Abstract

In Ireland, men’s health is becoming a priority. In line with global trends, indicators of poor mental health (including rates of depression and suicide) are increasing alongside rates of unemployment and social isolation. Despite the growing awareness of men’s health as a national priority, and development of the first National Men’s Health Policy in the world, there is still a concern about men’s nonengagement with health services. Health and community services often struggle to appropriately accommodate men, and men commonly avoid health spaces. A growing body of literature suggests that a persistent lack of support or resources for service providers contributes to their inability to identify and meet men’s unique health needs. This study aims to provide further insight into the ways in which this gap between men and health services can be closed. Semistructured, qualitative interviews were conducted with nine project partners (n = 9) of a successful men’s health program in Dublin. Interviews captured reflections on what processes or strategies contribute to effective men’s health programs. Findings suggest that gender-specific strategies—especially related to community—engagement and capacity building—are necessary in creating health programs that both promote men’s health and enable men to safely and comfortably participate. Moreover, including men in all aspects of the planning stages helps ensure that programs are accessible and acceptable for men. These findings have been operationalized into a user-driven resource that illustrates evidence-informed strategies and guiding principles that can be used by practitioners hoping to engage with men.

Keywords: health promotion and disease prevention, community outreach, health awareness, health communication, men’s health interventions

Introduction and Background

Men’s health has emerged as a prominent concern in Ireland in recent years at a research, policy, and advocacy level (Richardson, 2013). In light of the recent recession, increasing rates of unemployment and suicide, particularly among lower socioeconomic groups of men, have caught the attention of policy makers and health practitioners alike. A report from the Institute of Public Health in Ireland (2011) documents strong ties between the recession and unemployment, and subsequent changes in mental health, alcohol consumption, self-harm, and suicide in men. Negative impacts on men’s health, as well as opportunities for social engagement, community participation, and having a positive sense of self are commonly attributed to the recession (Institute of Public Health in Ireland, 2011). Consequently, men who experience isolation, unemployment or low incomes, low levels of education, and adverse mental health are less likely to engage with health services or health-promoting practices; they are often classified in Ireland as “hard to reach” (Carroll, Kirwan, & Lambe, 2014). In brief, men who are at the highest risk of adverse health outcomes are also the least likely to engage in health services.

To address the unique challenge of engaging men in health programs or services, policy in Ireland is shifting to create a climate that is more conducive to health promotion initiatives for men. While globally there has been a shift toward community-based health care, unique to Ireland is the first national policy that specifically prioritizes men and men’s health needs at a policy level (Richardson & Carroll, 2008). The policy specifically addresses the need for integrative health and community development strategies that promote and capitalize on community capacity, and position men’s health within synergistic partnerships between and among sectors and policies. Despite the emergence of some promising community-based men’s health initiatives (Richardson, 2013), many existing and emerging initiatives are slow to fully incorporate a gender lens, gender-specific strategies, and community and intersectoral collaboration into practice (Heenan, 2004). While Ireland has the policy to support innovative gender work in men’s health, there remains a significant lag between policy and practice.

Research in Ireland indicates that there are two prominent issues that contribute to a lack of service uptake by “hard to reach” or “hard to engage” men: Men are less likely to seek help or take preventative measures, and there are blatant gaps in service availability for men (Institute of Public Health in Ireland, 2011). Some research indicates that proactive engagement with health (either health services, or health-promoting practices) is not part of Irish culture or social norms for men (Carroll et al., 2014; Institute of Public Health in Ireland, 2011). Men are often socialized to embrace risk taking or unhealthy practices in an effort to prove their masculinity rather than engage in health-promoting practices, which are often discursively situated as feminine (Galdas et al., 2014; Hunt et al., 2014; Richardson, 2004). Based on their limited health-promoting or help-seeking practices, men are often deprioritized within health promotion, and often viewed as “the problem” because their health practices and attitudes are seen as antithetical to “good health” (Kirwan, Lambe, & Carroll, 2013). Narrow visibility of men’s health issues, as well as the need for specific strategies that are tailored toward men, is in part explained by a limited history of mobilization around men’s health issues (Kirwan et al., 2013). Shortcomings in available services are, in part, linked to limited knowledge of men’s health issues, and to a lack of understanding of the kind of approaches or strategies that might make services more accessible and appropriate for men (Institute of Public Health in Ireland, 2011; Monaem et al., 2007). This inconsistent skill and experience among services and service providers is often linked to men either being unable to find appropriate services or of having negative experiences of services if they do (Carroll et al., 2014; Institute of Public Health in Ireland, 2011; Monaem et al., 2007).

Commonly, men report: not being trusted or believed by service providers, not being able to find personalized care, not feeling cared for or listened to by service providers, and not finding male-friendly services (such as workplace initiatives or outreach programs in community or sport settings), which commonly encompass a more personalized approach (Carroll et al., 2014; Institute of Public Health in Ireland, 2011; Monaem et al., 2007). Shortcomings in the resources and supports available to service providers are also noted in the literature as barriers to providing meaningful and effective services for men (Carroll et al., 2014; Coles et al., 2010; Heenan, 2004; Kirwan et al., 2013; Monaem et al., 2007; L. M. Robertson, Douglas, Ludbrook, Reid, & Van Teijingen, 2008; S. Robertson, Witty, Zwolinsky, & Day, 2013). Trends in the literature suggest that key challenges result from: inaccessible resources, publication bias, poor channels of communication within and between organizations, and limited and/or problematic emphasis on men and men’s health within available resources (Coles et al., 2010; Heenan, 2004; Kirwan et al., 2013; L. M. Robertson et al., 2008; S. Robertson, Witty, et al., 2013). Specifically, there is a paucity of resources or tools for service providers that highlight strategies for engaging with men, integrating community development or engagement strategies into health promotion, and building meaningful partnerships (Coles et al., 2010; Heenan, 2004; Kirwan et al., 2013; L. M. Robertson et al., 2008; S. Robertson, Witty, et al., 2013). These factors also further contribute to and result from the lag between policy recommendations and changes in practice.

Despite these challenges, programs are emerging in Ireland that reimagine health spaces for men. The Men’s Health and Wellbeing Program (MHWP) in Ballybough, Dublin is one of several programs that has reported significant achievements in both attracting and engaging men in a health promotion program (Byrne, 2013). The MHWP offers groups of about 30 men access to health information sessions, cookery classes, health checks with nurses, and football/fitness training over 10 weeks (Byrne, 2013). Men are interviewed and screened prior to joining the program encouraged to maintain their participation through one-on-one check-ins with program staff. At the time of publication, the program was in its fifth year, with approximately 250 men having completed the program. The program’s inventive partnership model allows men—who indeed fall into the “hard to reach” bracket—to engage in health-promoting activities through an array of activities or access points tailored to the target community, including health screening, fitness and football training, cookery, and health information sessions (Byrne, 2013). While there are several other recent examples in Ireland of effective engagement with men (Richardson, 2013), there is little evidence available that demonstrates “how” this work can be done, which has resulted in a dearth of supports or resources for prospective men’s health service providers. As such, there are calls within the wider literature for an investigation into the “active ingredients” that make health programs or interventions acceptable and accessible to men (Galdas et al., 2014, p. 20; Monaem et al., 2007). Thus, this study aimed to answer the question: What strategies or mechanisms contribute to meaningful program/service development and delivery for men. Subsequently, this article aims to provide insight into the ways in which a gender-specific focus contributes to meaningful and effective practices in men’s health.

Method

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the appropriate institute’s research ethics committee prior to the start of this project. As this study was concerned with the experiences of working collaboratively on the MHWP, partners of the program were identified as the target sample. As a courtesy to the partners, the MHWP coordinator identified prospective participants, contacted them with an in initial e-mail describing the details of this study, and introducing the principal investigator (PI). The PI then followed up with prospective participants, supplied additional study information, and when applicable, arranged interview times. Prospective participants were invited to partake in the study with the understanding that this was their opportunity to reflect on their work; no formal compensation was provided for their contributions. Nine one-on-one, semistructured, qualitative interviews (20-45 minutes in length) were conducted with key representatives from all of the partner organizations, and a selection of interested session facilitators (n = 9). Of the participants, four were female, five were male, three were representatives of partner organizations, three were session facilitators, two were members of the Community Center, and one was a coach. Prior to the interviews, participants were given comprehensive study information sheets, and then provided written consent. To ensure confidentiality, interviews took place in private settings (e.g., offices, meetings rooms, etc.). The PI was also invited to observe the program. Observations and informal conversations with coaches and session leaders present on that day were recorded in field notes, and later used to inform and add context to the data analysis process.

All interviews were digitally recorded and summarized using an iterative listening process with key passages and quotes transcribed verbatim. Once summaries were reviewed and deidentified, all digital recordings were securely deleted. Participants were then assigned a number to ensure anonymity from both the general population and one another. Anonymous summaries were then coded using grounded theory. In line with this approach, and key strategies as articulated by Corbin and Strauss (1990) and Auerbach and Silverstein (2003), summaries were coded iteratively using open and comparative coding techniques by two of the authors. Summaries were scanned individually by two of the authors section-by-section to identify repeating topics or themes and key language first within and then between each document. After summaries were coded, a complete list of themes was developed and compared. Where language and interpretations of the data differed, the authors negotiated similar definitions and came to one comprehensive code list. The first author then used this list to revisit all documents. This was done to ensure that analysis between authors was consistent and also that emerging codes and themes from the last transcript were considered while reviewing the first. Themes were then organized into major and subthemes, with some topics (i.e., gender) cutting across or linking several ideas. Theme memos and conceptual maps (featuring evolving relationships between themes) were developed iteratively in the analysis and writing stages to account for emerging or changing patterns and relationships between topics. In all, the authors engaged in four rounds of coding and five rounds of conceptual mapping. All authors then worked collaboratively to put together drafts of the article. Input from all authors was used to create the final conceptual framework and manuscript.

Findings

In interviews, participants reflected on their role in the MHWP partnership and in developing/delivering the program. Most reflections centered on participants’ experiences of using gender-specific approaches to address men’s well-being. Specifically, participants commented on methods for: addressing gender, working in partnership, and developing and delivering programs. Their accounts of the MHWP were organized accordingly, and are presented in this section with emphasis on strategies for practice.

Addressing Gender

All of the participants in this study noted that having a specific focus on men was an integral part of the program’s appeal and success, but was also challenging. Largely, participants reflected on the difficulty of appealing to men through a health lens and getting men to commit to behavior or lifestyle changes. These reflections emerged against a backdrop of more deep-rooted sociocultural and gender norms, which were often seen as disconnecting men from health. In particular, many participants perceived that in matters of health, men commonly, “can’t be bothered,” “are fearful,” “leave health problems for way too long,” “respond to the well-being of others,” or “don’t speak about their health.” Participants identified the sociocultural expectations for men to be “strong,” disinterested or passive in their self-care, quiet, independent, or emotionally “closed.” As a way of addressing and challenging these masculine expectations, the coaches responsible for the fitness training discussed their intentional decisions to prioritize team building, group encouragement, and collaborative work over competition or individual success. Similarly, health session facilitators emphasized the importance of interactive sessions that facilitated discussion, sharing, and questioning to counter the notion that men do not talk.

It is an illustration of how together we can—as men—stop working in competition with each other and instead learn a new paradigm, where we can work together as greater than the sum of its parts. (Participant 6)

Men, we have a huge capacity for intuitive intelligence. But, as men, we have never been told that we have that. So if you could learn that early or in mentoring or group settings, it would have a huge impact on the gender conditioning of: don’t talk, don’t show alarm, don’t show loss always be a provider, always be strong. [ . . . ] We’ve never been provided with a language or opportunity to even begin unpacking that—and it can be really impactful on men’s lives and relations, and joy. (Participant 6)

Participants also recognized how the cookery instructor, football coaches, and health session facilitators actively challenged more traditional gender norms or stereotypes through their own practice or lived experience. They acknowledged that facilitators all embodied characteristics that afforded them a certain sense of credibility among men, while simultaneously challenging certain masculine ideals such as staying away from the kitchen, abstaining from conversation, or avoiding collaboration/teamwork.

Indeed, many participants observed several cohorts of men cycle through the program and reflected both on the wider impact of the program on the men’s lives and broader ripples within the community. Participants noted that the program was a catalyst for many men to begin questioning or challenging certain gender norms or stereotypes and, as a result, for reframing aspects of their own gendered identities. For example, participants noted that cooking skills affected men’s roles in and relationships with their families, specifically in terms of being more engaged with their families, preparing meals together as a family, and feeling more comfortable and able to take on more nurturing roles. Other participants similarly noted that men were able to sustain friendships outside of the program and continue that sense of camaraderie and teamwork within the community.

Some of them said that they might never have cooked or some might have kids and would be able to go and cook a meal with their kids, and for them, that experience is so empowering. (Participant 8)

Participants also noted the challenges in tackling aspects of gendered identity that were seen as being deeply enmeshed in other aspects of identity or personal history. In particular, men who were regarded as more socially isolated and/or estranged from formal services (typically unemployed men) were also deemed to be harder to engage and thus a priority target group for the program. Participants recognized the importance of addressing more deep-rooted barriers faced by those men whose past experience of state systems and services (e.g., education) had been largely negative and inevitably mitigated against them seeking out formal settings or engaging with others in an education context. Nevertheless, many participants saw the program’s potential as a catalyst or starting point for challenging gender norms and stereotypes, and in a way that paid due regard to the wider context of men’s lives.

Men certainly have told me that they tend to keep things to themselves and not talk about things. [ . . . ] This program has provided a forum and a safe space where they have been able to open up and be kind and caring of their needs and talk about or discuss things [ . . . ] It has given permission to challenge that stereotype that men have to tough it out. (Participant 7)

Some people would be quite open and comfortable talking to a woman, and others would feel very vulnerable opening up because they’re the hard man from the inner city. [ . . . ] And for some people it’s so culturally endemic not to talk. You’re not gonna come into a room and tell people it’s good to talk, and they’re going to talk. You have to be realistic. (Participant 8)

While all participants saw gender as an important component of the program, there was debate as to whether gender-specific strategies were a necessary starting point for engaging men. Some participants emphasized a more person-centered or client-centered approach, and prioritized specific strategies for engaging men around other areas of identity such as socioeconomic status, specific health issue(s) or diagnoses, housing, employment status, or education level. It was not therefore a question of choosing different strategies for engaging men versus women, but rather tailoring strategies to specific contexts. As well as endorsing a more subtle or “sideways” approach to health, participants also stressed that, when working with men, safe and acceptable spaces, approachable facilitators, and tailored content were important strategies to consider.

Working in Partnerships

In all interviews, participants quickly equated the strength of the program to the strength of the partnership model. Specifically, participants recognized that working in partnerships led to meaningful community engagement, greater accountability and transparency, and a greater pool of resources and expertise to draw on in the program. In deeper reflection on strategies related to developing impactful partnerships, participants reflected on valuing community involvement, building sustainable relationships, establishing common objectives, allocating roles and responsibilities appropriately, and promoting leadership as key factors.

Partnerships allow us to be greater than the sum of our parts [ . . . ] I think it is important to bring the different disciplines together that has both the left brain and the right brain, the yin and the yang, that informs the practice and becomes part of the deliverable—so we can all bring our intelligence and practice and experience working with men over the years and all of us together can create something that is good, clear, ethical, and sustainable. (Participant 6)

Participants emphasized that effective and meaningful work with men needed to be deeply rooted in the community. They noted that gaining insights from men in the community about their health priorities, and identifying what types of programs or services they would want was a critical first step. Participants who were part of statutory or corporate organizations noted that partnering with community organizations was an effective way for them to tap into this insight, overcome a potential history of distrust, and establish a sense of trust, “street cred,” or “integrity” within the community. Moreover, participants noted that an organization that was “in tune” with the community was better placed to serve the needs of that community.

If we want to get men in, then we need to ask men what they want rather than presuming certain things [ . . . ] to say, “Look if we want to engage men, what do we do, what are your thoughts on this?” (Participant 7)

The [Community Center] themselves seem to be very well rooted in that community and well known. I would think that is a core element to get right. So it isn’t just a van pulling up for an hour a week, it is a Center that is a very accepted part of the community, it is rooted in the tradition of that area, and well known—the staff are well known. I think that is a huge piece. (Participant 4)

Participants were careful to acknowledge the skills, expertise, and knowledge of past program participants, who, in providing feedback, and encouraging others to join, contributed as much, if not more importance, to the success of the program than the behind-the-scenes work done at an organizational level. Some participants did not differentiate between program participants and organizational partners and recognized that meaningfully engaging with community participants, showing respect and appreciation for their involvement, and incorporating their feedback and ideas on a par with anything contributed by other partners, was instrumental to the program’s inception and longevity.

We are very much a part and parcel of the community, and the community knows this. So we’ve always used the community as a touchstone. We have always developed initiatives with reference to them rather than doing things and then saying come on in. [ . . . ] So that collaborative approach and relationship is critical because it is not only reflecting the interests of the community, but it is building ownership that the community feels that they are part of it and have a say in what’s going on. It is being done with them as opposed to them or for them. (Participant 7)

Building strong relationships between partners was noted as having significantly contributed to the success and endurance of this partnership. Participants acknowledged that aligning personal or organizational missions, identifying available skillsets and expertise, setting common goals, and establishing trust were instrumental processes in building sustainable partnerships. In explaining their motivation to become program partners, participants all identified the significance of having parallel or overlapping organizational missions. Some participants suggested that the partnership’s natural fit with their corporate social responsibility model, or wider organizational ethos was an opportunity to simultaneously advance the credibility and reputations of both the program and their organization. Consequently, the reputation of the program attracted fellow practitioners who got involved in the partnership at a later stage. Thus, participants suggested that partnerships can be both advantageous and opportunistic.

We set out a plan and a series of objectives that we got buy-in for at the very outset. So what we were looking to achieve corresponded with what the partner agencies had as well. (Participant 7)

For us, it fits into our corporate reputation and responsibility of work [ . . . ] it’s our responsibility to help vulnerable groups in our communities, and we’re happy to do it. (Participant 4)

Participants similarly reflected that the sustainability of their partnership was a result of having shared principles and values. Work ethic, commitment, open-mindedness, professionalism, and ambition were cited as the core values that molded this partnership into a cohesive and enjoyable unit and that drove the program forward. Participants noted it was important not just to share these core values, but achieve a balance whereby everyone was committed to the project and had the professionalism, self-awareness, and mindfulness to avoid being territorial and, when appropriate, to allow another partner, who might be better qualified or better suited, to step in and lead on a particular aspect of the program. Having clearly defined roles and responsibilities within the partnership that corresponded to partners’ unique skillsets, was a strategy recognized as allowing them to work optimally within their capacity, avoid conflict, and broaden the overall pool of collective resources.

The values are the first thing. The value of being committed, the values of being able to listen without prejudice of others, and work to a consensus when possible. (Participant 9)

The model is very simple: everyone brings something to the table. [ . . . ] Everyone has a responsibility to bring a certain skillset or enable a particular part of the program. . . . So the expectation is just one of delivering and not letting them [other partners] down. (Participant 4)

Given that the partnership experienced changes in membership over the years, participants also attributed the sustainability of the partnership to consistent communication, continued passion for the project, wariness against complacency, selection and maintenance of the right type and number of partners, and flexibility with organizational turnover.

In terms of ongoing maintenance of the relationship, it is keeping people informed, maintaining awareness of common objectives and commonalities of purpose, it’s having people who are comfortable within that space and are passionate and want to do this kind of work. (Participant 7)

It’s not the same set of people we started out with—we’ve moved on and some others have moved on, and that’s okay too. (Participant 7)

Good, clear leadership was seen by all participants as instrumental in both driving the program forward and sustaining the partnership. The Community Center was seen as the primary partner to which all others turned to for guidance. Members of the Community Center “led” by being responsible for all of the administrative and communication work, engaging the community, setting program priorities, finding space to house the program, being present during each program session, and gathering feedback from program participants and facilitators. The program coordinator was recognized by all participants as the primary driving force of the program and partnership alike.

You also need a really strong coordinator. So I presume at the start you would need a lot of that face-to-face time, and meetings to get everything up and running. But over time, they become less and less important because it is up and running, the trouble-shooting is done. People know what works well, what doesn’t, what you need more of, what to avoid. But, the [lynch]-pin is that you have a very strong coordinator who keeps everyone informed—especially if something is missing or off. (Participant 5)

Participants commented that the program coordinator’s knowledge of the community and program participants, as well as her passion, drive, and ambition for the program, were the defining aspects of her leadership. Many participants explained that the program’s success was inextricably linked to having one central leader, as distinct from a more flattened hierarchy model with shared responsibility. Consequently, some participants brought up concerns about the sustainability of the program should the program coordinator discontinue her involvement.

Despite recognizing the strength of this partnership model, participants also identified external barriers that they felt added tension to the partnership and threatened its longevity. In particular, participants commented that financial austerity (particularly in light of a harsh economic climate), led to uncertainty of the future of the program, and in particular whether they would be able to secure funding and necessary resources from 1 year to the next. This was of particular concern for partners who were responsible for financing the program.

The only thing is that they are poorly resourced. So being able to sustain from one program to the next is quite challenging, so it would be great if they could secure some kind of national funding that can cover the entirely of the project, because it is always dependent on how they can they get the funding for the next course. (Participant 4)

Participants also suggested that prioritizing men’s health, especially for older men, was challenging both in terms of overcoming undercurrents of disenchantment or apathy that were seen as typically characteristic of a marginalized community, and in getting buy-in from potential partners and political actors. This led to disinterest in the program from some prospective participants and organizational partners or funders.

With meetings like this, and particularly in this area, there is always a sense that nothing happens here, or we’re left out. People don’t deliver on what they say—so we were conscious of that too. That people just don’t get involved. And we were very aware that we needed successes and that things would happen that were perhaps generating a degree of hope and possibility. (Participant 7)

Although they spoke candidly about the challenges of working in partnerships and their concerns for the future, most participants remained confident that the strategies they used were sufficient in building and maintaining relationships. They stressed that partnerships must be an intentional and strategic process of bringing together complementary people, perspectives, and goals; as such, partnerships can be discontinued or avoided should they no longer enhance a common mission. Thus, participants maintained that in partnerships there must be a balance between fluidity or evolution, and consistent commitment to a common goal.

Program Development and Delivery

Participants spent a significant amount of time discussing the different aspects of program development including content and focus, outreach and participation, creating a “hook,” facilitation, and reflective practice. Participants noted that while each element was distinct, the cumulative effect of having strategically and intentionally thought out each aspect contributed to a strong overall program. All participants noted the importance of avoiding shortcuts or the temptation of a one-size-fits-all template. Participants reflected on the program as an evolution or work in progress, based on feedback from community partners, rather than being seen from the outset as a fait accompli.

A lot of people will want to lift something off the shelf and implement it, and that is fine if it is something like a training course on presentation skills. But for a program that deals with lifestyle change or behavior change—a program like this—you really have to go through all the steps. [ . . . ] I know that process isn’t what people want all the time, but it is important to not shortcut these processes of identifying needs and stakeholders. (Participant 4)

Taking holistic and social determinants approaches to health, and incorporating diverse elements, were seen as the major strengths of the program’s content and appeal. Participants observed that addressing more diverse aspects of wellness or quality of life (as distinct from direct focus on “health”), created a more approachable and meaningful space to engage men.

I suppose the strength is the build-up and the cumulative effect of the sport, and the cooking, and belonging to a group to enable men to take responsibility for their health and wellbeing and I suppose that cumulative effect is more powerful than anything. (Participant 8)

Health was respectfully there. And again it was about health and wellbeing. I think health, as a brand, is very damaged in Ireland . . . I think when working with men, it is important to talk about wellbeing or wellness, or finding new words that are less contaminated. (Participant 6)

Participants recognized that buy-in or support from men in the community was indispensable in developing an effective program, and prioritized the investment of time and energy into developing solid strategies for outreach and participation. It was felt that effective program outreach meant being visible or present in the community, meeting face-to-face with people in common spaces, and promoting word-of-mouth or peer-based recruitment. Participants also saw the importance of addressing shortcomings of other health programs that were exclusive, limited in number, geographically inaccessible, or targeted at the worried well.

A lot of activities around health promotion, as much as we would like to think otherwise, they are middle-class oriented. If you are reading the right papers, or on the right internet site, or in the right doctor’s surgeries, listening to the right radio station, watching the right TV channels, you might get those health promotion messages and that, but unfortunately we live in a very often inequitable society and not everyone will have access to that. (Participant 4)

Participants also noted that outreach did not end once participants enrolled in the program; rather, it was a commitment to a continuous process of drawing people in, creating spaces and opportunities for men to participate, providing individual or tailored support, facilitating positive peer dynamics, and promoting leadership. Some participants reflected on emerging leadership within the community, and suggested that men who had previously been engaged in the program could become “champions” or “ambassadors” within the community and further promote the program by sharing their skills and experiences.

We engage people where they want to be engaged. So we are flexible and weave things around them. But once people are here and we can build a relationship and trust—that seems to keep people engaged with us. (Participant 8)

Personal contact is highly important in any work that involves reaching out to men. [ . . . ] So our work is about the person—we will get to know each one who comes through and what their circumstances and needs and issues are. And in so far as we can, we will do things to support and assist people to move forward in their own situation. (Participant 7)

In addition to conducting meaningful outreach, participants also noted that there needed to be an enticing “hook” that not only attracted men to the program but also sustained and validated their involvement over time. Given that health can be a taboo topic for many men, participants explained that a hook needed to have a sense of social currency or a reputation that would justify and make engagement in a health program acceptable. Many participants linked this to the notion of “branding” or “celebrity” suggesting that if a health program came from a reputable or attractive source, it was more likely to be taken seriously and sought after by men.

Initially to get people into the group in the start is quite difficult. So I think with this, the big thing is that it’s run in conjunction with the [football club]. So that has a big impact that it’s something that they recognize as a brand or as something that they’ve known all their lives. So going into a group that they might feel quite apprehensive about or quite nervous about, I’d say it makes it that little bit easier because if its run by them it must be good, it must be useful. (Participant 9)

The initial hook was being able to say to my friends that I was playing football with the [football club] guys on Wednesday, so I think that would be really good currency down at the pub or with friendships. (Participant 6)

Participants recognized that intentional facilitation strategies—addressing power dynamics, creating safe and inclusive spaces, operationalizing health information into plausible actions, and fostering meaningful conversations—were used to influence both lifestyle/behavior change and what were seen as more fundamental personal, emotional, and social changes. Participants discussed the importance of addressing safety and power from the onset to make spaces safe; often facilitators named these issues and positioned themselves within rather than distinct from the group. Some participants subsequently noted that meaningful facilitation was more about the “how” than the “what”: for example, how to apply learning into actionable and feasible strategies within the men’s own lives. Participants explained that this proactive approach also enabled men to conceive of mechanisms of support to help achieve health goals as a team rather than individually (i.e., walking groups). Participants discussed the importance of integrating conversational, storytelling, and team-building approaches into health, cookery, and football/fitness sessions alike to address broader sociocultural and gender norms that affect men, and ultimately make health spaces and topics acceptable.

I’d always sit down. I’d always sit in the group, so we’d have the chairs in a group, and I’d sit within the group. Maybe I’d be placed a little bit [outside]—but not standing up to present. So I’d try to make it as informal as possible and make them feel like they could have a conversation. (Participant 9)

I will use “I” statements and say, “For men, I know when I go into a room I want to feel safe and know that I am treated safely” and I might say that to a group so that it is important that I know you feel safe, and you get the shape of me and know that I’m not going to hurt them. So I think it is important to ask men what would make it safe, what are the things that make you think of safety in your own lives [ . . . ] So it’s not a gimmick, you are mentoring men around learning what for them is a toolkit when they are in any clique—so they can identify what makes them feel safe, and they can articulate that. (Participant 6)

Facilitators also described particular challenges around program development and delivery. In particular, participants suggested that building evaluation or feedback loops into the program’s structure was both important and difficult to maintain as the program grew and changed hands.

It would be great to evaluate what I do—but it’s the one thing we don’t get to do because it is a one-off session and it is a really casual conversation, it’s really informal. (Participant 9)

On a more personal level, participants revealed that leading sessions could be quite challenging. For some, engaging with men around health issues meant having to confront their own experiences; for others, it meant trying to balance multiple responsibilities. Working with men meant also “working on fumes” with limited supports or resources for their own well-being as staff. Thus, many participants stressed that self-care was important to consider as well, in order to sustain their own involvement in the program.

My sense is, though, that men’s health and men’s work is really hard. And development work is very challenging. And a lot of us feel very unskilled, don’t want to ask the questions, and certainly—if we are honest with ourselves—don’t want to hear the answers because there is a real fucking day’s work in the answers. [ . . . ] What do front-line people do with all those feelings, and all those feelings of being inadequate? I’ll tell you what we do, eventually, we stop asking the questions, because it’s too painful. (Participant 6)

Participants shared a wide range of experiences and often felt both invigorated and challenged by the intentional approaches used to cater to men. While no participants held firm beliefs as to one right way of addressing men’s health issues, many kept referring back to the importance of involving the community of interest as much as possible, and working to continually draw men in and keep them engaged. Participants remained optimistic that with continued support (either from partners or organizations) and appropriate resources, they could sustain inventive and holistic health programming for men.

Discussion

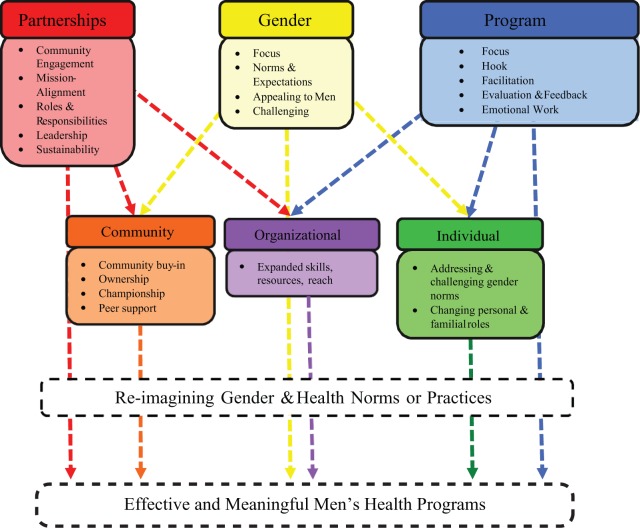

From their reflections on how to address gender, facilitate effective partnerships, and develop/deliver an impactful program, participants alluded to capacity building at individual, partnership, and community levels as a part of both the process and outcome of positive engagement with men (see Appendix 1). The primary objective of the program was to facilitate positive health and lifestyle changes among men by equipping them with appropriate and useful health information, fitness training, and cooking/healthy eating skills. Interestingly, participants suggested that the program additionally increased men’s capacity to confront gender norms and take on more active roles at home and in the community. Participants discussed this capacity building in relation to processes or strategies used within the program and partnership development that both validated men’s existing skills, knowledge, and values, and created opportunities for men to develop new abilities or confront their own long-standing beliefs. Similarly, participants reflected on their own personal/professional development, and discussed increasing their capacity to engage with communities and with men.

Findings suggest that, at an individual level, specific strategies or aspects of the program made men feel safe and comfortable by valuing and validating their lived experiences and worldviews, while still creating a platform to build new skills and increased confidence to confront gender norms or expectations. Based on community feedback and priorities, the program picked a strategic hook—football—to draw men in, capitalize on their existing values or interests, and make men feel more comfortable to address more taboo topics like health and cooking. Participants’ reflections indicate that this strategy made men feel comfortable in and excited about the program. This finding echoes evidence from other health promotion projects for men that similarly suggest the importance of not framing projects directly as “health” (S. Robertson, Witty, et al., 2013; S. Robertson, Zwolinsky, et al., 2013). Football often has an elite, acceptable, or desirable status, which helps make the health component of programs also acceptable to men (Hunt et al., 2014; Pringle et al., 2013). Integrating a feminized topic (like health) with an acceptable masculine interest (like football) decreases the risk that men may experience when associating with or being recognized within a health space (Whitley et al., 2007). Fully incorporating and realizing men’s ideas and feedback also set a particular tone for the program in which men’s existing knowledge was valued and validated on par with contributions from other partners. The importance of involving men in community health programs from the point of inception, and genuinely listening to them as projects develop, has been noted in previous evaluations of such initiatives (S. Robertson, Zwolinsky, et al., 2013) and in other work reviewing what makes for successful health promotion interventions for men (S. Robertson, Witty, et al., 2013).

Creating safe spaces, facilitating discussion-based or conversational learning, picking facilitators who practice what they preach, promoting action-oriented health information, and fostering collaboration or team building (rather than competition) also emerged from the data as strategies that allowed men to engage with topics in health and gender in meaningful ways. Previous work suggests that creating opportunities for casual or conversational learning is important and often overlooked for men (Carroll et al., 2014; Galdas et al., 2014). Specifically, men might distance themselves from discussions because of the presumed “touchy-feely” or “feminine” environment, and service providers might choose a different or more structured/orderly format based on stereotypes that men are rational or logical (Carroll et al., 2014; Galdas et al., 2014). Findings from this study along with boarder literature suggest that men often benefit from having the opportunity to engage in a more spontaneous or laid-back environment (Carroll et al., 2014; Galdas et al., 2014; Hunt et al., 2014). Bringing men together in a group environment challenges them to confront the notion that sitting and talking is for women (Coles et al., 2010). Furthermore, participants indicated that men benefitted from informal or side conversations that took place within health sessions as well as the broader sense of team building: both of which facilitated openness and trust within the group. Peer support and camaraderie is both beneficial and attractive to men (Galdas et al., 2014) as it transcends superficial notions of “team spirit” to foster ownership within and of the program (Hunt et al., 2014). Findings also suggest that proactive strategies that operationalized health and fitness information made health concepts more accessible and feasible for men. This strategy allowed men to conceptualize and integrate changes into their own lifestyles, and created opportunities for men to set group goals or strategies and follow-up with changes outside of the program (i.e., walking groups). Broader literature likewise suggests that active rather than passive participation, including an emphasis on problem solving, can help men feel more in control and comfortable giving and receiving support as it is a “by-product” of another shared activity (Galdas et al., 2014; Gough, 2006). Findings also indicate that it was important to go through the process of creating safe spaces with men so that they could learn to identify or articulate what makes spaces safe, thereby enabling them to replicate these circumstances outside of the program. In this way, as others have recognized (S. Robertson, Zwolinsky, et al., 2013), the provision of such safe spaces provides time for men to reflect on their identity, including their gendered identity, generating shifts in gendered practices.

Changes in men’s individual capacity created knock-on effects or ripples within the community. Participants drew attention to the importance of fostering leadership or championship within the program in order to sustain momentum, participation, and men’s community involvement after the program ended. Pringle et al. (2013) similarly noted that the visibility of champions often helped alleviate concerns and engage men who might be hesitant to take part in formal health interventions. When men develop a sense of pride or confidence in their skill development, over time, they become more willing or able to share this learning with others (Fildes, Cass, Wallner, & Owen, 2010). This trend was noted here as participants commented on the transfer of skills within families and between friends (typically related to cooking and fitness). Some participants explained that community pubs and other social spaces also experienced change, with many regulars now sharing recipes and advice. Former program participants went on to create a community garden, which also had a profound impact on the community’s physical space, and opportunities for men to engage in community away from pub spaces. Again, this is in line with previous work on effective men’s health programs, which identifies that change extends beyond the level of the individual and has impact on those close to participants in such programs and the wider community (Robertson, Witty, Zwolinsky & Day, 2013). While it is possible that these wider changes may have been influenced by larger social changes—such as positive shifts in masculinity (Anderson, 2009) or local improvements in social and economic circumstances—the participants identified a much closer and direct relationship between these community “ripple effects” and the MHWP.

Partnerships facilitated capacity building at an organizational level as participants reflected on gaining new skills and confronting or overcoming limitations as individuals or distinct organizations. Participants widely adopted a “greater than the sum of its parts” mentality when describing how working collaboratively—especially with the community or community partners—enhanced their ability to work within and beyond their own skillsets, build a positive reputation, and equip the program with necessary resources and supports. Wider literature similarly reports that partnerships are a useful strategy to combat limited availability of resources, funding, and institutional support (Kierans, Roberston, & Mair, 2007; Whitley et al., 2007). Trends in the data suggest there was a cyclical relationship between community engagement and partnerships whereby engaging in the community enriched partnership development, and strategic partnerships with community organizations or community members enhanced community engagement. This close-knit and seamless relationship gave way to capacity building by generating greater insights into strategies for reaching and engaging men. Findings suggest that using community feedback to determine program priorities and strategies helped promote accountability, integrity, and (street) credibility. Heenan (2004) similarly suggests that being accountable to and involving the community in decision making is key to building trust, mutual respect, and avoiding a tokenistic involvement of the community that can generate frustration, suspicion, tension, and resentment. As S. Robertson, Zwolinsky, et al. (2013) have also reported, situating decision making within the community gives the program “street cred” that attracts participants and support. Similarly, using community organizations as a platform to connect community members with other partner organizations is another way to build trust, familiarity, and help men link in with other health services or organizations (Institute of Public Health in Ireland, 2011). Involving communities in identifying their own health priorities is an effective way to navigate limited funding and resources; letting prospective participants decide what is important can prevent unnecessary spending on initiatives that will not generate support or participation (Kirwan et al., 2013; Whitley et al., 2007).

When discussing their role in the partnership, many participants explained that working in men’s health is both rewarding and also challenging; they enjoyed and felt satisfied with their contribution to the men in the program, but struggled with a lack of available supports or resources. The emotional work of supporting men can be onerous as responsibilities and commitments often extend beyond standard work hours. These findings align with broader literature on emotional work in “caring professions” and occupational burnout. Those in human service professions often experience higher rates of personal accomplishment in line with intrinsic motivation or genuine interest in and care for clients; yet this emotional work and exhaustion is rarely paid much attention, and is at the core of emotional exhaustion and burnout (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002). The capacity building and partnerships at an organizational level made way for new knowledge and skills for working with men, but also created new challenges for participants who were already “running on fumes.” The training of those working in this field is therefore of great importance as a previous review of the key elements that promote success in men’s health promotion interventions has demonstrated (S. Robertson, Witty, et al., 2013).

Strategically pairing acceptable masculine activities or environments (i.e., football training and strategy-based or applied health information) with more taboo or feminized program components (i.e., health checks, cookery, and discussions) was an overall approach to this men’s health program that yielded considerable success, but is not unproblematic. Although sports are appropriate and effective avenues through which men can engage with health and other activities that challenge certain gender norms (e.g., talking as a group or cooking), it is important that care is taken to ensure that negative elements of masculinity are not replicated through these processes (S. Robertson, 2003; Spandler & McKeown, 2012). This sideways approach to health indeed creates more opportunities for men to get involved on their terms. It creates the space to use more holistic or multifaceted approaches to health, and allows a program to cast a wider net and appeal to men at different intersections of their identity; indeed, a key point of the program is that community engagement informed its design from the outset helping ensure diversity and intersectionality were considered and incorporated. Yet this strategy can run the risk of reaffirming certain norms about acceptable behaviors, interactions, activities, and environments for men. As others have noted, health promotion programs for men can often (unintentionally) recreate gender norms or hegemonic notions of masculinity by relying on assumptions or stereotypes rather than critical thinking to inform decision making (Coles et al., 2010; Robinson & Robertson, 2010). Targeting men at work, referring to men’s health in mechanical terms like “tuning up,” or creating one-size-fits-all programs for men are often unsuccessful in creating health behavior change, and can undermine men’s experiences and health-promoting behaviors (Coles et al., 2010; Smith & Robertson 2008). What is therefore significant about this program is that capacity building was strongly linked to men’s ability to confront and reimagine gender norms. Thus, this program created opportunities to overcome previous shortcomings in health promotion initiatives by encouraging men (through community feedback, team building, and conversational or active learning) to grapple with and reimagine the same gender norms that initially attracted them to the program.

Limitations

Despite the ability of this article to articulate key strategies or mechanisms for developing effective programs for men, there are limitations to this study. First, partners—even a key informant who helped recruit other partners—only identified community members who acted as both recipients and partners of the MHWP in interviews, once ethical approval was granted and data collection was well underway. As such, it was a blind spot of this project that community partners who were also recipients were unknown until data collection was nearly completed and were not contacted for participation in this study. Although the interview provided an opportunity for participants to speak candidly about their experiences—especially because a formal evaluation had already been carried out—it is possible that participants were still guarded in their responses because of their close connection to the program and to the other research participants. While participants were reminded that this study was not an evaluation and that all responses would be kept strictly confidential, it is possible that participants hesitated to share negative feedback about the program. Although it seemed that the program was an overwhelming success, it is hard to know if the perspectives shared were also inflated for the sake of sustainability of the program, and continued positive relations with the other partners.

Conclusion

This study aimed to identify the strategies or mechanisms for developing and delivering effective health promotion programs or services for men. This study suggests that gender-specific strategies are important in creating effective health programs for men. Yet this idea of gender-specific strategies or gender tailoring is still a contentious one; participants in this study had differing views on the importance of strategies just for men versus “people strategies.” Some participants recognized that in some contexts, engaging people around other areas of their identity (e.g., education level, socioeconomic status, housing, etc.) is more important than gender—though the two are, of course, not mutually exclusive. When using gender-specific strategies, it is important to consider the intersectionality of identity, and the similarities as well as difference among men in order to arrive at the most effective approaches. Findings also indicate that integrating a gender focus with strategies for capacity building (at individual, organizational, and community levels) as both an outcome of and process tied to creating and delivering programs to men, improves the accessibility, acceptability, appropriateness, and quality: key characteristics of promising practices in health promotion and human rights discourses. In doing so, more opportunities are created to critically engage with notions of masculinities and health at each step of program development and delivery. This process in turn helps prevent the common health promotion pitfall of replicating dominant ideas of masculinity and inadvertently undermining men’s ability to engage with and improve their health. These findings have been operationalized into a user-driven resource that illustrates evidence-informed strategies and guiding principles that can be used by practitioners hoping to engage with men (Lefkowich, Richardson & Robertson, 2015).

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Concept Map

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Anderson E. (2009). Inclusive masculinity: The changing nature of masculinities. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach C. F., Silverstein L. B. (2003). Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brotheridge C. M., Grandey A. A. (2002). Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of “people work.” Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60, 17-39. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne N. (2013). Investigating the impact of Men’s Health and Wellbeing Program targeted at disadvantaged men in Dublin’s inner city (Master’s thesis). National Centre for Men’s Health, Institute of Technology Carlow, Carlow, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll P., Kirwan L., Lambe B. (2014). Engaging “hard to reach” men in community based health promotion. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 52, 120-130. [Google Scholar]

- Coles R., Watkins F., Swami V., Jones S., Woolf S., Stainstreet D. (2010). What men really want: A qualitative investigation of men’s health needs from Halton and St. Helen’s Primary Care Trust men’s health promotion project. British Journal of Health Psychology, 15, 921-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J., Strauss A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 19, 418-427. [Google Scholar]

- Fildes D., Cass Y., Wallner F., Owen A. (2010). Shedding light on men: The Building Healthy Men Project. Journal of Men’s Health, 7, 233-240. [Google Scholar]

- Galdas P., Darwin Z., Kidd L., Blickem C., McPherson K., Hunt K., . . . Richardson G. (2014). The accessibility and acceptability of self-management support interventions for men with long term conditions: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Public Health, 14, 1230 Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2458-14-1230.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough B. (2006). Try to be healthy, but don’t forgo your masculinity: Deconstructing men’s health discourse in the media. Social Science & Medicine, 63, 2476-2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heenan D. (2004). A partnership approach to health promotion: A case study from Northern Ireland. Health Promotion International, 19, 105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt K., Gray C. M., Maclean A., Smillie S., Bunn C., Wyke S. (2014). Do weight management programs delivered at professional football clubs attract and engage high risk men? A mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health, 14, 50 Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Public Health in Ireland. (2011). Facing the challenge: The impact of recession and unemployment on men’s health in Ireland. Retrieved from http://www.publichealth.ie/files/file/Publications/Facing%20the%20challenge.pdf

- Kierans C., Roberston S., Mair M. D. (2007). Formal health services in informal settings: Findings from the Preston Men’s Health Project. Journal of Men’s Health & Gender, 4, 440-447. [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan L., Lambe B., Carroll P. (2013). An investigation into the partnership process of community-based health promotion for men. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 51, 108-120. [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowich M., Richardson N., Robertson S. (2015). Engaging men as partners and participants: Guiding principles, strategies, and perspectives for community initiatives and holistic partnerships. Retrieved from https://www.itcarlow.ie/public/userfiles/files/Engaging%20Men%20as%20Partners%20%20Participants.pdf

- Monaem A., Woods M., Macdonald J., Hughes R., Orchard M. (2007). Engaging men in the health system: Observations from service providers. Australian Health Review, 31(2), 211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle A., Zwolinsky S., McKenna J., Daly-Smith A., Robertson S., White A. (2013). Delivering men’s health interventions in English Premier League football clubs: Key design characteristics. Public Health, 127, 716-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson N. (2004). Getting inside men’s health. Retrieved from http://www.irishhealth.com/clin/documents/Mens_Health.pdf

- Richardson N. (2013). Building momentum, gaining traction: Ireland’s national men’s health policy – 5 years on. New Male Studies, 2(3), 93-103. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson N., Carroll P. (2008). National Men’s Health Policy 2008-2013. Retrieved from http://www.mhfi.org/menshealthpolicy.pdf

- Robertson L. M., Douglas F., Ludbrook A., Reid G., Van Teijingen E. (2008). What works with men? A systematic review of health promoting interventions targeting men. BMC Health Services Research, 8, 141 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2483970/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson S. (2003). “If I let a goal in, I’ll get beat up”: Contradictions in masculinity, sport and health. Health Education Research, 18, 706-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson S., Witty K., Zwolinsky S., Day R. (2013). Men’s health promotion interventions: What have we learned from previous programmes? Community Practitioner, 86, 38-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson S., Zwolinsky S., Pringle A., McKenna J., Daly-Smith A., White A. (2013). “It’s fun, fitness and football really”: A process evaluation of a football based health intervention for men. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 5, 419-439. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M., Robertson S. (2010). The application of social marketing to promoting men’s health: A brief critique. International Journal of Men’s Health, 9(1), 50-61. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. A., Robertson S. (2008). Men’s health promotion: A new frontier in Australia and the UK? Health Promotion International, 23, 283-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spandler H., McKeown M. (2012). A critical exploration of using football in health and welfare programs: Gender, masculinities, and social relations. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 36, 387-409. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley E. M., Jarrett N. C., Young A. M. W., Adeyemi S. A., Perez L. M. (2007). Building effective programs to improve men’s health. American Journal of Men’s Health, 1(4), 294-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]