Abstract

Olfactory neuroblastoma (ONB) is a rare malignant neoplasm of the sinonasal tract that arises from olfactory epithelium. There have been reports, mainly in tumors treated with chemoradiation or with distant metastases, describing focal histologic changes of divergent cell populations within archetypal ONB. Only three cases have been reported of ONB coexisting with non-neuroendocrine tumors. We describe our experience with a 35-year-old male with a nasal cavity mass extending into the anterior cranial fossa. Pathology revealed this to be a high grade malignant neoplasm with features of olfactory neuroblastoma and a significant divergent population of pancytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen-reactive cells. The patient underwent combined endoscopic and open craniofacial resection followed by adjuvant chemoradiation. We describe the clinical presentation, treatment, and outcome followed by a review of the literature. Surgical pathology clearly demonstrated two cell populations evenly distributed and displaying classic histologic and immunohistochemical markers of ONB, as well as poorly differentiated cells with an epithelial immunophenotype. The patient is now 16 months status post completion of treatment with no evidence of recurrence. Our patient’s presentation is unique and unusual in that the tumor demonstrated a high grade olfactory neuroblastoma and a divergent, epithelial-marker reactive cell population in the same tumor. This combined appearance is unusual and may represent an “olfactory carcinoma”. Only one previous case has reported carcinomatous involvement of an ONB. There is insufficient information in the literature to draw conclusions on the impact these divergent cell populations have on prognosis or treatment.

Keywords: Olfactory carcinoma, Esthesioneuroblastoma, Round blue cell tumor, Nasal cavity tumor

Introduction

Olfactory neuroblastoma (ONB), also commonly known as esthesioneuroblastoma, is a rare malignant neoplasm that accounts for 2–3% of nasal cavity malignancies. It arises from the neural–epithelial olfactory mucosa of the cribriform plate. While typically locally invasive, cervical metastases are not uncommon on presentation, and distant disease can surface many years after initial diagnosis [1–3]. Early detection is key for effective treatment of this rare malignancy, but it is frequently delayed due to non-specific clinical findings, the inaccessible area of growth, and the significant overlap in histologic characteristics with other sinonasal neuroendocrine tumors [2, 4]. When confined to the nasal cavity, 5-year survival rates have been reported as high as 75%, but when extending beyond the nasal cavity, either by direct spread or metastasis, those rates fall to 41% [3]. There have been reports describing focal histologic changes of divergent cell populations with distinct characteristics within archetypal ONB, but mainly in tumors with distant metastases or those that have undergone chemoradiation. We describe a unique case of a high grade malignant neoplasm with features of both olfactory neuroblastoma and a divergent, immunophenotypically epithelial population.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old male was referred to the Otolaryngology clinic for evaluation of a several month history of right-sided nasal congestion, intermittent epistaxis, headaches, and hyposmia. He denied diplopia, vision changes, facial hypoesthesia, tobacco use, and unusual occupational exposures. Surgical history was pertinent for a correction of a deviated nasal septum and nasal turbinate reduction several years before for nasal dyspnea, with only temporary relief of symptoms. No comorbid conditions were elicited on medical history. Physical exam with rigid nasal endoscopy revealed a large polypoid mass in the right nasal cavity located between the nasal septum and a lateralized middle turbinate obscuring the olfactory cleft (Fig. 1). The remainder of the head and neck exam was unremarkable with no cervical lymphadenopathy appreciated. The cranial nerves were intact. A biopsy of the mass was obtained in clinic under endoscopic visualization.

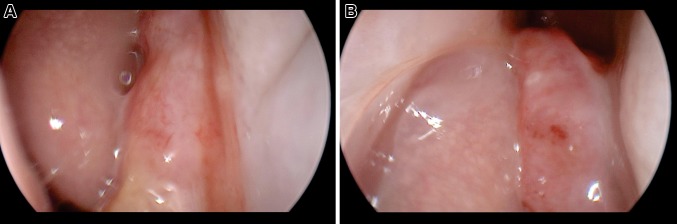

Fig. 1.

Tumor lodged between middle turbinate and septum at level of right middle meatus (left). Tumor originating from right olfactory cleft above level of middle turbinate root (right)

Given the suspicious appearance and location of the mass, imaging was then acquired with computed tomography (CT) which identified a soft tissue mass in the superior right nasal cavity extending and eroding through the cribriform plate as well as into the left nasal cavity. Further characterization was achieved with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) which confirmed a 4 × 3 × 1 cm mass that was hyperintense on T1 with intracranial space extension and obstruction of the right frontal sinus outflow tract but no erosion of the medial orbital wall (Fig. 2). The clinic biopsy specimen demonstrated a high grade malignant neoplasm with features of olfactory neuroblastoma and poorly differentiated carcinoma. The patient was offered surgical excision and underwent an en-bloc resection through a combined endonasal endoscopic and open craniofacial approach with the assistance of the Neurosurgery service. Negative margins were obtained intraoperatively. A pericranial flap and a split calvarial bone graft were used to reconstruct the anterior cranial fossa floor defect.

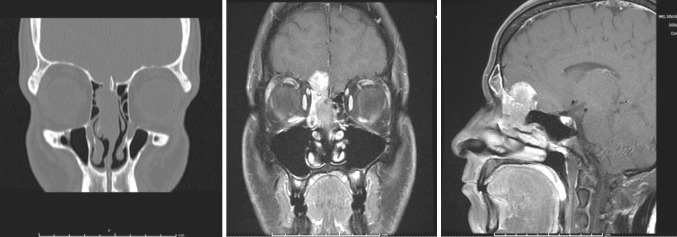

Fig. 2.

Coronal CT demonstrating tumor extending into cribriform plate and lateral lamella (left). Coronal and sagittal T1 MRI cuts with gadolinium and fat saturation demonstrating enhancement of lesion with intracranial extension (middle and right)

Diagnosis

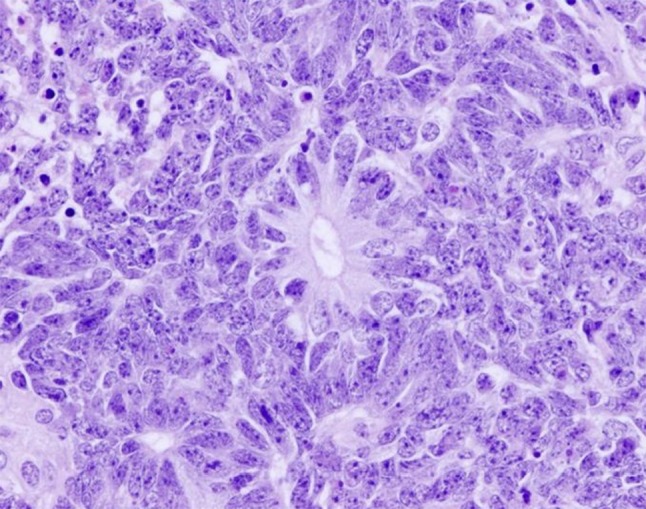

The main tumor specimen demonstrated a distinct biphasic population of malignant tumor cells. The majority of the lesion demonstated small, round blue cells within a neurofibrillary matrix. These cells were in small nests, clusters or individually scattered. Focal true rosettes (Flexner–Wintersteiner) and pseudorosettes (Homer Wright) were present (Fig. 3). Necrosis was focally prominent. These cells reacted strongly with neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin, neuron specific enolase and CD56, while weakly with chromogranin. Focal islands of cells were surrounded by an S100-reactive sustentactular network. These features, in addition to the anatomic location were in keeping with olfactory neuroblastoma. A second population of small, elliptical-to-round epithelioid cells was also evident. These cells composed variably sized nests and ribbons and displayed a much higher mitotic index, to include atypical forms. Rosette formation was not evident in this population. Interestingly, these cells were non-reactive with neuroendocrine markers, yet were highlighted by pancytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). Additionally, the overlying mucosa demonstrated changes similar in character to severe epithelial dysplasia or carcinoma-in-situ. The immunohistochemical profile resulted in a unique, two-population appearance, with the epithelial-reactive islands being surrounded by neuroendocrine-reactive cells and matrix (Fig. 4). This overall unusual presentation of an olfactory neuroblastoma intertwined with a non-neuroendocrine, cytokeratin and EMA-reactive population may be indicative of an “olfactory carcinoma”.

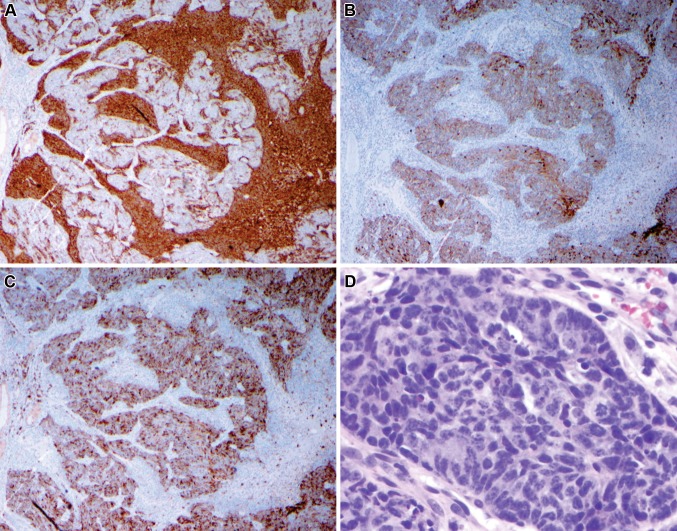

Fig. 3.

High power view demonstrates “Flexner–Wintersteiner” rosette with numerous lesional cells in a circular duct-like arrangement. Scattered mitotic figures are also seen

Fig. 4.

Two separate populations of cells are evident under immunohistochemistry. Low power: synaptophysin (a) strongly stains the more loosely cohesive cell population. These cells were also strongly positive for CD56. Pan-cytokeratin (b) and epithelial membrane antigen (c) distinctly highlight the solid component. Note when comparing the three images that separate cellular regions are highlighted, with the neuroendocrine population surrounding the epithelial marker-reactive cells. The epithelial-reactive solid component (d—high power) is composed of small cells with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and high mitotic activity

Discussion

The differential diagnosis of malignant tumors of the nasal cavity mass can be extensive. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common, representing 55% of sinonasal malignancies followed by nonepithelial neoplasms [1]. Less common malignancies include but are not limited to adenocarcinoma, olfactory neuroblastoma (esthesioneuroblastoma), sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma (SNUC), extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and mucosal melanoma [2, 4].

Olfactory neuroblastoma belongs to the class of primary sinonasal neuroendocrine tumors of which there are four recognized histologic phenotypes: olfactory neuroblastoma, sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma (SNUC), sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma (SNEC) and small cell undifferentiated carcinoma (SmCC) [4]. These uncommon tumors differ in cell of origin, extent of differentiation, and biologic behavior. Olfactory neuroblastoma represents the most differentiated and SmCC the least, but there is significant overlap in their presentations [4].

Histologically, olfactory neuroblastoma typically appears as a submucosal lesion with a prominent nested cell structure separated by hyalinized fibrous stroma [2]. The cells are classically small and round with a salt and pepper chromatin and minimal cytoplasm, mimicking other small, round cell tumors [1]. However, they may also appear similar to carcinoid tumors with small nuclei and eosinophilic or amorphilic cytoplasm [2]. The nests of cells are encircled by richly vascularized and hyalinized matrix, though this too can vary, appearing rather with inflammatory, non-necrotizing granulomatous or even normal tissue characteristics [2, 3]. Lesional tissue may contain “Homer Wright” pseudorosettes and less commonly true neural “Flexner–Wintersteiner” rosettes, with the former being nearly pathognomonic in the nasal cavity for olfactory neuroblastoma when containing true neurofibrillary matrix [2, 3].

Immunohistochemically, olfactory neuroblastoma typically demonstrates strong positive staining for neuroendocrine and neural markers including neuron-specific enolase, synaptophysin, chromogranin, CD56, CD57 and calretinin [2, 3, 5]. The sustentacular matrix also stains positive to S100, though this can be lost in high-grade tumors [3, 5]. Keratins and epithelial membrane antigen may highlight only isolated cells. Desmin, myogenin, leukocyte common antigen (CD45RB) and CD99 are typically negative and there is rarely more than focal staining for p63 [2, 5]. While there is significant variability in this staining pattern, and there is no single immunostain that can unequivocally make the diagnosis of olfactory neuroblastoma, the combination of strong staining with either synaptophysin or chromogranin and moderate-to-strong staining with calretinin, in addition to a negative staining for p63 can effectively rule out the major alternative diagnosis and therefore support a diagnosis of olfactory neuroblastoma [2, 3, 5].

Rare cases of olfactory neuroblastoma have shown divergent differentiation with focal populations of cells showing distinct characteristics, including melanocytic, myogenic, neural or epithelial [2]. However, these changes have been described as being focal effects within portions of the otherwise typical olfactory neuroblastoma, and may only be present following chemoradiation or in distant metastases where the differentiated cell types are similar to the local tissue [2]. In addition, there are three reported cases of a neuroblastoma existing with non-neuroendocrine tumors mixed-in throughout the otherwise typical tumor [6, 7]. Only one of these cases described carcinomatous involvement, but as it was described in 1984, the analysis lacked many of the immunohistochemical markers relied on today to distinguish olfactory neuroblastoma from similar sinonasal tumors [6].

The surgical pathology of the case presented here is unique in that it displayed many of the classic histologic and immunohistochemical markers of olfactory neuroblastoma, while it also displayed a second population of cytokeratin and EMA-reactive nests and islands of cells throughout the tumor. Although olfactory neuroblastoma can occasionally demonstrate keratin-reactive cells, these are typically focal and rare. In addition, the tumor islands in a typical ONB display a neuroendocrine phenotype. This case is unusual in that a much higher population than normal is reactive for epithelial markers, and these same nests and islands are negative for neuroendocrine IHC’s.

The location of the tumor in the superior nasal cavity with extension into the intracranial space, histologic pattern of a small-blue cell appearance with presence of true rosettes, and neuroendocrine immunohistochemical pattern with S100-reactive sustentactular cells all strongly support a diagnosis of olfactory neuroblastoma [2, 3, 5]. However, the islands and ribbons of malignant pancytokeratin/EMA-reactive epithelioid cells suggest a divergent population, and may be indicative of carcinomatous change within an olfactory neuroblastoma.

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for olfactory neuroblastoma with anterior craniofacial resection plus or minus an endonasal endoscopic approach [1, 2]. Resection by means of endoscopic surgery alone is gaining traction with several studies and one meta-analysis showing comparable results to open surgery when used in less invasive tumors [8]. Adjuvant and/or neoadjuvant radiation therapy has been shown to offer better local control (86 vs. 17% with surgery alone), particularly when negative margins are difficult to obtain due to proximity to vital structures [1, 2, 9]. Unfortunately, due to the location, indolent nature of the disease, and non-specific symptoms, olfactory neuroblastoma is frequently not found until it has progressed and invaded surrounding structures [2]. Five to eight percent of patients present with local metastases to cervical lymph nodes, lowering the 5 year survival rate to 29% compared with 64% in patients with no cervical adenopathy [1, 10]. Furthermore, 18–25% of patients without metastases at presentation will go on to develop cervical nodal metastases, leading some to recommend elective neck irradiation to limit this spread [1, 9]. Recurrence has been reported to occur in 40–46% of patients, with a mean time of 2 years and only 2 reported cases of recurrences at greater than 10 years [1, 2, 9].

Following postoperative recovery, our patient underwent adjuvant treatment with proton beam radiation and has no clinical or radiologic evidence of recurrence 1 year following completion of therapy.

Conclusion

Olfactory neuroblastoma is an uncommon tumor of the nasal cavity that may very rarely divergently differentiate thus presenting a diagnostic challenge. The case reported here is unique and unusual in that the tumor demonstrated a high grade olfactory neuroblastoma and a divergent, immunophenotypically epithelial cell population in the same tumor mass. This combined appearance is rare and may be in keeping with an “olfactory carcinoma”. There is insufficient information available to draw conclusions on the impact these divergent cell populations may have on prognosis or treatment. Further research is needed to fully understand the mechanism of these changes and their impact on management.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense or the United States Government. I am a military service member. This work was prepared as part of my official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that ‘Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.’ Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a United States Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the United States Government as part of that person’s official duties.

Funding

There was no funding involved with this project.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors of this paper have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Poster Presentation: American Rhinologic Society, Combined Otolaryngology Spring Meetings, Chicago IL, May 2016.

References

- 1.Su SY, Bell D, Hanna EY. Esthesioneuroblastoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, and sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma: differentiation in diagnosis and treatment. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;18(Suppl 2):S149–S156. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faragalla H, Weinreb I. Olfactory neuroblastoma: a review and update. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16(5):322–331. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181b544cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wooff JC, Weinreb I, Perez-Ordonez B, Magee JF, Bullock MJ. Calretinin staining facilitates differentiation of olfactory neuroblastoma from other small round blue cell tumors in the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(12):1786–1793. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182363b78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menon S, Pai P, Sengar M, Aggarwal JP, Kane SV. Sinonasal malignancies with neuroendocrine differentiation: case series and review of literature. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53(1):28–34. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.59179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson LD. Olfactory neuroblastoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3(3):252–259. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0125-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller DC, Goodman ML, Pilch BZ, et al. Mixed olfactory neuroblastoma and carcinoma. A report of two cases. Cancer. 1984;54(9):2019–2028. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841101)54:9<2019::AID-CNCR2820540940>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang KC, Jin YT, Chen RM, Su LJ. Mixed olfactory neuroblastoma and craniopharyngioma: an unusual pathological finding. Histopathology. 1997;30(4):378–382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.d01-615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devaiah AK, Andreoli MT. Treatment of esthesioneuroblastoma: a 16-year meta-analysis of 361 patients. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(7):1412–1416. doi: 10.1002/lary.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz EM, Jr, Johnigan RH, 3rd, Pero C, et al. Olfactory neuroblastoma: the 22-year experience at one comprehensive cancer center. Head Neck. 2005;27(2):138–149. doi: 10.1002/hed.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dulguerov P, Allal AS, Calcaterra TC. Esthesioneuroblastoma: a meta-analysis and review. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2(11):683–690. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00558-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]