Over the past three decades, the prevalence of obesity has markedly increased worldwide, as has the epidemic of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and the complications associated with the two conditions. Since mid-2013, obesity has been recognized as a disease in the United States [1], but such recognition has had no beneficial impact on reducing the stigma attached to obesity. However, the recognition provided a path for appropriate coding and insurance payments for medications and the treatment of obesity, and associated complications [2]. Historically, society has been resistant to accepting “disabilities” as a part of the main stream medicine and medical care. As a result, many such disorders has been pass over to the social services department. Over a three million people with developmental disabilities in the Unites States, who needs both medical and social care is a classic example. The term “obesity” continues to have negative connotations and is associated with stigma, and patients continue to experience prejudice and neglect, and consequent discrimination [3], [4], [5], [6].

In spite of having a genetic susceptibility, obesity is a treatable disease and a chronic disability [7], [8] that presents as a physical or behavioral disorder, or often a combination of both [9]. The increased publicity about T2D and obesity together with the recent health care system changes that extend insurance coverage for the uninsured, hopefully, may plateau or even decrease the incidence of these two major epidemics in the United States, as was seen with cardiovascular diseases two decades ago. This review assesses the intertwined nature of these entities and examines ways to overcome the stigma associated with obesity, which hinders its management and the ability to prevent associated complications.

Changing health care system and obesity

Considering the recent changes in the health care sector, consumers are beginning to acquire (or be forced to think about) self-empowerment—understanding and taking responsibility for one's own health—and the motivation to keep healthy [6], [10], [11]. This new paradigm includes eliminating smoking and decreasing alcohol intake; vegetarianism; eating healthy, organic food and having balanced diets; engaging in physical activity; taking preventative actions such as wearing seat belts in automobiles; understanding the importance of clean air and water; and environmental protection [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. Adhering to these are essential to minimizing the escalating non-communicable diseases.

Obesity is a chronic disability, a treatable disease [17], [18] that presents as both physical and behavioral changes [9], [19], [20]. The broader acceptance of those who are overweight or obese, and management of these disorders are hampered because of the stigma associated with obesity [19]. Many obese patients try to minimize their failure to lose weight by refusing to accept that they are having a problem. In addition, the adherence to weight management interventions is poor [19], [21], [22], [23], in part because of the stigma; management-associated costs; lack of workplace, peer, and family support; and unavailability of affordable quality foods [24]. The mass preparation, processing, and packaging of food, often with the addition of sugar, salt, and preservatives, combined with targeted marketing and food advertising, and changing technologies contribute to the current epidemic of obesity.

Stigma and disabilities

Stigma is a common problem affecting the disabled community [19], [25], [26]. Having a disability, such as a developmental disability or chronic disease including chronic obstructive airway disease, T2D, or obesity, leads not only to physical and mental disabilities, but also to significant economic disadvantages; opportunities are denied and self-esteem suffers [27], [28]. Together these burdens and the societal discriminations aggravate the psychological trauma of stigma. The medical community needs to determine strategically how to overcome these problems that affect more than half of Americans [12].

Obesity is costly and disabling; it is not cool to be obese. Many obese patients feel that they are labeled as unmotivated, lazy, and uncooperative [29]. Although there are psychological and poor motivational elements in obesity, physicians focusing on such do not aid in patients' adherence to advice, pave a path of getting obese patients to lose weight, or prevent obesity-associated complications [19], [21]. The medical community needs to be more sympathetic and compassionate to obese individuals and work with and assist them to lose weight to decrease comorbidities [12].

Stigma of obesity

The stigma associated with obesity is a major psychological and socioeconomic burden for affected persons and their families [7], [27], [30], [31], [32]. It is a major barrier for patients accepting obesity as a disease, and to adhere to effective treatment [26], [30]. Societal changes occur too slowly. Therefore, the medical profession should take the leadership and act promptly to overcome societal stigma associated with obesity as well as other chronic diseases.

Persons who cannot be trusted or who pose a threat to society or its values, such as dictators, murderers, rapists, and robbers have always been stigmatized. However, this should not be the case for individuals with chronic diseases or disabilities such as obesity. Historically, such stigmata were used to keep society safe from illnesses at a time when there was no understanding of the causes of diseases (e.g., tuberculosis). As medical knowledge increased, some of these stigmata disappeared, but those who are chronically ill or disabled, including the obese, continue to be stigmatized. Obesity is not contagious and obese people are not a threat to society; these are some of the unjust and irrational reasons underlying the stigmatization of those who are obese and overweight [3].

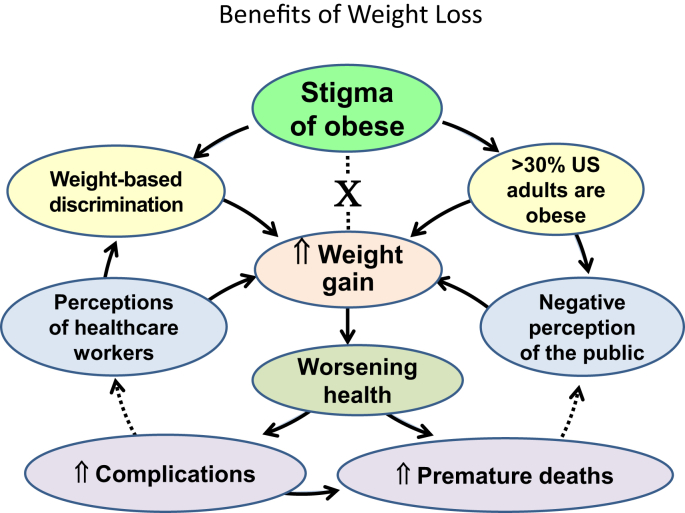

It took a couple of centuries for the society to understand the key differences between communicable (e.g., patients with leprosy, tuberculosis were segregated in sanatoria from the rest of the population) and non-communicable diseases (T2D, myocardial infractions) and recognize that even those with contagious illnesses need acceptance, treatment, and humane care. One can extend this to other medical issues and disorders, such as psychiatric disease, and so-called social diseases such as HIV, alcoholism, addiction, and so forth. Understandably, society take long time to accept these, but the learned medical community needs to lead in expediting the implementation of this process. Physicians are in a unique position to take a leadership role by creating an action plan for understanding, accepting, teaching, and caring for obese patients, just as care provided for patients with other chronic diseases such as osteoporosis and type 2 diabetes that warrant long-term medical care. The figure illustrates how the stigma interferes with the attempts on weight reduction and leads to increase complications and premature deaths (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The figure illustrates how the stigma interferes with the attempts on weight reduction and leads to increase complications and premature deaths.

Responsibility of health care workers

In addition to managing the mind-set of physicians, we need to change the negative attitudes of all health care workers and society toward those who are obese and overweight [33]. Most people do not know how to provide effective care, appropriate understanding and acceptance, and create supportive environments for the obese. This hiatus of understanding needs to be addressed. Supporting this, Puhl et al. reported a high degree of bias among health care workers against overweight and obese patients [34], [35].

Although health care professionals expect to have a better understanding of the causes and necessary expertise to manage patients with obesity, this is not necessarily the case. Many practitioners do not know what to do with their obese patients. In part, due to the slow responses, co-morbidities, and less than expected adherence to advice and therapy, this is not an easy population to work with. Despite the fact that most of the adult population in the Unites States is overweight or obese, including some health care professionals themselves, negative attitudes toward obesity persist. Therefore, the medical profession needs to increase the awareness and provide basic expertise in managing obesity to all healthcare workers, facilitate appropriate referrals, understanding of the multifactorial nature/causes of obesity, and provide options and opportunities to assisting them.

A considerable number of physicians view obesity as largely a behavioral problem caused by mere physical inactivity and overeating [36]. Health care providers perceived obese patients to have reduced self-esteem and sexual attractiveness, and increased weight, primarily because of physical inactivity, food addiction, and personality disorders [37]. Nurses and therapists also have been shown to have negative bias toward obese patients, stereotyping them as lazy, lacking in self-control, and noncompliant [38]. Perhaps, doctors, nurses and therapists should be given additional training to negate their inherent biases including “weight stigma,” similar to that of alcohol and smoking-cessation counseling.

Considering these unfair biases, health care workers should teach the obese and overweight patients, not only practical ways to lose weight, but also how to overcome the psychological consequences and societal stigma, providing techniques for obese people, their families, and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, third party payers, and society to accept obesity as a chronic disease [38], [39], [40].

Meanwhile, physicians and hospital administrators should take the initiative in establishing offices that are friendly to obese patients to help such patients and their families feel comfortable (examples include providing easier access, larger chairs and wheel chairs, and larger gowns and blood pressure cuffs) [41], [42]. Health care providers should break the negative vicious cycle of unconstructive expectations by recognizing and encouraging patients' weight management efforts.

Physicians should support patients to set their personal goals and understand patients' needs, expectations, and experiences [43], [44]. A key question is: Does a busy, practicing physician today have the time to deliver such real and meaningful care to patients? Will the medical insurance system's coverage appropriately accommodate the time spent by health care workers in educating and supporting patients with chronic diseases, including obesity?

Societal responsibility

Individuals in medical and social interactions have the responsibility to make the other person feel comfortable; this is a two-way process. No one is perfect, and we need to recognize the value of each human being. However, obese patients also need to accept certain realities and take firm responsibility for their own behavior. Considering the escalating epidemic of obesity worldwide, initiating a nationwide, culturally-accepted, medico-social campaign to overcome obesity-associated stigma and encouraging healthy life-styles are timely. Such fundamental approaches would be more cost-effective than all medical and surgical treatment for obesity put together.

Such a campaign would encourage more obese and overweight patients to seek the care they deserve, adhering to medical advice and treatments, and take personal responsibility to prevent future complications. Doing so would enable them to overcome the physical, mental, and psychological challenges of obesity, and re-gain self-respect. The campaign would also strengthen family and workplace support for those attempting to lose weight and maintain a healthy weight, which would also improve the school and workplace performance and minimize the absentees. It is important for physicians to extend the best possible care to their patients, helping them to understand, manage, and cope with this chronic disease. However, the changes need to start within physicians first.

Patient responsibilities

Those who are stigmatized also need to shoulder certain responsibilities. Some people argue that tolerance leads to acceptance of inappropriate standards or behavior [45], [46], [47]. However, the patients' views and attitudes are often misinterpreted because of stereotyping, which hinders overcoming stigma and establishing fruitful collaborations [26], [30], [38]. Meanwhile, educating the overweight and obese should encompass information on body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference, curtailing smoking and alcohol consumption, healthy eating, balanced nutrition, physical activity, and adherence to advice and management. All these are directed to, improve the well-being and to reduce the complications associated with obesity. Some obese patients perceive ‘self-stigma’ due to their appearances such as those with sarcopenic obesity with resulting postural issues. Motivations to continue lifestyle interventions incorporating both diet-induced weight loss and regular exercise seems to be a good option for these patients than embarking on expensive medications with little benefit (NEW REF: Bouchonville, M. F., Villareal, D. T. Sarcopenic obesity: how do we treat it? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes., 2013, 20: 412-19.). However, because of the expectations and the build-in payment systems, none of these going to work efficiently without appropriate compensation for the health care workers who take care of the obese. Moreover, all of these aspects have a direct or indirect impact on practicing physicians, obesity specialists, clinical endocrinologists, and all other health care workers, in (A) their ability to care for patients without too many restrictions, (B) continuing the quality of care provided, and (C) achieving meaningful outcomes for patients.

Conclusions

There are thousands of physical, behavioral, and psychological disorders that physicians label into “disease groups,” yet the “sickness experience” is unique for each patient. Nevertheless, only a few health care workers, such as palliative experts, truly understand the patient's perspective [34], [48]. Although obesity is a medical and a psychological disorder with a genetic trait, it affects the person more than this [26]. For example, it lessens an individual's social, educational, and economic opportunities, curtails the ability to earn a living and free mobility, and impairs social interactions, identity, interactions with their partners and the society, and self-esteem [20], [39]. Some of these can be surmounted easily, but not necessarily the social stigma. Stigma is in the mind; it ignores all good qualities of an affected person, but focus only on one aspect of the individual. Unfortunately, the media often makes the stigma of obesity worse. However, media also has great potential to change society in a positive manner.

Type 2 diabetes and obesity are interlinked. Considering that more than 65% of Americans are overweight or obese, the traditional approach of treating each individual component, such as lipid disorders, hypertension, and insulin resistance, is becoming cost-prohibitive [49]. Instead of treating individual signs and symptoms of obesity, one should attempt to identify root causes that lead to weight gain and obesity in an individual patient (as with other chronic diseases, such as identifying and treating secondary causes for osteoporosis), and then focus the treatment to minimize or eliminate the cause(s) and an individual's risk factor(s) with the view of the preventing future complications [9], [21]. With the escalating U.S. budget deficit, shrinking Medicare dollars [50], and similar financial constraints on health care budgets in most other countries, the implementation of cost-effective approaches to chronic disease management is essential [21].

Adherence to weight reduction interventions is poor [51], [52]. This is attributable in part to the costs of management, ineffective peer and family support, unavailability of affordable quality foods, lack of physical activity, and social stigma. Adherence to treatment by the obese can be improved by (A) overcoming the stigma, (B) new Evaluation and Management Coding for billing and appropriate medical insurance coverage (obesity-rehabilitation, just like cardiac-rehabilitation), and (C) the use of proper motivating messages for weight loss and weight maintenance. Such messages should focus on healthy behavioral changes and not on body weight, BMI or obesity. This is yet another way to minimize the stigma and achieve weight loss goals.

Social pressures and biased attitudes toward the obese are not rare in the health care sector, worldwide. These are, attributable in part to the health care community's attempt to shift responsibility for obesity and ill health to patients, and are perceived by patients. The time spent with physicians and the effectiveness of counseling and treatments received by the obese and overweight people are somewhat inferior because of weight bias and stereotypical assumptions in health care settings [53]. Many health care workers continue to have negative attitudes toward obese patients, including beliefs that obese patients are lazy, noncompliant, undisciplined, and have low willpower [34], [35], [54]. Consequently, the prevalence of weight-based discrimination is increasing [55] and is not that different from rates of racial discrimination [56].

Summary

Health care workers need to embrace new concepts, collaborate with other care partners, and focus on cause-driven approaches [9], [21] to overcome the obesity epidemic, and develop strategies to minimize obesity-associated stigma. It is irrational and in fact cost-prohibitive in the long term to treat each sign and complication of obesity. Thus, instead of waiting for complications to occur and then treat, cause-oriented approaches is necessary to early identification of reasons for weight gain in a given patient and focus attention on preventing obesity complications by preventing and/or reversing such weight gain [9], [21]. In addition, health care workers, insurance and third party payers, and the politicians need to listen to people, observe trends, and lead the change when appropriate so that physicians can continue what they do best: provide the best possible care for their patients, even under ever-increasing commitments and resource constraints.

The stigma associated with obesity is a major barrier to accepting it as a disease by patients and thus to treatment; therefore, the stigma needs to be eliminated [26]. Stigma is also a major psychological and socioeconomic burden in the workplace and classrooms, affecting overweight and obese persons, and their families. The medical profession needs to lead by taking effective actions to overcome this societal stigma, in persons who are overweight or obese and those with other chronic diseases.

Footnotes

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/).

Funding: None.

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

- 1.Beal E. The pros and cons of designating obesity a disease: the new AMA designation stirs debate. Am J Nurs. 2013;113:18–19. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000437102.45737.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson S.S. Obesity in Tennessee: the policy implications of labeling obesity as a “disease”. Tenn Med. 2014;107:27–28. 30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puhl R.M., King K.M. Weight discrimination and bullying. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkelstein E.A., Khavjou O.A., Thompson H., Trogdon J.G., Pan L., Sherry B. Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sturm R. Increases in morbid obesity in the USA: 2000-2005. Public Health. 2007;121:492–496. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prochaska J.O., Velicer W.F. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12:38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith E., Hay P., Campbell L., Trollor J.N. A review of the association between obesity and cognitive function across the lifespan: implications for novel approaches to prevention and treatment. Obes Rev. 2011;12:740–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen N., Champion J.K., Ponce J., Quebbemann B., Patterson E., Pham B. A review of unmet needs in obesity management. Obes Surg. 2012;22:956–966. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0634-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wimalawansa S.J. Pathophysiology of obesity: focused, cause-driven approach to control the epidemic. Global Adv Res J Pharm Pharmacol. 2013;2:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armitage C.J., Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol. 2001;40:471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terry D.J., O'Leary J.E. The theory of planned behaviour: the effects of perceived behavioural control and self-efficacy. Br J Soc Psychol. 1995;34(Pt 2):199–220. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1995.tb01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wimalawansa S.J. Visceral adiposity and cardio-metabolic risks: epidemic of abdominal obesity in North America. Res Rep Endocr Disord. 2013;3:17–30. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Surgeon-General. Call to action to prevent and decrease overweight and obesity. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20669513. 2001. Rockville (MD) [PubMed]

- 14.Surgeon-General Fact sheets from the Surgeon General's call to action to prevent and decrease overweight and obesity. W V Med J. 2002;98:234–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NHLBI NIoH Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults–the evidence report. National Institutes of health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NHLBI NIoH Executive summary of the clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1855–1867. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.17.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alley D.E., Chang V.W., Doshi J. The shape of things to come: obesity, aging, and disability. LDI Issue Brief. 2008;13:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lebrun C.E., van der Schouw Y.T., de Jong F.H., Grobbee D.E., Lamberts S.W. Fat mass rather than muscle strength is the major determinant of physical function and disability in postmenopausal women younger than 75 years of age. Menopause. 2006;13:474–481. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000222331.23478.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puhl R.M., Brownell K.D. Confronting and coping with weight stigma: an investigation of overweight and obese adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1802–1815. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wimalawansa S.J. Thermogenesis based interventions for treatment for obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2013;8:275–288. doi: 10.1586/eem.13.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wimalawansa S.J. Controlling obesity and its complications by elimination of causes and adopting healthy habits. Adv Med Sci. 2014;3:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Douketis J.D., Macie C., Thabane L., Williamson D.F. Systematic review of long-term weight loss studies in obese adults: clinical significance and applicability to clinical practice. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:1153–1167. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aucott L., Poobalan A., Smith W.C., Avenell A., Jung R., Broom J. Weight loss in obese diabetic and non-diabetic individuals and long-term diabetes outcomes–a systematic review. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2004;6:85–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-8902.2004.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown I., McClimens A. Ambivalence and obesity stigma in decisions about weight management: a qualitative study. Health. 2012;4:1562–1569. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman J.M. Modern science versus the stigma of obesity. Nat Med. 2004;10:563–569. doi: 10.1038/nm0604-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malterud K., Ulriksen K. Obesity, stigma, and responsibility in health care: A synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2011;6:10–19. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v6i4.8404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman K.E., Ashmore J.A., Applegate K.L. Recent experiences of weight-based stigmatization in a weight loss surgery population: psychological and behavioral correlates. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(Suppl 2):S69–S74. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gortmaker S.L., Must A., Perrin J.M., Sobol A.M., Dietz W.H. Social and economic consequences of overweight in adolescence and young adulthood. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1008–1012. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wellman N.S., Friedberg B. Causes and consequences of adult obesity: health, social and economic impacts in the United States. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2002;11(Suppl 8):S705–S709. [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeJong W. The stigma of obesity: the consequences of naive assumptions concerning the causes of physical deviance. J Health Soc Behav. 1980;21:75–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeJong W. Obesity as a characterological stigma: the issue of responsibility and judgments of task performance. Psychol Rep. 1993;73:963–970. doi: 10.1177/00332941930733pt136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crandall C., Martinez R. Culture, ideology and anti-fat attitudes. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1996;22:1165–1176. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muller R. Psychological consequences of obesity. Ther Umsch. 2013;70:87–91. doi: 10.1024/0040-5930/a000371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brownell K.D., Schwartz M.B., Puhl R.M., Henderson K.E., Harris J.L. The need for bold action to prevent adolescent obesity. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:S8–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puhl R.M., Heuer C.A. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:941–964. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foster G.D., Wadden T.A., Makris A.P., Davidson D., Sanderson R.S., Allison D.B. Primary care physicians' attitudes about obesity and its treatment. Obes Res. 2003;11:1168–1177. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harvey E.L., Hill A.J. Health professionals' views of overweight people and smokers. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1253–1261. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown I. Nurses' attitudes towards adult patients who are obese: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53:221–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okechukwu C.A., Souza K., Davis K.D., de Castro A.B. Discrimination, harassment, abuse, and bullying in the workplace: contribution of workplace injustice to occupational health disparities. Am J Ind Med. 2013;57:573–586. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogden J., Bandara I., Cohen H., Farmer D., Hardie J., Minas H. General practitioners' and patients' models of obesity: whose problem is it? Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44:227–233. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greiner K.A., Born W., Hall S., Hou Q., Kimminau K.S., Ahluwalia J.S. Discussing weight with obese primary care patients: physician and patient perceptions. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:581–587. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0553-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.wadden T.A., An-derson D.A., Foster G.D., Bennett A., Steinberg C., Sarwer D.B. Obese women's perceptions of their physicians' weight management attitudes and practices. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:854–860. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.9.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Editors PLM Qualitative research: understanding patients' needs and experiences. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown I., Gould G. Decisions about weight management: a synthesis of qualitative studies of obesity. Clin Obes. 2011;1:99–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-8111.2011.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas S.L., Hyde J., Karunaratne A., Herbert D., Komesaroff P.A. Being 'fat' in today's world: a qualitative study of the lived experiences of people with obesity in Australia. Health Expect. 2008;11:321–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wee C.C., Davis R.B., Huskey K.W., Jones D.B., Hamel M.B. Quality of life among obese patients seeking weight loss surgery: the importance of obesity-related social stigma and functional status. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:231–238. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2188-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bouchonville M.F., Villareal D.T. Sarcopenic obesity: how do we treat it? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20:412–419. doi: 10.1097/01.med.0000433071.11466.7f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scheepmans K., Dierckx de Casterle B., Paquay L., Van Gansbeke H., Boonen S., Milisen K. Restraint use in home care: a qualitative study from a nursing perspective. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loveman E., Frampton G.K., Shepherd J., Picot J., Cooper K., Bryant J. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of long-term weight management schemes for adults: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15:1–182. doi: 10.3310/hta15020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wimalawansa S.A., WSJ . 2013. United States financial crisis: causes and solutions.http://www.srilankaguardian.org/search/label/Sunil%20Wimalawansa [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bouchonville M., Armamento-Villareal R., Shah K., Napoli N., Sinacore D.R., Qualls C. Weight loss, exercise or both and cardiometabolic risk factors in obese older adults: results of a randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;38:423–431. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Finley C.E., Barlow C.E., Greenway F.L., Rock C.L., Rolls B.J., Blair S.N. Retention rates and weight loss in a commercial weight loss program. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:292–298. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Forhan M., Salas X.R. Inequities in healthcare: a review of bias and discrimination in obesity treatment. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.03.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Puhl R., Brownell K.D. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9:788–805. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andreyeva T., Puhl R.M., Brownell K.D. Changes in perceived weight discrimination among Americans, 1995-1996 through 2004-2006. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1129–1134. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Puhl R.M., Andreyeva T., Brownell K.D. Perceptions of weight discrimination: prevalence and comparison to race and gender discrimination in America. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:992–1000. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]