Abstract

Twenty-first birthdays are associated with heavier drinking and more negative consequences than any other high-risk drinking event. Friends are the strongest social influence on young adult drinking; however, previous research on college students’ drinking has often only examined individuals’ perceptions of “friends” generally. Unfortunately, this may obscure the positive influence of some friends and the negative influence of others. Using data drawn from a larger intervention study aimed at reducing 21st birthday drinking, this research examined how specific friends (N=166) who were present at 21st birthday celebrations may have exacerbated or mitigated celebrants’ (N=166) experience of alcohol-related consequences, as well as how characteristics of that friendship moderate these effects. Controlling for sex, alcohol consumption, and friend pro-intoxication intentions for the celebrants’ 21st birthday drinking, higher friend pro-safety/support intentions predicted the celebrants experiencing fewer alcohol-related consequences. Higher pro-safety/support intentions also buffered participants from the negative influence of friend pro-intoxication intentions. Further, the closeness of the friendship moderated this effect. At high levels of closeness, having a friend with lower pro-safety/support intentions was associated with more alcohol-related consequences for the celebrant. Post-hoc analyses revealed that this effect may have been driven by discrepancies between celebrants’ and friends’ reports of friendship closeness; celebrants’ perception of closeness that was higher than the friends’ perception was associated with the celebrant experiencing more alcohol-related consequences. Results demonstrate the ways that specific friends can both mitigate and exacerbate 21st birthday alcohol-related consequences. The implications of the present findings for incorporating specific friends into drinking-related interventions are discussed.

Keywords: alcohol, event-specific prevention, social context, close relationships, college students

Turning 21 is associated with particularly heavy drinking and experiencing negative alcohol-related consequences. Approximately 80 to 90% of college students drink when celebrating their 21st birthday (Neighbors et al., 2011; Rutledge, Park, & Sher, 2008), with the average celebrant consuming approximately eight drinks during the celebration (Day-Cameron, Muse, Hauenstein, Simmons, & Correia, 2009). Half of 21st birthday drinkers drink more on their 21st birthday than on any previous occasion (Rutledge et al., 2008). Almost 70% of students drink more than they intend while celebrating their 21st birthday (Brister Wetherill, & Fromme 2010). The 21st birthday ranks higher than other events or holidays in terms of proportion of college students who drink and the blood alcohol concentrations they reach (Neighbors et al., 2011). Drinking on 21st birthdays is associated with a high proportion of related consequences ranging in severity, some of which can be extremely harmful to college students, including police involvement, property damage, physical or sexual assault, unsafe sex, health problems, and drunk driving, among others (White & Hingson, 2014). Compared to typical drinking, 21st birthday celebrants report increased rates of consequences, particularly if they do not typically drink excessively (Lewis, Lindgren, Fossos, Neighbors, & Oster‐Aaland, 2009). Further, a recent study indicates that higher levels of alcohol use on one’s 21st birthday is predictive of increased peak consumption and alcohol-related consequences after the celebration, and these effects were strongest among students who reported lower peak drinks prior to their 21st birthday (Geisner et al., 2017). Identifying and understanding factors associated with heightened risk for experiencing negative consequences as a result of 21st birthday drinking is integral for designing prevention efforts to address problematic drinking during this particularly high risk event.

Friend Influences on Drinking

The majority of college students drink in social contexts and for social reasons (e.g., Beck, Caldeira, Vincent, & Arria, 2013; Fairbaim & Sayette, 2014; Grant, Stewart, O’Connor, Blackwell, & Condrod, 2007). In fact, friends are the strongest source of social influences on young adult drinking (Lewis, Neighbors, Lindgren, Buckingham, & Hoang, 2010; Neighbors et al., 2010). Although extensive research has demonstrated social influences to be among the strongest factors associated with drinking in college students (e.g., Fairbaim & Sayette, 2014; Lewis et al., 2010; Neighbors et al., 2010), these social influences can vary along multiple dimensions including specificity (e.g., other people in general vs. one particular person), importance (i.e., some people may be viewed as more important than others), and level of directness (e.g., cognitions about society’s approval of alcohol vs. being given an unsolicited drink by a friend; Borsari & Carey, 2001; Graham et al., 1991).

The ever-present importance and influence of friends can be understood through the framework of interdependence theory (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Kelley et al., 2003). Two individuals are said to be interdependent when one person’s emotion, cognition, or behavior affects the cognition, emotion, and/or behavior of the other person. Interdependence theory highlights the importance of adopting a dyadic perspective to understand how two individuals’ behaviors likely affect each other and their established relationship. The pattern of interdependence represents the abilities and desires each person brings to the friendship as well as the way in which these two sets of personal dispositions interact and engage with one another to form and maintain a friendship.

Unfortunately, prior work examining the influence of friends on college students’ drinking has important limitations. Previous research has often examined participants’ perceptions of friends generically or abstractly (e.g., general social group, close friend; Baer et al., 1991; Chawla et al., 2009; Martens et al., 2006; Real & Rimal, 2007), but there are problems with this approach. First, it is unclear whether this approach captures the influence of actual friends or just potentially biased perceptions of friends. Understanding the actual influence of friends requires data collected directly from the friends, preferably from individuals present at specific drinking events. Doing so would allow for a truly dyadic examination of celebrants and their friends in drinking contexts. Second, the approach used in prior research obscures any differentiation between some friends’ helpful or protective influence, and other friends’ harmful or negative influence. Both of these limitations are addressed in the current research.

Like all individuals, friends carry with them specific beliefs about 21st birthdays, as well as intentions for the individuals who are celebrating their 21st birthdays. These beliefs are likely informed by their own experiences, normative perceptions, and baseline drinking levels. Although this has not yet been examined in the literature, we believe that friends’ intentions to exacerbate drinking (termed “pro-intoxication intentions”), as well as their intentions to protect and support the celebrant (termed “pro-safety/support intentions”) during their 21st birthday celebration, will influence the number of alcohol-related consequences the celebrant will experience. Thus, this research seeks to identify characteristics of specific friends and characteristics of the relationship with those friends, as well as how these characteristics mitigate or exacerbate risk on celebrants’ 21st birthdays.

Features of the Relationship – Closeness

Among all potential friends, those with whom the celebrant shares strong bonds are likely to be more influential on their drinking behavior. Closeness is considered a multidimensional construct comprising time spent together, variety of activities engaged in together, and the extent of perceived influence that the other person has on one’s actions, activities, and plans (Berscheid, Snyder, & Omoto, 1989). Thus, beliefs and intentions of close friends likely have a greater influence on celebrants’ drinking and experience of alcohol-related consequences. In this study, closeness was operationalized by participants’ choosing among seven sets of overlapping circles wherein they overlap with their friend, from not overlapping at all to almost completely overlapping. Closer friends are perceived as having greater overlap, thus representing greater intimacy, similarity, and self-disclosure within the friendship (Aron, Aron, & Smollan, 1992). We expect that the influence of friends’ intentions will be stronger for friends who are closer to the celebrant compared with friends who are not as close.

The Present Research

Past work examining the influence of friends on drinking and related consequences is limited in that researchers have often relied on individuals’ perceptions of their friends’ drinking attitudes and behavior, as opposed to assessing actual friends’ self-reports. Unfortunately, these studies are unable to determine whether any effects truly reflect friends’ influence or simply the effects of individuals’ perceptions of those friends. The present research addresses these limitations by assessing the intentions of specific friends who were present during a particularly high-risk drinking event, 21st birthday celebrations. This increased level of specificity allows us to directly examine factors relevant to friends and celebrants during a specific event, and thus will provide insight into the novel question of when friends may have beneficial versus iatrogenic influence on drinking and related consequences.

Brief interventions have been developed to address heavy drinking among college students, with the most successful involving personalized feedback (see Dotson, Dunn, & Bowers, 2015 and Scott-Sheldon, Carey, Elliott, Garey, & Carey, 2014 for meta-analyses). While the results of these interventions have been encouraging, reduction in the average number of drinks a person consumes per week or on a typical occasion does not address the often dangerous drinking that occurs during specific events associated with high-risk drinking (e.g., Geisner et al., 2017; Neighbors et al., 2011). The present research draws upon data from an intervention study designed to evaluate an event-specific indicated prevention (ESP) paradigm by adapting existing empirically-supported college student alcohol interventions to address specific high-risk events (see Neighbors et al., 2012). This study also evaluated friends’ involvement in ESP by incorporating friends into the intervention efforts. While the findings of the study suggest ESP is efficacious for high-risk drinking associated with these events, the evidence for the use of friends as intervention agents was less clear (Neighbors et al., 2012). Whereas friends were incorporated to help reduce the celebrant’s drinking and related consequences in two of five conditions, both intervention studies found null effects for the addition of friends to the interventions (despite overall support for ESP).

Preliminary results suggest that these null effects are not due to a total lack of friend influence, but rather that some friends may be helpful, while others encourage the very effects the intervention attempted to minimize. The present research involves secondary data analyses designed to examine this possibility, with a particular focus on (1) the pro-intoxication and pro-safety/support intentions reported by the specific friends before the birthday celebration, and (2) the closeness of the relationship between the celebrant and the friend. The focal aims include:

Aim 1

Examine how a specific friend present at the 21st birthday celebration may mitigate or exacerbate the celebrant’s experience of alcohol-related consequences.

Hypothesis 1

Friend pro-intoxication intentions should predict the celebrant experiencing more alcohol-related consequences during their 21st birthday week.

Hypothesis 2

Friend pro-safety/support intentions should predict the celebrant experiencing fewer alcohol-related consequences during their 21st birthday week.

Aim 2

Examine the moderating role of relationship closeness with the specific friend.

Hypothesis 3

The closeness of the friendship should moderate the effects of friend pro-intoxication and pro-safety/support intentions. That is, pro-intoxication intentions of a closer friend should be stronger predictors of the celebrant experiencing more alcohol-related consequences than those of a less close friend. Pro-safety/support intentions of a closer friend should be stronger predictors of the celebrant experiencing fewer alcohol-related consequences than a less close friend.

Method

Participants

Data for the present research were drawn from a larger intervention study aimed at reducing 21st birthday drinking (see Neighbors et al., 2012). Participants included 166 (45.8% male) individuals celebrating their 21st birthdays and 166 (48.2% male) of their friends who were present at the birthday celebration. Celebrants turned 21 during their participation in the study and their friends were, on average, 20.8 years old (SD = 1.70 years). Celebrant race included 67.5% Caucasian, 15.7% Asian, 8.4% Multi-ethnic, 4.8% Other, 1.8% African American, and 1.8% Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander. Five percent of celebrants identified as Hispanic/Latino.

Procedure

Individuals about to turn 21 were eligible to participate in the study if they: (a) intended to consume four (for women) or five (for men) drinks during their 21st birthday; (b) listed the email address of at least one friend, 18 years or older, with whom they planned to celebrate their birthday; and (c) had not previously participated in the study as a friend of another celebrant. Individuals who participated in the two friend intervention conditions, 21 BASICS + friend intervention and 21 WEB BASICS + friend intervention, were included in analyses. See Neighbors et al. (2012) for a more detailed description of the intervention conditions.

College students about to turn 21 completed an initial screening survey three weeks prior to their 21st birthday. Eligible participants were invited to immediately complete an initial survey. During the initial survey, celebrants listed up to three friends who they planned to be with during their birthday celebration and reported their closeness to each friend. These friends were invited via email to participate in the study. For the 213 eligible participants randomized to the friend intervention conditions, 201 completed the baseline survey, 383 friends were invited to participate, and 283 of those friends consented to participate. Two days prior to the celebrant’s birthday, consenting friends were emailed a link to complete the friend assessment, followed by the intervention. Of the 283 friends who consented to participate, 241 logged on to the online assessment (81.5%). During this assessment, friends’ reported their pro-intoxication and pro-safety/support intentions for the participant while celebrating their 21st birthdays. One week after the celebrant’s 21st birthday, celebrants and friends were emailed a follow-up survey. Celebrants reported the number of drinks they consumed on their 21st birthday celebration, the number of hours they consumed the drinks (which was used to calculate eBAC along with their birth sex and weight), and the number of alcohol-related consequences they experienced throughout their birthday week. Data from friends’ follow-up surveys were not used in the present analyses. The protocol was approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

Choosing friend for analyses

The pro-intoxication and pro-safety/support intentions of one friend identified by each celebrant were used in the present research. Only data from friends who were present during the 21st birthday celebration and completed pre- and post-birthday surveys were used. If more than one friend per participant met these criteria (n=19), the friend with the closer relationship type was chosen (e.g., “romantic partner” chosen over “friend,” “friend” chosen over “acquaintance”). If multiple friends met criteria and had the same type of relationship with the participant, the first individual listed by the participant was chosen. The final sample consisted of 166 friends. Most friends were classified as best friends (38.6%), but friends (30.7%) and romantic partners (22.9%) were also commonly chosen. The remaining chosen friends included relatives (6.6%), a co-worker/colleague (.6%), or an acquaintance (.6%).

Measures

Closeness of friend relationship

Celebrants and friends reported the closeness of their relationship with each other using the Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale (IOS; Aron, Aron, & Smollan, 1992). The IOS is a single-item measure of closeness consisting of seven pairs of overlapping circles (representing the self and the friend), which range from no overlap (0) to almost complete overlap (6). Higher scores indicate feeling closer to the other person. Participants (celebrants and friends) were instructed to “select the pair of circles that you feel best represents the closeness of your friendship.” Celebrants’ report of friendship closeness was used in the primary analyses.

Friend intentions

Friends reported their intentions for the participant while celebrating their 21st birthdays using 6 items created for the present research. Three items were combined to create a measure of friends’ pro-intoxication intentions (i.e., “I encourage [celebrant name]’s drinking”; “I will encourage [celebrant name]’s drinking while celebrating [his or her] 21st birthday” and; “I will encourage [celebrant name] getting drunk while celebrating his/her 21st birthday”; α = .87). Three items were combined to create a measure of friends’ pro-safety/support intentions (i.e., “I am supportive of [celebrant name] (i.e., sensitive to [his or her] personal needs, help [celebrant name] to think about things, etc.)”; “I am supportive of [celebrant name] staying safe while celebrating [his or her] 21st birthday”; “I would like to help [celebrant name] reduce negative alcohol-related consequences during [his or her] 21st birthday celebration”; α = .69). All items were rated on six-point Likert-type scales ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Scores were summed for each subscale, resulting in a possible range of 0 to 15 for each.

Alcohol consumption

The number of drinks consumed during each day of the week of celebrants’ 21st birthday (3 days before through 3 days after the birthday) was assessed using an adapted version of the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). For each day, celebrants were asked, “How many drinks did you consume?”, as well as “Over how many hours did you drink?” The total number of drinks celebrants reported consuming during these 7 days was used for the present research.

Alcohol-related consequences

Participants experience of alcohol-related consequences during their birthday week was assessed using 7 items taken from a modified version of the Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (YAAPST; Hurlbut & Sher, 1992) (see Neighbors et al., 2012). The measure assesses individuals’ experience of negative alcohol-related consequences such as “Did you feel very sick to your stomach or throw up after drinking?” and “Did you wake up the morning after a good bit of drinking and find that you could not remember a part of the evening before?” In the present research, questions were prefaced with, “During the week of your 21st birthday.” Items were summed to create a measure of the total number of alcohol-related consequences experienced during the birthday week.

Data Analytic Approach

Because the focal outcome (i.e., alcohol-related consequences) was a count variable, hypotheses were evaluated utilizing hierarchical negative binomial regression models (Hilbe, 2011). Compared to Poisson, zero-inflated Poisson, and zero-inflated negative binomial models, negative binomial estimation provided best model fit across values of alcohol consequences. Additionally, relative to these other types of models, the negative binomial model also demonstrated the lowest Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC = 711.56), with the second lowest being the zero-inflated negative binomial (BIC = 740.56). The first model examined the main effects of friend pro-intoxication intentions and friend pro-safety/support intentions. The second model additionally examined the main effect of the closeness of the relationship between the celebrant and the friend, as well as all possible two-way interactions among these variables (i.e., pro-intoxication intentions × pro-safety/support intentions, pro-intoxication intentions × closeness, pro-safety/support intentions × closeness). Both models also controlled for effects of celebrant birth sex and celebrant total alcohol consumption during the week of their 21st birthday1. We also examined a third model which included the three-way interaction among friend pro-intoxication intentions, friend pro-safety/support intentions, and relationship closeness. However, this interaction was not significant, so it was dropped from the model and is not reported. All continuous predictors were mean centered. Birth sex was contrast-coded (female = −.5, male = .5). In cases of significant interactions, follow-up tests examined simple slopes. In this case, simple slopes are represented by rate ratios because log-linked coefficients are exponentiated for interpretation. Rate ratios represent the proportion of change in the dependent variable for each unit increase in the predictor. For example, a rate ratio of 1.26 would represent a 26% increase in alcohol-related consequences, whereas a rate ratio of .76 represents a 24% decrease in alcohol-related consequences, for each one-unit increase in the predictor.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations for all celebrant study variables are presented in Table 1. Celebrant sex was significantly associated with birthday week alcohol consumption (r = .23); men consumed significantly more drinks than women did. Additionally, celebrant birthday week alcohol consumption was significantly associated with total number of negative alcohol-related consequences experienced during the birthday week (r = .45). The most commonly-reported consequences were having a hangover (61.4%), not remembering part of the evening and correlations for all friend study variables are presented in Table 2. Friend birth sex was marginally associated with pro-intoxication intentions (r = .15) and significantly associated with pro-safety/support intentions (r = −.38) and perceived closeness to the celebrant (r = −.18). Male friends had higher pro-intoxication intentions, lower pro-safety/support intentions, and reported feeling less close to the celebrant than did female friends. Additionally, friend pro-intoxication intentions were significantly negatively associated with friend helpful intentions (r = −.23) and perceived closeness to the celebrant (r = −.18). Friend pro-safety/support intentions were significantly associated with perceived closeness to the celebrant (r = .35).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations among celebrant study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | M (SD) or N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Birth sex (% male) | – | 166 (45.78) | ||

| 2. Total birthday week alcohol consumption | 0.23** | – | 19.48 (14.10) | |

| 3. Total birthday week alcohol-related consequences (YAAPST) | 0.02 | 0.45*** | – | 2.88 (3.67) |

| 4. Closeness to friend | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 4.59 (1.42) |

Notes. Celebrant birth sex was contrast coded: 0.5 = male, −0.5 = female; YAAPST = Young Adult Alcohol Screening Test.

p < .01.

p < .001

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations among friend study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | M (SD) or N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Friend birth sex (% male) | – | 166 (48.19) | ||

| 2. Pro-intoxication | 0.15† | – | 9.10 (3.32) | |

| 3. Pro-safety/support intentions | −0.38*** | −0.23** | – | 13.67 (1.62) |

| 4. Closeness to celebrant | −0.18* | −0.18* | 0.35*** | 4.68 (1.39) |

Notes. Friend birth sex was contrast coded: 0.5 = male, −0.5 = female

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Among the most striking findings from descriptive examination of variables was the distribution of pro-safety/support intentions relative to pro-intoxication intentions. Both variables had possible ranges from 0 to 15. Pro-intoxication scores were relatively normally distributed and covered the entire range of possible scores. In contrast, pro-safety/support scores exhibited a high degree of negative skew, and responses only ranged from 7 to 15. Further, nearly the full range of pro-intoxication intentions was represented at each value of pro-safety/support intentions. This has bearing on interpretation of any results for pro-safety/support intentions because most of the scores are near the top of the range, and there is relatively little variability associated with reporting high pro-safety/support intentions. Scores that stand out are those that are not at the very high end; thus, any effects associated with pro-safety/support intentions are likely to represent the influence of those with intentions that were less than completely supportive.

Aim 1: Examine how a specific friend present at the 21st birthday celebration may mitigate or exacerbate the celebrant’s experience of alcohol-related consequences

To investigate Aim 1, the main effects of friend pro-intoxication intentions and pro-safety/support intentions were included in the model. Results revealed a significant main effect of celebrant birth sex and a marginal main effect of celebrant total birthday week alcohol consumption (see Table 3). Friend pro-intoxication intentions did not predict celebrants’ experience of alcohol-related consequences (Hypothesis 1). However, in support of Hypothesis 2, greater friend pro-safety/support intentions predicted the celebrant’s experience of fewer alcohol-related consequences.

Table 3.

Celebrants’ experience of alcohol-related consequences during their 21st birthday week as a function of friends’ pro-intoxication and pro-safety/support intentions, moderated by relationship closeness

| Model 1 | b | Std. Err. | Z | P > |Z| | eb | L95% | H95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.882 | 0.073 | 12.06 | .000 | 2.416 | 0.739 | 1.026 |

| Celebrant Birth Sex | −0.370 | 0.158 | −2.34 | .019 | 0.691 | −0.680 | −0.061 |

| Celebrant Total Birthday Week Alcohol Consumption [c] | 0.040 | 0.006 | 6.88 | .000 | 1.041 | 0.029 | 0.052 |

| Friend Pro-Intoxication Intentions [c] | 0.025 | 0.023 | 1.06 | .287 | 1.025 | −0.021 | 0.070 |

| Friend Pro-Safety/Support Intentions [c] | −0.093 | 0.048 | −1.95 | .051 | 0.911 | −0.187 | 0.000 |

|

| |||||||

| Model 2 | b | Std. Err. | Z | P > |Z| | eb | L95% | H95% |

|

| |||||||

| Intercept | 0.858 | 0.074 | 11.53 | .000 | 2.358 | 0.712 | 1.003 |

| Celebrant Birth Sex | −0.431 | 0.155 | −2.79 | .000 | 0.650 | −0.734 | −0.129 |

| Celebrant Total Birthday Week Alcohol Consumption [c] | 0.038 | 0.005 | 7.01 | .000 | 1.039 | 0.028 | 0.049 |

| Friend Pro-Intoxication Intentions [c] | 0.021 | 0.023 | 0.90 | .367 | 1.021 | −0.024 | 0.066 |

| Friend Pro-Safety/Support Intentions [c] | −0.087 | 0.055 | −1.59 | .112 | 0.917 | −0.195 | 0.020 |

| Celebrant-Reported Closeness [c] | −0.048 | 0.048 | −1.01 | .310 | 0.953 | −0.141 | 0.045 |

| Pro-Intoxication * Pro-Safety/Support | −0.031 | 0.015 | −2.05 | .041 | 0.969 | −0.061 | −0.001 |

| Pro-Intoxication * Closeness | 0.005 | 0.015 | 0.35 | .727 | 1.005 | −0.024 | 0.035 |

| Pro-Safety/Support * Closeness | −0.082 | 0.031 | −2.65 | .008 | 0.921 | 0.712 | 1.003 |

Note. Celebrant birth sex was contrast coded: 0.5 = male, −0.5 = female. [c] denotes a centered variable.

Aim 2: Examine the moderating role of relationship closeness with the specific friend

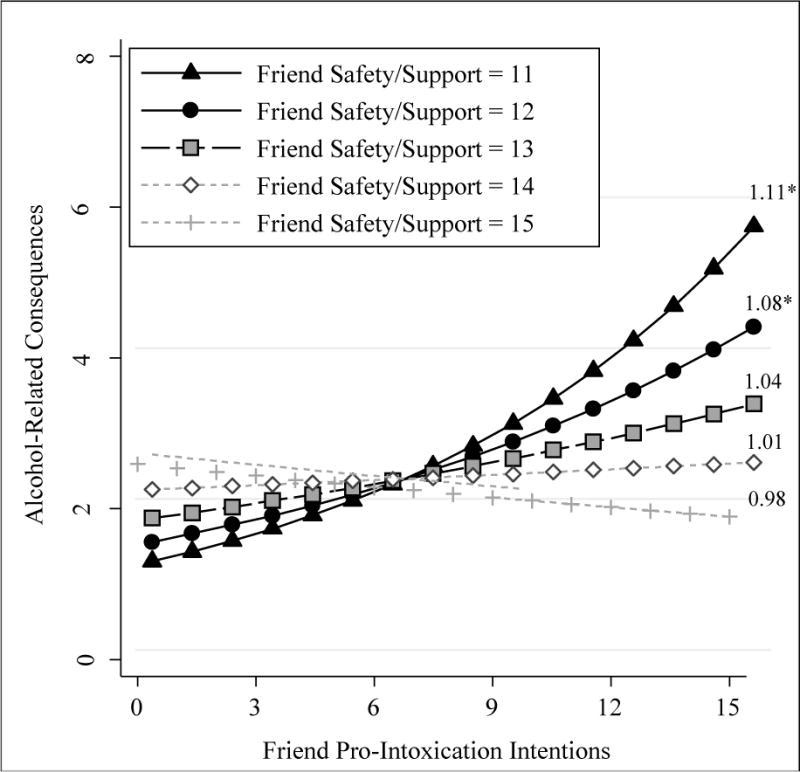

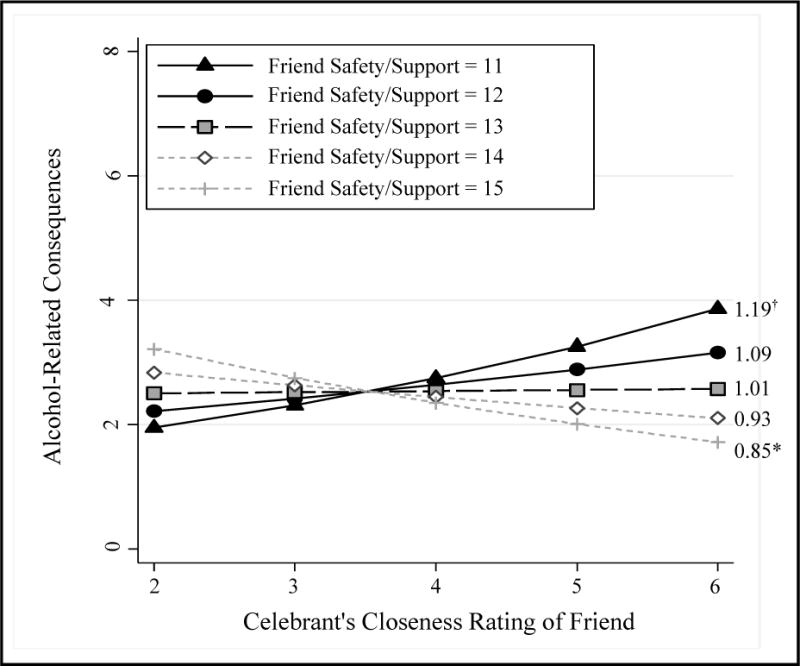

To investigate Aim 2, the main effect of relationship closeness, as well as all possible two-way interactions among pro-intoxication intentions, pro-safety/support intentions, and celebrant’s reported closeness to the friend were added to the model. The main effect of closeness was not associated with alcohol-related consequences. However, results revealed significant two-way interactions between friend pro-intoxication intentions and friend pro-safety/support intentions (see Figure 1), as well as between relationship closeness and friend pro-safety/support intentions (see Figure 2). Follow-up tests for the friend pro-intoxication intentions × pro-safety/support intentions interaction revealed that at lower levels of friend pro-safety/support intentions, celebrants’ experience of alcohol-related consequences increased by 11% with each one unit increase in friend pro-intoxication intentions. However, at higher levels of friend pro-safety/support intentions, celebrants’ experience of alcohol-related consequences were not related to friend pro-intoxication intentions. With respect to the interaction between closeness and friend pro-safety/support intentions (see Figure 2), at lower levels of friend pro-safety/support intentions, celebrants’ experience of alcohol-related consequences increased by 19% with each one unit increase in closeness to the friend. However, at higher-levels of friend pro-safety/support intentions, celebrants’ experience of alcohol-related consequences decreased by 15% with each one unit increase in closeness to the friend.

Figure 1.

Friend pro-intoxication intentions are associated with more alcohol-related consequences for the celebrant, unless friends also report very high pro-safety/support intentions.

Note. Numbers to the right of the graph represent rate ratios for each level of friend pro-safety/support intentions.

*p < .05.

Figure 2.

Having a closer friend with lower pro-safety/support intentions is associated with more alcohol-related consequences for the celebrant.

Note. Numbers to the right of the graph represent rate ratios for each level of friend pro-safety/support intentions.

†p < .10 * p <.05

Post-hoc Analyses

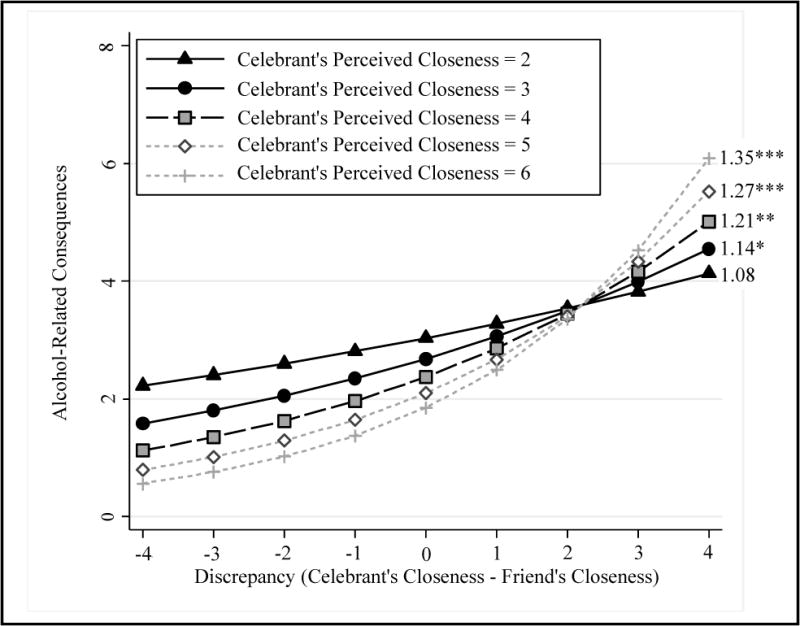

In support of Hypothesis 3, we found that the intentions of closer friends were stronger predictors of celebrants’ experience of alcohol-related consequences. We expected that higher pro-safety/support intentions among closer friends would be most beneficial, but were somewhat surprised by how detrimental lower pro-safety/support intentions were among closer friends. We conducted follow-up analyses to examine this finding further. We used celebrants’ report of closeness to the friend in the primary analyses; however, both celebrants and friends provided data on their perceived closeness with the other person. Therefore, we examined whether discrepancies between celebrants’ ratings of closeness with friends and friends’ ratings of closeness with celebrants might interact with friend intentions or closeness in predicting drinking-related consequences. We created discrepancy scores by subtracting the friends’ rating of closeness to the celebrant from the celebrant’s rating of closeness to the friend. Therefore, positive discrepancy scores indicate that the celebrant perceived greater closeness to the friend than did the friend. Results from a model where—in addition to previous predictors (i.e., celebrant birth sex, celebrant total birthday week alcohol consumption, friend pro-safety/support and pro-intoxication intentions, pro-safety/support × pro-intoxication interaction, pro-intoxication × closeness interaction, and the pro-safety/support × closeness interaction)—we also included two-way interactions with discrepancy and friend pro-safety/support and pro-intoxication intentions and perceived closeness indicated a significant discrepancy × closeness interaction, Z = 2.45, p = .014. As is presented in Figure 3, follow-up tests revealed that at higher levels of celebrant-perceived closeness, each one unit increase in discrepancy (celebrants perceiving greater closeness than friends perceive) is associated with celebrants experiencing 35% more alcohol-related consequences. However, discrepancy is unrelated to alcohol-related consequences at lower celebrant-perceived closeness.

Figure 3.

Among celebrants who perceived higher levels of closeness to their friend, believing they were closer to their friend than the friend reported was associated with greater alcohol-related consequences.

Note. Discrepancy scores were created by subtracting the friend’s rating of closeness to the celebrant from the celebrant’s rating of closeness to the friend. Therefore, positive discrepancy scores indicate that the celebrant perceived greater closeness to the friend than did the friend, and negative discrepancy scores indicate that the friend perceived greater closeness to the celebrant than did the celebrant. Numbers to the right of the graph represent rate ratios for each level of celebrant perceived closeness. * p < .05 **p < .01 ***p < .001

Discussion

The present research examined the positive and negative influence of specific friends on individuals’ experience of negative alcohol-related consequences during the week of their 21st birthday celebration, as well as the role of the closeness of the relationship with these friends in moderating these effects. It fills an important gap in the literature on the influence of friends on college student drinking by incorporating self-reports from specific friends who were present at a high-risk drinking event and considering features of the relationship with those specific friends. Results revealed that friends can exert both a helpful and harmful influence on the celebrant during this high-risk drinking event. The pro-safety/support intentions of friends were most influential, particularly when their relationship to the celebrant was closer.

The Importance of Supportive Friends

One of the primary contributions of the current study to the wider literature on hazardous drinking in high-risk events is revealing the particular importance of friends’ pro-safety/support intentions. Friends were able to mitigate the negative consequences of drinking, if they intended to be supportive of the celebrant and help them stay safe while celebrating their 21st birthday. Celebrants reported fewer alcohol-related consequences if their friends reported higher pro-safety/support intentions. These pro-safety/support intentions also helped buffer celebrants from the negative effects of friends’ pro-intoxication intentions. Celebrants whose friends had both high pro-safety/support intentions and high pro-intoxication intentions actually experienced fewer alcohol-related consequences than those whose friends had low pro-intoxication intentions, but also low pro-safety/support intentions.

Interestingly, these protective effects only occurred at the highest levels of pro-safety/support intentions. Thus, it is not simply the presence of helpful intentions that is responsible for reducing negative alcohol-related consequences in this high-risk context, but rather their absence that appears to be most harmful. Whereas friends’ pro-intoxication intentions for the celebrant were normally distributed – friends varied greatly in whether they intended to get the celebrant drunk – friends’ pro-safety/support intentions were negatively skewed. All friends in the present research reported at least moderate levels of pro-safety/support intentions (7 or greater on a range of 0 – 15). Thus, the effects of these intentions found in the present research are likely to represent the influence of friends with intentions that were less than completely supportive. When it comes to the effect of friends in the context of 21st birthday celebrations, it appears that anyone who is not completely with us is against us.

The Importance of Relationship Closeness

As predicted, the present research found that the intentions of close friends are stronger predictors of celebrants’ alcohol-related consequences. When the relationship with the friend was very close, higher pro-safety/support intentions were associated with the celebrant experiencing fewer alcohol-related consequences, and lower pro-safety/support intentions were associated with the celebrant experiencing more alcohol-related consequences. Once again, this finding reveals the dangers of having less than completely supportive friends present at one’s 21st birthday celebration. Post-hoc analyses revealed that the degree to which celebrants and friends agreed on their level of closeness was also an important predictor of alcohol-related consequences. Celebrants who perceived greater relationship closeness than did the friend experienced greater alcohol-related consequences, particularly at high levels of celebrant-perceived closeness. Thus, being wrong about who your close friends are appears to be particularly dangerous in this high-risk drinking context. This detrimental effect may be due to these friends not providing the level of support that the celebrant may have expected, given their perception of the relationship as particularly close.

This finding also highlights the importance of considering dyadic processes when examining the influence of close relationships in a drinking context. Solely focusing on the perceptions of one of the individuals (as does most research) neglects at least half of the picture and undermines the ability to understand the complex components of dynamic relationships (e.g., discrepancies in perceived closeness between both partners). Additionally, although it is important to consider that most drinking among college students occurs in a group context, our findings demonstrate that specific features of an individuals’ relationships with specific members of those groups (i.e., closeness) can play an important role in shaping the ways in which members of the group influence each other. Therefore, research on this topic would benefit from considering factors at the individual, dyadic, and group levels.

Strengths and Limitations

The current research has a number of notable strengths. First, it prospectively examined the influence of friends on individuals’ experience of alcohol-related consequences associated with 21st birthday celebrations. Friend intentions were collected in advance of the event and were used to predict consequences that followed the event, enhancing this study’s temporal validity. Additionally, the present research focused on a particularly important high-risk drinking context, 21st birthdays. Unlike other high-risk events, such as holidays, 21st birthdays are unique in that these events are intended to celebrate an individual’s attainment of legal rights to consume alcohol. Thus, the focus of the celebration is alcohol consumption. Accordingly, 21st birthdays are associated with heavier drinking and more negative consequences than any other high-risk drinking event (e.g., Spring Break, New Year’s Eve, St. Patrick’s Day; Neighbors et al., 2011; White & Hingson, 2014). Whereas the results of interventions aimed at reducing average drinks per week or drinking on a typical occasion have been encouraging, these approaches do not address the often dangerous drinking that occurs during specific events associated with high-risk drinking (Del Boca et al., 2004; Greenbaum et al., 2005; Neighbors et al., 2005; Neighbors et al., 2006). Our findings elucidate factors that help reduce the negative consequences associated with alcohol consumption on 21st birthdays; namely, having a close friend present who will support the celebrant and help them stay safe.

Our examination of the influence of specific friends present at 21st birthday celebrations provides a significant contribution to the literature on social influences on young adult drinking. Previous research has largely focused on individuals’ perceptions of friends generically or abstractly (e.g., general social group, a “close friend”). By including self-reports from specific close friends who were present at the 21st birthday celebration, we are able to disentangle actual friend influence from potentially biased perceptions of those friends, and we are able to differentiate the positive influence of some friends from the negative influence of others. As this research demonstrates, perceived closeness is not always consistent or reciprocated within friendships, and our findings contribute to the dearth of literature directly examining and comparing actual peer reports and perceived peer reports. Our research fills these important gaps and provides insights for future prevention programs seeking to incorporate close friends.

However, the current research is not withstanding of limitations. Data for the present research were drawn from two conditions of a 21st birthday intervention which incorporated friends who would be present at the celebration. In the larger trial, individuals in both of the friend conditions experienced significantly fewer problems relative to the control group (Neighbors et al., 2012). However, the intervention did not include a control condition that incorporated friends; therefore, the degree to which friends’ reports were influenced by program exposure are unknown. It is possible that friend influence may have been shaped by the intervention. Additionally, participants’ alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences were self-reported; therefore, the extent to which their reports align with their actual behavior and experiences remains unclear, as is the case with much of the research examining alcohol consumption. College students often report considerably lower rates of consumption if they have higher needs for social desirability, or desires to behave in ways that are socially acceptable or pleasing (Davis, Thake, & Vilhena, 2010). However, the high, yet wide range of reported quantity of alcohol consumed during the 21st birthday week (i.e., ranging from 0 to 102 drinks with a mean of 19.48) suggests participants may have been relatively honest in their reports. Given that students generally perceive high alcohol use norms on 21st birthdays (Patrick, Neighbors, & Lee, 2012), students may have been relatively honest while reporting their drinking because they believed high rates of consumption are the norm. Thus, pressures for social desirability may have been reduced in this context.

Another limitation of the present study relates to the nature of the measure of pro-intoxication and pro-safety/support intentions. One of the three items included in each measure was general (i.e., “I encourage [celebrant name]’s drinking”), rather than specific to the 21st birthdays (i.e., “I will encourage [celebrant name] drinking/getting drunk while celebrating his/her 21st birthday)”. It is possible that the friends may not have been thinking about the celebrant’s 21st birthday for the first items. However, this concern is reduced given that participants were recruited for the study explicitly because they were a friend who was going to be present on the celebrant’s 21st birthday and the entire questionnaire they completed was focused on the celebrant’s 21st birthday. Further, it is unclear how friends’ intentions may have translated into actual behaviors during the 21st birthday celebration. A meta-analytic integration of the Theory of Planned Behavior suggested intentions to drink are highly associated with actual drinking behavior (Armitage & Connor, 2001). However, many potential factors may prevent such intentions from coming to fruition (e.g., presence of other friends and partygoers, specials/promotions that make alcohol more accessible or inexpensive). Additional research is needed to examine how and when friends’ intentions reflect actual behaviors on 21st birthdays. Yet, the associations between friends’ intentions and participants’ alcohol-related consequences in the present research suggests consonance between intentions and behavior.

The present findings may not be generalizable to individuals who do not binge drink on their 21st birthdays. The intention to consume four (for women) or five (for men) or more drinks during the 21st birthday was an eligibility requirement for the larger intervention study. However, prior research has shown that approximately 83% of individuals drink on their 21st birthdays, during which they consume an average of 13 drinks (Rutledge, Park, & Sher, 2008). Therefore, the present findings are likely still generalizable to the vast majority of college students celebrating their 21st birthday. However, the extent to which our findings generalize to young adults not enrolled in college, more typical drinking behavior, or other high-risk events remains unknown. For example, young adults not enrolled in college may be less likely to celebrate their 21st birthdays in some of the most dangerous drinking environments (e.g., Greek life parties), and there may be other features of their celebrations and relationships with friends that could alter the extent of the friends’ influence on the celebrant that is different from college students. Further, it is possible that close friends may not exert the same type or amount of influence on individuals’ drinking during a typical night out or during holidays or other celebratory contexts less strongly linked to alcohol consumption. There may be something about 21st birthday celebrations that is inherently conducive to amplifying the influence of friends (e.g., focus on the celebrant) that may not be true of other high-risk drinking events (e.g., Spring Break, Mardi Gras).

Future Directions

From a broad perspective, prior research supports the utility of including close others in interventions, including behavioral couples therapy for alcohol use disorders and reducing HIV risk. Including close friends in alcohol use disorder interventions has received much less attention, but several randomized controlled trials have found that behavioral couples therapy for alcohol use disorder can reduce alcohol consumption and improve healthy relationship functioning (McCrady et al., 1999, 2009; McKay et al., 1993). Whereas couples therapy is quite different from incorporating friends into alcohol interventions, this area of research provides a foundation for prevention approaches that incorporate close others over individual treatment. For example, research on HIV prevention among adolescents has examined the inclusion of friends in interventions (Dolcini et al., 2010; Fang et al., 1998; Harper et al., 2012; Morrison et al., 2007). In line with the present findings, Morrison et al. (2007) found HIV prevention among adolescents to be moderated by friendship closeness. While most outcomes were not moderated by friendship closeness, those that were, were moderated such that the intervention had iatrogenic effects for those who reported greater closeness. Taken together, the results of the present study and findings from previous research support the utility of including specific close friends’ in prevention efforts, as well as the importance of examining their specific characteristics/motivations/intentions, the nature of the relationship with those friends, and the contexts in which these individuals interact.

The results of the present research suggest that future interventions looking to incorporate close friends should focus on training them to promote the use of protective behavioral strategies for their friends during high-risk events. This approach is likely to be more fruitful than attempting to combat the norms surrounding 21st birthday celebrations and reducing individuals’ intentions to get their friends drunk. Even when friends reported higher pro-intoxication intentions, also having high pro-safety/support intentions helped buffer the celebrant from negative alcohol-related consequences. Indeed, the rapidly proliferating body of literature on protective behavioral strategies – behaviors that one can engage in to reduce or limit consumption or risk – is largely founded on the belief that one can remain safe while drinking. Specifically, although one may choose to drink, research suggests it is possible to reduce the amount of consumption, as well as the negative consequences of drinking (Pearson, 2013; Prince, Carey, & Maisto, 2013). However, the benefits of protective behavioral strategies have largely been studied in the context of individuals’ use of these strategies for themselves. There may be a difference in the importance or effectiveness of specific protective behaviors employed for oneself compared to those employed for one’s friends. Additional research is needed to delineate the effects of self- vs. other-oriented protective behavioral strategies.

Furthermore, identifying the behaviors and cognitions through which friends’ intentions manifest protective or harmful influences on 21st birthday drinking is an important direction for future research. Our research demonstrates that friends’ intentions have substantive influences on celebrants’ experience of alcohol-related problems, but it is unclear precisely how this influence may occur. Although speculative, friends who are intent on increasing celebrants’ drinking may purchase or help obtain drinks and encourage the celebrant to continue drinking after intoxication, given that the event is focused specifically on the celebrant. In contrast, friends who are intent on protecting celebrants on their birthday may instead help pace alcohol intake and encourage alternating between alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages, for example. Future research is needed to help elucidate these specific behaviors and pathways of influence.

Conclusion

The current study provides a more complete understanding of how friends can mitigate or exacerbate problems associated with drinking during 21st birthday celebrations. Our findings further elucidate the potential benefits of incorporating close friends in alcohol use intervention efforts, and highlight the particular importance of friends’ intentions to keep celebrants safe on their 21st birthdays. Close friends may be particularly instrumental in reducing negative alcohol-related consequences experienced in relation to 21st birthday celebrations, which are particularly conducive to the consumption of copious amounts of alcohol among this high-risk population.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number R01AA016099 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (PI: Neighbors). Preparation of this article was partially supported by Award Number T32AA007583 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (PI: Leonard). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health. Portions of this data were presented at the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies Annual Meeting in November 2015, the Society for Social and Personality Psychology Annual Meeting in January 2016, the Research Society on Alcoholism Annual Meeting Annual Meeting in June 2016, and the International Association for Relationships Research Biennial Meeting in July 2016.

Footnotes

All significant effects were retained if analyses additionally controlled for the number of hours over which drinks were consumed, as well as if analyses controlled for eBAC instead of number of drinks and hours. Analyses were also run controlling for intervention condition and friend age, and all significant effects were retained.

References

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta‐ analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40(4):471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron A, Aron EN, Smollan D. Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63(4):596–612. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52(5):580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1991.52.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KH, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, Arria AM. Social contexts of drinking and subsequent alcohol use disorder among college students. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2013;39(1):38–43. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.694519. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2012.694519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E, Snyder M, Omoto AM. The Relationship Closeness Inventory: Assessing the closeness of interpersonal relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:792–807. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13(4):391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brister HA, Wetherill RR, Fromme K. Anticipated versus actual alcohol consumption during 21st birthday celebrations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71(2):180–183. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.180. http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2010.71.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla N, Neighbors C, Logan D, Lewis MA, Fossos N. Perceived approval of friends and parents as mediators of the relationship between self-determination and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(1):92–100. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CG, Thake J, Vilhena N. Social desirability biases in self-reported alcohol consumption and harms. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(4):302–311. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.11.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day-Cameron JM, Muse L, Hauenstein J, Simmons L, Correia CJ. Alcohol use by undergraduate students on their 21st birthday: Predictors of actual consumption, anticipated consumption, and normative beliefs. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(4):695–701. doi: 10.1037/a0017213. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0017213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Greenbaum PE, Goldman MS. Up close and personal: temporal variability in the drinking of individual college students during their first year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(2):155–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcini MM, Gandelman AA, Vogan SA, Kong C, Leak TN, King AJ, O’Leary A. Translating HIV interventions into practice: Community-based organizations’ experiences with the diffusion of effective behavioral interventions (DEBIs) Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(10):1839–1846. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotson KB, Dunn ME, Bowers CA. Stand-alone personalized normative feedback for college student drinkers: A meta-analytic review, 2004 to 2014. PloS one. 2015;10(10):e0139518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers N, Spears R, Doosje B. Self and social identity. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53(1):161–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Stanton B, Li X, Feigelman S, Baldwin R. Similarities in sexual activity and condom use among friends within groups before and after a risk-reduction intervention. Youth & Society. 1998;29(4):431–450. doi: 10.1177/0044118X98029004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn CE, Sayette MA. A social-attributional analysis of alcohol response. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140(5):1361–1382. doi: 10.1037/a0037563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, O’Connor RM, Blackwell E, Conrod PJ. Psychometric evaluation of the five-factor Modified Drinking Motives Questionnaire—Revised in undergraduates. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2611–2632. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisner IM, Rhew IC, Ramirez JJ, Lewis ME, Larimer ME, Lee CM. Not all drinking events are the same: Exploring 21st birthday and typical alcohol expectancies as a risk factor for high-risk drinking and alcohol problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;70:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum PE, Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Wang CP, Goldman MS. Variation in the drinking trajectories of freshmen college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(2):229–238. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Willard N, Ellen JM, Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions Connect to Protect®: Utilizing community mobilization and structural change to prevent HIV infection among youth. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2012;40(2):81–86. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2012.660119. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2012.660119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM. Negative binomial regression. Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, White A. Trends in extreme binge drinking among US high school seniors. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167(11):996–998. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, Sher KJ. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health. 1992;41(2):49–58. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH, Thibaut JW. Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. A Journal of the National Association of Social Workers. 1978;25(3):245. doi: 10.1093/sw/25.3.245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH. An atlas of interpersonal situations. Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999–2006. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD, Atkins DC, Burlingham B, Lonczak HS, Marlatt GA. Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. Jama. 2009;301(13):1349–1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Gender-specific misperceptions of college student drinking norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(4):334–339. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.334. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Lindgren KP, Fossos N, Neighbors C, Oster-Aaland L. Examining the relationship between typical drinking behavior and 21st birthday drinking behavior among college students: implications for event‐specific prevention. Addiction. 2009;104(5):760–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Lindgren KP, Buckingham KG, Hoang M. Social Influences on Adolescent and Young Adult Alcohol Use. Happauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers Inc; 2010. pp. 101–140. [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Page JC, Mowry ES, Damann KM, Taylor KK, Cimini MD. Differences between actual and perceived student norms: an examination of alcohol use, drug use, and sexual behavior. Journal of American College Health. 2006;54(5):295–300. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.5.295-300. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JACH.54.5.295-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Cook S, Jensen N, Hildebrandt T. A randomized trial of individual and couple behavioral alcohol treatment for women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(2):243. doi: 10.1037/a0014686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Hirsch LS. Maintaining change after conjoint behavioral alcohol treatment for men: Outcomes at 6 months. Addiction. 1999;94(9):1381–1396. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.949138110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Maisto SA, O’Farrell TJ. End-of-treatment self-efficacy, aftercare, and drinking outcomes of alcoholic men. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17(5):1078–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison DM, Casey EA, Beadnell BA, Hoppe MJ, Gillmore MR, Wilsdon A, Wells EA. Effects of friendship closeness in an adolescent group HIV prevention intervention. Prevention Science. 2007;8(4):274–284. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Atkins DC, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Kaysen D, Mittmann A, Rodriguez LM. Event-specific drinking among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25(4):702–707. doi: 10.1037/a0024051. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Neil TA. Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(2):290–299. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Desai S, Larimer ME. Group identification as a moderator of the relationship between perceived social norms and alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(3):522–528. doi: 10.1037/a0019944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Atkins DC, Lewis MA, Kaysen D, Mittmann A, Larimer ME. A randomized controlled trial of event-specific prevention strategies for reducing problematic drinking associated with 21st birthday celebrations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(5):850–862. doi: 10.1037/a0029480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Spieker CJ, Oster-Aaland L, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL. Celebration intoxication: An evaluation of 21st birthday alcohol consumption. Journal of American College Health. 2005;54(2):76–80. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.2.76-80. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JACH.54.2.76-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Neighbors C, Lee CM. A hierarchy of 21st birthday drinking norms. Journal of College Student Development. 2012;53(4):581–585. doi: 10.1353/csd.2012.0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR. Use of alcohol protective behavioral strategies among college students: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33(8):1025–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.006. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince MA, Carey KB, Maisto SA. Protective behavioral strategies for reducing alcohol involvement: a review of the methodological issues. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(7):2343–2351. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.03.010. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/i.addbeh.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Real K, Rimal RN. Friends talk to friends about drinking: exploring the role of peer communication in the theory of normative behavior. Health Communication. 2007;22(2):169–180. doi: 10.1080/10410230701454254. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10410230701454254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge PC, Park A, Sher KJ. 21st birthday drinking: Extremely extreme. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(3):511–516. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey KB, Elliott JC, Garey L, Carey MP. Efficacy of alcohol interventions for first-year college students: A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(2):177–188. doi: 10.1037/a0035192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A, Hingson R. The burden of alcohol use: Excessive alcohol consumption and related consequences among college students. Alcohol Research. 2014;35(2):201–218. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v35.2.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]