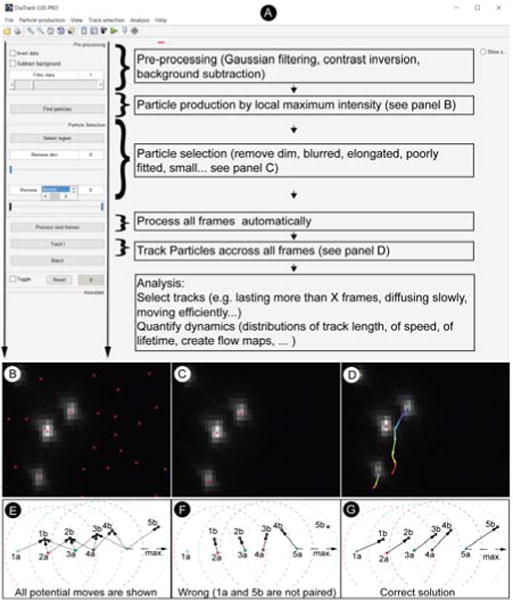

Figure 1.

A) The workflow in Diatrack guides the user naturally, from particle production (see panel B) and particle selection (see panel C), down to track production (see panel D), selection, and analysis. B) Immediately after particle production, a large number of particles do not correspond to genuine objects. C) Spurious particles must be systematically eliminated using a combination of selection tools such as the “remove blurred” slider, until only genuine particles are retained. D) The ability to identify and track spots with high precision even when they are in close proximity to each other is illustrated. A particle is seen passing near another one less than 3 pixels away. High precision tracking allows reporting on molecular events at the single-molecule level. E) Illustration of the notion of assignment conflict. In order to construct trajectories, particles 1a, 2a, 3a, 4a and 5a observed in time frame marked by “a” must be associated with particles seen at positions 1b, 2b, 3b, 4b and 5b one frame later. Given the maximum jump amplitude shown by dashed circles, all possible particle motions are indicated by dashed arrows. Particles compete with each other for assignment. F) In order to form tracks, one might first want to assign particle 3a with particle 2b because they lie in closest proximity. However, proceeding in order of proximity will eventually leave particle 1a and 5b unpaired (the suboptimal solution is shown). G) Using Diatrack’s graph-based algorithm a solution that maximizes the pairing of particles may be found. Note that when particles are quite likely to disappear (e.g. in the presence of out of focus motion), the “suboptimal” solution shown in F) should probably be preferred over the “optimal solution” because the latter imposes a much greater total overall particle displacement. The best algorithm must strike a delicate balance between maximal matching of particles between frames and the ability to deal gracefully with particle appearance and disappearances (see Figure 2).