Abstract

Banded iron formations (BIFs) in Archean cratons provide important “geologic barcodes” for the global correlation of Precambrian sedimentary records. Here we report the first finding of late Archean BIFs from the Yangtze Craton, one of largest Precambrian blocks in East Asia with an evolutionary history of over 3.3 Ga. The Yingshan iron deposit at the northeastern margin of the Yangtze Craton, displays typical features of BIF, including: (i) alternating Si-rich and Fe-rich bands at sub-mm to meter scales; (ii) high SiO2 + Fe2O3total contents (average 90.6 wt.%) and Fe/Ti ratios (average 489); (iii) relative enrichment of heavy rare earth elements and positive Eu anomalies (average 1.42); (iv) and sedimentary Fe isotope compositions (δ56FeIRMM-014 as low as −0.36‰). The depositional age of the BIF is constrained at ~2464 ± 24 Ma based on U-Pb dating of zircon grains from a migmatite sample of a volcanic protolith that conformably overlied the Yingshan BIF. The BIF was intruded by Neoproterozoic (805.9 ± 4.7 Ma) granitoids that are unique in the Yangtze Craton but absent in the North China Craton to the north. The discovery of the Yingshan BIF provides new constraints for the tectonic evolution of the Yangtze Craton and has important implications in the reconstruction of Pre-Nuna/Columbia supercontinent configurations.

Introduction

The Archean-Paleoproterozoic boundary was a critical period in Earth’s history with a series of significant changes in atmosphere, lithosphere and hydrosphere1,2. The formation of BIFs also reached its climax during this period3. The BIFs worldwide are important repositories of the early Earth’s major environmental transitions and biological innovations2–4. They are considered to have formed in distinct tectonic settings. For example, the Superior-type BIFs are thought to have developed on continental shelf below storm wave base, and granular iron-formations such as the Gunflint-type BIFs developed in shallow-water, high-energy environments3. In contrast, the Neoproterozoic iron formations are commonly associated with continental rift-basins5. Records of BIFs therefore provide important constraints on the tectonic histories of Earth’s ancient crustal blocks. The Yangtze Craton (Fig. 1a) in South China is one of the largest Precambrian blocks in East Asia, with an Archean-Paleoproterozoic basement6,7 that dates back to 3.3 Ga8,9. Although a number of Neoproterozoic iron formations occur around the southeastern margin of the Yangtze Craton (Fig. 1a), so far there has been no report on Archean-Paleoproterozoic BIFs from this craton10,11, which is in sharp contrast with the North China Craton to the north where Archean-Paleoproterozoic BIFs are abundant11,12.

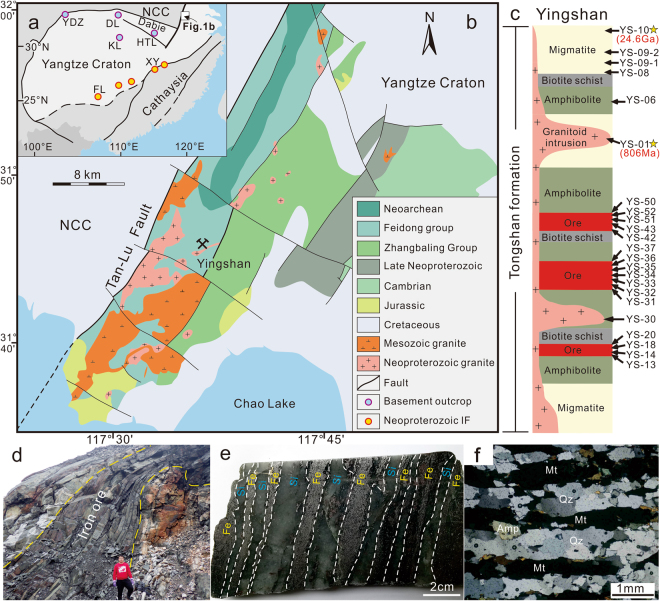

Figure 1.

Location (a) and geological map (b) of the Yingshan iron deposit. Stratigraphic column of the Yingshan iron deposit (c) showing sampling point (arrow) and zircon U-Pb age (star). Representative photos showing macroband (d), mesoband (e), and microband (f) textures of the iron ores from Yingshan, that are similar to those of typical BIF bands elsewhere in the world such as the Dales Gorge Member, Hamersley basin. Acronyms in Fig. 1a: NCC-North China Craton; YDZ-Yudongzi group; DL-Douling complex; KL-Kongling complex; HTL-Huangtuling granulites; XY-Xinyu iron formation (Neoproterozoic); FL-Fulu iron formation (Neoproterozoic). The geological maps were generated using CorelDRAW Graphcs Suite 2017, http://www.coreldraw.com/cn/free-trials/?topNav=cn.

Whether the absence of BIFs in the Yangtze Craton is a preservational issue or it reflects the lack of a favorable tectonic environment for Archean-Paleoproterozoic BIF deposition is a crucial question, particularly in understanding the evolution of this craton and its position with respect to pre-Nuna/Columbia supercontinents13. Occurrence of magnetite quartzite has been mentioned from the Archean-Paleoproterozoic Feidong Group14 and the Archean Yudongzi group15 around the boundary between the North China Craton and the Yangtze Craton (Fig. 1a), but their protolith, age and tectonic affinity remain elusive. In this contribution, we place geochronological and geochemical constraints on the magnetite quartzite from the Paleoproterozoic Feidong Group16,17. Our data provide unequivocal evidence for ca. 2.46 Ga BIFs from the Yangtze Craton, confirming the first discovery of late Archean BIFs in this craton.

Geological setting, samples, and analyses

The Yangtze Craton, separated from the North China Craton by the Qinling-Sulu-Dabie orogen to the north, contains a widespread Archean basement6,7. Much of the basement is covered by weakly metamorphosed Neoproterozoic (eg., Lengjiaxi group and Banxi group) and Phanerozoic strata, with limited Archean-Paleoproterozoic outcrops restricted to the northern part of the craton (e.g., Kongling complex >3.3 Ga; Fig. 1a)6–8.

The Tan-Lu fault, the largest fault system in East Asia, defines the eastern boundary between the North China Craton and the Yangtze Craton (Fig. 1a,b). The fault sinistrally offsets the Sulu-Dabie orogen by a maximum apparent displacement of ~400 km, exposing a NEE-trending belt of the basement of the Yangtze Craton, locally termed as the Zhangbaling metamorphic belt17,18. This belt is composed of the greenschist-facies Neoproterozoic Zhangbaling Group in the north and the amphibolite-facies Paleoproterozoic Feidong Group in the south17. The Feidong Group contains the Fuchashan, the Tongshan and the Qiaotouji formations from bottom to top. The Tongshan Formation is a metamorphosed sedimentary-volcanic succession and contains several thin-bedded magnetite quartzite layers that extend over 30 km (Fig. 1c).

The Yingshan iron deposit is hosted in the Tongshan Formation of the Feidong Group. The ore bodies occur as Fe-rich layers that typically extend for over 1 km with an average thickness of over 10 m and Fe grade of 27 wt.% (Supplementary Fig. S1). The ores consist of banded quartz-magnetite and garnet-amphibolite-quartz-magnetite (Supplementary Fig. S1). The layered ore bodies are inter-bedded with amphibolite, biotite schist and migmatite, and have been intruded by granitoids (Supplementary Fig. S1). The rocks locally underwent amphibolite-grade metamorphism, structural deformation and hydrothermal alteration associated with the Tan-Lu fault system (Supplementary Fig. S1) during the Triassic17.

Twenty-six samples were collected from the Yingshan deposit (Fig. 1c), including iron ores from three layers of orebodies, as well as the host rocks including migmatite, biotite schist and amphibolites. Bulk rocks were pulverized and analyzed for major and trace elements using XRF and ICP-MS, respectively. Iron isotope compositions of the bulk rocks were measured by solution-nebulization MC-ICP-MS after ion-exchange purification. Zircon grains were separated from a leucosome (YS-10) sample from the upper wall of the ore bodies, and a granitoid (YS-01) that intruded into the iron ore bodies (Fig. 1c). The grains were analyzed using LA-ICP-MS for U-Pb dating. Details of the results are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Results and Discussion

Protolith of the iron ores

In spite of the deformation and metamorphism, the iron ores from Yingshan show characteristic banded texture with alternating silica-rich and iron-rich layers. The banded textures are obvious in meter scale within the layered ore bodies (Fig. 1d), at centimeter scale in hand specimens (Fig. 1e), and at sub-millimeter scale within iron-rich bands under the microscope (Fig. 1f). These are consistent with the classic macroband, mesoband, and microband textures of typical BIFs as for example in the case of the Dales Gorge Member in the Archean-Proterozoic Hamersley basin, western Australia19.

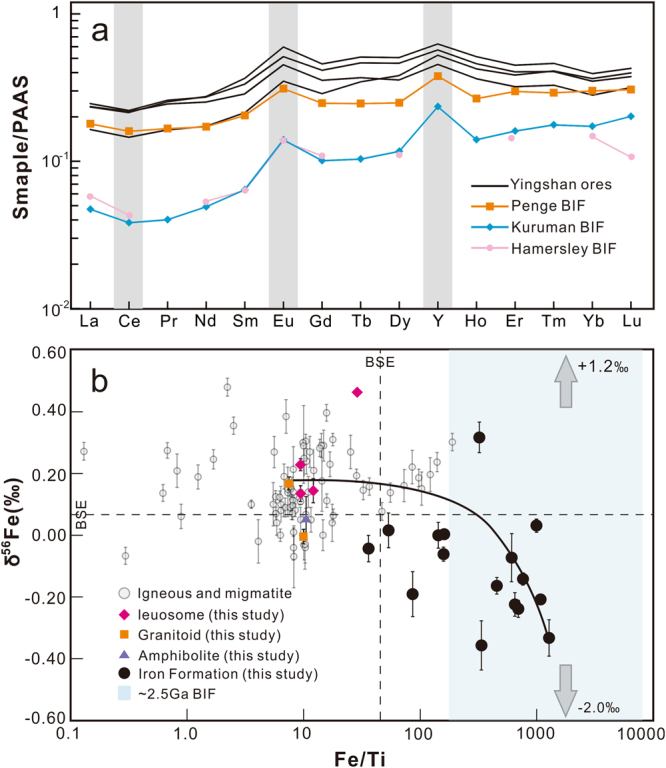

Major elements of the banded iron ores (Supplementary Table S1) are dominated by SiO2 and Fe2O3Total (79.4–95.8 wt%), a feature characteristic for oceanic chemical deposits, and consistent with the average composition of BIFs as summarized from 214 BIFs worldwide3. The variable contents of Al2O3 (1.66–9.81 wt%) and TiO2 (0.04–0.86 wt%) likely reflect syndepositional volcanic inputs. Additionally, ore samples with low Al2O3 and TiO2 contents display rare earth element plus Y (REE + Y) patterns of relative enrichment in heavy REE (average HREE/LREE* = 2.28) and positive Eu anomalies (average = 1.42) (Supplementary Table S4). The REE + Y patterns of the iron ores are similar to those of the classic BIFs formed during the Archean-Proterozoic transition (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

Plots of rare earth element plus yttrium (REE + Y) patterns (a), and δ56Fe (‰ relative to IRMM-014) versus Fe/Ti ratios (b) for samples from the Yingshan iron deposit. For comparison, the REE + Y patterns of ~2.5 Ga Hamersley, Penge and Kuruman BIF are also plotted in Fig. 2a. Data of igneous rocks (Supplementary Table S2) and banded iron formations (Supplementary Table S3) are plotted as light gray dots and light yellow shaded rectangles, respectively. The solid curve denotes the mixing trend between YS-01 (granitoid) and YS-43 (banded ore).

Iron isotope analyses for all the 23 samples (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table S1) revealed a variation of 0.83‰ in δ56Fe. The wall-rock samples, including leucosome of migmatite, amphibolite and granitoid intrusion, have positive δ56Fe values (0.00–0.47‰). In contrast, ore samples are generally enriched in light Fe isotopes, with δ56Fe ranging from −0.36‰ to 0.04‰ with an exception of one sample that has δ56Fe of +0.32‰ (Fig. 2b). Magmatic rocks in general possess a homogeneous Fe isotope composition20,21, except for highly evolved (SiO2 > 70 wt%) granitoids and leucosome of migmatites that have high δ56Fe values22,23. The variable and low δ56Fe values of the iron ores therefore exclude an igneous parentage, and instead reflect Fe isotope variation in the protolith. The complexities in bulk rock Fe isotope compositions caused by mixing with detrital components as well as metamorphism and hydrothermal alteration can be assessed using a plot of δ56Fe versus Fe/Ti. This approach has proven to be effective in resolving the protolith of the earliest BIF from the highly metamorphosed 3.8 billion-year-old rocks of Isua, Greenland24 (Fig. 2b). There is a general negative correlation between the Fe/Ti atomic ratio and δ56Fe values for the iron ores, reflecting mixing between an igneous Fe end member and an end member that is characterized by a high (>1200) Fe/Ti ratio and low δ56Fe (Fig. 2b). Low δ56Fe values are one of the hallmarks of BIFs that are absent in other bulk geological samples, and are considered to reflect redox processes during deposition of Fe in the water column and subsequent diagenesis in soft sediments4,25.

Depositional age and tectonic affinity of the Yingshan BIF

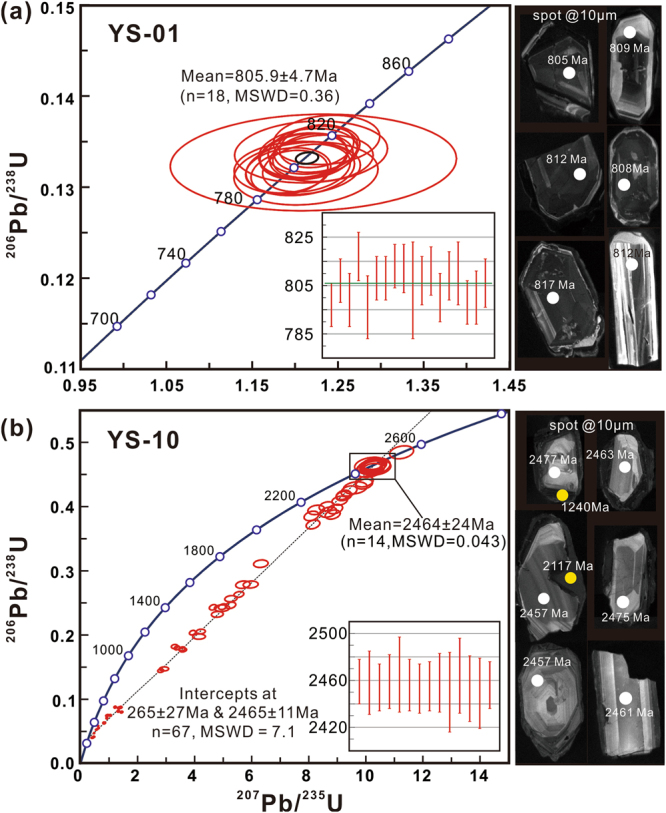

Multiple lines of evidence from texture, chemical compositions and Fe isotope compositions presented above collectively indicate that the protolith for the iron ores from the Yingshan deposit was a banded iron formation, which is referred to as the Yingshan BIF hereafter. The depositional age of the Yingshan BIF is constrained by U-Pb geochronology of zircon grains from the leucosome (YS-10) of a migmatite. The protolith of the migmatite is thought to be a volcanic rock interbedded within the Tongshan volcano-sedimentary sequence and conformably overlying the Yingshan BIF mineralization. Association with volanic rocks is a common feature for Archean BIFs2,3, particularly for Algoma-type BIFs2, and the age of zircons from the volcanic layers interbedded in BIFs have been widely used to constrain the depositional ages of the BIFs26. The zircons from the migmatite leucosome are euhedral with a size of 40–170 μm, and cathodoluminescence (CL) imaging reveals common core-rim textures (Fig. 3). The zircon cores show bright oscillatory CL zoning, and have high Th/U ratio (Th/U = 0.45–1.16), as well as HREE-enriched patterns with positive Ce and Sm anomalies (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. S2), all of which are typical of magmatic zircons27. The rims of the zircon in contrast are dark-gray in CL, have low Th/U values (Th/U = 0.04–0.07) and flat REE patterns without significant Ce and Sm anomalies Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. S2), suggesting a metamorphic origin28. The concordant U-Pb ages for the magmatic zircon cores tightly cluster at 2464 ± 24 Ma (207Pb/206Pb age, n = 14, MSWD = 0.04). The tight distribution of U-Pb ages as well as the irregular shapes of the zircon cores supports the idea that the protolith of the migmatite is a volcanic rock rather than a detrital sediment27,28. Except for an inherited zircon with a concordant207Pb/206Pb age of 2544 Ma (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S5), all the U-Pb analyses of cores and rims of zircon grains from YS-10 define a Discordia with an upper intercept age of 2465 ± 11 Ma and a lower intercept age of 265 ± 27 Ma (n = 67, MSWD = 7.1; Fig. 3). The upper intercept age of the Discordia is consistent with the concordant age (2464 ± 24 Ma) from the zircon cores, representing the age of the volcanic protolith of the migmatite, whereas the lower intercept age reflects an early Mesozoic thermal event that produced the metamorphic rims of the zircon grains. Because of the conformable relationship between the volcanic protolith of the migmatite and the iron formation (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. S1), the Yingshan BIF is interpreted to be approximately coeval with the volcanic protolith of the migmatite corresponding to late Archean-early Paleoproterozoic (2464 ± 24 Ma).

Figure 3.

Zircon U-Pb Concordia and representative cathodoluminesence (CL) images for leucosome (YS-01) and granitoid intrusion (YS-10), respectively.

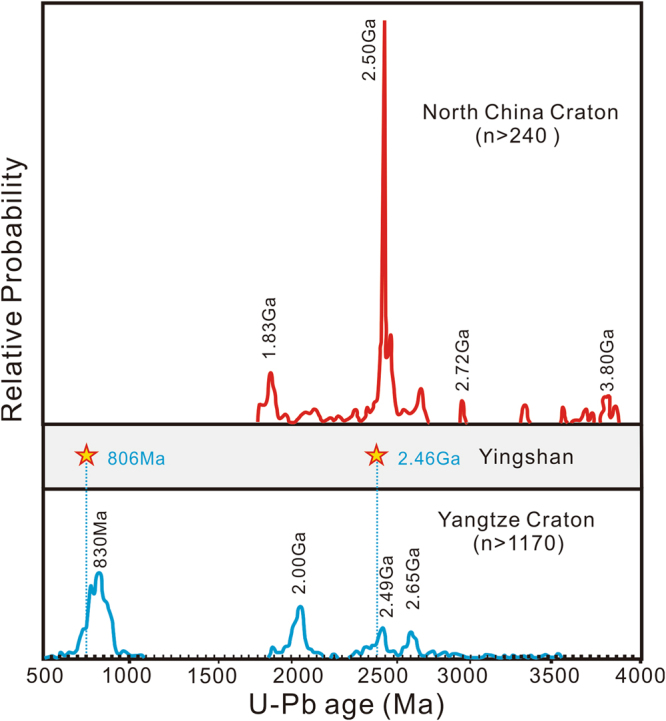

Because the Yingshan iron deposit is located within a major fault zone between the Yangtze Craton and the North China Craton, it is crucial to ascertain the tectonic setting of the BIF protolith. The Yangtze Craton and the North China Craton did not collide until the Triassic17, and the two cratons have distinct Precambrian evolution histories (Fig. 4). The North China Craton is characterized by widespread Archean magmatism that peaked at ~2.5 Ga29,30 and very minor Neoproterozoic magmatic activities in the form of mafic dykes31. In contrast, the Yangtze Craton is characterized by widespread Neoproterozoic magmatism32,33 and ca. 2.0 Ga magmatic events and metamorphism34. The Yingshan iron deposit was intruded by a granitoid pluton (Fig. 1c). Zircon grains from the granitoid (YS-01) are dark gray to gray in color, euhedral to subhedral with a size of 25–150 μm and aspect ratio of 0.5–6.0 (Fig. 3). These zircons show bright oscillatory zoning in CL imaging (Fig. 3) revealing their magmatic origin. U-Pb ages of these magmatic zircons from YS-01 are concordant and yield a weighted mean206Pb/238U age of 805.9 ± 4.7 Ma (n = 18, MSWD = 0.36). The age of the granitoid intrusion is consistent with the magmatism along the northern margin and elsewhere within the Yangtze Craton but is conspicuously absent in the southern margin of the North China Craton. The age data suggest that the Yingshan iron ore bodies were intruded by Neoproterozoic (805.9 ± 4.7 Ma) granitoid prior to the collision between the Yangtze Craton and the North China Craton, thus confirming that the Yingshan BIF belongs to the Yangtze Craton (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of Precambrian detrital zircon U-Pb age spectra between the Yangtze Craton and the North China Craton (modified after30). The U-Pb ages of zircons from the Yingshan iron deposit in this study are represented by stars.

Geological Implications

Based on the geological, geochemical and geochronological evidence presented above, the Yingshan iron deposit is identified as a Neoarchean-Paleoproterozoic banded iron formation and provides a first case of BIF mineralization of such age in the Yangtze Craton. The discovery of the Yingshan BIF indicates that the northern part of the Yangtze Craton was in a shallow marine to continental shelf environment during the late Archean. Occurrence of the late Archean BIF on the northern margin of the Yangtze Craton is in contrast with the linear distribution of Neoproterozoic BIFs in the southern margin of the Yangtze Craton that are indicative of rifting during the Neoproterozoic (Fig. 1a). Such contrast in BIF occurrence seems to reflect a tectonic polarity for the Yangtze Craton, which is interestingly perpendicular to the northern boundary with the North China Craton and the southern boundary with the Cathaysia Block. This feature might have important implications on the patterns of amalgamation and breakup of continents and direction of craton drifting, at least for the case of the Yangtze Craton. The discovery of the Yingshan BIF also places further constraints for understanding the evolution of the Yangtze Craton during the late Archean. The depositional age (~2.46 Ga) of the Yingshan BIF is consistent with the 2.40 ~ 2.55 Ga peak derived from detrital zircon age spectra of the Yangtze Craton30. This is also concordant with the age (2493 ± 19 Ma) of TTG from the basement of the Neoproterozoic Zhangbaling Group, and the age (~2.5 Ga) of the protolith of sheared dioritic-granitic rocks from the Douling complex of southern Qinling orogeny35. Therefore, it is evident that the deposition of the Yingshan BIF was accompanied by a tectono-magmatic event in the Yangtze Craton which also correlates with the global peak in magmatism during the Archean to Paleoproterozoic transition36 (ca. 2.45Ga).

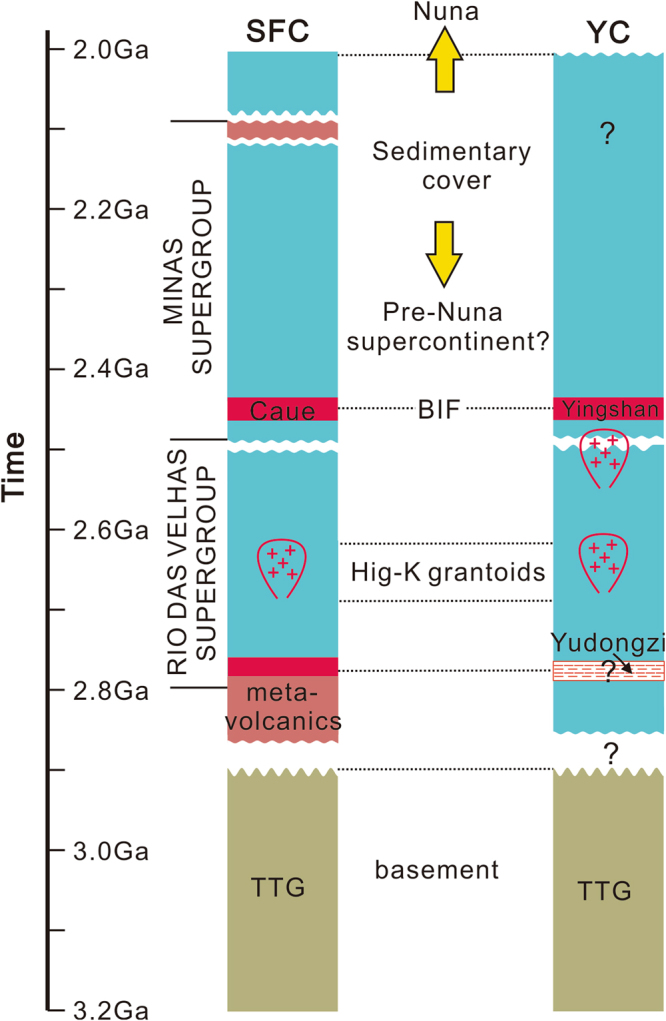

Banded iron formations are considered as important “geologic barcodes” for the reconstruction of supercontinents in Earth’s deep time37–39. For example, the similarity between Archean-Paleoproterozoic BIF records in the Pilbara Craton in Western Australia and the Kaapvaal Craton in South Africa lays the foundation for the idea that these two cratons were once part of a supercraton (the Vaalbara) or the same sedimentary basin40. We note remarkable similarity in the tectonic-sedimentary history between the Yangtze Craton and the Sao Francisco Craton of South America, including a 3.2–2.9 Ga basement of TTG, ~2.7 Ga high-K granitoid magmatic episode, ~2.5 Ga unconformity, ~2.46 Ga BIF (Yingshan and Caue BIFs), 2.4–2.0 Ga sedimentary cover (Fig. 5). Discovery of the Yingshan BIF, therefore, provides additional geological constraints from the Yangtze Craton for further evaluation of the Pre-Nuna/Columbia supercontinents39,41.

Figure 5.

Comparison of stratigraphic-tectonic histories between the Southern Sao Francisco Craton (SF) and the Yangtze Craton (YC).

Methods

Sample preparation

All 23 wall/ore samples collected from the Yingshan iron deposit were cut to remove weathered surfaces. These relatively fresh samples were cleaned, dried and pulverized for compositional analysis. Zircon grains from the leucosome (YS-10) and granitoid (YS-01) sample were separated using standard crushing, heavy liquid, magnetite separation, and hand-picking techniques, then mounted in epoxy resin and polished for U-Pb isotope analysis. All analyses were done in the state key laboratory for mineral deposits research, Nanjing University.

Whole-rock major element and trace element analyses

Whole-rock major elements were analyzed using an ARL9800XP and X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF), which gives the analytical precision better than 2% for all major elements. Whole-rock REEs abundances were measured using a Finnigan Element II ICP-MS and gives precision better than 10% for most REEs. Major element and selected trace element (REE + Y) results are provided in Supplementary Tables S1 and S4.

Whole-rock iron isotope analysis

Approximately 10 to 150 mg bulk-rock powder for each sample was digested in a 2:1:1 mixture of concentrated HCl-HNO3-HF in 7 mL Teflon beaker on hot-plate at ~130 °C for 2 days. After evaporation, the samples were completely dissolved in a 3:1 mixture of concentrated HCl-HNO3 and dried again. The fully dissolved samples were converted to chloride form by repeated redissolution in 1 mL concentrated HCl and subsequent evaporation to dryness. The samples were finally dissolved in 5 mL 7 M HCl and stored in a Teflon beaker as sample stock solution. Based on measured Fe concentrations, an aliquot of the sample stock solution that contained 100 μg Fe was extracted and evaporation to dryness and then dissolved in 100 μL 7 M HCl for chemical purification.

Iron was separated from matrix elements by anion exchange chromatography42 using 0.2 mL Bio-Rad AG MP-1 resin in a custom-made shrinkable Teflon column (4mm ID, 26mm height). Before anion exchange, the resin was cleaned with 1000 μL 2% (volume ratio) HNO3 and 1000 uL Milli-Q H2O, then conditioned with 2000 μL 7 M HCl. After loading 100 μL sample solution in 7 M HCl onto the resin, the matrix elements were eluted off the column using 3 mL of 7 M HCl in 0.5 mL increments. Iron was subsequently eluted from the resin using 3 mL of 2% HNO3. The Fe cut was evaporated to dryness, redissolved in 100 μL sample in 7 M HCl, and was purified for a second time by repeating the anion exchange procedure as described above. Purified Fe was dried and treated with three drops of 30% H2O2 and 2 mL concentrated HNO3 to decompose organic matters. Then Fe was dissolved in 4 mL 2% HNO3 and ready for mass spectrometry analysis. Recovery of Fe for the column procedure was rountinely monitored for each sample by measuring the Fe contents in solutions before and after the ion exchange chromatography using photo spectroscopy (the Ferrozine method), and the Fe recovery was >95%.

Iron isotope ratios were measured using a Thermo Fisher Scientific Neptune Plus MC-ICP-MS at State Key Laboratory for Mineral Deposit Research, Nanjing University. The instrument was running at “wet-plasma” mode using a 100 μL/min self-aspirating nebulizer tip and a glass spray chamber. Molecular interferences of 40Ar14N+ and 40Ar16O+ on 54Fe+ and 56Fe+ were fully resolved using high mass resolution setting of the instrument. Isobaric interference of 54Cr+ on 54Fe+ was monitored by simultaneous measurement of 53Cr+ signals and was corrected offline. Instrument sensitivity was 4–6 V/ppm on 56Fe+ with the instrument setting. A standard-sample-standard bracketing routine was applied for Fe isotope ratio measurement, and samples were diluted to 2 ± 0.2 ppm to match the concentration of an in-house standard that was constant at 2.0 ppm. A 40 s on-peak acid blank was measured before each analysis. Each Fe isotope ratio measurement consisted of fifty 4-s integrations, and the typical internal precision (2standard error or 2SE) was better than ±0.03‰ for 56Fe/54Fe and ±0.05‰ for 57Fe/54Fe. The long-term external reproducibility (2 standard deviation or 2 SD) of Fe isotope analysis is better than ±0.06‰ in 56Fe/54Fe and ±0.16‰ in 57Fe/54Fe over six months, based on repeat analysis of multiple Fe isotope standard solutions against in-house stock solutions.

Iron isotope compositions are reported as δ56Fe relative to the international standard of IRMM-014:

Accuracy of Fe isotope measurements was confirmed by repeated measurements of reference samples and geostandards that were treated as unknowns with the rhyolite samples. δ56Fe of two ultrapure Fe solutions from University of Wisconsin-Madison, J-M Fe and HPS Fe, are 0.37 ± 0.06‰ (n = 10, 2 SD) and 0.58 ± 0.06‰ (n = 7, 2 SD), respectively, which are in excellent agreements with the recommended values22. In addition, the measured Fe isotope compositions of the international whole-rock standards, DNC-1a (δ56Fe = 0.02 ± 0.06‰, n = 3), BCR-2 (δ56Fe = 0.11 ± 0.08‰, n = 9), BHVO-2 (δ56Fe = 0.13 ± 0.05‰, n = 9), BIR-1a (δ56Fe = 0.08 ± 0.06‰, n = 3) and DTS-2b (δ56Fe = 0.06 ± 0.08‰, n = 3), are all consistent with the recommended values43,44 within analytical uncertainties. For igneous rocks investigated in this study, each sample was measured at least three times and analytical uncertainties of Fe isotope ratios were given as 2 SD.

All 23 samples except for YS-52 in this study were analyzed at least two times. Iron isotope results relative to IRMM-014 are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Zircons U-Pb dating and trace element

All grains were imaged using a Mono CL4 Cathode-Luminescence (Gatan, USA) detector on a Zeiss Scanning Electron Microscope (Supra55, Germany). These CL images were used to define the shape and internal structures of the zircons, where suitable locations for laser spot analysis were chosen from (Fig. 3). U-Pb isotope and trace element measurements (Supplementary Tables S5 and S6) were conducted using a GeolasPro193nm ArF Excimer laser ablation system combined with an Element XR high resolution inductively coupled plasma mass-spectrometer (ThermoFisher, USA). Laser ablation was conducted in a helium atmosphere, running with an energy density of 6 J/cm2, a pulse repetition rate of 8 Hz, and a spot size of 10 µm. Each time-resolved laser ablation analysis took about 90 s, including 30 s of gas blank measurement (i.e. on-peak zeros), followed by 40 s of laser ablation and 20 s of washout time to allow the signals to drop back to background levels. Zircon standards 9150045 and GJ-146 were used for calibration and data quality control. Raw data from mass spectrometer were reduced using a Glitter (ver 4.0) software and the U-Pb ages were calculated using Isoplot® (ver 4.15). Common-Pb corrections were carried out prior to U-Pb age calculation using a well established routine of ComPbCorr#3–15 by Andersen (2002)47. The U-Pb isotope and trace element composition of zircons is provided in Supplementary Tables S5 and S6.

Statement of informed consent

Hui Ye appears in Fig. 1d as a scale bar of the orebody and he grants permission on his appearance in this figure.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This manuscript benefits from constructive reviews from F.-X. d’Abzac, and Franco Pirajno. We also thank Dr. Massimo Chiaradia for his editorial handling and constructive comments. This study is supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U1603114 to CZW and No. 41622301 to WL). We thank Xiaopeng Bian, Dehong Du, Xiaoming Wang, Shugao Zhao, Chuan Liu for assistance in field and laboratory.

Author Contributions

C.Z.W., W.L., and T.Y. designed the project. H.Y. and X.Z.Y. performed the geochemical and geochronological analyses. C.Z.W., W.L., T.Y. and H.Y. wrote the manuscript. X.L.W., M. Santosh, and B.F.G. contributed to the scientific discussion.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-15013-4.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chang-Zhi Wu, Email: wucz@nju.edu.cn.

Weiqiang Li, Email: liweiqiang@nju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Barley ME, Bekker A, Krapež B. Late Archean to Early Paleoproterozoic global tectonics, environmental change and the rise of atmospheric oxygen. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2005;238:156–171. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2005.06.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bekker A, et al. Iron formation: The sedimentary product of a complex interplay among mantle, tectonic, oceanic, and biospheric processes. Economic Geology and the Bulletin of the Society of Economic Geologists. 2010;105:467–508. doi: 10.2113/gsecongeo.105.3.467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein C. Some Precambrian banded iron-formations (BIFs) from around the world: Their age, geologic setting, mineralogy, metamorphism, geochemistry and origins. American Mineralogist. 2005;90:1473–1499. doi: 10.2138/am.2005.1871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li W, Beard BL, Johnson CM. Biologically recycled continental iron is a major component in banded iron formations. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of American. 2015;112:8193–8198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505515112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox GM, et al. V. Neoproterozoic iron formation: An evaluation of its temporal, environmental and tectonic significance. Chemical Geology. 2013;362:232–249. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng J, et al. Widespread Archean basement beneath the Yangtze carton. Geology. 2006;34:417–420. doi: 10.1130/G22282.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao GC, Cawood PA. Precambrian geology of China. Precambrian Research. 2012;222–223:13–54. doi: 10.1016/j.precamres.2012.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiu, Y. M., Gao, S., McNaughton, N. J., Groves, D. I. & Ling, W. L. First evidence of ~3.2Ga continental crust in the Yangtze craton of south China and its implications for Archean crustal evolution and Phanerozoic tectonics. Geology28, 11–14, 10.1130/0091-7613(2000)028 (2000).

- 9.Gao S, et al. Age and growth of the Archean Kongling terrain, South China, with emphasis on 3.3 Ga granitoid gneisses. American Journal of science. 2011;311:153–182. doi: 10.2475/02.2011.03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen BF. Geological Characters and Resource Prospect of the BIF Type Iron Ore Deposits in China. Acta Geologica Sinica. 2012;86:1376–1395. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li. HM, et al. Types and general characteristics of the BIF-related iron deposits in China. Ore geology reviews. 2014;57:264–287. doi: 10.1016/j.oregeorev.2013.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C, Konhauser KO, Zhang L. Depositional environment of the Paleoproterozoic Yuanjiacun banded iron formation in Shanxi Province, China. Economic Geology. 2015;110:1515–1539. doi: 10.2113/econgeo.110.6.1515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meert, J. G. & Santosh, M. The Columbia supercontinent revisited. Gondwana Research (in press), 10.1016/j.gr.2017.04.011 (2017).

- 14.Qi RZ. The geology character of Precambrian iron-formation in center Anhui province. Bulletin of Nanjing Institution of Geology and Mineral Resources of Chinese Academy of Geology Science. 1985;6:22–53. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang GW, Yu ZP, Dong YP, Yao AP. On Precambrian framework and evolution of the Qinling belt. Acta Petrologica Sinica. 2000;16:11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng QR, Li SY, Li RW. Mesozoic evolution of the Hefei basin in eastern China: Sedimentary response to deformations in the adjacent Dabieshan and along the Tanlu fault. Geological Society of America Bulletin. 2007;119:897–916. doi: 10.1130/B25931.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao T, Zhu G, Lin S, Wang H. Indentation-induced tearing of a subducting continent: evidence from the Tan–Lu fault zone, East China. Earth-Science Reviews. 2016;152:14–36. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu JW, Zhu G, Tong WX, Cui KR, Liu Q. Formation and evolution of the Tancheng-LuJiang wrench fault system: a major shear system to the northwest of the Pacific Ocean. Tectonicphsicals. 1987;l34:273–310. doi: 10.1016/0040-1951(87)90342-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ewers WE, Morris RC. Studies of the Dales Gorge member of the Brockman iron formation, Western Australia. Economic Geology. 1981;76:1929–1953. doi: 10.2113/gsecongeo.76.7.1929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beard BL, et al. Application of Fe isotopes to tracing the geochemical and biological cycling of Fe. Chemical Geology. 2003;195:87–117. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2541(02)00390-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teng FZ, Dauphas N, Huang S, Marty B. Iron isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2013;107:12–26. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2012.12.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heimann A, Beard BL, Johnson CM. The role of volatile exsolution and sub-solidus fluid/rock interactions in producing high 56 Fe/54 Fe ratios in siliceous igneous rocks. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2008;72:4379–4396. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2008.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Telus M, et al. Iron, Zinc, Magnesium and Uranium Isotopic Fractionation During Continental Crust Diferentiation: The tale from migmatites, granitoids, and pegmatites. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2012;97:247–265. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2012.08.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dauphas N, et al. Clues from Fe isotope variations on the origin of early Archean BIFs from Greenland. Science. 2004;306:2077–2080. doi: 10.1126/science.1104639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson CM, Beard BL, Roden EE. The iron isotope fingerprints of redox and biogeochemical cycling in modern and ancient Earth. Annual Review of Earth Planetary Science. 2008;36:457–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.earth.36.031207.124139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trendall AF, Compston W, Nelson DR, De Laeter JR, Bennett VC. SHRIMP zircon ages constraining the depositional chronology of the Hamersley Group, Western Australia. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 2004;51:621–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1400-0952.2004.01082.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cherniak DJ, Watson EB. Diffusion in zircon. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2003;53:113–143. doi: 10.2113/0530113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoskin PWO, Black LP. Metamorphic zircon formation by solid‐state recrystallization of protolith igneous zircon. Journal of metamorphic Geology. 2000;18:423–439. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1314.2000.00266.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao S, et al. Recycling lower continental crust in the North China craton. Nature. 2004;432:892–897. doi: 10.1038/nature03162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu XM, Gao S, DiWu CR, Ling WL. Precambrian crustal growth of Yangtze craton as revealed by detrital zircon studies. American Journal of Science. 2008;308:421–468. doi: 10.2475/04.2008.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhai M, Hu B, Zhao T, Peng P, Meng Q. Late Paleoproterozoic–Neoproterozoic multi-rifting events in the North China Craton and their geological significance: a study advance and review. Tectonophysics. 2015;662:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tecto.2015.01.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li ZX, et al. Geochronology of Neoproterozoic syn-rift magmatism in the Yangtze Craton, South China and correlations with other continents: evidence for a mantle superplume that broke up Rodinia. Precambrian Research. 2003;122:85–109. doi: 10.1016/S0301-9268(02)00208-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou M-F, Yan D-P, Allen KK, Li Y-Q, Ding J. SHRIMP U-Pb zircon geochronological and geochemical evidence for Neoproterozoic arc-magmatism along the western margin of the Yangtze Block, South China. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2002;196:51–67. doi: 10.1016/S0012-821X(01)00595-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo JL, et al. Episodic Paleoarchean-Paleoproterozoic (3.3–2.0Ga) granitoid magmatism in Yangtze Craton, South China: Implications for late Archean tectonics. Precambrian Research. 2015;270:246–266. doi: 10.1016/j.precamres.2015.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu, J. et al. A ~2.5 Ga magmatic event at the northern margin of the Yangtze craton: Evidence from U-Pb dating and Hf isotope analysis of zircons from the Douling Complex in the South Qinling orogeny. Chinese Science Bulletin58, 3564–3579, 10.1007/s11434-013-5904-1 (2013).

- 36.Heaman, L.M. Global mafic magmatism at 2.45 Ga: Remnants of an ancient large igneous province? Geology25, 299–302, 10.1130/0091-7613 (1997).

- 37.Bleeker, W. The late Archean record: a puzzle in ca. 35 pieces. Lithos71, 99–134, 10.106/j.lithos.2003.07.003 (2003).

- 38.Condie KC, Belousova E, Griffin WL, Sircombe KN. Granitoid events in space and time: constraints from igneous and detrital zircon age spectra. Gondwana Research. 2009;15:228–242. doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2008.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pehrsson SJ, Berman RG, Eglington B, Rainbird R. Two Neoarchean supercontinents revisited: the case for a Rae family of cratons. Precambrian Research. 2013;232:27–43. doi: 10.1016/j.precamres.2013.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheney ES. Sequence stratigraphy and plate tectonic significance of the Transvaal succession of southern Africa and its equivalent in Western Australia. Precambrian Research. 1996;79:3–24. doi: 10.1016/0301-9268(95)00085-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han PY, et al. Widespread Neoarchean (~2.7–2.6 Ga) magmatism of the Yangtze craton, South China, as revealed by modern river detrital zircons. Gondwana Research. 2017;42:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2016.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maréchal CN, Télouk P, Albarède F. Precise analysis of copper and zinc isotopic compositions by plasma-source mass spectrometry. Chemical Geology. 1999;156:251–273. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2541(98)00191-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graddock PR, Dauphas N. Iron isotopic compositions of geological reference materials and chondrites. Geostandards and Geoanalytical Research. 2011;35:101–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-908X.2010.00085.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He Y, et al. High-precision iron isotope analysis of geological reference materials by high-resolution mc-icp-ms. Geostandards and Geoanalytical Research. 2015;39:341–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-908X.2014.00304.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiedenbeck MAPC, et al. Three natural zircon standards for U‐Th‐Pb, Lu‐Hf, trace element and REE analyses. Geostandards newsletter. 1995;19:1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-908X.1995.tb00147.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jackson SE, Pearson NJ, Griffin WL, Belousova EA. The application of laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry to in situ U–Pb zircon geochronology. Chemical Geology. 2004;211:47–69. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2004.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andersen T. Correction of common lead in U-Pb analyses that do not report 204 Pb. Chemical Geology. 2002;192:59–79. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2541(02)00195-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.