. Science. 2010;330:1091–1095. doi: 10.1126/science.1197410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granier S., Manglik A., Kruse A.C., Kobilka T.S., Thian F.S., Weis W.I., Kobilka B.K. Structure of the delta-opioid receptor bound to naltrindole. Nature. 2012;485:400–404. doi: 10.1038/nature11111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haga K., Kruse A.C., Asada H., Yurugi-Kobayashi T., Shiroishi M., Zhang C., Weis W.I., Okada T., Kobilka B.K., Haga T., Kobayashi T. Structure of the human M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor bound to an antagonist. Nature. 2012;482:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature10753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanson M.A., Roth C.B., Jo E., Griffith M.T., Scott F.L., Reinhart G., Desale H., Clemons B., Cahalan S.M., Schuerer S.C., Sanna M.G., Han G.W., Kuhn P., Rosen H., Stevens R.C. Crystal structure of a lipid G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2012;335:851–855. doi: 10.1126/science.1215904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruse A.C., Hu J., Pan A.C., Arlow D.H., Rosenbaum D.M., Rosemond E., Green H.F., Liu T., Chae P.S., Dror R.O., Shaw D.E., Weis W.I., Wess J., Kobilka B.K. Structure and dynamics of the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Nature. 2012;482:552–556. doi: 10.1038/nature10867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu W., Chun E., Thompson A.A., Chubukov P., Xu F., Katritch V., Han G.W., Roth C.B., Heitman L.H., IJzerman A.P., Cherezov V., Stevens R.C. Structural basis for allosteric regulation of GPCRs by sodium ions. Science. 2012;337:232–236. doi: 10.1126/science.1219218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manglik A., Kruse A.C., Kobilka T.S., Thian F.S., Mathiesen J.M., Sunahara R.K., Pardo L., Weis W.I., Kobilka B.K., Granier S. Crystal structure of the μ-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature. 2012;485:321–326. doi: 10.1038/nature10954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimamura T., Shiroishi M., Weyand S., Tsujimoto H., Winter G., Katritch V., Abagyan R., Cherezov V., Liu W., Han G.W., Kobayashi T., Stevens R.C., Iwata S. Structure of the human histamine H1 receptor complex with doxepin. Nature. 2011;475:65–70. doi: 10.1038/nature10236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson A.A., Liu W., Chun E., Katritch V., Wu H., Vardy E., Huang X.P., Trapella C., Guerrini R., Calo G., Roth B.L., Cherezov V., Stevens R.C. Structure of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor in complex with a peptide mimetic. Nature. 2012;485:395–399. doi: 10.1038/nature11085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu B., Chien E.Y., Mol C.D., Fenalti G., Liu W., Katritch V., Abagyan R., Brooun A., Wells P., Bi F.C., Hamel D.J., Kuhn P., Handel T.M., Cherezov V., Stevens R.C. Structures of the CXCR4 chemokine GPCR with small-molecule and cyclic peptide antagonists. Science. 2010;330:1066–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.1194396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu H., Wacker D., Mileni M., Katritch V., Han G.W., Vardy E., Liu W., Thompson A.A., Huang X.P., Carroll F.I., Mascarella S.W., Westkaemper R.B., Mosier P.D., Roth B.L., Cherezov V., Stevens R.C. Structure of the human κ-opioid receptor in complex with JDTic. Nature. 2012;485:327–332. doi: 10.1038/nature10939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang C., Srinivasan Y., Arlow D.H., Fung J.J., Palmer D., Zheng Y., Green H.F., Pandey A., Dror R.O., Shaw D.E., Weis W.I., Coughlin S.R., Kobilka B.K. High-resolution crystal structure of human protease-activated receptor 1. Nature. 2012;492:387–392. doi: 10.1038/nature11701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lebon G., Warne T., Edwards P.C., Bennett K., Langmead C.J., Leslie A.G., Tate C.G. Agonist-bound adenosine A2A receptor structures reveal common features of GPCR activation. Nature. 2011;474:521–525. doi: 10.1038/nature10136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenbaum D.M., Zhang C., Lyons J.A., Holl R., Aragao D., Arlow D.H., Rasmussen S.G., Choi H.J., Devree B.T., Sunahara R.K., Chae P.S., Gellman S.H., Dror R.O., Shaw D.E., Weis W.I., Caffrey M., Gmeiner P., Kobilka B.K. Structure and function of an irreversible agonist-β2 adrenoceptor complex. Nature. 2011;469:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature09665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hino T., Arakawa T., Iwanari H., Yurugi-Kobayashi T., Ikeda-Suno C., Nakada-Nakura Y., Kusano-Arai O., Weyand S., Shimamura T., Nomura N., Cameron A.D., Kobayashi T., Hamakubo T., Iwata S., Murata T. G-protein-coupled receptor inactivation by an allosteric inverse-agonist antibody. Nature. 2011;482:237–240. doi: 10.1038/nature10750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Standfuss J., Xie G., Edwards P.C., Burghammer M., Oprian D.D., Schertler G.F. Crystal structure of a thermally stable rhodopsin mutant. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanson M.A., Cherezov V., Griffith M.T., Roth C.B., Jaakola V.P., Chien E.Y., Velasquez J., Kuhn P., Stevens R.C. A specific cholesterol binding site is established by the 2.8 Å structure of the human β2-adrenergic receptor. Structure. 2008;16:897–905. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ballesteros J.A., Weinstein H. Integrated methods for the construction of three dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors. Methods Neurosci. 1995;25:366–428. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexandrov A.I., Mileni M., Chien E.Y., Hanson M.A., Stevens R.C. Microscale fluorescent thermal stability assay for membrane proteins. Structure. 2008;16:351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bockaert J., Pin J.P. Molecular tinkering of G protein-coupled receptors: an evolutionary success. EMBO J. 1999;18:1723–1729. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palczewski K., Kumasaka T., Hori T., Behnke C.A., Motoshima H., Fox B.A., Trong I.L., Teller D.C., Okada T., Stenkamp R.E., Yamamoto M., Miyano M. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: a G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimamura T., Hiraki K., Takahashi N., Hori T., Ago H., Masuda K., Takio K., Ishiguro M., Miyano M. Crystal structure of squid rhodopsin with intracellularly extended cytoplasmic region. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:17753–17756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800040200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hori T., Moriyama H., Kawaguchi J., Hayashi-Iwasaki Y., Oshima T., Tanaka N. The initial step of the thermal unfolding of 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase detected by the temperature-jump Laue method. Protein Eng. 2000;13:527–533. doi: 10.1093/protein/13.8.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serrano L., Sancho J., Hirshberg M., Fersht A.R. α-Helix stability in proteins. I. Empirical correlations concerning substitution of side-chains at the N and C-caps and the replacement of alanine by glycine or serine at solvent-exposed surfaces. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;227:544–559. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90906-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aurora R., Rose G.D. Helix capping. Protein Sci. 1998;7:21–38. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson J.S., Richardson D.C. Amino acid preferences for specific locations at the ends of α helices. Science. 1988;240:1648–1652. doi: 10.1126/science.3381086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matthews B.W., Nicholson H., Becktel W.J. Enhanced protein thermostability from site-directed mutations that decrease the entropy of unfolding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1987;84:6663–6667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bang D., Gribenko A.V., Tereshko V., Kossiakoff A.A., Kent S.B., Makhatadze G.I. Dissecting the energetics of protein α-helix C-cap termination through chemical protein synthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:139–143. doi: 10.1038/nchembio766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyano M., Ago H., Saino H., Hori T., Ida K. Internally bridging water molecule in transmembrane α-helical kink. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2010;20:456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birke F.W., Meade C.J., Anderskewitz R., Speck G.A., Jennewein H.M. In vitro and in vivo pharmacological characterization of BIIL 284, a novel and potent leukotriene B4 receptor antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;297:458–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wells J.A. Additivity of mutational effects in proteins. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8509–8517. doi: 10.1021/bi00489a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material