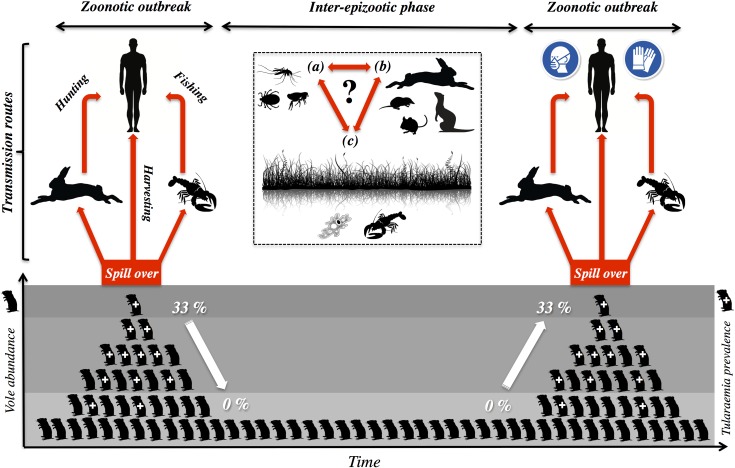

Fig 1. Dynamics of tularemia outbreaks in Northwest Spain.

Common voles (Microtus arvalis) are key agents for this disease in Northwest Spain (Castilla-y-León region), where outbreaks of tularemia among humans have been endemic in farming landscapes since 1997 (>1,300 cases in 1997–2016). Voles have been identified as a main spillover and amplification agent of tularemia because epizootic and epidemic episodes coincide in time and space with vole outbreaks. When the rodents reach peak densities (>1,000 voles/ha), up to 33% of them are infected with tularemia. Therefore, as vole numbers increase, so does the bacterium in the environment. Transmission routes of tularemia to humans during zoonotic outbreaks include (i) direct contact with wildlife species such as hares or crayfish, which coexist with voles in the same habitats, and (ii) trough inhalation during the harvesting of vole-infested crop fields. At low vole densities, the bacterium is not found among the rodents, indicating that, between vole outbreaks, populations of F. tularensis subs. holarctica may remain at lower numbers, associated with some yet-unknown reservoirs. Enzootic cycles in local wildlife other than voles, including hematophagous arthropods (a) and other small- and medium-sized mammals, (b) may also contribute to sustaining the bacteria in the environment during inter-epizootic periods. Water is a main habitat for reservoir candidates (c) because it is a well-known favorable habitat for tularemia (most especially in these semiarid landscapes of Northwest Spain).