Abstract

Background

Epidemiological evidence suggests that timing of introduction of solid foods may be associated with subsequent obesity, and the association may vary by whether an infant is breastfed or formula-fed.

Methods

We included 1181 infants who participated in the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPS II) and the Year 6 Follow Up (Y6FU) study. Data from IFPS II were used to calculate the primary exposure and timing of solid food introduction (<4, 4–<6, and ≥6 months), and data from Y6FU were used to calculate the primary outcome and obesity at 6 years of age (BMI ≥95th percentile). We used multivariable logistic regression to assess the association between timing of the introduction of solids and obesity at 6 years and test whether this association was modified by breastfeeding duration (breastfed for 4 months vs. not).

Results

Prevalence of obesity in our sample was 12.0%. The odds of obesity was higher among infants introduced to solids <4 months compared to those introduced at 4–<6 months (odds ratio [OR] = 1.66; 95% CI, 1.15, 2.40) in unadjusted analysis; however, this relationship was no longer significant after adjustment for covariates (OR = 1.18; 95% CI, 0.79, 1.77). Introduction of solids ≥6 months was not associated with obesity. We found no interaction between breastfeeding duration and early solid food introduction and subsequent obesity.

Conclusions

Timing of introduction of solid foods was not associated with child obesity at 6 years in this sample. Given the inconsistency in findings with other studies, further studies in larger populations may be needed.

Introduction

In the United States, more than 8% of 2- to 5-year-olds and 17% of 6- to 11-year-olds have obesity.1 Children with obesity are more likely to have elevated cholesterol and blood pressure levels, breathing and joint problems, and are more likely to become adults with obesity.2,3 Multiple factors contribute to development of childhood obesity,3 and though no single factor explains all obesity, understanding which factors may play a role has important public health implications.

Early infancy, particularly early nutrition, has been identified as a critical period for preventive strategies aimed at decreasing rates of obesity.4 One strategy that has been identified is increasing adherence to guidelines regarding timing of the introduction of solid foods. In previous analyses of the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPS II), we found that 40% of infants in our sample were introduced to solid foods before 4 months of age.5 Although there has been inconsistency in recent years regarding recommendations on whether complementary foods should be introduced between 4 and 6 months,6,7 or not until 6 months,8–10 most groups agree that introduction to solid foods before 4 months is too early.6–8,10

A review of 26 studies concluded that introduction of solids ≤4 months is associated with obesity, particularly among formula-fed infants.11 However, of the studies reviewed, the researchers concluded that few were large, good-quality studies. Additionally, some studies suggest that the association may differ for breastfed versus formula-fed infants.11,12 Thus, our aim, using data from a cohort of US children followed longitudinally throughout the first year of life, and contacted again at 6 years, was to assess how early introduction of solid foods (before 4 months) was associated with obesity at 6 years of age, and test for an interaction with breastfeeding status, controlling for multiple potential infant, child, and maternal confounders.

Methods

The IFPS II, conducted from 2005 to 2007, followed mothers from their third trimester of pregnancy through their infant’s first year. Infants born before 35 weeks, weighing less than 5 pounds (lbs), who were a non-singleton, or with medical conditions that would affect feeding were not eligible to participate. A cross-sectional Year 6 Follow Up study (Y6FU) was conducted in 2012 when infants from the original study were approximately 6 years old. Among eligible IFPS II participants (completed the neonatal questionnaire and not subsequently disqualified from IFPS II),13 1542 completed the Y6FU (response rate of 52%). Detailed methodology of Y6FU, including comparison of respondents to nonrespondents and to a nationally representative sample, are presented in a previously published methods article.13 Generally, participants of Y6FU were more likely to be white, higher educated, and married compared to a national sample.13

Child Obesity

With the Y6FU questionnaire, mothers were sent a measuring tape and instructions on how to measure their child’s height. They were asked to report this measure in inches, as well as to weigh their child on a scale without shoes and report the child’s weight in lbs; these measures were used to calculate z-scores of BMI (kg/m2). Child obesity was defined as age- and sex-specific BMI ≥95th percentile according to the 2000 CDC growth charts.14

Infant Feeding

IFPS II included approximately monthly postnatal questionnaires that each included a food frequency chart asking about the infant’s intake within the previous 7 days. We calculated age at introduction to solid foods as the midpoint between the child’s age when the mother reported no solid food consumption and when she first reported that her child had consumed solid foods in the previous 7 days. Solid foods included dairy foods other than milk (e.g., yogurt, cheese, and ice cream); soy foods other than soy milk (e.g., tofu, frozen soy desserts); baby cereal; other cereals and starches (e.g., breakfast cereals, teething biscuits, crackers, pasta, and rice); fruits; vegetables; french fries; meat, chicken, or combination dinners; fish or shellfish; peanut butter, other peanut foods, or nuts; eggs; and sweet foods (e.g., candy, cookies, and cake). Timing of introduction to solids was grouped into three categories: <4, 4–<6, and ≥6 months.

During IFPS II, when mothers indicated they were no longer breastfeeding, they were asked how old their infant was when they completely stopped breastfeeding or pumping milk; these data were used to categorize breastfeeding duration. We categorized infant feeding as those who received breastmilk for 4 or more months or not (never breastfed or stopped breastfeeding before 4 months).

Covariates

Maternal characteristics from the baseline IFPS II study included age (18–24, 25–29, 30–34, or ≥35 years), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other), education (≤high school, 1–3 years of college, or college), poverty-income ratio (PIR; <185%, 185–349%, or ≥350%), prepregnancy BMI (<18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, or ≥30.0 kg/m2), marital status (married, not married), and parity (primiparous, multiparous). Infant characteristics included sex, birth weight (<4000, ≥4000 g), and gestational age (<37, ≥37 weeks). Child characteristics included daily frequency of consumption of water, fruits, vegetables, and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) at 6 years.

Analytic Sample and Statistical Analysis

Data on BMI at 6 years were available for 1408 participants, of which 11 were excluded for having biologically implausible values (<–4 standard deviations from the median BMI-for-age15; the maximum BMI-for-age in our sample was 3.4, so no participants were excluded for high values). Data were missing on timing of introduction of solid foods for 89 participants, and 168 were missing data on covariates. Data were missing for more than one variable for some participants, giving a final analytic sample of 1181. Infant characteristics and prevalence of child obesity were similar among those included versus excluded from analysis. Mothers of children included in the analysis were more likely to breastfeed longer, not introduce solid foods before 4 months, be white, have higher income, be married, be multiparous, have at least a college degree, and have lower prepregnancy BMI, compared to those excluded from the analysis.

We calculated prevalence of obesity at 6 years by maternal and infant characteristics and used a chi-square test to assess group differences. We used unadjusted and multivariable logistic regression to assess whether timing of introduction of solid foods was associated with obesity at 6 years and test for an interaction to see whether the association between early solid food introduction and subsequent obesity varied by breastfeeding status. We first adjusted for maternal characteristics, including maternal age, race, education, PIR, prepregnancy BMI, marital status, and parity, and infant characteristics, including sex, birth weight, and gestational age. In a third model, we adjusted for the previously mentioned covariates as well as child characteristics, including daily consumption of water, fruits, vegetables, and SSBs. For timing of solid introduction, we used a chi-square test to assess group differences. All analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Overall prevalence of obesity in our sample at 6 years was 12.0% (Table 1) and varied by maternal race/ethnicity, education, PIR, prepregnancy BMI, marital status, and infant’s birth weight.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Obesity at 6 Years by Maternal and Infant Characteristics

| N (%) | % obese | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Total | 1181 (100.0) | 12.0 | |

| Maternal characteristicsa | |||

| Maternal age (y) | 0.2 | ||

| 18–25 | 152 (12.9) | 17.8 | |

| 25–29 | 390 (33.0) | 10.8 | |

| 30–35 | 390 (33.0) | 12.3 | |

| ≥35 | 249 (21.1) | 12.5 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.003 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1043 (88.3) | 12.1 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 35 (3.0) | 28.6 | |

| Hispanic | 59 (5.0) | 18.6 | |

| Other | 44 (3.7) | 2.3 | |

| Education | <0.0001 | ||

| ≤High school | 179 (15.2) | 24.0 | |

| 1–3 y college | 425 (36.0) | 13.7 | |

| ≥College | 577 (48.9) | 8.2 | |

| Poverty-income ratio (%) | 0.003 | ||

| <185 | 397 (33.6) | 17.4 | |

| 185–349 | 449 (38.0) | 10.2 | |

| ≥350 | 335 (28.4) | 9.9 | |

| Prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | <0.0001 | ||

| <18.5 | 44 (3.7) | 11.4 | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 541 (45.8) | 6.8 | |

| 25.0–29.9 | 297 (25.2) | 16.5 | |

| ≥30.0 | 299 (25.3) | 19.1 | |

| Marital status | <0.0001 | ||

| Married | 1001 (84.8) | 10.9 | |

| Not married | 180 (15.2) | 22.7 | |

| Parity | 0.6 | ||

| Primiparous | 317 (26.8) | 11.0 | |

| Multiparous | 864 (73.2) | 13.1 | |

| Child characteristics | |||

| Sex | 1.0 | ||

| Girl | 592 (50.1) | 12.5 | |

| Boy | 589 (49.0) | 12.6 | |

| Birth weight (g) | 0.0004 | ||

| <4000 | 1029 (87.1) | 11.6 | |

| ≥4000 | 152 (12.9) | 19.1 | |

| Gestational age (wk) | 0.9 | ||

| <37 | 48 (4.1) | 14.6 | |

| ≥37 | 1133 (95.9) | 12.4 | |

Maternal characteristics are from the baseline Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPS II) survey.

p values are from chi-square tests.

y, years; wk, weeks.

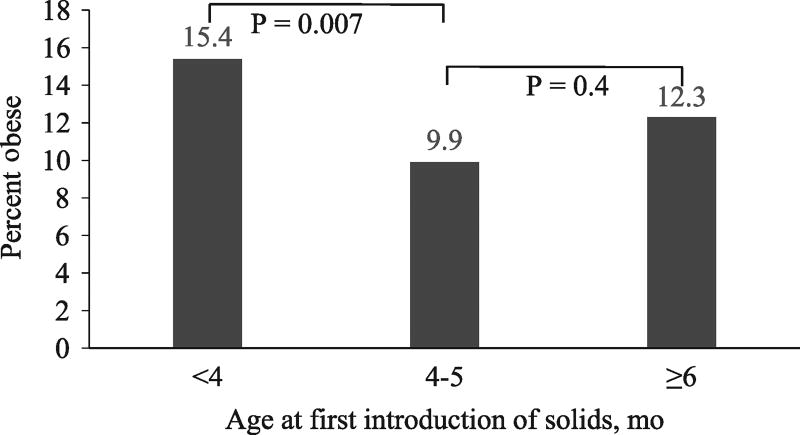

The relationship between timing of introduction of solid foods and obesity at 6 years differed significantly between those introduced before 4 months and those introduced at 4–<6 months (15.4% vs. 9.9%; p = 0.007), but not between those introduced at 4–<6 months and those introduced at 6 months or older (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Association between timing of solid food introduction during infancy and obesity at 6 years of age (BMI ≥95th percentile; n = 1181). P values are from unadjusted logistic regression. mo, months.

Odds of obesity at 6 years, by timing of introduction of solid foods during infancy, is shown in Table 2. Compared to infants who first received solid foods at 4–<6 months of age, infants introduced to solids before 4 months had increased odds of obesity at 6 years (odds ratio [OR] = 1.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.15, 2.40) in unadjusted analysis; however, this association was no longer present after adjusting for covariates (OR = 1.18; 95% CI, 0.79, 1.77). Compared to infants introduced to solid foods at 4–<6 months, those introduced to solid foods at 6 months or older did not have different odds of obesity in the unadjusted or adjusted analysis. In the full model, interaction between timing of introduction of solid foods and breastfeeding duration was not significant (p = 0.2); as such, we did not included it in subsequent analyses.

Table 2.

Odds of Obesity (BMI ≥95th Percentile) at 6 Years According to Timing of Introduction of Solid Foods During Infancy

| Age, mo | N | Model 1a (OR) | Model 2b (aOR) | Model 3c (aOR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| <4 | 512 | 1.66 (1.15–2.40) | 1.18 (0.79–1.76) | 1.18 (0.79–1.77) |

| 4–<6 | 555 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| ≥6 | 114 | 1.27 (0.68–2.38) | 1.23 (0.64–2.37) | 1.23 (0.64–2.38) |

Model 1: unadjusted odds ratio.

Model 2: adjusted for baseline maternal characteristics (age, education, race/ethnicity, PIR, marital status, parity, and prepregnancy BMI) and infant characteristics (sex, birth weight, and gestational age).

Model 3: adjusted for baseline maternal characteristics (age, education, race/ethnicity, PIR, marital status, parity, and prepregnancy BMI), infant characteristics (sex, birth weight, and gestational age), and child characteristics (daily consumption of water, fruits, vegetables, and sugar-sweetened beverages).

mo, months; OR, odds ratio; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; PIR, poverty-income ratio.

Discussion

Findings regarding the association between timing of introduction of solid foods and subsequent obesity have been inconsistent, with some evidence suggesting that the association between timing of solid food introduction and subsequent obesity may differ for breastfed and formula-fed infants.11 One explanation for why studies may have found an association between timing of introduction of solids and subsequent obesity among formula-fed, but not breastfed, infants is that infants fed at the breast are better able to self-regulate their intake in response to solid foods being added to their diet by decreasing their consumption of human milk.16 In contrast, solid foods given to formula-fed infants may be additive, rather than substitutive, potentially because infants fed from a bottle are more dependent on the caregiver’s input, which is likely influenced by external cues, such as feeding until the bottle is empty.17

Despite this possible mechanism, in our sample, we did not find an interaction between breastfeeding status and timing of solid food introduction and subsequent obesity, nor did we find an association between timing of solid food introduction and subsequent obesity when breastfeeding status was not taken into account.

Findings of an association between early introduction to solids and childhood obesity are difficult to determine, given that when solid foods are introduced is inextricably linked to exclusive breastfeeding duration and formula feeding; therefore, residual confounding cannot be ruled out.11 Inconsistent with our findings, Huh and colleagues found a 6-fold increase in odds of obesity at 3 years among those breastfed less than 4 months and introduced to solids before 4 months, but not among those breastfed longer.12 The differences found among studies regarding the influence of breastfeeding status on timing and subsequent obesity may be linked to variations in study design, categorizations of infant feeding, and definitions of terms such as “starting solids.”11

Limitations of our study include that the sample population is not nationally representative. Additionally, child obesity at 6 years of age was based on measurements of height and weight taken by the mother, which may be susceptible to measurement error. In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2012, which assesses measured height and weight, prevalence of obesity was 8.4% among 2- to 5-year-olds and 17.7% among 6- to 11-year-olds, which is generally consistent with our estimate. The major strength of this analysis was the ability to control for many sociodemographic and dietary factors that have often not been controlled for in other studies. Additionally, information on timing of introduction of solid foods and breastfeeding duration were calculated from approximately monthly recalls assessed throughout infancy, limiting recall bias that may occur when asking about these practices when the child is older.

Conclusions

In this study, we did not find a significant association between timing of introduction of solid foods and child obesity at 6 years of age. Despite our findings, optimal infant feeding practices, including exclusive breastfeeding for approximately the first 6 months, timely introduction of complementary foods, and continued breastfeeding for at least the first year,18 should be promoted and supported for all infants because of the numerous health benefits for infants and mothers.19–21

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. NCHS Data Brief no. 219. National Center for Health Statistics; Atlanta, GA: Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reilly JJ, Methven E, McDowell ZC, et al. Health consequences of obesity. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:748–752. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.9.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity. Solving the problem of childhood obesity within a generation. [Last accessed March 17, 2016];2010 doi: 10.1089/bfm.2010.9980. Available at www.letsmove.gov/white-house-task-force-childhood-obesity-report-president. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Gillman MW. Early infancy as a critical period for development of obesity and related conditions. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program. 2010;65:13–20. doi: 10.1159/000281141. discussion, 14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clayton HB, Li R, Perrine CG, et al. Prevalence and reasons for introducing infants early to solid foods: Variations by milk feeding type. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1108–e1114. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatric Nutrition Handbook. 6. American Academy of Pediatrics; Elk Grove Village, IL: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Infant nutrition and feeding: A guide for use in the WIC and CSF programs. United States Department of Agriculture; Washington, DC: 2009. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women Infants and Children (WIC), Food and Nutrition Service. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence RA, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115:496–506. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatric Nutrition. 7. American Academy of Pediatrics; Elk Grove Village, IL: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization (WHO) Complementary feeding. [Last accessed October 20, 2015]; Available at www.who.int/nutrition/topics/complementary_feeding/en.

- 11.Daniels L, Mallan KM, Fildes A, et al. The timing of solid introduction in an ‘obesogenic’ environment: A narrative review of the evidence and methodological issues. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2015;39:366–373. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huh SY, Rifas-Shiman SL, Taveras EM, et al. Timing of solid food introduction and risk of obesity in preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e544–e551. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fein SB, Li R, Chen J, et al. Methods for the Year Six Follow Up Study of children who participated in Infant Feeding Practices Study II. [Last accessed March 17, 2016];Pediatrics. 2014 134(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0646C. Available at http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/134/Supplement_1/S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC growth charts. [Last accessed July 11, 2013]; Available at www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/cdc_charts.htm.

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cut-offs to define outliers in the 2000 CDC growth charts. [Last accessed July 10, 2013]; Available at www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/growthcharts/resources/BIV-cutoffs.pdf.

- 16.Young BE, Krebs NF. Complementary feeding: Critical considerations to optimize growth, nutrition, and feeding behavior. Curr Pediatr Rep. 2013;1:247–256. doi: 10.1007/s40124-013-0030-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li R, Magadia J, Fein SB, Grummer-Strawn LM. Risk of bottle-feeding for rapid weight gain during the first year of life. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:431–436. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eidelman AI, Schanler RJ, Johnston M, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129:E827–E841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2007. AHRQ publication no. 07-E007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauck FR, Thompson JM, Tanabe KO, et al. Breastfeeding and reduced risk of sudden infant death syndrome: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2011;128:103–110. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarz EB, Ray RM, Stuebe AM, et al. Duration of lactation and risk factors for maternal cardiovascular disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:974–982. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000346884.67796.ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]