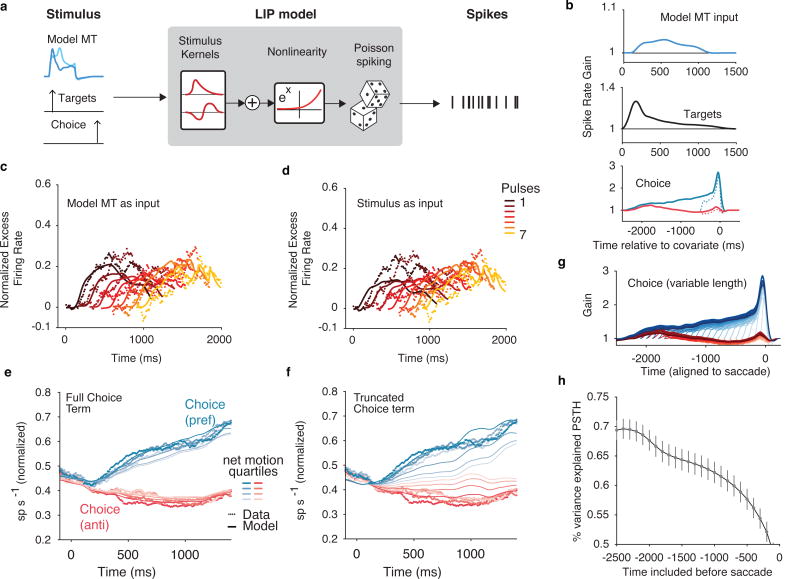

Figure 5.

LIP encoding model requires choice terms to capture response dynamics. (a) LIP model schematic. Simulated MT, target onset, and saccade times are passed in as temporal signals to a GLM fit to LIP spike trains. (b) Population (n=104) average temporal kernels expressed as impulse response (in units of spike rate gain) by exponentiating the filter outputs. (Top) Spike rate gain in response to an early pulse in the preferred direction of the LIP neuron. (Middle) response to the onset of the targets. (bottom) acausal response to choices into the RF (blue) and out of the RF (red). Dashed lines represent the temporally truncated terms that generate the PSTH in panel f. (c) Pulse-triggered average (PTA) of the data (dots) compared to the model (lines) using realistic stimulated MT for each of the seven pulses (n=104). (d) Same as in c for an LIP model that receives the stimulus as input. The failure of this model in accounting for LIP’s responses to early pulses highlights the importance of MT’s response dynamics. (e) PSTH for the data (dots) superimposed with the model (lines) including the full choice terms in b. (f) PSTH for the data (dots) superimposed with the model (lines) using truncated choice terms. (g) Choice kernels truncated at 100ms steps shows that there are still nonzero weights even 2 seconds before the saccade on each trial. (h) PSTH variance explained for different length choice kernels (shown in g). Error bars indicate ±1 s.e.m.