Abstract

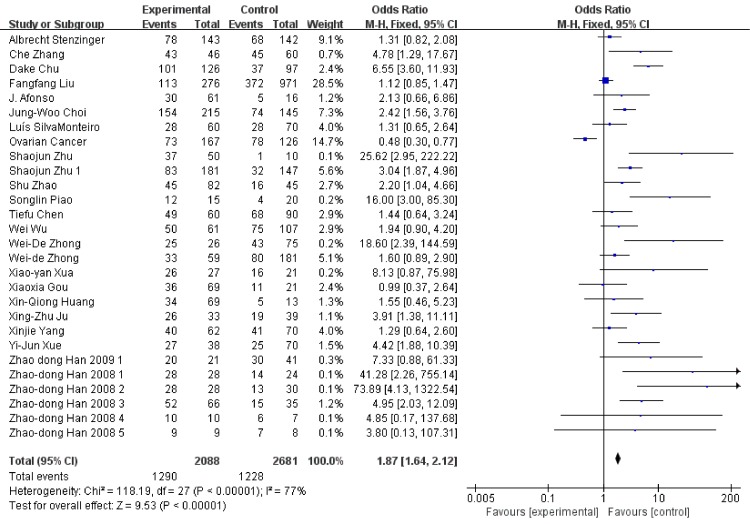

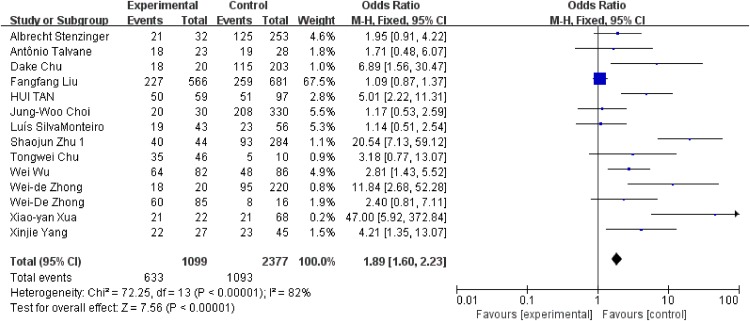

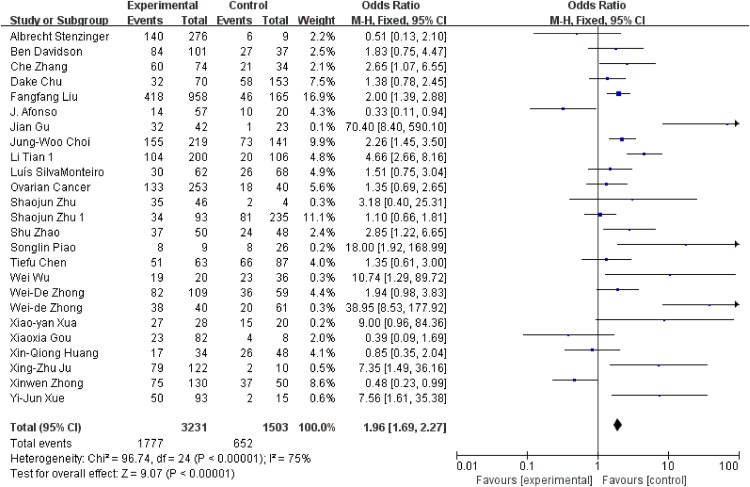

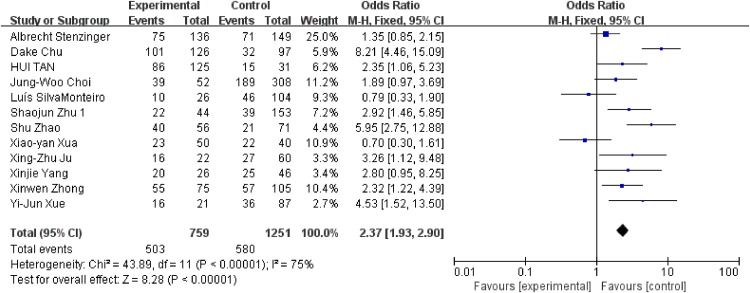

Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN) has been reported to be associated with tumor formation and invasion in many studies. However, the clinicopathological significance and prognosis of EMMPRIN in cancer patients remains inconclusive. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to assess the predictive potential of EMMPRIN in various cancers. By searching Pubmed, Cochrane library database and web of science comprehensively, 39studies with 5739 cases were included in our meta-analysis. The results indicated that EMMPRIN overexpression was significantly associated with poor outcome of cancers (HR=2.46, 95% CI: 2.21-2.75, P<0.0001). In addition, a significant relation was found between EMMPRIN overexpression and clinicopathological features, such as tumor stage (T3+T4/ T1+T2, OR=1.87, 95% CI:1.64-2.12, P<0.0001), tumor differentiation (poor/ well+ moderate, OR=1.09, 95% CI:1.60-2.23, P<0.0001), clinical stage (III+IV /I +II, OR=1.96, 95% CI:1.69-2.27, P<0.0001) and nodal metastasis (positive/negative, OR=2.37, 95% CI:1.93-2.90, P<0.0001). However, the expression of EMMRIN was not significantly associated with tumor stage in cervical cancer (OR=1.35, 95%CI: 0.73-2.48, P=0.33). In conclusion, EMMPRIN overxepression is significantly associated with clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of cancers. Thus, EMMPRIN may be regarded as a promising bio-marker in predicting the clinical outcome of patients in cancers and could be used as the therapeutic target during clinical practices.

Keywords: EMMPRIN, prognosis, clinicopathological significance, cancer, meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is a genetically and clinically diverse disease, with a tremendous amount of genetic heterogeneity across various malignant tumor types, invading and destroying nearby parts of the normal tissues [1]. The incidence and death rates of cancer are increasing in many cancer types, such as liver cancer, lung cancer and prostate cancer [2]. Besides, the survival rate of cancer patients tends to be poor for the lack of diagnostic methods with sensitivity and specificity in developing countries [3]. Latest research results predicted that biomarkers can be useful during the detection of cancers [4].

Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN, basigin, HAb18G, also known as CD147) is a type I transmembrane glycoprotein of the immunoglobulin superfamily with two immunoglobulin-like domains [5, 6]. EMMPRIN has been shown to be involved in various physiological as well as pathophysiological processes such as proliferation, migration, inflammation reaction and tumor invasion [7, 8]. An increasing number of studies have demonstrated that EMMPRIN is associated with tumor growth, invasion and angiogenesis in many malignant cancer, such as breast carcinoma [9], hepatocellular carcinoma [10] and prostate cancer [11], by regulating the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [12]. MMPs have been shown to decrease the angiogenesis of tumor cells and the expression of extracellular matrix, thereby contributing to tumor progression [13]. Recently, some research data indicated that expression of EMMPRIN was obviously higher in tumor tissues than adjacent normal tissues, indicating that EMMPRIN might be useful for the prediction of prognosis in cancers.

In this study, we performed a systematically meta-analysis to investigate the relationship between EPPRIN and cancers. The aim of this study is to evaluate the clinical significance of EPPRIN and its potential value when served as a prognostic indicator.

RESULTS

Search results and study characteristics

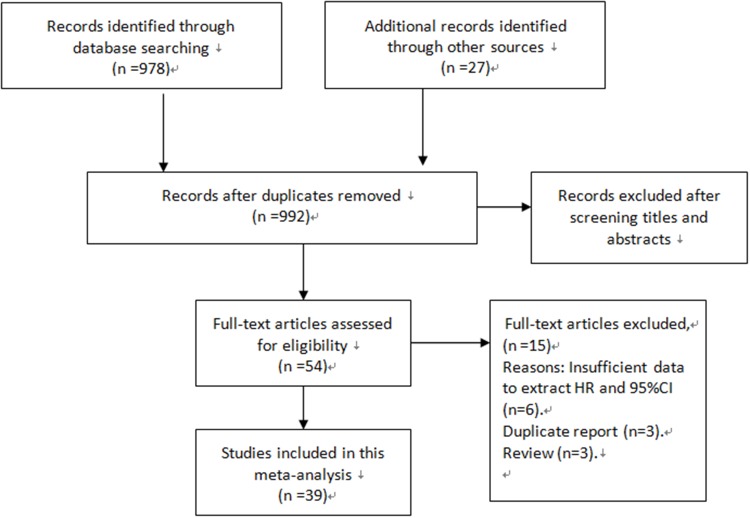

As presented in Figure 1, 992 potentially eligible studies from the databases were retrieved after duplicates removed. Through a carefully screening process, 938 articles were excluded. Of the remaining 54 studies, 15 studies were excluded for they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, 39 cohort studies were included in our meta-analysis [13–51].

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the study selection process.

The major characteristics of studies included were listed in Table 1. Among them, 29 were conducted in China, 3 from Germany, 2 from Portugal, 2 from Norway and 3 from America, Finland and Brazil respectively. We included a total of 5739 cases with different types of tumors, including bladder carcinoma, renal carcinoma, prostate carcinoma, penis carcinoma, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, thyroid carcinoma, ovarian carcinoma, glioblastoma. The testing methods of EMMPRIN were classified as immunohistochemistry (IHC) and tissue microassay. IHC staining was carried out using the paraffin-embedded block of cancer patients’ tissues compared to corresponding normal tissue, and the percentage of positive cells was calculated. The cut-off value was also list in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of 39 pooled studies evaluating the association between EMMPRIN overexpression and cancer.

| First author | Year | Country | Cancer type | Sample size | Mean age | Out comes | RR (95% CI) | Testing method | Cut-off value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhaodong Han1 | 2008 | China | Bladder carcinoma | 58 | 57.2± 11.2 | PFS | 3.66 (1.04-12.79) | IHC | 3+ (>51%) |

| Zhaodong Han2 | 2008 | China | Renal carcinoma | 52 | 56.8± 10.8 | PFS | 3.06 (0.82-11.44) | IHC | As above |

| Zhaodong Han3 | 2008 | China | Prostate carcinoma | 101 | 73.5± 12.3 | PFS | 4.87 (1.77-13.41) | IHC | As above |

| Zhaodong Han4 | 2008 | China | Penis carcinoma | 17 | 46.5± 9.2 | PFS | 2.38 (0.34-25.30) | IHC | As above |

| Zhaodong Han5 | 2008 | China | testis carcinoma | 17 | 48.6± 12.7 | PFS | 1.79 (0.22-19.94) | IHC | As above |

| Albrecht Stenzinger | 2011 | Germany | Colorectal cancer | 285 | 67 | OS | 3.09 (1.91-5.02) | Tissue microassay | NM |

| Jung-Woo Choi | 2014 | China | Bladder cancer | 360 | 69 | OS | 1.15 (0.50-2.67) | Tissue microassay | Scores 3 |

| WeiDe Zhong | 2010 | China | Bladder cancer | 101 | 68 | PFS/OS | 3.31 (1.07-15.72) | IHC | 1 (>10%) |

| HUI TAN | 2008 | China | Thyroid carcinoma | 156 | 46 | PFS | 3.31 (1.07-15.72) | IHC | 3+ (>51%) |

| Xiaoyan Xua | 2013 | China | Non-small cell lung cancer | 192 | 60 | OS | 6.63 (2.46-17.90) | IHC | 3+ (>51%) |

| J. Afonso | 2011 | Portugal | Bladder carcinoma | 77 | 71 | PFS/OS | 3.25 (1.02-10.39) | IHC | 1 (>5%) |

| Xinjie Yang | 2010 | China | Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 72 | 58 | OS | 2.78 (1.25-6.19) | IHC | NM |

| YauHua Yu | 2015 | America | squamous cell Carcinoma of the oral tongue | 31 | 60 | PFS/OS | 2.82 (0.60-13.26) | IHC | Grade 2 (>25%) |

| Pascale Fisel | 2015 | Germany | Clear cell renal cell Carcinoma | 186 | 64 | OS | 5.50 (2.50-12.10) | IHC | Score 3 |

| Daniel Buergy | 2009 | Germany | Colorectal cancer | 40 | 58 | OS | 2.50 (0.27-23.55) | IHC | >30% |

| Ovarian Cancer | 2007 | Finland | Ovarian cancer | 282 | 61 | PFS | 1.32 (0.98-1.80) | IHC | >10% |

| Ben Davidson | 2003 | Norway | Ovarian carcinoma | 41 | 59 | OS | 2.10 (0.76-5.81) | IHC | NM |

| Jian Gu | 2008 | China | Pediatric gliomas | 45 | 62 | PFS | 0.32 (0.11-2.09) | IHC | >51% |

| Songlin Piao | 2012 | China | Salivary duct carcinoma | 35 | 59 | PFS/OS | 2.95 (1.25-6.94) | IHC | Score 6 |

| Fangfang Liu | 2010 | China | Breast carcinoma | 110 | 53 | PFS/OS | 2.18 (0.61-7.81) | IHC | >30% |

| Antônio Talvane | 2012 | Brazil | Gastrointestinal stromal tumors | 64 | 62 | OS | 1.13 (0.24-5.25) | IHC | Score 3 |

| Min Yang | 2013 | China | Glioblastoma | 206 | 57 | OS | 2.42 (1.35-4.18) | IHC | Score 3 |

| Wei Wu | 2008 | China | Gallbladder carcinoma | 60 | 52 | OS | 0.49 (0.21-1.72) | IHC | >75% |

| Tiefu Chen | 2010 | China | Primary cutaneous Malignant melanoma | 150 | 53 | PFS/OS | 7.32 (1.19-20.29) | IHC | >10% |

| YiJun Xue | 2011 | China | Bladder cancer | 118 | 58 | OS | 2.33 (1.15-4.73) | IHC | >51% |

| Ying Liu | 2013 | China | Basal-like breast cancer | 126 | 56 | PFS/OS | 5.41 (0.74-39.49) | IHC | NM |

| Shaojun Zhu1 | 2013 | China | Colorectal cancer | 163 | 53 | OS | 8.88 (5.52-14.82) | IHC | Score 3 |

| Shaojun Zhu2 | 2013 | China | Colorectal cancer | 194 | 53 | OS | 3.51 (2.03-6.08) | IHC | As above |

| Shaojun Zhu3 | 2013 | China | Colorectal cancer | 213 | 53 | OS | 1.89 (1.06-3.38) | IHC | As above |

| Zhaodong Han1 | 2009 | China | Prostate Cancer | 39 | 74 | OS | 4.49 (0.29-69.18) | IHC | Score 2 (>25%) |

| Zhaodong Han2 | 2009 | China | Prostate Cancer | 34 | 74 | OS | 3.54 (0.24-51.94) | IHC | As above |

| Che Zhang | 2010 | China | Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma | 49 | 66 | OS | 0.98 (0.76-2.01) | IHC | >51% |

| Tongwei Chu | 2011 | China | Pediatric Medulloblastoma | 55 | 59 | OS | 3.50 (1.60-5.10) | IHC | Grade 2 (>10%) |

| Xiaoxia Gou | 2014 | China | Laryngeal | 48 | 64 | OS | 4.87 (0.47-23.50) | IHC | Score 3 |

| Xinwen Zhong | 2013 | China | Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma | 180 | 68 | OS | 2.01 (1.26-3.21) | IHC | Score 3 (>51%) |

| K Boye | 2012 | Norway | Colorectal cancer | 277 | NR | OS | 3.30 (1.40-7.80) | IHC | Score 2 (>25%) |

| Luís SilvaMonteiro | 2014 | Portugal | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas | 74 | 62 | OS | 3.89 (1.11-13.71) | IHC | Score 5 |

| XingZhu Ju | 2008 | China | Cervical Cancer | 82 | 52 | PFS | 1.23 (0.52-2.90) | IHC | >51% |

| XinQiong Huang | 2014 | China | Cervical Cancer | 132 | 51 | PFS | 5.12 (2.56-12.78) | IHC | >25% |

| LingMin Kong | 2011 | China | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 54 | 60 | OS | 2.13 (0.78-5.79) | Tissue microassay | Score 3 |

| Shu Zhao | 2013 | China | Ttriple-negative breast cancer | 127 | 47 | OS | 2.68 (1.08-6.66) | IHC | NM |

| Li Tian1 | 2013 | China | Astrocytic glioma | 182 | 65 | OS | 2.57 (1.41-4.83) | IHC | Score 3 |

| Li Tian2 | 2014 | China | Astrocytic glioma | 151 | 65 | OS | 4.52 (2.88-10.96) | IHC | As above |

| Li Tian3 | 2015 | China | Astrocytic glioma | 125 | 65 | OS | 6.61 (3.62-13.21) | IHC | As above |

| Dake Chu | 2013 | China | Gastric cancer | 223 | 60 | PFS/OS | 1.59 (1.05-2.40) | IHC | Score 3 |

| Weide Zhong | 2012 | China | Prostate cancer | 240 | 62 | OS | 3.08 (1.62-5.85) | Tissue microassay | NM |

| Shaojun Zhu | 2015 | China | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 50 | 65 | PFS | 2.41 (1.61-13.70) | IHC | >25% |

| Quan Zhou | 2011 | China | Osteosarcoma | 65 | 55 | PFS/OS | 5.33 (0.57-49.56) | IHC | >51% |

NR: not reporte; IRS: immunoreactivity score.

EMMPRIN overexpression and survival in cancers

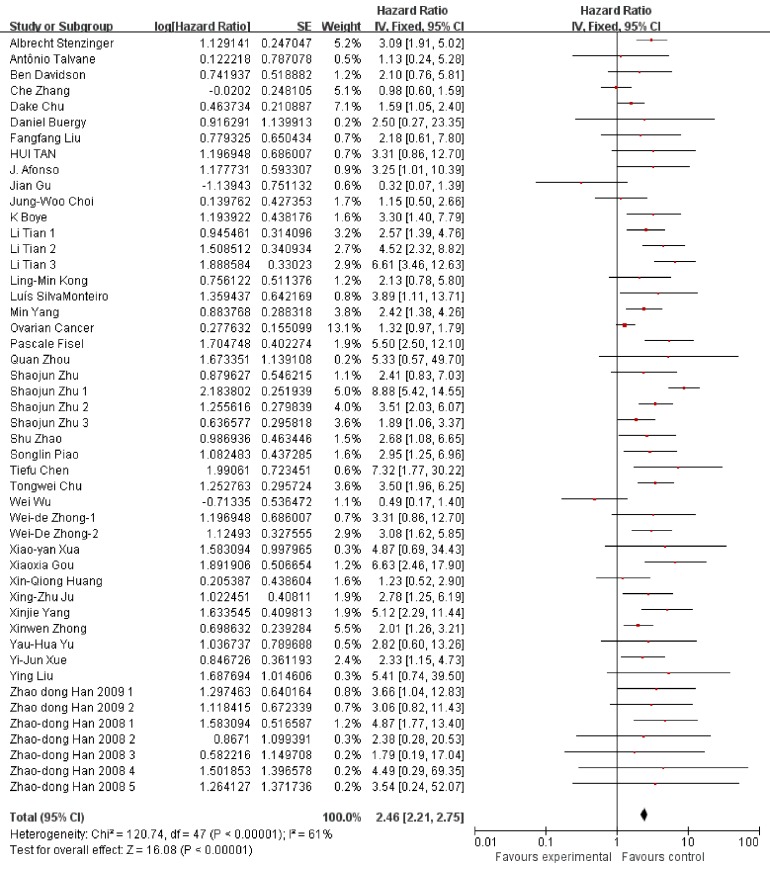

We used Hazard ratio (HR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) to estimate the prognostic value of EMMPPRIN overexpression in cancers. A fixed-effect model was used to conduct the analysis due to the Heterrogeneity test (I2=61%, P<0.00001). The results indicated that EMMPRIN was significantly associated with OS in cancers (HR=2.46, 95% CI: 2.21-2.75, P<0.0001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Association between EMMPRIN overexpression and the outcome of cancer patients.

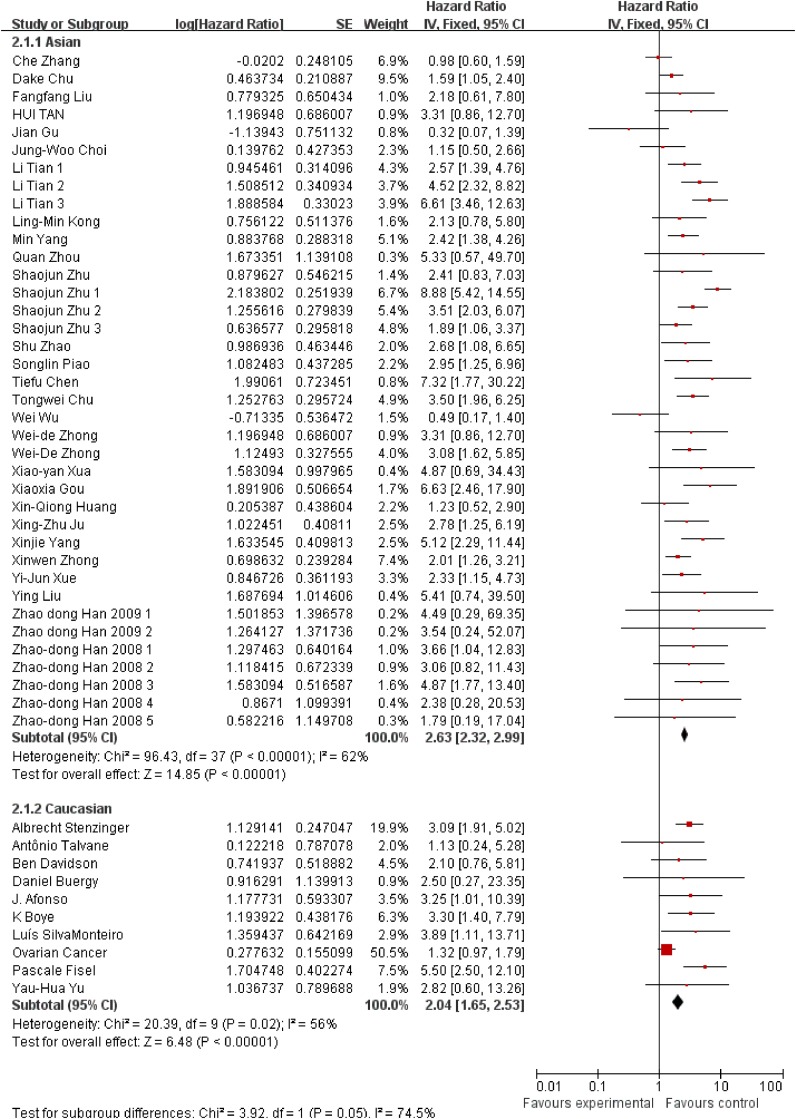

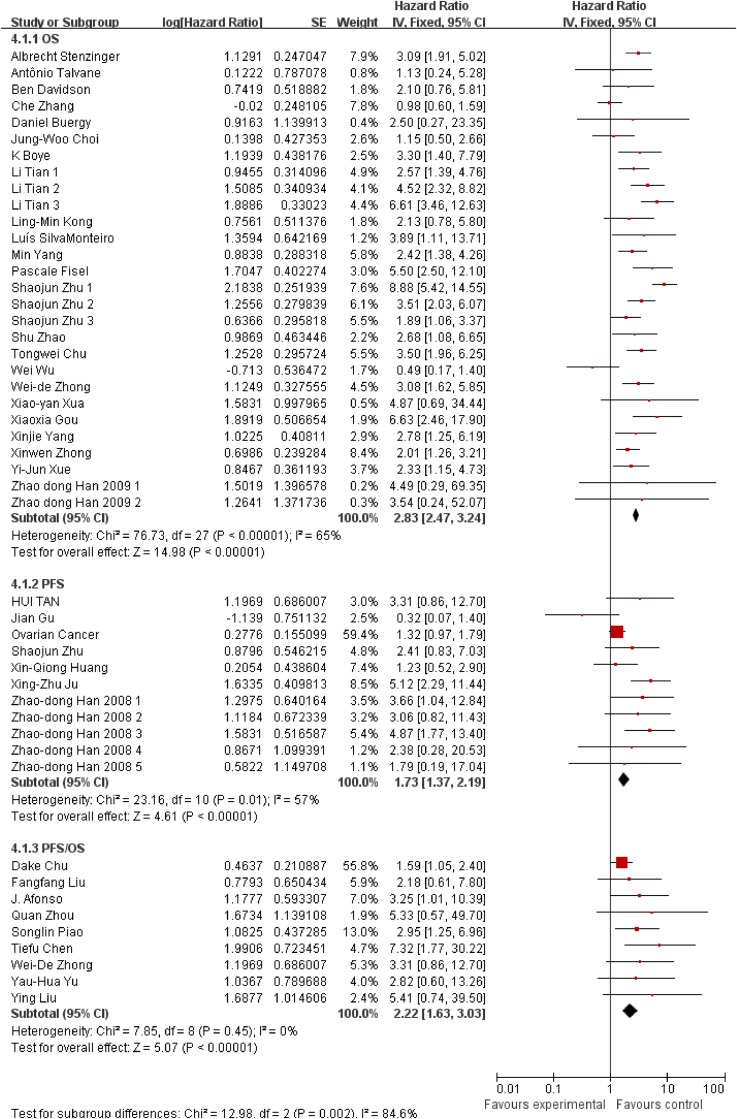

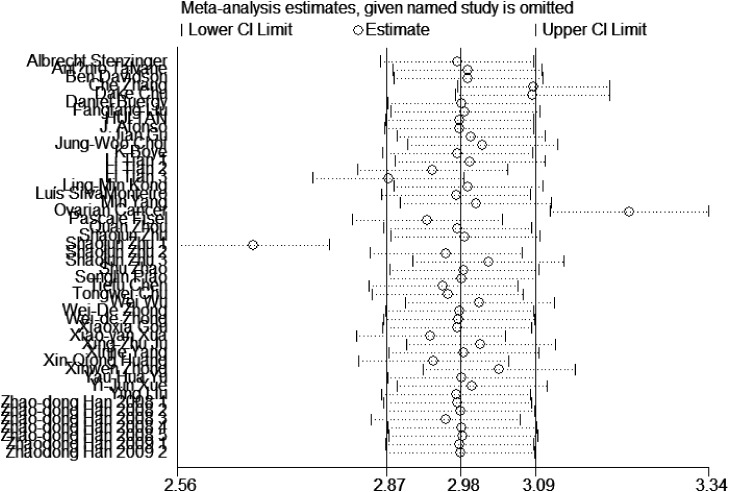

Besides, we also conducted subgroup analysis stratified by cancer type (Figure 3), ethnicity (Figure 4) and survival condition (Figure 5). Based on the cancer type group of studies, the investigation indicated that high EMMPRIN expression was associated with poor survival in bladder cancer (HR=2.21, 95% CI: 1.44-3.41, P<0.0001), prostate cancer (HR=3.54, 95% CI: 2.10-5.97, P<0.0001), gastrointestinal cancer (HR=2.96, 95% CI: 2.40-3.65, P<0.0001), breast cancer (HR=2, 75, 95% CI: 1.37-5.50, P<0.0001), cervical cancer (HR=2.63, 95% CI: 1.46-4.37, P<0.0001), hepatocellular cancer (HR=2.26, 95% CI: 1.09-4.69, P<0.0001), ovarian cancer (HR=1.37, 95% CI:1.02-1.83, P<0.0001), glioma (HR=2.77, 95%CI: 1.44-5.31, P=0.002) and others (HR=2.72, 95% CI: 1.88-3.95, P<0.0001). As for the population group of studies, both the Asian ethnicity (HR=2.63, 95% CI:2.32-2.99, P<0.0001) and Caucasian ethnicity (HR=2.04, 95% CI:1.65-2.63, P<0.0001), the EMMPRIN overexpression predicted a poor prognostic value in cancers. In addition, based on the survival condition, the subgroup results indicated that the high EMMPRIN was associated with OS (HR=2.83, 95% CI:2.47-3.24, P<0.0001), PFS (HR=1.73, 95% CI:1.37-2.19, P<0.0001) and OS/PFS (HR=2.22, 95% CI:1.63-3.03, P<0.0001). All the results summarized were presented in Table 2.

Figure 3. Subgroup analysis results based on tumor type.

Figure 4. Subgroup analysis results based on ethnicity.

Figure 5. Subgroup analysis results based on survival condition.

Table 2. Results of the overall and subgroup analyses for EMMPRIN overexpression and the outcome of cancer patients.

| Categories | No. of studies | Cases | Pooled HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 39 | 5739 | 2.46 | 2.21-2.75 | <0.0001 |

| Cancer types | |||||

| Bladder cancer | 5 | 714 | 2.21 | 1.44-3.41 | <0.0001 |

| Prostate cancer | 3 | 414 | 3.54 | 2.10-5.97 | <0.0001 |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 6 | 1459 | 2.96 | 2.40-3.65 | <0.0001 |

| Breast cancer | 3 | 363 | 2.75 | 1.37-5.50 | <0.0001 |

| Cervical cancer | 2 | 214 | 2.63 | 1.46-4.73 | <0.0001 |

| Hepatocellular cancer | 2 | 104 | 2.26 | 1.09-4.69 | <0.0001 |

| Ovarian cancer | 2 | 323 | 1.37 | 1.02-1.83 | <0.0001 |

| Others | 18 | 2148 | 2.60 | 2.18-3.10 | <0.0001 |

| Population | |||||

| Asian | 29 | 4382 | 2.63 | 2.32-2.99 | <0.0001 |

| Caucasian | 10 | 1357 | 2.04 | 1.65-2.63 | <0.0001 |

| Survival conditions | |||||

| OS | 23 | 3829 | 2.83 | 2.47-3.24 | <0.0001 |

| PFS | 7 | 992 | 1.73 | 1.37-2.19 | <0.0001 |

| OS/PFS | 9 | 918 | 2.22 | 1.63-3.03 | <0.0001 |

Moreover, because the clinicopathological characteristics and driven factors are different in different cancers, we conducted a subgroup analysis during the tumor-stage-analysis based on cancer types (Supplementary Figure 1). The results indicated that high expression of EMMPRIN predicted an advanced tumor stage, which means our conclusion was relatively consistent, except for cervical cancer (HR=1.35, 95%CI: 0.73-2.48, p=0.33). According to our analysis, the expression of EMMRIN was not significantly associated with tumor stage in cervical cancer.

Besides, the cut-off value was not consistent among the studies included, thus we conducted a subgroup analysis based on the criteria of positive expression definition. The high cut-off value was identified when the percentage of positive cells is more than 50% or the scores are more than 3. And the low cut-off value was indentified when the percentage of positive cells is less than 50% and the scores are less than 3. Besides, 5 studies [35, 45, 46, 52, 53] enrolled in our meta-analysis provided no information of the cu-off value. Thus, these 5 studies were not included in the present subgroup analysis based on the criteria of positive expression definition. The results indicated that the high or low cut-off value didn’t affect our conclusion obviously (High: HR=2.76, 95%CI: 2.62-2.90, Low: HR=2.38, 95%CI: 2.33-2.44). Both the high cut-off value group and the low cut-off value group suggested the corresponding overexrepssion of EMMRIN predicted a poor prognosis outcome in cancers (Supplementary Figure 2).

EMMPRIN overexpression and clinicopathological features

All the results assessing the association between clinicopathological features and EMMPRIN expression were presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Results of clinicopathological factors related to EMMPRIN overexpression.

| Subgroup | No. of studies | Cases | Pooled OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor stage (T3+T4/T1+T2) | 24 | 4769 | 1.87 | 1.64-2.12 | <0.0001 |

| Differentiation (poor/ well +moderate) | 14 | 3476 | 1.09 | 1.60-2.23 | <0.0001 |

| Clinical stage (III+IV/I+II) | 25 | 4734 | 1.96 | 1.69-2.27 | <0.0001 |

| Nodal metastasis (negative/ positive) | 12 | 2010 | 2.37 | 1.93-2.90 | <0.0001 |

We conducted analysis evaluating the clinicopathological features and EMMPRIN expression from the following aspects: tumor stage (Figure 6), differentiation (Figure 7), clinical stage (Figure 8) and nodal metastasis (Figure 9).

Figure 6. Association between EMMPRIN overexpression and tumor stage.

Figure 7. Association between EMMPRIN overexpression and tumor differentiation.

Figure 8. Association between EMMPRIN overexpression and clinical stage.

Figure 9. Association between EMMPRIN overexpression and nodal metastasis.

Among the included studies, 24 studies reported risk between high EMMPRIN expression and tumor stage. The results obviously indicated that the positive rate of EMMPRIN expression was significantly higher in cancers with tumor stage T3+T4 than with stageT1+T2 (OR=1.87, 95% CI:1.64-2.12, P<0.0001). Besides, the EMMPRIN overexpression was significantly associated with tumor differentiation (poor/ well+ moderate) (OR=1.09, 95% CI:1.60-2.23, P<0.0001). Stratified based on the clinical stage, the results showed a significant association between EMMPRIN expression and the risk of clinical stage III+IV than stage I +II (OR=1.96, 95% CI:1.69-2.27, P<0.0001). 12 studies compared the EMMPRIN expression negative nodal metastasis and positive nodal metastasis. The results showed that a higher EMMPRIN expression indicated a positive nodal metastasis (OR=2.37, 95% CI:1.93-2.90, P<0.0001).

Quality assessment and sensitivity analysis

The quality of each study included in our meta-analysis was assessed using The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). A star system was used to calculate the score of each study and a study award with 5 scores or more was considered as high quality article. The scores of the 39 studies include in our research ranged from 7 to 9.

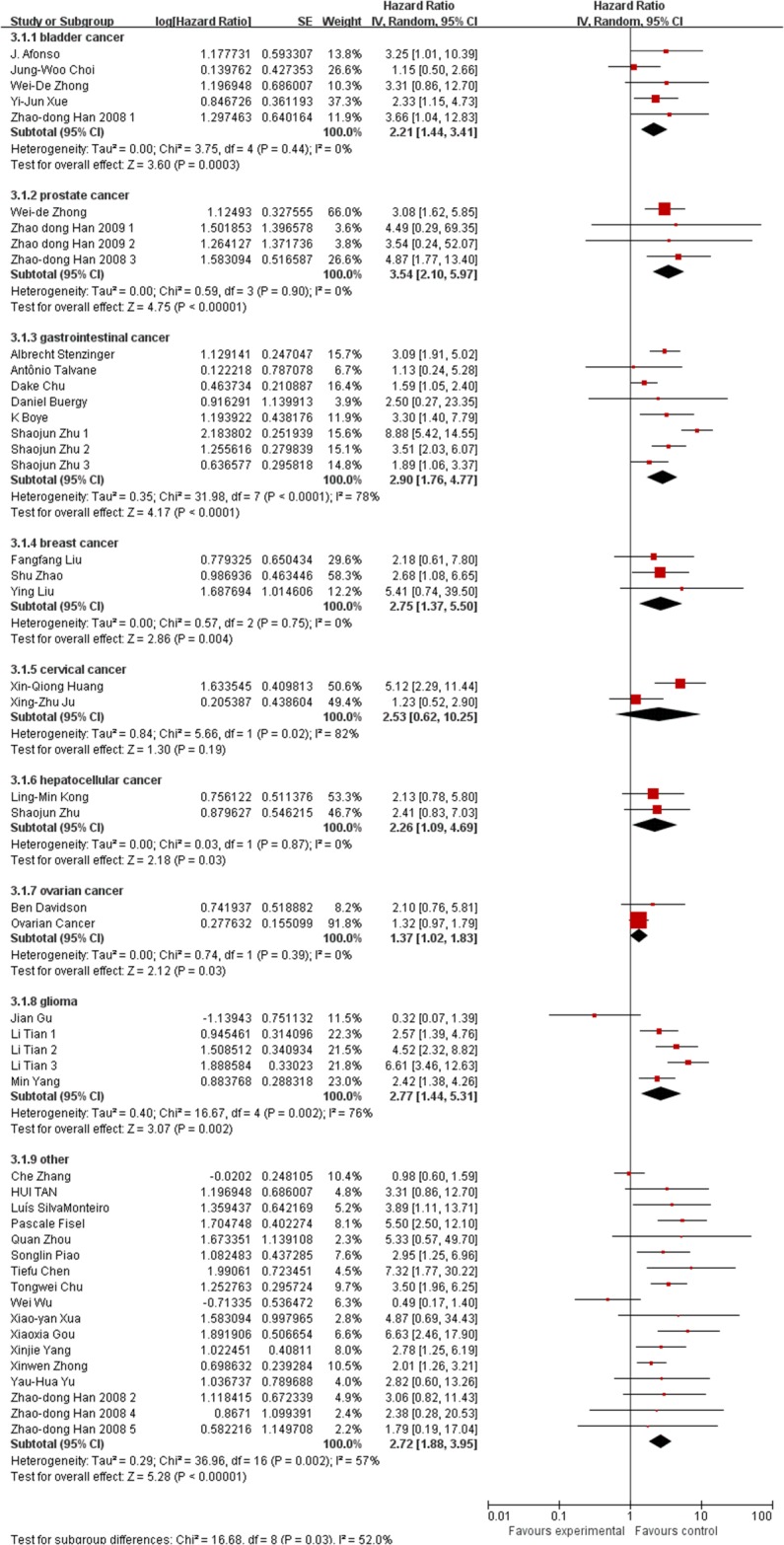

By omitting one individual study a time, sensitivity analysis between EMMPRIN overexpression and survival of cancer was conducted to investigate the potential sources of heterogeneity (Figure 10). The results indicated that overall risk estimate did not change, indicating a stable result of our meta-analysis.

Figure 10. Sensitivity test among studies included.

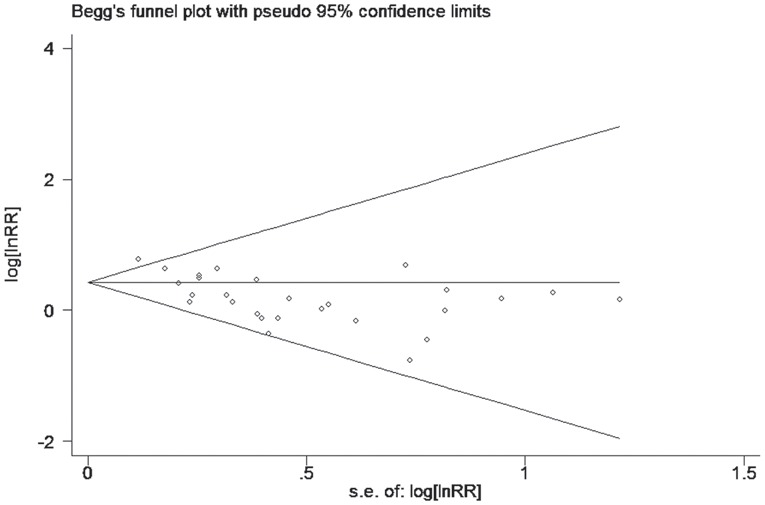

Publication bias

According to the funnel plot (Figure 11), no evidence of obvious asymmetry existed. Furthermore, Begg’s funnel plot and Egger;s regression were also conducted to estimate the publication bias. The results (Table 4) showed no significant publication bias for pooled HR estimation. Similarly, there is no publication bias existed in the OR estimation and the subgroup of the analysis.

Figure 11. Funnel plot analysis investigating the publication bias between EMMPRIN overexpreession and cancer prognosis.

Table 4. Results of Egger’s and Begg’s tests.

| Comparison | N | Egger's test | Begg's test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | P-value | 95% CI | Z | P-value | ||

| Overall | 48 | 1.4 | 0.167 | (-0.30-1.69) | 0.02 | 0.986 |

| OS | 28 | -0.15 | 0.879 | (-1.89-1.63) | 0.18 | 0.859 |

| PFS | 11 | 1.31 | 0.224 | (-0.73-2.71) | 0.62 | 0.533 |

| OS/PFS | 9 | 4.67 | 0.002 | (0.77-2.34) | 1.15 | 0.251 |

| Caucasian | 10 | 1.71 | 0.127 | (-0.47-3.12) | 0.89 | 0.371 |

| Asian | 38 | 0.45 | 0.653 | (-0.97-1.53) | 0.62 | 0.538 |

DISCUSSION

Most cancer deaths are due to metastasis with proliferation and angiogenesis [54]. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), found in extracellular milieu of various tissues, are reported to be associated with poor survival of cancer patients [55]. Because of the specific structure, MMPs are responsible for the cancer metastasis, invasion, angiogenesis and tumorigenesis [56, 57]. And the MMPs are obviously up-regulated by the stimulated EMMPRIN, which makes EMMPRIN get involved with tumor metastasis [58]. It’s reported that EMMPRIN and MMP-9 can be found in normal keratinocytes [59] and tumor cells [60] and the expression of EMMPRIN is much higher in tumor tissues than the adjunct normal tissues [61]. Besides, EMMPRIN can interact with a verity of proteins, such as VEGF [62], lewis y antigen [63], caveolin-1 [64], cyclooxygenase-2 [65] and fascin [66], executing its effect on tumorigenesis by regulating tumor cell invasion, metastasis and adhesion.. Emerging evidence indicate that EMMPRIN is associated with prognosis of various cancers, however, the exact effects remains vaguely.

In the present study, the data from 39 studies with 5739 cases were analyzed to assess the association between EMMPRIN overexpression and its prognostic value in cancer. According to our analysis, EMMPRIN was significantly associated with poor outcome of cancer patients (HR=2.46, 95% CI: 2.21-2.75, P<0.0001). It’s been reported that in hepatocellular carcinomas, higher EMMPRIN expression correlates significantly with poor survival of patients. In breast cancer, the OS of patients with higher EMMPRIN expression was much shorter than those with lower EMMPRIN expression. The same situation also exists in other cancers. Our finding is consistent with the previous studies investigating the roles of EMMPRIN overexpression. Besides, our results revealed that higher expression of EMMPRIN was also an independent risk factor for the survival of cancer patients in Asian and Caucasian based on the subgroup stratified by ethnicity. The similar results are summarized when stratified by survival conditions.

To further investigate the prognostic value of EMMPRIN, the relationship between EMMPRIN expression and the clinicopathological factors was also analyzed in our meta-analysis. Our results suggested that higher EMMPRIN expression was obviously associated with worse clinicopathological features, including tumor stage (T3+T4/T1+T2), except for cervical cancer (HR=1.35, 95%CI:0.73-2.48, p=0.33), poor/ well+ moderate differentiation rate, clinical stage (III+IV / I +II) and nodal metastasis (negative/positive). This may also verify the strong association between EMMPRIN expression and the survival of tumor patients. This might be the first study to evaluate the clinicopathological significance of EMMPRIN in cancers. However the other clinicopathological factors, such as age, tumor location and sex, were not included in our analysis. Considering the complicacy of clinicopathological features, more studies on large populations are encouraged.

Because of the inconsistent method to test the EMMPRIN expression and positive criteria, we also analyzed the corresponding heterogeneity. Among all the 39 studies, 4 studies used TMA to detect the expression of EMMPRIN; the rest 35 studies used IHC to detect the expression of EMMPRIN, as indicated in our revised Table 1. Among these, 5 studies didn’t mention the cut-off value of positive expression of EMMPRIN. Both the percentage of positive cells and the intensity of staining scores were used according to different studies. However, the results indicated that our conclusion was relatively consistent. No obvious discrepancy was found during the analysis. Although the pathogeneses of different cancer types are divergent, our results could prove the prognostic value of EMMPRIN in cancers for the reasons below. First, high expression of EMMPRIN predicted worse overall survival in each sub grouped cancer. Second, elevated EMMPRIN expression was significantly associated with poor survival of cancer patients in a pooled analysis in all included cancers. It means that EMPPRIN might be a universally applicable biomarker in cancers.

The mechanism lied behind this correlation still remain unknown. MMPs stimulated by EMMPRIN in human cancers may account for one of these mechanisms. By activating signal transduction cascades through degrading extracellular matrix proteins, MMPs can enhance tumor metastasis and invasion [37]. It’s also been demonstrated that tumor progression could be inhibited by silencing EMMPRIN by RNA interference approach [67, 68]. In order to select a therapeutic strategy and to allocate medical resources with reasonableness, an accurate method to predict the prognosis of cancer patients is required [69]. Our meta-analysis concluded that EMMPRIN could be a prognostic marker in solid tumors.

However, some limitations still exist in result of the current meta-analysis. First, for subgroup analysis stratified by cancer type, some types have insufficient studies to summarize the main effect, such as gallbladder carcinoma and penis carcinoma. Second, several studies included used Engage Digitizer 4.1 to estimate the data because only Kaplan-Meier curve was provided, thereby leading to unavoidable calculation errors. Third, some clinicopathological factors, such as age, tumor location and sex, were not included in our analysis due to the insufficient data. Fourth, the cut-off values were inconsistent in the studies included, and this could be one source of heterogeneity. Therefore, more well-designed studies are needed to validate the findings of the current study.

In conclusion, EMMPRIN overexpression predicts a poor prognosis outcome of cancer patients and is significantly relevant to clinicopathological features. Therefore, EMMPRIN might be a reasonable prognostic bio-maker and therapeutic target of cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

There is no review protocol exists.

Literature search

We comprehensively searched for published literature by consulting the electronic database PubMed, Cochrane Library databases and Web of Science before October 10, 2016, without language and publication restrictions. Studies were selected using the following terms: “Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer” or “EMMPRIN” or “CD147” or “HAb18G” and “basigin” in combination with “cancer,” “tumor,” “carcinoma” and “neoplasm”. The references of retrieved articles were also reviewed for any potential eligible data and authors were contacted for specific information if necessary. Oncomine (User ID: 1610636@tongji.edu.cn) and TCGA (analyzed by cBioPortal) were searched to make our research complete. The literature search was performed independently by H. Fan and W. Yi with double check and consensus to resolve all the disagreements.

Study selection

The studies were included if they met the following criteria: 1) the article enrolled should be case-control and cohort study; 2) expression of EPPRIN needs to be identified as positive with specific methods in cancer patients; 3) the relationship between EPPRIN expression and the time-to-event outcome, which was precisely defined, was reported; 4) sufficient data was provided to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and the hazard ratio (HR) with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) (ether directly obtained or indirectly calculated from Kaplan-Meier survival curves). Studies were ineligible if they were case reports, reviews, letters, duplicate studies, and articles without sufficient data. If more than one article focused on the same population, we preferred the latest one.

Data extraction

Information was carefully extracted from all the eligible studies by two investigators (H. Fan and C. Wang) independently, including: the first author’s name, publication year, the ethnicity, cancer type, sample size, testing method, survival condition, duration of follow-up, EPPRIN expression data and the HRs and ORs with the corresponding 95% CI. Software Engauge Digitizer 4.1 was used to extract data if the study provided a Kaplan-Meier curve only.

Quality assessment

We used Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) to evaluate the quality of every study enrolled. Each item could be awarded with one point when meeting the requirement (total score ranged from 0 to 9). Studies got a score of 6 or more were considered to be of high quality.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager 5.3 was used to perform all statistical analyses. Hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to evaluate the significance of the association between EPPRIN expression and the outcome of patients. The odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95%CI were used to analyze the correlation between EPPRIN overexpression and clinicopathological parameters, such as tumor stage, nodal metastasis and clinical grade. Q-test and I2 index were used to assess the heterogeneity between studies. A random-effects model was conducted when the heterogeneity was considered statistically significant (P<0.01). Otherwise, a fixed-effects model was conducted. Begg’s and Egger’s asymmetry tests were used to assess the potential publication bias. By omitting a study one time, sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the stability of our results. Begg’s and Egger’s asymmetry tests and sensitivity analysis were performed by STATA software version 12.0 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS FIGURES

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this thesis. And thanks for the great ideal of J. Wang. We also gratefully acknowledge the help of professors for polishing our language.

Abbreviations

- EMMPRIN

extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer

- HR

hazard ratio

- OR

odds ratio

- MMPs

matrix metalloproteinases

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- CI

confidence interval

- OS

overall survival

- PFS

progression-free survival

Author contributions

The literature search was performed independently by H. Fan and W. Yi with double check and consensus to resolve all the disagreements. Information was carefully extracted from all the eligible studies by H. Fan and C. Wang independently. The statistical analysis was conducted by H. Fan, W. Yi, C. Wang and J. Wang. And the ideas of this meta-analysis was designed by J. Wang.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

FUNDING

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Das J, Gayvert KM, Yu H. Predicting cancer prognosis using functional genomics data sets. Cancer Inform. 2014;13:85–8. doi: 10.4137/CIN.S14064. https://doi.org/10.4137/CIN.S14064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu G, Zhang X, Wang Y, Xiong H, Zhao Y, Wang J, Sun F. Prognostic value of melanoma cell adhesion molecule expression in cancers: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:12056–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rich N, Singal AG. Hepatocellular carcinoma tumour markers: current role and expectations. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:843–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.07.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu XL, Hu T, Du JM, Ding JP, Yang XM, Zhang J, Yang B, Shen X, Zhang Z, Zhong WD, Wen N, Jiang H, Zhu P, et al. Crystal structure of HAb18G/CD147: implications for immunoglobulin superfamily homophilic adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18056–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802694200. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M802694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang Y, Kesavan P, Nakada MT, Yan L. Tumor-stroma interaction: positive feedback regulation of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN) expression and matrix metalloproteinase-dependent generation of soluble EMMPRIN. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabison EE, Huet E, Baudouin C, Menashi S. Direct epithelial-stromal interaction in corneal wound healing: Role of EMMPRIN/CD147 in MMPs induction and beyond. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:19–33. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2008.11.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang Y, Nakada MT, Kesavan P, McCabe F, Millar H, Rafferty P, Bugelski P, Yan L. Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer stimulates tumor angiogenesis by elevating vascular endothelial cell growth factor and matrix metalloproteinases. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3193–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3605. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou S, Liu C, Wu SM, Wu RL. [Expressions of CD147 and matrix metalloproteinase-2 in breast cancer and their correlations to prognosis]. [Article in Chinese] Ai Zheng. 2005;24:874–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Shang P, Qian AR, Wang L, Yang Y, Chen ZN. Inhibitory effects of antisense RNA of HAb18G/CD147 on invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2174–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i10.2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhong WD, Han ZD, He HC, Bi XC, Dai QS, Zhu G, Ye YK, Liang YX, Qin WJ, Zhang Z, Zeng GH, Chen ZN. CD147, MMP-1, MMP-2 and MMP-9 protein expression as significant prognostic factors in human prostate cancer. Oncology. 2008;75:230–6. doi: 10.1159/000163852. https://doi.org/10.1159/000163852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rucci N, Millimaggi D, Mari M, Del Fattore A, Bologna M, Teti A, Angelucci A, Dolo V. Receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand enhances breast cancer-induced osteolytic lesions through upregulation of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer/CD147. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6150–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2758. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han ZD, He HC, Bi XC, Qin WJ, Dai QS, Zou J, Ye YK, Liang YX, Zeng GH, Zhu G, Chen ZN, Zhong WD. Expression and clinical significance of CD147 in genitourinary carcinomas. J Surg Res. 2010;160:260–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.11.838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2008.11.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisel P, Stuhler V, Bedke J, Winter S, Rausch S, Hennenlotter J, Nies AT, Stenzl A, Scharpf M, Fend F, Kruck S, Schwab M, Schaeffeler E. MCT4 surpasses the prognostic relevance of the ancillary protein CD147 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:30615–27. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5593. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.5593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson B, Goldberg I, Berner A, Kristensen GB, Reich R. EMMPRIN (extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer) is a novel marker of poor outcome in serous ovarian carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:161–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1022696012668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu FF, Cui LF, Zhang Y, Chen L, Wang YH, Fan Y, Lei T, Gu F, Lang R, Pringle GA, Zhang X, Chen Z, Fu L. Expression of HAb18G is associated with tumor progression and prognosis of breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124:677–88. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0790-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han ZD, Bi XC, Qin WJ, He HC, Dai QS, Zou J, Ye YK, Liang YX, Zeng GH, Chen ZN, Zhong WD. CD147 expression indicates unfavourable prognosis in prostate cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:369–74. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9131-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gou X, Chen H, Jin F, Wu W, Li Y, Long J, Gong X, Luo M, Bi T, Li Z, He Q. Expressions of CD147, MMP-2 and MMP-9 in laryngeal carcinoma and its correlation with poor prognosis. Pathol Oncol Res. 2014;20:475–81. doi: 10.1007/s12253-013-9720-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ju XZ, Yang JM, Zhou XY, Li ZT, Wu XH. EMMPRIN expression as a prognostic factor in radiotherapy of cervical cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:494–501. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang XQ, Chen X, Xie XX, Zhou Q, Li K, Li S, Shen LF, Su J. Co-expression of CD147 and GLUT-1 indicates radiation resistance and poor prognosis in cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:1651–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afonso J, Longatto-Filho A, Baltazar F, Sousa N, Costa FE, Morais A, Amaro T, Lopes C, Santos LL. CD147 overexpression allows an accurate discrimination of bladder cancer patients' prognosis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37:811–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.06.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boye K, Nesland JM, Sandstad B, Haugland Haugen M, Mælandsmo GM, Flatmark K. EMMPRIN is associated with S100A4 and predicts patient outcome in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:667–74. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.293. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buergy D, Fuchs T, Kambakamba P, Mudduluru G, Maurer G, Post S, Tang Y, Nakada MT, Yan L, Allgayer H. Prognostic impact of extracellular matrix metalloprotease inducer. Cancer. 2009;115:4667–78. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24516. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen T, Zhu J. Evaluation of EMMPRIN and MMP-2 in the prognosis of primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Med Oncol. 2010;27:1185–91. doi: 10.1007/s12032-009-9357-y. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-009-9357-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi JW, Kim Y, Lee JH, Kim YS. Prognostic significance of lactate/proton symporters MCT1, MCT4, and their chaperone CD147 expressions in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Urology. 2014;84:245.e9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.03.031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu D, Zhu S, Li J, Ji G, Wang W, Wu G, Zheng J. CD147 expression in human gastric cancer is associated with tumor recurrence and prognosis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101027. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu T, Chen X, Yu J, Xiao J, Fu Z. Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer is a negative prognostic factor of pediatric medulloblastoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2011;17:705–11. doi: 10.1007/s12253-011-9373-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12253-011-9373-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Oliveira AT, Pinheiro C, Longatto-Filho A, Brito MJ, Martinho O, Matos D, Carvalho AL, Vazquez VL, Silva TB, Scapulatempo C, Saad SS, Reis RM, Baltazar F. Co-expression of monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) and its chaperone (CD147) is associated with low survival in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2012;44:171–8. doi: 10.1007/s10863-012-9408-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10863-012-9408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu J, Zhang C, Chen R, Pan J, Wang Y, Ming M, Gui W, Wang D. Clinical implications and prognostic value of EMMPRIN/CD147 and MMP2 expression in pediatric gliomas. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:705–10. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0828-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-008-0828-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kong LM, Liao CG, Chen L, Yang HS, Zhang SH, Zhang Z, Bian HJ, Xing JL, Chen ZN. Promoter hypomethylation up-regulates CD147 expression through increasing Sp1 binding and associates with poor prognosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1415–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01124.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01124.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, Xin T, Jiang QY, Huang DY, Shen WX, Li L, Lv YJ, Jin YH, Song XW, Teng C. CD147, MMP9 expression and clinical significance of basal-like breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2013;30:366. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0366-x. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-012-0366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monteiro LS, Delgado ML, Ricardo S, Garcez F, do Amaral B, Pacheco JJ, Lopes C, Bousbaa H. EMMPRIN expression in oral squamous cell carcinomas: correlation with tumor proliferation and patient survival. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:905680. doi: 10.1155/2014/905680. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/905680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piao S, Zhao S, Guo F, Xue J, Yao G, Wei Z, Huang Q, Sun Y, Zhang B. Increased expression of CD147 and MMP-9 is correlated with poor prognosis of salivary duct carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:627–35. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-1142-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-011-1142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sillanpaa S, Anttila M, Suhonen K, Hamalainen K, Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T, Puistola U, Tammi M, Sironen R, Saarikoski S, Kosma VM. Prognostic significance of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer and matrix metalloproteinase 2 in epithelial ovarian cancer. Tumour Biol. 2007;28:280–9. doi: 10.1159/000110426. https://doi.org/10.1159/000110426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stenzinger A, Wittschieber D, von Winterfeld M, Goeppert B, Kamphues C, Weichert W, Dietel M, Rabien A, Klauschen F. High extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer/CD147 expression is strongly and independently associated with poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:1471–81. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.10.023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan H, Ye K, Wang Z, Tang H. CD147 expression as a significant prognostic factor in differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Transl Res. 2008;152:143–9. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2008.07.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trsl.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tian L, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Cai M, Dong H, Xiong L. EMMPRIN is an independent negative prognostic factor for patients with astrocytic glioma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058069. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu W, Wang R, Liu H, Peng J, Huang D, Li B, Ruan J. Prediction of prognosis in gallbladder carcinoma by CD147 and MMP-2 immunohistochemistry. Med Oncol. 2009;26:117–23. doi: 10.1007/s12032-008-9087-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-008-9087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu XY, Lin N, Li YM, Zhi C, Shen H. Expression of HAb18G/CD147 and its localization correlate with the progression and poor prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2013;209:345–52. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2013.02.015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xue YJ, Lu Q, Sun ZX. CD147 overexpression is a prognostic factor and a potential therapeutic target in bladder cancer. Med Oncol. 2011;28:1363–72. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9582-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-010-9582-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang M, Yuan Y, Zhang H, Yan M, Wang S, Feng F, Ji P, Li Y, Li B, Gao G, Zhao J, Wang L. Prognostic significance of CD147 in patients with glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2013;115:19–26. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1207-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-013-1207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang X, Dai J, Li T, Zhang P, Ma Q, Li Y, Zhou J, Lei D. Expression of EMMPRIN in adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary glands: correlation with tumor progression and patients' prognosis. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:755–60. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.08.008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu YH, Morales J, Feng L, Lee JJ, El-Naggar AK, Vigneswaran N. CD147 and Ki-67 overexpression confers poor prognosis in squamous cell carcinoma of oral tongue: a tissue microarray study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;119:553–65. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.12.022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang C, Tu Z, Du S, Wang Y, Wang Q. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase 2 and extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer are unfavorable postoperative prognostic factors in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;16:47–53. doi: 10.1007/s12253-009-9186-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12253-009-9186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao S, Ma W, Zhang M, Tang D, Shi Q, Xu S, Zhang X, Liu Y, Song Y, Liu L, Zhang Q. High expression of CD147 and MMP-9 is correlated with poor prognosis of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) patients. Med Oncol. 2013;30:335. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0335-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-012-0335-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhong WD, Chen QB, Ye YK, Han ZD, Bi XC, Dai QS, Liang YX, Zeng GH, Wang YS, Zhu G, Chen ZN, He HC. Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer expression has an impact on survival in human bladder cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2010;34:478–82. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2010.04.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhong WD, Liang YX, Lin SX, Li L, He HC, Bi XC, Han ZD, Dai QS, Ye YK, Chen QB, Wang YS, Zeng GH, Zhu G, et al. Expression of CD147 is associated with prostate cancer progression. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:300–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25982. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.25982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhong X, Li M, Nie B, Wu F, Zhang L, Wang E, Han Y. Overexpressions of RACK1 and CD147 associated with poor prognosis in stage T1 pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;20:1044–52. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2377-4. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou Q, Zhu Y, Deng Z, Long H, Zhang S, Chen X. VEGF and EMMPRIN expression correlates with survival of patients with osteosarcoma. Surg Oncol. 2011;20:13–9. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2009.09.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu S, Chu D, Zhang Y, Wang X, Gong L, Han X, Yao L, Lan M, Li Y, Zhang W. EMMPRIN/CD147 expression is associated with disease-free survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Med Oncol. 2013;30:369. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0369-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-012-0369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu S, Li Y, Zhang Y, Wang X, Gong L, Han X, Yao L, Lan M, Zhang W. Expression and clinical implications of HAb18G/CD147 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2015;45:97–106. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12320. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.12320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davidson B, Goldberg I, Berner A, Kristensen GB, Reich R. EMMPRIN (extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer) is a novel marker of poor outcome in serous ovarian carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:161–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1022696012668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Y, Xin T, Jiang QY, Huang DY, Shen WX, Li L, Lv YJ, Jin YH, Song XW, Teng C. CD147, MMP9 expression and clinical significance of basal-like breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2013;30:366. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0366-x. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-012-0366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Domschke C, Ge Y, Bernhardt I, Schott S, Keim S, Juenger S, Bucur M, Mayer L, Blumenstein M, Rom J, Heil J, Sohn C, Schneeweiss A, et al. Long-term survival after adoptive bone marrow T cell therapy of advanced metastasized breast cancer: follow-up analysis of a clinical pilot trial. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62:1053–60. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1414-x. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-013-1414-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ren F, Tang R, Zhang X, Madushi WM, Luo D, Dang Y, Li Z, Wei K, Chen G. Overexpression of MMP family members functions as prognostic biomarker for breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135544. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen PS, Shih YW, Huang HC, Cheng HW. Diosgenin, a steroidal saponin, inhibits migration and invasion of human prostate cancer PC-3 cells by reducing matrix metalloproteinases expression. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020164. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bouwman FG, Boer JM, Imholz S, Wang P, Verschuren WM, Dolle ME, Mariman EC. Gender-specific genetic associations of polymorphisms in ACE, AKR1C2, FTO and MMP2 with weight gain over a 10-year period. Genes Nutr. 2014;9:434. doi: 10.1007/s12263-014-0434-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12263-014-0434-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vigneswaran N, Beckers S, Waigel S, Mensah J, Wu J, Mo J, Fleisher KE, Bouquot J, Sacks PG, Zacharias W. Increased EMMPRIN (CD 147) expression during oral carcinogenesis. Exp Mol Pathol. 2006;80:147–59. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2005.09.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexmp.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.DeCastro R, Zhang Y, Guo H, Kataoka H, Gordon MK, Toole B, Biswas G. Human keratinocytes express EMMPRIN, an extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:1260–5. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12348959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van den Oord JJ, Paemen L, Opdenakker G, de Wolf-Peeters C. Expression of gelatinase B and the extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer EMMPRIN in benign and malignant pigment cell lesions of the skin. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:665–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iacono KT, Brown AL, Greene MI, Saouaf SJ. CD147 immunoglobulin superfamily receptor function and role in pathology. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;83:283–95. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.08.014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zheng HC, Takahashi H, Murai Y, Cui ZG, Nomoto K, Miwa S, Tsuneyama K, Takano Y. Upregulated EMMPRIN/CD147 might contribute to growth and angiogenesis of gastric carcinoma: a good marker for local invasion and prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1371–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603425. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gao J, Hu Z, Liu J, Liu D, Wang Y, Cai M, Zhang D, Tan M, Lin B. Expression of CD147 and Lewis y antigen in ovarian cancer and their relationship to drug resistance. Med Oncol. 2014;31:920. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0920-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-014-0920-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Du ZM, Hu CF, Shao Q, Huang MY, Kou CW, Zhu XF, Zeng YX, Shao JY. Upregulation of caveolin-1 and CD147 expression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma enhanced tumor cell migration and correlated with poor prognosis of the patients. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1832–41. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24531. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.24531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhong X, Li M, Nie B, Wu F, Zhang L, Wang E, Han Y. Overexpressions of RACK1 and CD147 associated with poor prognosis in stage T1 pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1044–52. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2377-4. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tsai WC, Sheu LF, Nieh S, Yu CP, Sun GH, Lin YF, Chen A, Jin JS. Association of EMMPRIN and fascin expression in renal cell carcinoma: correlation with clinicopathological parameters. World J Urol. 2007;25:73–80. doi: 10.1007/s00345-006-0110-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-006-0110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jia L, Wei W, Cao J, Xu H, Miao X, Zhang J. Silencing CD147 inhibits tumor progression and increases chemosensitivity in murine lymphoid neoplasm P388D1 cells. Ann Hematol. 2009;88:753–60. doi: 10.1007/s00277-008-0678-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-008-0678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pan Y, He B, Song G, Bao Q, Tang Z, Tian F, Wang S. CD147 silencing via RNA interference reduces tumor cell invasion, metastasis and increases chemosensitivity in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:2003–9. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1729. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2012.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao Y, Shen L, Chen X, Qian Y, Zhou Q, Wang Y, Li K, Liu M, Zhang S, Huang X. High expression of PKM2 as a poor prognosis indicator is associated with radiation resistance in cervical cancer. Histol Histopathol. 2015;30:1313–20. doi: 10.14670/HH-11-627. https://doi.org/10.14670/HH-11-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.