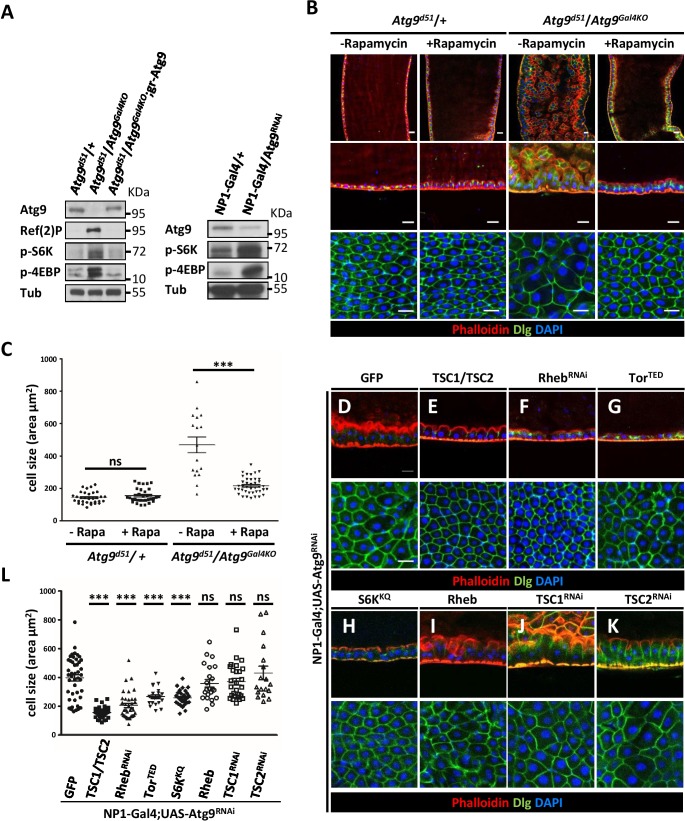

Figure 6. Loss of Atg9 enhances TOR activity in Drosophila adult midgut.

(A) The adult midguts of denoted genotypes were dissected, lysed, and subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-Atg9, anti-Ref(2)P, anti-p-S6K, anti-p-4EBP and anti-tubulin antibodies. (B) Inhibition of TOR activity by feeding flies with rapamycin rescued Atg9 mutant midgut defects. (C) Quantification of posterior midgut cell size shown in (B). n ≥ 17, data are mean ±s.e.m. ***p<0.001. (D–K) Atg9 genetically interacts with components of the TOR signaling pathway. The Atg9RNAi-induced midgut defects (D) could be suppressed by the coexpression of TSC1-TSC2 (E), RhebRNAi (F), dominant-negative TOR (TORTED) (G), or dominant-negative S6K (S6KKQ) (H), whereas coexpression of TOR activator Rheb (I) or knock-down of TSC1 (J) or TSC2 (K) could not rescue the Atg9RNAi-induced midgut defects. Genetic analyses were performed for three times with 100% penetrance of the phenotype. (L) Quantification of posterior midgut cell size shown in (D–K). n ≥ 18, data are mean ±s.e.m. ***p<0.001. ns, not statistically significant. Scale bar: 20 μm.