Abstract

The magnetic characteristics of hemoglobin (Hb) changes with the binding of dioxygen (O2) to the heme prosthetic groups of the globin chains: from paramagnetic ferrous Hb to diamagnetic ferrous oxyhemoglobin (oxyHb) with reversibly bound O2, or paramagnetic ferric methemoglobin (metHb). When multiplied over the number of Hb molecules in a red blood cell (RBC), the effect is detectable through motion analysis of RBCs in a high magnetic field and gradient. This motion is referred to as magnetophoretic mobility which can be conveniently expressed as a fraction of the cell sedimentation coefficient. In this report, using a previously developed and reported instrument, cell tracking velocimetry (CTV), we are able to detect difference in Hb concentration in two RBC populations to a resolution of 1 × 107 Hb molecules per cell (4 × 107 atoms of Fe per cell, or 4 – 5 femtograms of Fe). Similar resolution achieved with Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry requires on the order of 105 – 106 cells and provides an average, whereas CTV provides a measurement for each cell. CTV analysis revealed that RBCs lose, on average, 16% of their Hb after 42 days of storage over the maximum FDA-approved length of time for the cold storage of RBCs in additive solution. This difference in Hb concentration was the result of routine RBC storage; clinical implications are discussed.

TOC image

Introduction

Iron (Fe) is one of the top ten most abundant elements in the universe and an essential trace element for nearly all forms of life.1 Fe’s ability to readily accept or donate electrons not only makes Fe fundamental to metabolic pathways but also results in it being highly reactive and potentially toxic. Nature provides a wide range of proteins and prosthetic groups contained in proteins to tightly control Fe within cells; hemoglobin (Hb) likely to be the most well-known; however, the Fe storage protein, ferritin, is actually more ubiquitous across the animal kingdom.2 To provide context, Table 1 lists average values of reported Fe content for a number of different cell types.

Table 1.

Estimated, average values of Fe content in various types of cells

| Cell type | # atoms/cell | Concentration in cell | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | 105–106 | 1.6 × 10−3 M | 3 |

| K562 | 3.6 × 107 | 3.0 × 10−5 M | 4 |

| T. pseudonana | 2.7 × 107 | 4.5 × 10−4 M | 5 |

| Human red blood cell | 1.1 × 109 | 2.0 × 10−2 M | 6 |

Magnetism originates at the atomic level and is considered a specific, quantum-mechanical phenomenon. Paramagnetism, and its contrasting behavior, diamagnetism, which is one type of magnetism is the fundamental phenomena used to track red blood cells (RBCs) in this study. Both types of magnetism only occur in the presence of an externally applied magnetic field (this external field induces a magnetic moment in the Fe containing material of interest). This is in contrast with the more commonly experienced ferromagnetism which exists without an externally applied magnetic field. When an externally applied field has a gradient, a resulting attractive (paramagnetic) or repulsive (diamagnetic) force occurs on this magnetic moment.

Most of the common transition metal atoms, and the corresponding molecules containing the transition atoms, in biological systems are diamagnetic; the exceptions being Fe and manganese (Mn). This ready ability of Fe and Mn to accept or donate electrons (i.e. their easily changeable oxidation states, and in the case of Fe in Hb, the interchanging of a covalent bond with O2 and an ionic form of Fe) results in the potential to transition to an unpaired electron state and consequently, acquire paramagnetic properties. In 1936 and 1937, Linus Pauling and coworkers reported that the chemical bond between the Fe atom and the porphyrin ring in Hb changes from an ionic bond in the deoxygenated state to a covalent bond in the oxygenated state.7,8 In the 2+ valence state, the heme Fe (Fe2+) has unpaired electrons, which gives deoxygenated Hb (deoxyHb) paramagnetic characteristics in contrast to the diamagnetic character of the covalent Fe bonds in oxygenated Hb (oxyHb). They further noted that methemoglobin (metHb, i.e. oxidized Hb), which can be synthesized by oxidizing Hb, is similarly paramagnetic.

The importance of heme in Hb, and more generally the importance of RBCs carrying O2 to tissues, is obvious. RBC transfusion is clinically used to treat hemodynamic instability and O2-carrying deficits in patients with acute blood loss and patients with chronic anemia caused by bone marrow failure/suppression.9–12 Currently, cold storage of human RBCs (hRBCs) in FDA-approved storage solutions can preserve hRBCs for a maximum of six weeks (i.e. 42 days).13 Despite widespread clinical use of maximally stored RBC, in theory, adverse clinical events might occur in recipients of longer stored RBCs.14–20 The supply of RBCs is expected to diminish as the population base ages and demand increases.9,21–23 As the stored RBCs age, they undergo biochemical and biophysical changes that are often collectively referred to as the storage lesion,24–30 which has been a subject of significant number of recent clinical studies, including three large, randomized controlled trials that did not show any adverse clinical effects of transfusing longer stored RBCs in a variety of patient populations.31–33 Using this change in the RBCs’ magnetic properties between the oxygenated, deoxygenated, and met form of Hb, Jin et al. reported that the magnetic susceptibility of RBCs changes during ex vivo storage, and they suggested this change in magnetic susceptibility is a result in changes in the affinity of Hb for O2 or loss of Fe/Hb from the RBCs.34 In this study, we wish to demonstrate from first principle relationships of independently known physical properties and experimental measurements, that statistically significant estimates of the concentration of Fe within RBCs at the resolution of 5 × 10−15 g of Fe per cell can be made, clearly demonstrating the loss of Fe, and presumably Hb with increasing ex vivo storage time.

Method of magnetophoretic analysis by cell tracking velocimetry

Governing equations

The magnetically induced velocity of a cell or particle, suspended in a fluid, is represented by:

| (1) |

where

| (2) |

H and B0 are the magnetic field strength and flux density of the source, χRBC and χf are the magnetic susceptibilities of the dispersed phase (RBC) and continuous phase (suspending fluid), VRBC is the volume of the RBC, DRBC is the hydrodynamic diameter of the cell, and η is the viscosity of the suspending fluid. These derivations apply to the magnetic field gradient in one dimension.34

An analogous relationship applies to the settling velocity, us, of a cell or particle:

| (3) |

where g is the gravitational acceleration (the sedimentation driving force), and ρRBC and ρf are the mass densities of the RBC and suspending fluid, respectively. Assuming that the suspending fluid is a dilute electrolyte solution in water so that ρf = ρH2O and χf = χH2O, and dividing Equation 1 by 3, one obtains:

| (4) |

(Note: the ratio of um/us is independent of the size (diameter) of the cell; it is only a function of the cell density and the magnetic susceptibility).

Rearranging Equation 4, the magnetic susceptibility of each RBC is only a function of the experimentally measured ratio, um/us, and the density difference, ∆ρ, between the cell and the suspending fluid.

| (5) |

Further, χRBC can be mathematically related to the concentration of Hb inside the RBC, cHb, with the following relationship where the constants are independently known (Jin et al. 2011):34

| (6) |

Vm,Hb = 48.23 L/mol is the molar volume of Hb, χm,globin = −37,830 × 10−9 L/mol is the molar susceptibility of the globin chain, and χH2O = −12.97 × 10−9 L/mol is the molar susceptibility of water. The molar susceptibility of the deoxygenated Hb heme group is χm,deoxyHb = 50,890 × 10−9 L/mol, and that of metHb heme group is χm,metHb = 56,000 × 10−9 L/mol (all in CGS system of units). The molar susceptibility of the oxyHb heme group is zero. Note: the magnetic susceptibilities in Equation 5 are volume magnetic susceptibilities (dimensionless) whereas those in Equation 6 are molar magnetic susceptibilities (in L/mol). The conversion factor is equal to the mass density divided by the molecular weight ratio, 0.021 mol/L for Hb and 55.6 mol/L for water. In addition, the same system of electromagnetic units is used for susceptibility values in Equations 5 and 6. The conversion factor is 4π from CGS to SI system of units.

Up through the derivation of Equation 6, the size of the RBC was not needed; however, in Equation 6, the concentration of Hb is reported in units of mol/L. To determine the amount of Hb per cell, the volume of the specific cell is needed. If one makes the assumption that RBC becomes spherical with storage (a common assumption with visual verification)14, Equations 3 through 6 can be combined to give:

| (7) |

Accuracy of magnetic susceptibility measurements

With respect to the magnetic susceptibility estimate of a CTV-tracked RBC (Equation 5), two types of accuracy can be considered: the average value of magnetic susceptibility of the population evaluated and the distribution around this mean value. Previous publications on the use of the CTV instrument have involved measurements of magnetic particles, polystyrene microbeads (PSM), and magnetically labeled and unlabeled cells.

While calibration particles can be purchased for size measurement tests, we know of no particles sold with the express purpose of calibrating magnetic susceptibility measurements. A previous publication (Nakamura et al.) demonstrated close agreement between the manufacturer’s specifications, coulter counter measurements, and the CTV instrument with respect to size and standard deviation of calibration beads of three different sizes (Equation 3).35 The supplemental information presents this comparison.

With respect to measurements of the intrinsic magnetic susceptibility of particles/cells, we have previously reported that the CTV instrument can accurately estimate the magnetic susceptibility of the diamagnetic PSMs to be −0.80 × 10−5 or −0.77 × 10−5 (two independent studies), while other independently reported values are −0.75 × 10−5 and −0.82 × 10−5.36, 37 However, we did not report the distribution around these reported mean values, nor our ability to accurately differentiate the difference in magnetic susceptibilities between two different populations.

To estimate the potential propagation of error in estimating the magnetic susceptibility of a RBC, Equation 5 is of the general form:

| (8) |

where , ∆ρ, and Sm, are experimentally determined/measured. The quotient, , used in Equation 5 and 8 is actually the x and y vector components of the single overall velocity determined by the CTV software.

From the principle of error propagation, the coefficient of variation, of the magnetic susceptibility measurements can be estimated:

| (9) |

The value of Sm in the CTV system is based on computer models and experimental validation at specific locations. Based on these studies, a maximum CVSm of 0.035 can be assigned to the current system. For this current study with RBCs, Jin et al. measured the density of RBCs over ex vivo storage time and noted a maximum 0.5% change drop on day 42 of storage, which corresponds to a CVρ of 0.0045. In contrast, as might be expected, the greatest potential of variation is in the CTV-determined cell velocity ratio, .

To obtain a measure of this variation, Table 2 presents the means, standard deviation, 95% confidence interval, CI, and CV of from previous publications. PSM or commercial magnetic particles are presented assuming that the magnetic susceptibility of the material in these particles is more uniform than cells. The CVs of these four selected samples ranged from 0.21 to 0.32, which confirms that the ratio, , is the primary contributor to the variability in the magnetic susceptibility measurements (the CV for is much higher than the other CVs in Equation 9).

Table 2.

Selected ratios of magnetic to settling velocity measured by the CTV instrument from previous publications.37, 38 Only data using either commercial magnetic particles or PSM are presented, assuming that the magnetic susceptibility of the material in these particles is more uniform than cells.

| Sample | Um/Us | Stdev | 95% CI | CV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dyna M-450 (60 wt% glycerol) | 46 | 11 | 0.40 | 0.24 | |

| Dyna M-280, 0.02A | 0.53 | 0.12 | 0.008 | 0.23 | |

| Dyna M-280, 0.06A | 4.3 | 1.4 | 0.084 | 0.32 | |

| Dyna M-280, 0.14A | 18 | 3.8 | 0.26 | 0.22 | |

| PSM, in buffer | −28 | 19 | 0.69 |

Experimental section

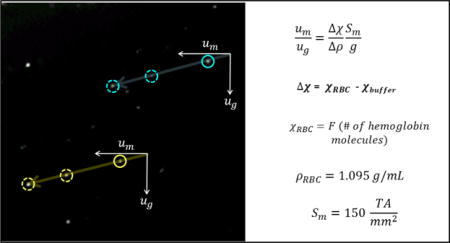

Figure 1 presents a previously published screen shot of oxygenated, 1A, and metHb form of RBCs, 1B, obtained in the CTV instrument which allows individual cells to be tracked microscopically in a nearly constant, well-defined, magnetic energy gradient, Sm.34 In this field of view (FOV), the force of gravity operates in the vertical direction, and the value of Sm (Equation 2) is constant and operates in the horizontal direction.39, 40 For the CTV instrument configuration reported in this study, the magnetic field parameters were Sm = 150 tesla.ampere/mm2 ± 0.7% (150 × 10−6 joule/mm4 ± 0.7%), the mean magnetic field value was 1.40 T, and the mean field gradient was 0.131 T/mm over the FOV. The standard gravitational acceleration is g = 9.81 m/s2, resulting in g/Sm = 6.54 × 10−8 m3/kg. The volume magnetic susceptibility of the suspending fluid was taken as equal to that of water, χf = −9.035 × 10−6 (in SI system of units). The different (higher) magnetically induced velocity of the metHb form of RBCs (Figure 1B) is qualitatively observable by the approximate 45 degree angle of the tracks (settling velocity in vertical direction, magnetically induced velocity in the horizontal direction). The CTV software is capable of tracking on the order of hundreds to thousands of cells, and for the experiments presented in this report, greater than 1,200 RBCs were tracked per experimental condition.

Figure 1.

Examples of the computer screen output of the CTV software showing the motion trajectories of A) oxyHb RBCs (note the virtual absence of magnetophoretic movement along the horizontal axis) and B) metHb RBCs (from Jin et al. 2010).34

The method of obtaining and processing the human RBC samples has also been previously reported and will only briefly be presented here.34 Four pre-storage leukoreduced human RBC units in AS-5 solution were obtained from a local FDA-licensed blood center and stored between 1 – 6 °C for 42 days. This protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s institutional review board. A 5 mL sample was removed using sterile technique weekly starting on day 7 of storage. This sample was divided into three aliquots designated “oxyHb RBC,” “metHb RBC,” and “deoxyHb RBC.”

To obtain oxyHb RBCs for analysis, 0.1 mL of RBCs removed from the storage bag and placed in 4.9 mL PBS was exposed to room air for approximately 10 minutes. Subsequently, 1.5 × 106 oxyHb RBCs were added to 4 mL PBS containing 0.1% Pluronic F-68 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) in preparation for CTV analysis.

To obtain metHb RBCs for analysis, a 5 mM oxidant solution was prepared by dissolving sodium nitrite (NaNO2, Sigma-Aldrich Co., Milwaukee, WI) in PBS at room temperature. 2 × 106 RBCs were pelleted and resuspended in 5 mL of the 5 mM sodium nitrite solution, which was then incubated for about 1.5 hours to achieve a 100% metHb oxidation.

To obtain deoxyHb RBCs for analysis, a Glove-Bag inflatable glove chamber (Cole Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL), filled with nitrogen (Medipure nitrogen, concentration > 99%, Praxair, Inc., Danbury, CT) and tightly sealed, was used to deoxygenate RBCs. The nitrogen gas was humidified by bubbling through water. 2 × 106 RBCs in 5 mL PBS were stored in an inclined 50 mL conical tube affixed to a stirring rotator, which was kept in the N2 atmosphere for 3 hours.

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the reliability of the CTV system, the means and standard deviations (STD) of the ratio of induced velocities, um/us, from the particles in each sample, and the repeated measures from the same sample, as well as the coefficient of variance (CV=STD/average ratio) for each sample were calculated. The changes of the ratios over time for each sample were estimated using the 2-sample t-test.

Results and discussion

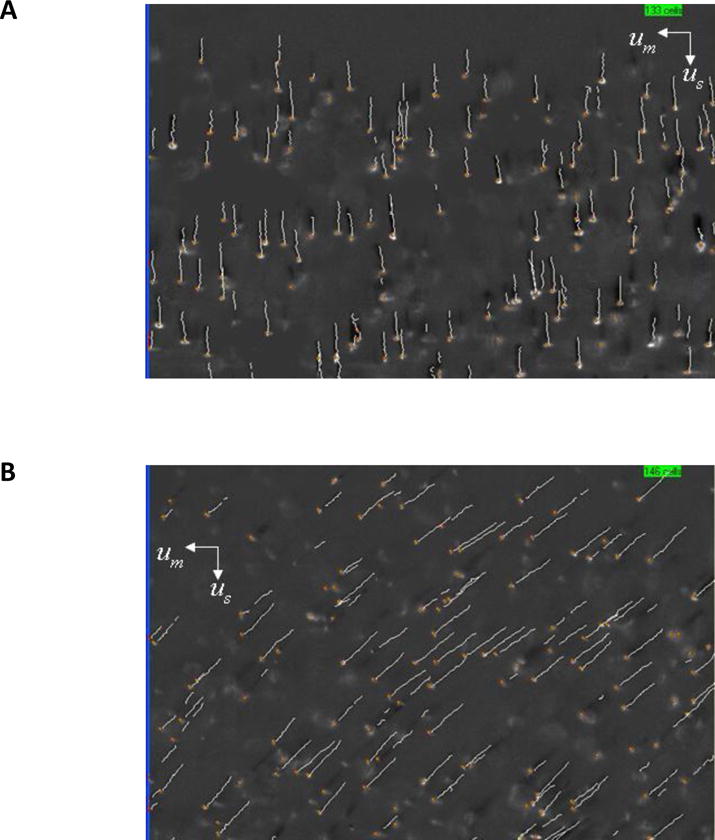

Figure 2 presents histograms of the magnetically induced velocity of deoxygenated RBCs for the same specific donor after 14, 28, and 42 days of storage. As a point of comparison, a histogram of the settling velocity of these same RBCs at 14 days is presented as an inset histogram.

Figure 2.

Representative histograms of the magnetically induced velocity of deoxygenated RBCs for the same specific donor after 14, 28, and 42 days of storage, 2A, 2B, and 2C, respectively. As a point of comparison, a histogram of the settling velocity of these same RBCs at 14 days is presented as an inset histogram in 2A.

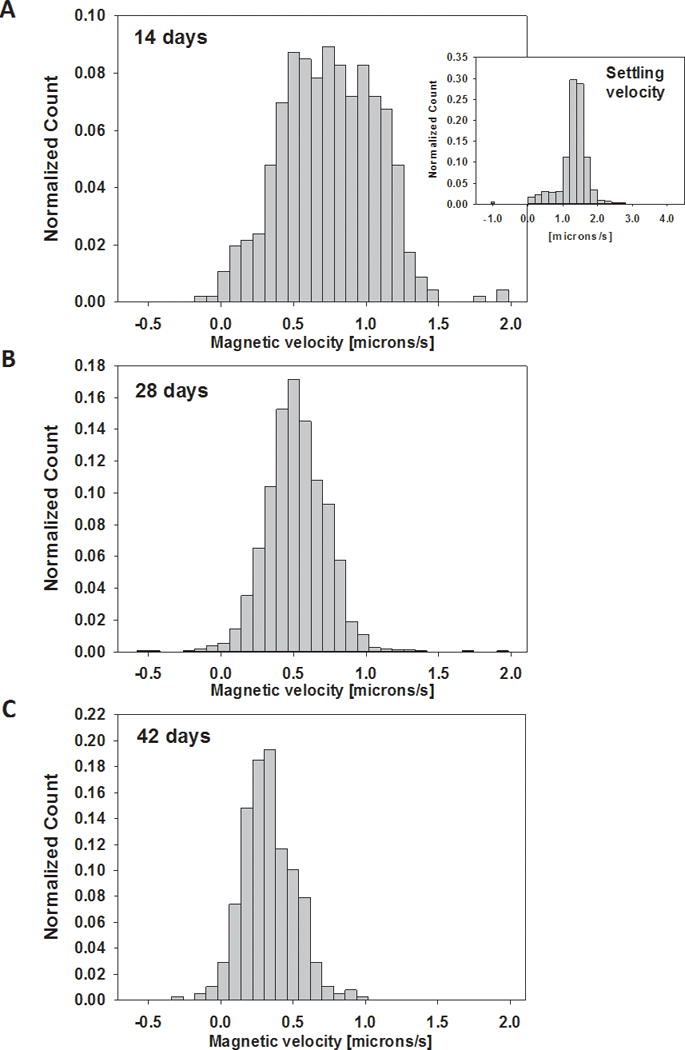

As indicated by Equation 4, dividing the experimentally measured magnetically induced velocity by the settling velocity for each tracked cell results in a non-dimensional velocity ratio, which is only a function of the cell’s magnetic susceptibility and density difference with the suspending fluid. Figure 3 presents plots of this velocity ratio as a function of storage time, for oxygenated, metHb, and deoxygenated RBCs, 3A, 3B, and 3C, respectively, for four different donors. Each bar is the mean of the RBCs tracked for the specific condition, and the error bars represent a 95% confidence interval. Visual inspection indicates a clear decrease in the ratio of um/us with storage for all three types of RBCs. As a point of comparison with respect to the size of the 95% confidence interval, one bar graphs are added from the data in Table 2 with a ratio of um/us in the same range of the RBCs.

Figure 3.

The ratio of RBC magnetic field induced velocity to settling velocity, um/us, of the four RBC samples at different storage times, for oxy, met, and deoxy forms of the Hb, 3A, 3B, and 3C, respectively. Error bars correspond to 95% confidence interval measurements. The dashed, horizontal lines in 3A, 3B, and 3C, correspond to the theoretical ratio of um/us for oxygenated, metHb, and deoxygenated RBCs.

The dashed lines in Figure 3 correspond to the theoretical ratio of um/us for oxygenated (Figure 3A), metHb (3B), and deoxygenated RBCs (3C).34 As can be observed, oxygenated RBCs approach the theoretical value of the ratio of um/us as the cells age during ex vivo storage. This is expected as it has been previously reported that the O2 saturation equilibrium of RBCs shifts to higher O2 affinity with time, and spectroscopic analysis of the actual samples used in Figure 3A indicated that the percent saturation increased from 90 to 100% from day 7 to day 42.34 In contrast, the metHb and deoxygenated RBCs exhibited the opposite behavior; RBCs approached the theoretical maximum ratio of um/us when the cells were fresh and decreased with ex vivo storage time. While one could explain that it is harder to deoxygenate the Hb contained in the RBCs with longer storage time, hence the lowering of the um/us ratio with time, this argument cannot be made with the metHb form. As with the oxygenated RBCs, spectroscopic analysis was conducted on the metHb-converted RBCs, and for all storage time points, 100% of the Hb was in the metHb state. This 100% metHb is to be expected with the chemical treatment used.41

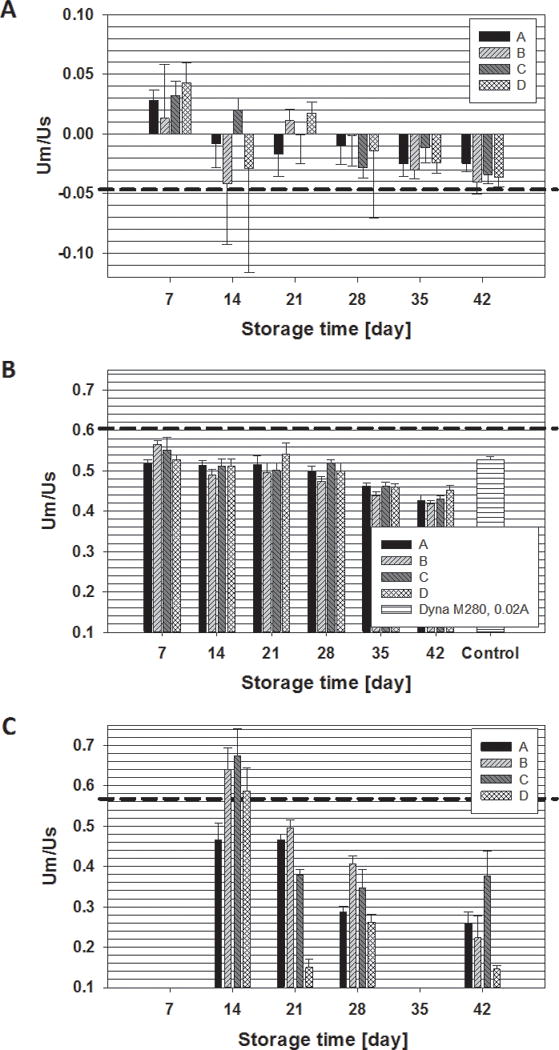

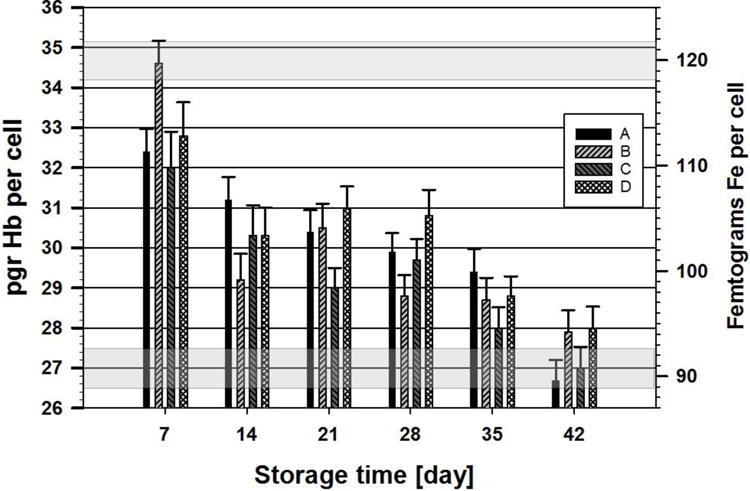

In Jin et al., we observed no change in RBC density, using Percoll gradient, for four different donors, measured on day 7, 14, 21, 28, and 35. The only slight drop was from the average of 1.10 g/ml, (1,100 kg/m3), for all of the samples, to 1.095 g/ml, on day 42 (p>0.05). Given the average density difference between the cell and suspending buffer, ∆ρ, the value of g/Sm, and χf are constant, the magnetic susceptibility of each individual RBC is directly proportional to the ratio of induced velocities, um/us. Therefore, Equation 6 allows one to calculate the concentration of Hb in mol/L, or the total amount of Hb in the cell (Equation 7). Figure 4 is a refinement of Figure 3B, with the y-axis on the left hand side, replaced with the amount of Hb per cell, in picograms (pg), and the y-axis on the RHS representing the number of femtograms (fg) of Fe atoms per cell (assuming all of the Fe is contained in the Hb). Table 3 presents this data with the percent change in Hb content between 7 and 42 days for each of the four donor samples.

Figure 4.

Mean values of the calculated concentration of Hb per cell (pg/cell) (LHS y-axis) and the corresponding number of Fe per cell (fg/cell) (RHS y-axis) for metHb as a function of storage time. As with previous plots, the 95% confidence interval is represented by error bars. The horizontal gray shaded areas correspond to the range of + 95% confidence around the specific mean value (i.e. for day 7, mean of 34.5 pgr Hb, range 34.2–35.2)

Table 3.

Amount of Hb (pg) per cell for metHb samples

| Sample | 7 day | 42 day | drop in Hb (%) | P values | # of Hb molecules lost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 33 + 11 | 27 + 9.3 | 5.7 (17%) | < 0.001 | 5.33 × 107 |

| B | 35 + 10 | 28 + 10 | 6.7 (19%) | < 0.001 | 6.26 × 107 |

| C | 32 + 16 | 27 + 9.9 | 5.1 (16%) | < 0.001 | 4.77 × 107 |

| D | 33 + 15 | 28 + 9.8 | 4.4 (14%) | < 0.001 | 4.11 × 107 |

|

| |||||

| Average | 33.0 | 27.6 | 5.4 (17%) | ||

As in the previous figures, the error bars represent a 95% confidence interval for the specific data set. The two gray boxes (or zones) in Figure 4, correspond to a range of approximately 5 fg, the suggested accuracy based on 95% confidence intervals. Visual inspection of Figure 4 indicates that the CTV instrument provides data demonstrating that not only there is a statistically significant drop in the amount of Hb (or Fe) as a function of storage, but also there can be statistical differences in different donor populations at a given time point.

It is clear from Figure 3C that the change in the um/us ratio with storage time is even greater in the deoxygentated cells than in the metHb cells (Figure 3B). Since, as discussed above for the oxygenated RBCs (Figure 3A), it is highly likely that not all of the RBCs are fully deoxygenated at these later time points. This would result in the RBCs having a lower um/us ratio (i.e., lower magnetic susceptibility), thereby exaggerating this decrease in Hb compared to that in the metHb-containing RBCs.

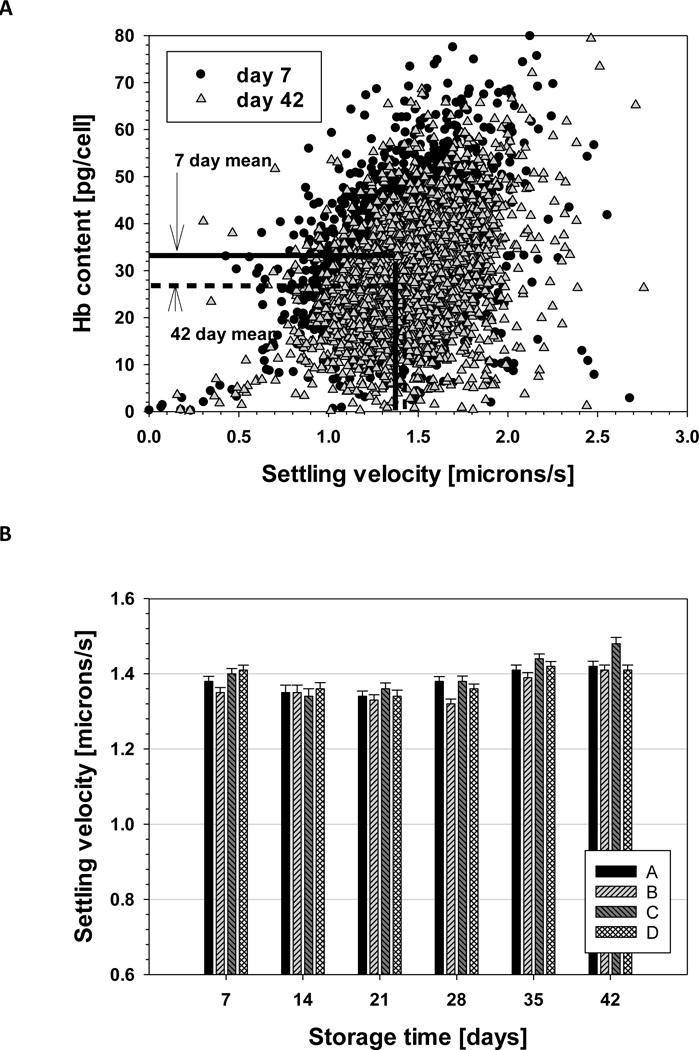

Potential variation of cell size with Hb content and storage

While the ratio of experimentally determined velocities, and the subsequent calculations, are independent of cell size (the drag term is the same for settling and magnetic velocity and subsequently cancelled in Equation 4), we further investigated if any correlation existed between the calculated Hb content and settling velocity (cell size), as well as any change in settling velocity (cell size) with the length of storage. Figure 5A presents the calculated Hb concentration per RBC versus settling velocity for all the cells from the four donors (n>4,000) at 7 and 42 days of storage in which the Hb was converted to the metHb form. The solid and dotted line corresponds to the mean of the Hb content and settling velocity, for the 7 and 42 day old samples, respectively. To further investigate the difference in settling velocity, and corresponding size of RBC with storage (since it was established that there is no significant difference in cell density), the mean and 95% confidence interval for the four donors at the six different time points are presented in Figure 5B. While slight changes are observable, it is not clear at this point what these changes mean.

Figure 5.

A) Calculated concentration of Hb per cell (pg/cell) as a function of settling velocity for each of the four donor populations at 7 and 42 days. B) the mean and 95% confidence interval for the settling velocity of RBC from each donor at six time points.

Conclusions

We suggest there are two significant findings in this study: (1) the CTV system can detect the difference in Hb concentration in two RBC populations to a resolution of 1 × 107 Hb molecules per cell (4 – 5 fg of Fe); (2) RBCs lose, on average, 16% of their Hb at 42 days of storage compared to the values at 7 days. The claim of this level of sensitivity is based on the ranges of the confidence interval presented in Figure 4 and the definition of confidence interval (i.e. the lack of overlap in confidence intervals provides a plausible conclusion that there is a difference in the average amount of Hb (Fe) in the specific populations).

We know of no other instruments with this level of sensitivity. The most common method to obtaining Fe concentration data, including the data in Table 3, uses state of the art Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). To obtain a sufficient amount of Fe signal above background with ICP-MS, cells on the order of 105 – 106 are needed to accurately quantify Fe content. Consequently, the concentration of Fe per cell is averaged over 1 × 106 cells. In contrast, using the CTV instrument, we are calculating the Fe content on a per-cell basis; therefore, it is 105 to 106 times more sensitive and effective compared to ICP-MS.

Further, we know of no other report indicating that stored RBCs lose the amount of Hb that we report here. It is important to note that we are basing this quantity of Hb lost on a per intact cell basis, not on measuring the amount of free Hb. Traditionally, the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) criteria for approving new RBC additive solutions is that at the proposed end of storage, no more than 1% free Hb must be present in the unit. This is a crude measurement of Hb loss and expressed as a percent of the total amount of Hb present in the unit. Given that it has been reported that sub-micron microvesicles are shed by stored RBCs, it is possible that at least some of this lost Hb are in these microvesicles.42

We suggest that the primary assumption that can be debated in this analysis is the assumption of RBC shape change during storage. While the determination of the ratio of the magnetic to settling velocity does not require knowledge of the hydrodynamic drag coefficient (which is a function of shape of the cell), converting the subsequently calculated magnetic susceptibility of the individual cell into a concentration of Hb within the cell does require the knowledge of the cell volume. A recent publication documents that over a 42 day storage period, RBCs change from 76/24 of disc/spherical split to a 23/77 disc/spherical distribution.43 Consequently, we reported our size estimates in terms of settling velocity in Figure 5, and not actual RBC size/volume. We suggest that future studies will also include a number of methods to investigate the cell size/volume with storage as a means to further refine the calculations of cell size/volume from settling velocity measurements.

While this study has focused on RBCs, we suggest that this experimental and analysis technique has applications beyond RBCs and can be used on any cell or particle that can be tracked with the CTV system. Further, as we have previously published, this system can be used to determine the diamagnetic properties of particles when the particles are suspended in paramagnetic fluids.37 In such a case, the repulsive magnetic force, in contrast to the attractive magnetic force, is determined. Otherwise, the mathematic analysis is identical. Also, the system is capable of measuring magnetic susceptibility of the continuous phase (including colloidal suspensions of nanoparticles) by tracking the magnetophoresis of tracer microspheres of known size and magnetic susceptibility (such as monodisperse polystyrene microspheres). Finally, we are developing systems in which the magnetic energy gradient, Sm, is approximately 10 times higher in the FOV of the instrument. Given the linear nature of the magnetically induced velocity with Sm (Equation 1), this corresponds to a 10-fold increase in instrument sensitivity. As indicated in Table 1, the average Fe concentration in cultured animal cells is on the order of 4 × 107 atoms per cell; a 10-fold increase in our analysis system indicates that not only can physiologically relevant Fe concentration measurements be made, but the instrument is sensitive enough to measure levels below this average level, which presents the potential to conduct studies when Fe concentrations are modulated.4

This work has some potentially important clinical implications. An allogeneic RBC unit from the blood bank contains RBCs of a variety of different ages – from reticulocytes that have just been released from the bone marrow through to RBCs that are nearing the end of their typical 120 day lifespan. This is important because it is known that the 24 hour RBC recovery (or survival after transfusion into a recipient) from units that have been stored for on average 5 days and would generally be considered “fresh” is only approximately 87%, while the recovery from RBC units that have been stored for a mean of 30 days is significantly lower at approximately 74% (p<0.01).44 This means that between 13 – 26% of the transfused RBCs are immediately cleared from the recipient’s circulation by the reticuloendothelial system (RES). This targeted delivery of Fe to the macrophages in the form of senescent RBCs is hypothesized to lead to an increase in non-transferrin bound Fe which might predispose the recipient to infection and oxidative complications, as well as the release of inflammatory cytokines that might cause or exacerbate lung injury following transfusion.45 Thus, if it would be possible to quickly, and in a sterile manner, use magnetic sorting to remove the oldest RBCs (i.e., those that have lost the most Hb) before the RBC unit was issued, the product provided to the recipient could be more potent in terms of its ability to transport O2 and the burden of senescent RBCs on the recipient’s RES would be reduced. Given the large quantity of RBCs that do not survive the first 24 hours post-transfusion in both fresh and older stored RBC units, magnetic sorting could be beneficial if applied to all RBC units issued by the blood bank. Administering fewer RBCs by eliminating those that had lost Fe during storage could also reduce adverse transfusion-related events such as circulatory (volume) overload and Fe overload in chronically transfused recipients such as those with sickle cell disease or chronic hematological malignancies, in addition to the benefits of reducing the Fe burden on the RES. We have demonstrated, as a proof of concept, the separation of deoxyHb and metHb RBCs from a cell mixture, and theoretical designs indicate that larger scale RBC separation based on intrinsic magnetization is possible.46

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.J. Chalmers and M. Zborowski thank the National Cancer Institute, (RO1 CA62349) and National Heart Lung Blood Institute (1R01HL131720-01A1), and J.J. Chalmers, M. Zborowski, and M. Yazer thank DARPA

References

- 1.Ganz T. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:1721–1741. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jutz G, Rijn P, Miranda S, Boker A. Chem Rev. 2015;115:1653–1701. doi: 10.1021/cr400011b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews SC, Robinson AK, Rodriguez-Quinones F. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:215–237. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pourcelot E, Lenon M, Mobilia N, Cahn JY, Arnaud J, Fanchon E, Moulis J, Mossuz P. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1853:1596–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutak R, Botebol H, Blaiseau PL, Léger T, Bouget FY, Camadro JM, Lesuisse E. Plant Physiol. 2012;160:2271–2284. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.204156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zborowski M, Ostera GR, Moore LR, Milliron S, Chalmers JJ, Schechter AN. Biophys J. 2003;84:2638–45. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75069-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pauling L, Coryell CD. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1936;22:210–216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.22.4.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pauling L, Coryell CD. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1936;22:159–163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.22.3.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seifried E, Klueter H, Weidmann C, Staudenmaier T, Schrezenmeier H, Henschler R. Vox Sang. 2011;100:10–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2010.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenburg AG. World J Surg. 1996;20:1189–1193. doi: 10.1007/s002689900181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greening DW, Glenister KM, Sparrow RL, Simpson RJ. J Proteomics. 2010;73:386–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott MG, Kucik DF, Goodnough LT, Monk TG. Clin Chem. 1997;43:1724–1731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Circular of Information: For the use of human blood and blood components. American Red Cross, America’s Blood Centers, Armed Services Blood Program. 2013 Copies available at: www.aabb.org/marketplace.

- 14.Tinmouth A, Chin-Yee I. Transfus Med Rev. 2001;15:91–107. doi: 10.1053/tmrv.2001.22613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vandromme MJ, McGwin G, Weinberg JA, Scand J. Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:35. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-17-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimrin A, Hess J. Vox Sang. 2009;96:93–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2008.01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koch CG, Figueroa PI, Li L, Sabik JF, Mihaljevic T, Blackstone EH. Ann Thor Surg. 2013;96:1894–1899. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zubair AC. Am J Hemo. 2010;85:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- 19.van de Watering L. Vox Sang. 2011;100:36–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2010.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rawn J. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2011;21:664–8. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32830f1fd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vamvakas EC. Transfus Med Rev. 1966;10:44–61. doi: 10.1016/s0887-7963(96)80122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vamvakas EC, Taswell HF. Transfusion. 1994;34:464–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1994.34694295059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creteur J, Vincent JL. Crit Care Clinics. 2009;25:311–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hess JR, Greenwalt TG. Transf Med Rev. 2002;16:283–295. doi: 10.1053/tmrv.2002.35212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott KL, Lecak J, Acker JP. Transf Med Rev. 2005;19:127–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanias T, Acker JP. FEBS J. 2010;277:343–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hess JR. J Proteomics. 2010;73:368–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hess JR. Transfus Apher Sci. 2010;43:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolfe LC. Transfusion. 1985;25:185–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1985.25385219897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Card RT. Transfus Med Rev. 1988:40–47. doi: 10.1016/s0887-7963(88)70030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fergusson DA, Hebert P, Hogan DL, LeBel L, Rouvinez-Bouali N, Smyth JA. JAM A. 2012;308:1443–1451. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lacroix J, Hebert PC, Fergusson DA, Tinmouth A, Cook DJ, Marshall JC. NEJ M. 2015;372:1410–1418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steiner ME, Ness PM, Assmann SF, Triulzi DJ, Sloan SR, Delaney M. NEJ M. 2015;372:1419–1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin X, Yazer MH, Chalmers JJ, Zborowski M. Analyst. 2011;136:2996–3003. doi: 10.1039/c0an01018a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura N, Lasky L, Zborowski M, Chalmers JJ. Exp Fluids. 2001;30:371–380. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang H, Zborowski M, Williams PS, Chalmers J. J Analyst. 2005;130:514–527. doi: 10.1039/b412723d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin X, Zhao Y, Richardson A, Moore L, Williams S, Zborowski M, Chalmers JJ. Analyst. 2008;133:1767–1775. doi: 10.1039/b802113a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jie X, Mahajan K, Xue W, Winter JO, Zborowski M, Chalmers JJ. JMMM. 2012;324:4189–4199. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2012.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chalmers JJ, Haam S, Zhao Y, McCloskey K, Moore L, Zborowski M. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;64:519–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore LR, Sun LP, Zborowski M, Nakamura M, Chalmers JJ, McCloskey K, Gura S, Burdygin I, Margel S. J Biochem Bioph Methods. 2000;44:115–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-022x(00)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winterbourn CC. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:265–272. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86118-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burger P, Kostova E, Bloem E, Hilarius-Stokman P, Meijer AB, van den Berg TK. Br J Haematol. 2013;160:377–386. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blasi B, Alessandro AD, Ramundo N, Zolla L. Transfusion Med. 2012;22:90–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2012.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luten M, Roerdinkholder-Stoelwinder B, Schaap NP, de Grip WJ, Bos HJ, Bosman GJ. Transfusion. 2008;48:1478–1485. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hod EA, Zhang N, Sokol SA, Wojczyk BS, Francis RO, Ansaldi D, Francis KP, Della-Latta P, Whittier S, Sheth S, Hendrickson JE, Zimring JC, Brittenham GM, Spitalnik SL. Blood. 2010;115:4284–4292. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-245001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moore L, Williams PS, Nehl F, Abe K, Chalmers JJ, Zborowski M. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014;406:1661–1670. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-7394-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.