Abstract

Rationale: Dysregulated neutrophil functions with age and sepsis are described. Statins are associated with improved infection survival in some observational studies, but trials in critically ill patients have not shown benefit. Statins also alter neutrophil responses in vitro.

Objectives: To assess neutrophil migratory accuracy with age during respiratory infections and determine if and how a statin intervention could alter these blunted responses.

Methods: The migratory accuracy of blood neutrophils from young (aged <35 yr) and old (aged >60 yr) patients in health and during a lower respiratory tract infection, community-acquired pneumonia, and pneumonia associated with sepsis was assessed with and without simvastatin. In vitro results were confirmed in a double-blind randomized clinical trial in healthy elders. Cell adhesion markers were assessed.

Measurements and Main Results: In vitro neutrophil migratory accuracy in the elderly deteriorated as the severity of the infectious pulmonary insult increased, without recovery at 6 weeks. Simvastatin rescued neutrophil migration with age and during mild to moderate infection, at high dose in older adults, but not during more severe sepsis. Confirming in vitro results, high-dose (80-mg) simvastatin improved neutrophil migratory accuracy without impeding other neutrophil functions in a double-blind randomized clinical trial in healthy elders. Simvastatin modified surface adhesion molecule expression and activity, facilitating accurate migration in the elderly.

Conclusions: Infections in older adults are associated with prolonged, impaired neutrophil migration, potentially contributing to poor outcomes. Statins improve neutrophil migration in vivo in health and in vitro in milder infective events, but not in severe sepsis, supporting their potential utility as an early intervention during pulmonary infections.

Clinical trial registered with www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu (2011-002082-38).

Keywords: neutrophil, immunosenescence, pneumonia, sepsis, statins

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

The elderly have a high incidence of pneumonia and experience a great impact from it, especially when sepsis develops. Impaired neutrophil responses during severe infections and sepsis have been associated with poor outcomes. Little is known about neutrophil functions during mild to moderate infective events. Therapeutic interventions with statins aimed at improving poor clinical outcomes and immune responses have been focused on critically ill patients, without success.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Inaccurate neutrophil migration seen in aging deteriorates further with infection severity. Sepsis was associated with severe impairment of migration that did not recover weeks after the initial event. When used at high dose in elderly subjects in health or in vitro in milder infective events, simvastatin improved neutrophil migratory accuracy without impeding other vital bactericidal functions, suggesting a therapeutic role if used early as adjuvant therapy. Simvastatin could not restore neutrophil functions in vitro in more severe sepsis episodes, corroborating interventional trial results.

Pneumonia is the leading infectious cause of death in developed countries. Deaths are highest in the elderly, with mortality rates not improved over the last decade (1). Neutrophils are key effector cells during bacterial infections, with evidence of suboptimal immune responses in the elderly contributing to poor outcomes (2). Age is associated with reduced neutrophil migratory accuracy (3), phagocytosis (4), and neutrophil extracellular trap release by dying cells (“NETosis”) (5) in vitro, although degranulation appears increased (3). Poor migratory accuracy, reduced bactericidal function, and enhanced degranulation may delay pathogen clearance and increase bystander tissue damage through excess protease activity. Consistent with this, older adults experience greater end-organ damage after severe infections (6).

Sepsis-related organ dysfunction is caused by complex, dysregulated host responses to infection and is more common in the elderly (7). Patients with severe sepsis demonstrate a sustained proinflammatory cytokine profile (8), abrogated antiinflammatory signaling (9), and dysregulated neutrophil functions (8). This results in a hostile yet immunoparetic systemic environment. Secondary infections are common after sepsis and are associated with immune suppression (10).

Given the increasing incidence of sepsis, there is interest in enhancing immune responses to clear infections before sepsis develops. To date, there are no treatments that improve immune cell function during established sepsis (11). Although variable, most infections begin with a milder syndrome that progresses to sepsis in vulnerable individuals. It is unknown if milder infections are associated with immune dysfunction that deteriorates as the severity of insult increases or at what point during the infective process immune cells are susceptible to therapeutic interventions.

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) lower cholesterol, but some population studies and clinical trials have suggested survival benefits during infection (12). Predosing with statins improves outcomes in murine models of sepsis (13). However, preclinical studies did not translate to positive outcomes in a recent trial of patients with severe sepsis–related acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (14).

Statins alter neutrophil functions in vitro, including migration and NETosis (15, 16), with mechanisms such as reduced adhesion molecule expression proposed (17). Neutrophil adhesion molecule expression increases with sepsis (18, 19), but it is unclear whether statins alter neutrophil adhesion molecule expression during infections and whether this might improve or hinder cellular responses to infection. There are many unanswered questions about the non–cholesterol-lowering effects of statins, and there is considerable interest in how statins might improve inflammatory outcomes. Currently, 209 clinical trials designed to study these effects are registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (20).

We hypothesized that poorer outcomes during infections in the elderly reflect a progressive exaggeration of the age-related decline in neutrophil function. Furthermore, we proposed that statins would restore aspects of neutrophil function during these events but that there would be a window of opportunity for therapeutic response.

The aims of the present study were as follows:

-

1.

To assess whether age-associated reductions in neutrophil migratory accuracy (3) are exaggerated during episodes of lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI), community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), and pneumonia associated with sepsis (severe community-acquired pneumonia [S-CAP]);

-

2.

To determine if in vitro treatment with simvastatin improves neutrophil migration in health, LRTI, CAP, and S-CAP, and at which concentration;

-

3.

To assess the effects of oral simvastatin on systemic neutrophil functions in healthy older subjects in a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial; and

-

4.

To determine the likely mechanisms of effect.

Some of the results of these studies were reported previously in the form of an abstract (21).

Methods

Study Subjects

All patients were either older than 60 years of age or younger than 35 years of age and were recruited between 2011 and 2016. Healthy old (OH) and healthy young (YH) subjects, identified from among the Birmingham 1000 Elders cohort (3), had never smoked, had no evidence of acute or chronic disease, had normal spirometry, were medication free, and had no previous episodes of hospitalized sepsis. Older subjects on statins (OS) were taking 40 mg of simvastatin due to cardiovascular risk (with no previous cardiovascular events).

Patients with LRTI, CAP, and S-CAP were recruited within 24 hours of admission to the hospital. LRTI was diagnosed by the presence of increased breathlessness as well as a cough productive of purulent sputum without associated consolidation on chest radiograph and without sepsis (22). CAP was diagnosed using standard criteria (23), including symptoms of a respiratory infection and new chest radiograph consolidative changes, and patients had CURB (confusion, urea, respiratory rate, and blood pressure) scores of 1–2 (excluding the point given for age), indicating mild to moderate severity (24), and were without sepsis. Patients with S-CAP met criteria for pneumonia (23) and sepsis (22). In this research, we used the 2012 definition of sepsis to allow comparison with published literature (22). The newer 2015 definition identifies a population at high risk of in-hospital mortality but excludes milder infections, which we sought to investigate in this study (25). All diagnoses were confirmed by a senior pulmonologist. All subjects with capacity gave written informed consent, and those without such capacity were recruited using a personal consultee after approval from the South Central Oxford Research Ethics Committee (reference 11/SC/0356). A detailed description of the methods used is provided in the online supplement, including sputum sol, which was prepared as previously described (26).

Isolation of Blood Neutrophils

Neutrophils were isolated from whole blood as described previously (3) and were greater than 95% pure and greater than 97% viable by exclusion of trypan blue.

Neutrophil Migration

Migration was assessed using an Insall chamber (Weber Scientific International Ltd., Teddington, UK) as described previously (3). (A full description of the methods is provided in the online supplement.) Neutrophils were adhered to coverslips coated with 7.5% culture-tested bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, UK) (suspended at 2 × 106/ml). The chamber was filled with RPMI 1640 (control) medium, 100 nM IL-8 (CXCL8) (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK), or 100 nM formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP; Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were incubated with simvastatin hydroxy acid (Sigma-Aldrich) at 500 pM–1 µM. This range was chosen because it includes concentrations that have been described in patients taking simvastatin orally (27) (26 nM BIRT-377, a CD11a inhibitor [28]; Tocris Bioscience, Abingdon, UK) or relevant vehicle control (VC) for 40 minutes prior to migration.

Videomicroscopy for Migratory Dynamics

For time-lapse recordings, we used a DMI6000 B inverted microscope fitted with a DFC360 FX camera (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Recordings lasted 12 minutes, with slides captured using Leica LAS AF software (Leica Microsystems). ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was used to analyze cell tracks. All analysis was performed by a single analyst who was blinded to subject group and cell condition.

Neutrophil migratory accuracy (termed “chemotaxis” and measured in μm/min) was defined as distance traveled over time only in the direction of the stable chemotactic gradient formed using the Insall chamber (29). This is different from migratory speed, which is movement in any direction over time (termed “chemokinesis”).

Neutrophil Phagocytosis and NET Generation

Neutrophil phagocytosis was assessed using the commercial pHrodo assay (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were expressed as phagocytic index: phagocytic index = percentage of phagocytosing neutrophils multiplied by mean fluorescence intensity. Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) production was measured as described previously (5) in quiescent or stimulated neutrophils (with fMLP 100 nM and LPS 100 nM) and phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate 25 nM (used as a positive control); cell-free DNA was labeled; and the degree of fluorescence was measured. NET release was confirmed by light microscopy.

Placebo-controlled Double-Blind Crossover Trial of Simvastatin in the Healthy Elderly

In a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover trial, we recruited healthy elderly subjects to receive oral simvastatin 80 mg or placebo once daily for 2 weeks, followed by a 2-week washout period and then the alternative, blinded therapy. Computer-based block randomization was performed in a 1:1 ratio by a centralized service (Bilcare Ltd., Pune, India). Participants had blood samples taken before randomization and after the first and second 2-week interventions. The primary outcome was an improvement from baseline in neutrophil chemotaxis. Secondary endpoints were changes in other neutrophil functions, safety, and tolerability. The trial protocol is summarized in Table E1 in the online supplement, where inclusion and exclusion criteria are given. Throughout this trial, both participants and researchers were blinded to treatment, and researchers remained blinded to treatment until all study assays were complete (including cholesterol levels).

Neutrophil Adherence

Neutrophil adherence (expressed as a percentage) was calculated as the number of adherent cells present within the field of view divided by the total number of cells in the field multiplied by 100. Adherence was defined by plotting visual appearance using ImageJ software; those neutrophils with a polarized morphology with a clear leading edge and uropod at the rear of the cell were considered adherent, compared with spherical cells without a polarized morphology, which were classified as nonadherent cells. This was assessed by two independent viewers blinded to the experimental condition and the median result reported.

Adhesion Markers

Quantities of 100 µl of whole blood were collected in lithium heparin vacutainers, washed, and resuspended in 2% phosphate-buffered saline/bovine serum albumin containing 5% autologous plasma. Whole blood was incubated with or without 1 µM simvastatin or VC for 40 minutes at 37°C prior to staining. Marker expression was determined by flow cytometry (Accuri C6; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), counting 10,000 events. Data are presented as median fluorescence index minus signal from irrelevant antibody or as percentage change in median fluorescence index, as stated in the text. Antibodies used are reported in the online supplement.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics version 18.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Data were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, but differences between groups were assessed using nonparametric tests owing to sample size, including Wilcoxon signed-rank, Mann-Whitney U, Kruskal-Wallis, and Friedman’s tests. Differences between categorical variables were assessed using χ2 tests, and correlations were evaluated using Spearman’s correlation coefficients.

Randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover trial

There were no previous studies of the impact of oral simvastatin on neutrophil function on which to base accurate power calculations. In our in vitro studies, we found mean differences of effect between 1.8 μm/min (SD, 0.6 μm/min; OH neutrophils incubated with simvastatin 1 μM or VC) and 0.67 μm/min (SD, 0.52; comparing adults taking simvastatin 40 mg with those not on simvastatin therapy), and using these data, we predicted that approximately 18 participants completing each arm would be required to detect a significant improvement in neutrophil chemotaxis with a power of 80%. To allow for dropouts, a recruitment target of 24 participants was selected. Differences between pre- and post-treatment values for each group were used for data analysis. The Holm-Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons.

All statistical tests were two sided, with P < 0.05 accepted as statistically significant. Figure legends provide information on which statistical tests were employed.

Results

Participant demographics and baseline sepsis severity scores are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Data of Participants

| OH* | YH* | LRTI |

CAP |

S-CAP |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old | Young | Old | Young | Old | Young | Prior Statin Use† | |||

| Subjects, n | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Age, yr, median (range) | 72 (64–78) | 27 (21–32) | 75 (65–81) | 29 (21–32) | 73 (66–86) | 31 (23–34) | 76 (65–84) | 29 (19–34) | 74 (62–78) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 5 (50%) | 5 (50%) | 6 (60%) | 5 (63%) | 7 (70%) | 6 (60%) | 6 (60%) | 6 (60%) | 6 (60%) |

| CAP based on radiograph, n | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| Temperature, °C, median (range) | 37.2 (36.3–37.4) | 37.3 (36.7–37.4) | 37.3 (36.5–37.4) | 37.5 (37.4–37.9) | 37.6 (36.0–37.6) | 37.7 (36.3–37.9) | 38.1 (35.2–38.9) | 38.8 (37.5–40.2) | 36.9 (36.6–37.0) |

| RR, breaths/min, median (range) | 14 (12–16) | 14 (12–18) | 16 (12–20) | 15 (14–18) | 18 (12–20) | 19 (14–20) | 26 (18–38) | 28 (16–34) | 16 (14–18) |

| HR, beats/min, median (range) | 68 (60–88) | 74 (72–90)‡ | 92 (62–102) | 90 (640,100) | 98 (65–102) | 93 (72–114) | 116 (97–127) | 110 (100–145) | 75 (69–86) |

| WCC, 109/L, median (range) | N/A | N/A | 13.8 (10–17) | 14.3 (9–15) | 17.4 (11–24) | 16.7 (12–23) | 19.2 (15–23) | 19.4 (16–29) | N/A |

| SOFA score | N/A | N/A | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | N/A |

| APACHE II score | N/A | N/A | 3 (2–5)‡ | 0 (0–1) | 6 (5–8)‡ | 4 (2–4) | 24 (12–28)‡ | 12 (5–32) | N/A |

| CRP, mg/L, median (range) | 2 (0–4) | 4 (2–5)‡ | 33 (12–46)‡ | 19 (8–22) | 91 (52–139)‡ | 69 (21–97) | 159 (84–181)‡ | 116 (98–146) | 3 (1–4) |

Definition of abbreviations: APACHE II = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; CAP = community-acquired pneumonia; CRP = C-reactive protein; HR = heart rate; LRTI = lower respiratory tract infection; N/A = not applicable; OH = healthy old subjects; RR = respiratory rate; S-CAP = pneumonia associated with sepsis/severe community-acquired pneumonia; SOFA = Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; WCC = total white blood cell count; YH = healthy young subjects.

The table shows demographic data, baseline severity scores, and clinical data for healthy subjects; patients with LRTI, CAP, or S-CAP; and patients on statins. CAP based on radiograph is the number of participants with new consolidation seen on chest radiographs. Temperature is the temperature on admission. Sepsis was defined as the presence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome, which includes two or more of a temperature below 36°C or above 38°C, a heart rate greater than 90 beats per minute, a respiratory rate greater than 20 breaths per minute, and leukocytosis greater than 12 × 10 × 106 white blood cells per milliliter. All medical diagnoses were confirmed by a physician and by laboratory cultures where relevant. SOFA and APACHE II scores were obtained on the day of recruitment. Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare parameters of old versus young subjects.

These subjects were medication free.

Among patients being treated with statins, three were taking β-blockers (5–10 mg bisoprolol), two were taking amlodipine 5–10 mg, two were taking ramipril (10 mg), and five were taking bendroflumethiazide (2–5 mg) as regular medication.

P < 0.05 for difference from young participants in the same group.

Neutrophil Migratory Accuracy Declines with Increasing Infectious Insult in OH Subjects

Neutrophils from OH were less able to migrate accurately to CXCL8 than those isolated from YH (mean chemotaxis (±SEM), OH, 1.3 ± 0.1 µm/min; YH, 1.8 ± 0.2 µm/min; P < 0.001 by Mann-Whitney U test; n = 10 in each group). Cross-sectionally, there was a progressive decrease in the ability of systemic neutrophils from old subjects to accurately migrate (chemotaxis) toward CXCL8 as the severity of their infection worsened from LRTI to CAP to S-CAP (P < 0.0001 by Kruskal-Wallis test). In contrast, neutrophils from young subjects displayed a different response, with no deterioration in neutrophil migratory accuracy across patient groups (nonsignificant by Kruskal-Wallis test) but a reduction of accuracy during S-CAP compared with health (P = 0.01 by Mann-Whitney U test) (see Figure 1A). There were no differences in treatment for the acute infection between young or old patients with LRTI, young or old patients with CAP, or young or old patients with S-CAP to account for these differences.

Figure 1.

Changes to neutrophil chemotaxis during respiratory infections and recovery. (A) Neutrophil chemotaxis during infections. Neutrophils were isolated from healthy control subjects aged 60 years or older (n = 10) or younger than 35 years (n = 10) and from age-matched patients within 24 hours of being treated for a lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI; n = 10 aged >60 yr and n = 8 aged <35 yr), community-acquired pneumonia (CAP; n = 10 aged >60 yr and n = 10 aged <35 yr), or pneumonia associated with sepsis (severe community-acquired pneumonia [S-CAP]; n = 10 for both age groups). Each data point represents a single subject, and the median and interquartile range are shown with error bars. In older subjects, neutrophil migration displayed reduced accuracy toward IL-8 (CXCL8; 100 nM) as the infectious insult severity progressed (P = 0.0001 by Kruskal-Wallis test). A post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparison test confirmed there was no significant difference between older healthy control subjects and patients with LRTI (adjusted P = 0.32), but there was a statistical difference between healthy control subjects and older patients with CAP (P = 0.0021), S-CAP (P < 0.0001), and LRTI and S-CAP (P = 0.011), but not between CAP and S-CAP (adjusted P = 0.845). In young adults, no such deterioration was seen (across infectious insults; P = nonsignficant by Kruskal-Wallis test), but neutrophil migratory accuracy was reduced in sepsis compared with health (P = 0.01 by Mann-Whitney U test). (B) Changes to neutrophil chemotaxis during pneumonia and 6 weeks after recovery. Neutrophils were isolated from young (aged <35 yr) and old (aged >60 yr) patients admitted with CAP (n = 10 for each group) and 6 weeks later, after a clinical recovery as demonstrated by no symptoms compatible with infection; no physiological, biochemical, or hematological evidence of infection; and a chest radiograph demonstrating recovery (CAP-R). Each data point represents a single subject with CAP, and recovery data for the same patient are linked by dashed lines. Cells migrated toward CXCL8 (100 nM). CAP-R results were compared with age-matched either old or young healthy control subjects (HC) who self-reported never having had pneumonia (n = 10 for each group).

Responses to single chemokines may not reflect responses to complex biological secretions, so neutrophils from older and younger patients with pneumonia (n = 5 per group) migrated toward pooled “pneumonia” sputum from old patients. Neutrophils from old patients with CAP displayed a reduced ability to migrate toward this complex, inflammatory biological stimulus compared with neutrophils from young patients with CAP (chemotaxis; OH, 0.6 ± 0.2 μm/min; YH, 2.2 ± 0.2 μm/min; P = 0.008 by Mann-Whitney U test), replicating the single-chemokine results.

Migratory studies were repeated in the subjects with CAP (n = 10 for both young and old CAP groups) 6 weeks after admission, after a physician-confirmed resolution of chest radiograph changes and no symptoms or signs of infection. CAP and recovery (CAP-R) results were compared with age-matched control subjects who self-reported never having had pneumonia (n = 10 for each group). Neutrophils from younger subjects did not alter in their migratory accuracy during or after infection or when compared with those of other young healthy control subjects (median [range] chemotaxis, CAP, 2.64 [1.24–3.21] μm/min; CAP-R, 1.88 [1.26–2.54] μm/min; YH, 1.81 [1.09–2.66] μm/min). Neutrophils from old patients with CAP did not improve their migratory accuracy at 6 weeks postinfection, and neutrophil migratory accuracy did not reach average levels seen in OH adults (median [range] chemotaxis, CAP, 0.51 [−0.16 to 1.03] μm/min; CAP-R, 0.72 [0.16 to 1.57] μm/min; healthy control subjects, 1.22 [0.93 to 1.92] μm/min; P = 0.002 by Mann-Whitney U test for CAP-R compared with OH) (see Figure 1B).

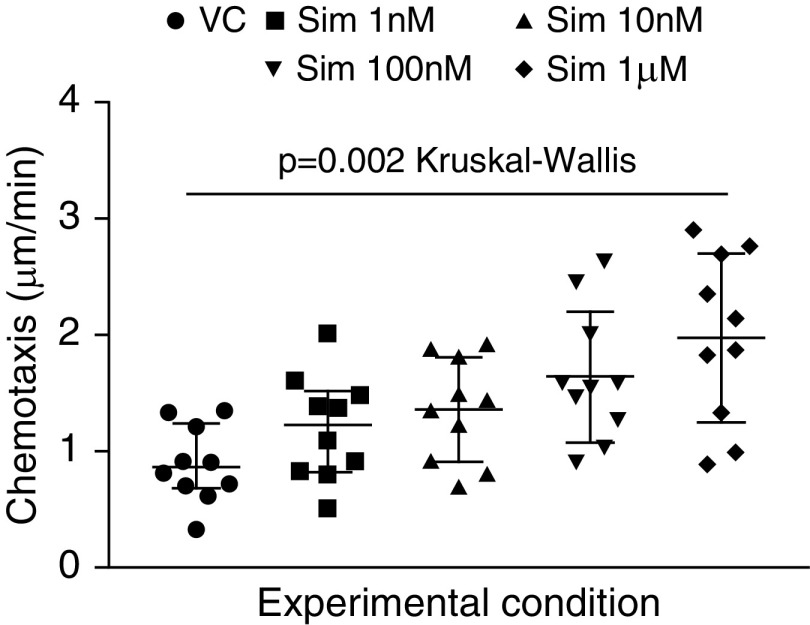

In Vitro Simvastatin Exposure and Neutrophil Migratory Dynamics

A dose–response analysis was conducted with simvastatin (500 pM–1 µM) incubated with neutrophils isolated from OH (n = 10). Simvastatin improved neutrophil migratory accuracy, with 1 µM simvastatin being optimal (Figure 2). When OH and YH participants were compared, 1 µM simvastatin increased chemotaxis in neutrophils from OH subjects but not in neutrophils from YH subjects (OH VC, 0.43 ± 0.1 μm/min; simvastatin, 2.2 ± 0.1 μm/min; P = 0.001; YH VC, 1.4 ± 0.2 μm/min; simvastatin, 1.8 ± 0.2 μm/min; P = nonsignificant by Wilcoxon signed-rank tests).

Figure 2.

Changes to neutrophil chemotaxis after in vitro exposure to simvastatin (dose response). Neutrophils were isolated from healthy subjects aged 60 years or older (n = 10) and incubated for 40 minutes with simvastatin (Sim) at the concentrations given or with vehicle control (VC). Each data point represents a single subject, and the median and interquartile range are shown as a horizontal line with error bars. The accuracy of neutrophil migration toward IL-8 (CXCL8; 100 nM) was assessed and found to be improved after incubation with 1 nM–1 μM statin compared with VC across the whole group (P = 0.0022 by Kruskal-Wallis test). A post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparison test confirmed that there were significant differences between neutrophil migratory accuracy when incubated with 100 nM (adjusted P = 0.023) and 1 μM (adjusted P = 0.0018) simvastatin compared with VC.

Neutrophils from Old Patients Taking Simvastatin 40 mg Daily Have an Augmented Migration Response When Exposed to High-Dose Simvastatin In Vitro

Simvastatin after a single in vitro exposure was assessed in previous experiments, but clinical studies support the benefits of a priori use (30). Isolated neutrophil migration was assessed in OS (n = 10) taking simvastatin 40 mg daily with self-reported compliance. Demographic information is provided in Table 1. Simvastatin use was associated with increased neutrophil migratory accuracy compared with age-matched adults not taking statins (chemotaxis, OH, 0.43 ± 0.1 μm/min; OS, 1.1 ± 0.2 μm/min; P = 0.008). Incubation of statin users’ neutrophils with 1 µM simvastatin improved migratory accuracy toward CXCL8 (chemotaxis; VC, 1.1 ± 0.2 μm/min; simvastatin treatment, 1.8 ± 0.3 μm/min; P = 0.02), suggesting that high-dose therapy may have immune effects even in prior statin users (Mann-Whitney U test used for all comparisons).

Statins Improve Neutrophil Migration during Respiratory Infections but Not Sepsis in Older Patients

Neutrophils from patients with LRTI, CAP, and S-CAP (described in Table 1) were incubated with simvastatin (1 µM) or VC. Simvastatin improved neutrophil migration from old patients with LRTI and CAP but had no effect on neutrophils from patients with S-CAP (Figure 3A). Simvastatin did not improve neutrophil migratory accuracy in young patients with LRTI, CAP, or S-CAP (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Changes to neutrophil chemotaxis in patients during respiratory infections: the effects of in vitro simvastatin. Peripheral neutrophils were isolated from (A) old (aged >60 yr) or (B) young (aged <35 yr) patients with lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI; old, n = 10; young, n = 8), community-acquired pneumonia (CAP; n = 10 for both age groups), and pneumonia associated with sepsis (severe community-acquired pneumonia [S-CAP]; n = 10 for both age groups) and incubated with 1 µM simvastatin or vehicle control (VC) for 40 minutes. In both figure parts, each data point represents a single subject, and the median and interquartile range are shown as a horizontal line with error bars. Simvastatin improved migration of neutrophils from old patients with LRTI (P = 0.008) and also of those from old patients with pneumonia (P = 0.01), but not of neutrophils from patients with sepsis, whose neutrophils remained poorly chemotactic (Wilcoxon signed-rank test for all). Simvastatin did not impact migration of neutrophils from young adults in any group.

These cross-sectional in vitro results suggest that neutrophil migratory accuracy declines with the severity of an infective insult in older adults and does not reach levels seen in OH adults after clinical recovery. Simvastatin can restore neutrophil migratory accuracy in vitro, in health, and during mild to moderate respiratory infections, but not during a severe septic event and only at high doses in cells from older adults.

Simvastatin Improves Neutrophil Migratory Accuracy in the Healthy Elderly without Inhibiting Other Cell Functions: Randomized Controlled Trial Outcomes

To assess if these in vitro results could be reproduced in vivo, a proof-of-concept, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial was performed with OH adults given simvastatin 80 mg or placebo orally. A modified Consolidate Standards of Reporting Trials diagram for the trial is given in Figure 4. Participant demographics are shown in Table 2.

Figure 4.

Modified Consolidate Standards of Reporting Trials diagram of the screening and recruitment of subjects in the randomized, controlled, double-blind crossover study of simvastatin 80 mg orally daily or placebo, showing the number of subjects who had complete sets of functional neutrophil experiments performed.

Table 2.

Demographic and Physiological Characteristics of Trial Participants upon Recruitment

| Patient Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age, yr, mean (range) | 71.9 (60–94) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 9 (43%) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never, n | 13 |

| Ex-smoker, n (pack-year history) | 6 (21.5) |

| Current, n (pack-year history) | 2 (21.5) |

| Comorbid conditions | |

| Hypertension | 6 |

| Medications | |

| Antihypertensive drugs | |

| ACEi | 1 |

| Diuretics | 1 |

| Ca2+ channel blocker + diuretic | 3 |

| β-Blocker | 1 |

| Oxygen saturation, % | 97 (96–98) |

| FEV1, L/s, mean ± SD (% predicted) | 2.67 ± 0.7 (115.5 ± 19.1) |

| FVC, L, mean ± SD (% predicted) | 3.57 ± 0.8 (123.3 ± 21.9) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 26.04 ± 3.7 |

| Blood pressure, mm Hg | 142 (132–149) |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 79 (69.5–80.5) |

| ALT, μmol/L | 17 (15–22) |

| Bilirubin, μmol/L | 8 (7–10) |

| CK, IU/L | 80 (59.5–134.5) |

| TSH, mIU/L | 1.9 (1.1–3.7) |

Definition of abbreviations: ACEi = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; BMI = body mass index; CK = creatine kinase; TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone.

All values represent median (interquartile range), unless otherwise stated.

Trial Outcomes

The subjects’ mean age was 71.9 years (range, 60–94 yr), and the sex distribution was similar (9 vs.12 males; P = 0.661 by χ2 test). Treatment compliance was excellent, with only one subject forgetting a single dose. Total cholesterol (measured as a surrogate for compliance) was studied after trial completion. Placebo had no impact on serum cholesterol levels, whereas simvastatin treatment significantly reduced cholesterol levels and was well tolerated (see online supplement).

Neutrophil chemotaxis was significantly improved from baseline in subjects after simvastatin treatment when neutrophils migrated toward fMLP (median change in migratory accuracy, 0.34 μm/min [interquartile range {IQR}, 0.05 to 0.72] vs. −0.05 μm/min [IQR, −0.38 to 0.08 μm/min]; P = 0.006). A trend toward improvement in neutrophil migratory accuracy was seen when migrating toward CXCL8, but this was not significant after correction for multiple comparisons (median change, 0.26 μm/min [IQR, 0.01 to 0.61] vs. 0.03 μm/min [IQR, −0.73 to 0.34]; P = 0.042). Simvastatin treatment did not affect neutrophil phagocytosis or NETosis (see Figure 5 and Table 3); all these analyses were done using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

Figure 5.

Changes in neutrophil migratory accuracy after a 2-week course of high-dose simvastatin and placebo. Healthy older adults had neutrophil migratory accuracy measured at baseline toward IL-8 (CXCL8) and formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP). They were then randomized in a double-blind crossover trial to receive simvastatin 80 mg or placebo for 2 weeks, after which neutrophil migration toward the chemoattractants was reassessed. There was a 2-week washout period, and then the alternative blinded therapy was taken, with neutrophil functions reassessed at the end of this 2-week course. (A) Neutrophil migration at baseline compared with after simvastatin treatment. (B) Neutrophil migration at baseline compared with after placebo treatment. Each data point represents one subject, with pre- and post-treatment or placebo neutrophil migration indices linked by lines. The median difference between baseline and treatment or placebo neutrophil migration was assessed using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, and the Holm-Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons. *Statistically significant after multiple comparison correction. $Not statistically significant after multiple comparison correction.

Table 3.

Results of the Randomized, Double-Blind Crossover Clinical Trial of Simvastatin in Healthy Older Adults

| Baseline | Placebo |

Simvastatin |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Treatment | Difference | Post-Treatment | Difference | P Value | ||

| Phagocytosis | ||||||

| Escherichia coli | 936.8 (492.4 to 1,675) | 1,497 (1,171 to 2,059) | 690.0 (−79.0 to 1,207) | 1,548 (1,282 to 2,158) | 580 (−22.0 to 1,347) | 0.404 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1,291 (660.1 to 2,494) | 1,570 (1,128 to 2,214) | 1,217 (−588.7 to 2,048.0) | 1,525 (997.8 to 1,959) | 257 (−616.7 to 1,951) | 0.196 |

| NETosis | ||||||

| PMA | 47,566 (27,859 to 65,272) | 44,363 (31,546 to 56,273) | 6,964 (−17,992 to 22,048) | 46,974 (32,631 to 55,913) | 5,985 (−24,415 to 30,189) | 0.729 |

| fMLP | 1,570 (−1,029 to 3,416) | −416 (−1,618 to 700) | 1,099 (−2,818 to 2,719) | 3,196 (−2,749 to 6,856) | 1,355 (−2,133 to 6,518) | 0.216 |

| LPS | 1,202 (−1,067 to 2,299) | 1,451 (34.1 to 3,496) | 4,048 (2,833 to 6,279) | 1,202 (−1,067 to 2,299) | 7,115 (−839.1 to 9,851) | 0.596 |

Definition of abbreviations: fMLP = formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine; NETosis = neutrophil extracellular trap release by dying cells; PMA = phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate.

All data are presented as median change and interquartile range with P values derived from Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Values show baseline median and interquartile range results and the change from baseline neutrophil function after treatment with simvastatin and placebo (n = 20 in each group). Phagocytosis was assessed using the phagocytic index. NETosis was assessed using arbitrary fluorescence units.

Mechanism of Action: Effect on Adhesion and Adhesion Markers

Neutrophils from old subjects in health and with LRTI, CAP, and S-CAP (n = 10 per group) displayed increased coverslip adherence as the infectious insult increased (median percentage adherent [IQR], OH, 51% [39–64]; LRTI, 61% [38–87]; CAP, 68% [55–98]; S-CAP, 91% [82–100]; P = 0.008 by Kruskal-Wallis test). Although a similar pattern was seen in young patients, this was not significant (median percentage adherent [IQR], YH [n = 10], 35% [28–41]; LRTI [n = 8], 40% [29–53]; CAP [n = 10], 42% [29–62]; S-CAP [n = 10], 86% [53–100]; P = 0.1).

To determine if increased adhesion reflected changes in surface expression of adhesion markers, CD11a, CD11b, CD18, and activated CD11b were measured on quiescent neutrophils in whole blood. CD11b and CD11a expression was higher on neutrophils from OH than on those from YH (n = 10 in each group). Surface expression of CD11b and CD11a were then measured on neutrophils in whole blood from old patients with CAP and compared with those of OH (n = 10 in each group) with higher expression of CD11a. Incubating OH whole blood with 1 μM simvastatin in vitro (or VC) was associated with a reduction in CD11a expression on neutrophils compared with VC (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Neutrophil Surface Expression of Adhesion Markers

| CD11a | CD11b | CD18 | Activated CD11b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YH | 1,105 (930.5–1,344.0) | 3,065.5 (2,709–3,486) | 43,722 (33,220–48,463) | 1,728 (1,473–2,086) |

| OH | 2,043.6 (1,770–2,171)* | 4,131 (3,644–4,812)† | 48,074 (41,633–51,738) | 2,116 (1,936–3,149) |

| Old CAP | 2,648 (2,113–3,126)‡ | 4,839 (4,149–6,509)§ | Not measured | Not measured |

| OH simvastatin | 1,356 (1,141–1,623)|| | 3,674 (3,407–3,906) | Not measured | Not measured |

| OH VC | 1,830 (1,643–2,301.2) | 3,659 (3,351–4,112) | Not measured | Not measured |

Definition of abbreviations: OH = old healthy control subjects; OH simvastatin = whole blood from old healthy control subjects treated with 1 μM simvastatin; OH VC = whole blood from old healthy control subjects treated with vehicle control for simvastatin; Old CAP = old patients with community-acquired pneumonia; YH = young healthy control subjects.

All measurements were conducted in cells in whole blood (see Methods section of text). Data are expressed as median fluorescence index (interquartile range) and compared using Mann-Whitney U tests. There were 10 subjects in each group.

P = 0.0007 for OH were compared with YH.

P = 0.0063 for OH were compared with YH.

P = 0.03 for CAP expression compared with OH.

P = 0.07 for CAP expression compared with OH.

P = 0.04 for OH simvastatin compared with OH VC.

To determine if CD11a expression was associated with migratory accuracy, relationships between expression and migratory accuracy (chemotaxis) were explored. There was a negative correlation between CD11a expression and neutrophil migratory accuracy (Spearman’s correlation, −0.69; P = 0.03) in cells from OH that was not seen when CD11a expression was compared with the migratory accuracy of neutrophils from YH (n = 10 in each group; Spearman’s correlation, 0.28; P = 0.43). The negative correlation between CD11a expression and neutrophil migratory accuracy was no longer present when OH whole blood was treated with simvastatin in vitro (Spearman’s correlation, −0.26; P = 0.47).

To further assess this relationship, neutrophils from YH or OH (n = 10 in each group) were incubated with the lymphocyte function–associated antigen 1 antagonist BIRT-377 or VC and migrated toward CXCL8 (100 nM). Compared with VC, neutrophils from young adults demonstrated a median reduction in chemotaxis of −47.3% (−4.6 to −71.1; P = 0.006), whereas neutrophils from old adults displayed an increase in chemotaxis (percentage increase, 29.8% [5.4–49.0]; P = 0.03) (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Changes to neutrophil chemotaxis after treatment with a CD11a inhibitor. Peripheral neutrophils were isolated from old (aged >60 yr) and young (aged <35 yr) healthy adults and incubated with 26 nM BIRT-377 or vehicle control (VC) for 40 minutes. Each data point represents a single subject, and the median and interquartile range are shown with error bars. BIRT-377 improved neutrophil migratory accuracy from old participants (P = 0.03) but reduced chemotaxis (P = 0.006) of neutrophils from young participants (n = 10 for each group). Data are shown as VC-treated neutrophils migrating to IL-8 (CXCL8) (VC) or BIRT-377–treated neutrophils migrating to CXCL8 (BIRT-377). Data were analyzed using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

Discussion

We present a substantial and novel body of work demonstrating that neutrophils isolated from old adults with an increasing severity of acute pulmonary infections display a progressive impairment of migratory accuracy. Young adults displayed a different response, with neutrophil migratory accuracy impaired only during severe septic events. Neutrophil migration is associated with protease and reactive oxygen species release (31), and meandering migratory pathways may increase tissue exposure to these injurious proteins (3), potentially increasing inflammatory burden and tissue damage, possibly contributing to end-organ damage. Furthermore, after clinical recovery, neutrophils from older adults did not achieve the migratory accuracy present in healthy age-matched peers. These are cross-sectional data, and although it is possible that neutrophil migratory accuracy declines as the infectious insult progresses within an individual, it is also possible that these patients had poorer neutrophil migratory accuracy prior to their infection. Only prospective studies would be able to differentiate these two possibilities; however, either may have clinical significance because clinical data suggest that older patients with pneumonia experience secondary infections that account for 30% of readmissions (32), and those with a poor immune response on admission have a worse long-term prognosis (33).

In vitro migratory accuracy in neutrophils from old donors was enhanced by simvastatin, but only at higher concentrations. Neutrophil migration could be rescued in vitro by simvastatin during LRTI and CAP, but not during a severe septic event and not in young donors. This might support the use of high-dose simvastatin preemptively or early during an infective insult in the elderly, but it suggests that a lack of efficacy would be seen in patients with established severe sepsis, corroborating data from interventional trials (12). In vitro chemotaxis findings were replicated for fMLP in the interventional trial in OH adults without impeding other vital neutrophil functions, such as phagocytosis and NET release. Neutrophil migratory accuracy toward CXCL8 was also increased in the clinical trial, but this did not reach significance when the P value was corrected for multiple comparisons.

The present study also suggests a mechanism of the effect, that of increasing adhesion marker expression with age and infection, which simvastatin reduced. There was a negative correlation between CD11a expression and neutrophil migratory accuracy to CXCL8 in old adults, and BIRT-377 was able to improve neutrophil chemotaxis in neutrophils from old but not young donors. There is a wealth of data suggesting that adhesion markers are increased in sepsis (34, 35) and that statins can reduce their expression and function (36). However, the present study is the first, to our knowledge, to link the increase in adhesion markers on neutrophils with poor migratory accuracy, as well as to show that statins can reduce expression of adhesion markers during an infection and that inhibiting adhesion marker activity (here via a selective inhibitor) replicates the improvement in neutrophil chemotaxis seen after statin exposure, mechanistically linking these findings.

Certain statins can alter adhesion molecule lymphocyte function–associated antigen 1 (containing CD11a) binding to intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (37), but direct steric hindrance is not the only potential mechanism, because statins have been shown to reduce surface expression of CD11a via small GTPase–dependent mechanisms, with mevalonate reversing these effects (38–40). Small GTPase activity can also be modified by phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling, a pathway already implicated in aberrant migration in the elderly (3). Furthermore, activity of Cdc42, a small GTPase implicated in cell polarization and neutrophil migratory accuracy (41) through adhesion marker activity (42), was recently shown to be increased with age and with diseases associated with aging (43).

There is great interest in repurposing medications in novel settings. The disparity in outcomes of statin studies may reflect there being a therapeutic window of benefit for patients, with this window being influenced by statin dose, participant age, and infection severity. Researchers in one study found benefit in a high-dose statin intervention for patients with moderate-severity sepsis if given early during presentation (44), but investigators in recent interventional studies found no survival benefit in a severe sepsis group that included patients with ARDS (13). Authors of a meta-analysis of statin clinical trials with patients without infection found no improvement in subsequent infection rates after 1 year of statin or placebo use. However, the studies included a wide range of patients and diseases; infection was not the primary outcome; and many used “low” statin doses (45). Authors of a more recent meta-analysis of patients admitted with infections suggested a survival benefit with statins, but only in less severe cases (46). Simvastatin could attenuate lung damage after inhalational injury in mice, but only at high doses (47). In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study, the endotoxin-induced systemic inflammatory response was reduced by preemptive simvastatin 80 mg in humans (48). Thus, our data are consistent with animal and human interventional studies of simvastatin.

This work has limitations. For much of our experimental work, only neutrophil migration was reported. However, the process of cytoskeletal rearrangement required to support migration is fundamental to neutrophil functions, and simvastatin did not have an impact on phagocytosis or NETosis in the clinical trial with healthy elders, suggesting these vital neutrophil functions would not be compromised with statin treatment. Studies of neutrophil function with statin exposure in patients with infection were done in vitro and need confirmation in clinical trials. Furthermore, prospective studies in at-risk populations would be needed to confirm whether reduced neutrophil migratory accuracy precedes or is a feature of infection in the elderly. Most studies were conducted using one or two chemoattractants, which does not reflect the inflammatory milieu of biological fluids; however, migration studies were repeated using neutrophils from donors with CAP migrating toward CAP sputum, yielding consistent findings. In our studies, we used the previously globally accepted definition of sepsis (22), and patient groups were maintained using these definitions to allow comparison with results in the published literature; however, when the newly suggested definitions (25) were applied, all patients with sepsis would still be considered as such. Chemokine receptors were not measured on neutrophils during infectious episodes, and although these do not appear to be altered with age in health (3), we cannot exclude changes in expression as contributing to the reduction in chemotaxis. Neutrophil chemotaxis values to BIRT-377 were lower than measured elsewhere in this body of work, which is likely to reflect the use of ethanol as an initial diluent for this compound and the associated VC, but the use of this inhibitor was still able to improve migratory accuracy to CXCL8 in cells from old adults and thus is in keeping with our proposed hypothesis.

Conclusions

Neutrophil migratory accuracy is reduced in old patients with respiratory infections, and this decline in migratory accuracy is worse with worsening infection severity and does not improve 6 weeks after the initial event. Simvastatin can improve migratory accuracy in clinical trials in the healthy elderly and (in vitro) in old patients with mild to moderate infections, but not in the setting of a severe septic event or at low dose. The mechanism of the migratory defect relates in part to increased adhesion molecule expression, which simvastatin normalized in vitro.

Statins do not appear to improve survival in severe sepsis and ARDS. However, our studies would support a randomized clinical trial with older patients with pneumonia but without severe sepsis (a less severe clinical group than has been studied before) because in vitro studies show evidence of benefit.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank staff at the Lung Investigation Unit for help with subject recruitment and characterization and staff at the National Institute for Health Research/Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility for help with the trial protocol and delivery.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the University Hospital Birmingham Charities, the British Lung Foundation, the Medical Research Council, the National Institute of Academic Anaesthesia, and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

Author Contributions: E.S.: designed the studies, recruited patients, undertook laboratory assays, analyzed results, and prepared the manuscript; H.L.G. and J.M.P.: undertook laboratory assays, analyzed results, and helped prepare the manuscript; J.M.P., D.P., and R.C.A.D.: helped with patient recruitment; G.M.W., C.S., and J.H.: performed experimental assays; P.N.: assisted with statistical analysis; J.M.L. and D.R.T.: designed the studies and oversaw manuscript preparation.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201704-0814OC on June 28, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB. Association of diagnostic coding with trends in hospitalizations and mortality of patients with pneumonia, 2003-2009. JAMA. 2012;307:1405–1413. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gavazzi G, Krause KH. Ageing and infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:659–666. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sapey E, Greenwood H, Walton G, Mann E, Love A, Aaronson N, Insall RH, Stockley RA, Lord JM. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition restores neutrophil accuracy in the elderly: toward targeted treatments for immunosenescence. Blood. 2014;123:239–248. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-519520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butcher SK, Chahal H, Lord JM. The effect of age on neutrophil function; loss of CD16 associated with reduced phagocytic capacity [abstract] Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hazeldine J, Harris P, Chapple IL, Grant M, Greenwood H, Livesey A, Sapey E, Lord JM. Impaired neutrophil extracellular trap formation: a novel defect in the innate immune system of aged individuals. Aging Cell. 2014;13:690–698. doi: 10.1111/acel.12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butcher SK, Killampalli V, Chahal H, Kaya Alpar E, Lord JM. Effect of age on susceptibility to post-traumatic infection in the elderly. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:449–451. doi: 10.1042/bst0310449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dremsizov T, Clermont G, Kellum JA, Kalassian KG, Fine MJ, Angus DC. Severe sepsis in community-acquired pneumonia: when does it happen, and do systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria help predict course? Chest. 2006;129:968–978. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.4.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arraes SMA, Freitas MS, da Silva SV, de Paula Neto HA, Alves-Filho JC, Auxiliadora Martins M, Basile-Filho A, Tavares-Murta BM, Barja-Fidalgo C, Cunha FQ. Impaired neutrophil chemotaxis in sepsis associates with GRK expression and inhibition of actin assembly and tyrosine phosphorylation. Blood. 2006;108:2906–2913. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kellum JA, Kong L, Fink MP, Weissfeld LA, Yealy DM, Pinsky MR, Fine J, Krichevsky A, Delude RL, Angus DC GenIMS Investigators. Understanding the inflammatory cytokine response in pneumonia and sepsis: results of the Genetic and Inflammatory Markers of Sepsis (GenIMS) Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1655–1663. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Vught LA, Klein Klouwenberg PM, Spitoni C, Scicluna BP, Wiewel MA, Horn J, Schultz MJ, Nürnberg P, Bonten MJ, Cremer OL, et al. MARS Consortium. Incidence, risk factors, and attributable mortality of secondary infections in the intensive care unit after admission for sepsis. JAMA. 2016;315:1469–1479. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juss JK, House D, Amour A, Begg M, Herre J, Storisteanu DM, Hoenderdos K, Bradley G, Lennon M, Summers C, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome neutrophils have a distinct phenotype and are resistant to phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:961–973. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201509-1818OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mansur A, Steinau M, Popov AF, Ghadimi M, Beissbarth T, Bauer M, Hinz J. Impact of statin therapy on mortality in patients with sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) depends on ARDS severity: a prospective observational cohort study. BMC Med. 2015;13:128. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0368-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catron DM, Lange Y, Borensztajn J, Sylvester MD, Jones BD, Haldar K. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium requires nonsterol precursors of the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway for intracellular proliferation. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1036–1042. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.2.1036-1042.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ARDS Clinical Trials Network. Rosuvastatin for sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2191–2200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chow OA, von Köckritz-Blickwede M, Bright AT, Hensler ME, Zinkernagel AS, Cogen AL, Gallo RL, Monestier M, Wang Y, Glass CK, et al. Statins enhance formation of phagocyte extracellular traps. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walton GM, Stockley JA, Griffiths D, Sadhra CS, Purvis T, Sapey E. Repurposing treatments to enhance innate immunity: can statins improve neutrophil functions and clinical outcomes in COPD? J Clin Med. 2016;5:E89. doi: 10.3390/jcm5100089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chello M, Mastroroberto P, Patti G, D’Ambrosio A, Morichetti MC, Di Sciascio G, Covino E. Simvastatin attenuates leucocyte–endothelial interactions after coronary revascularisation with cardiopulmonary bypass. Heart. 2003;89:538–543. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.5.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nupponen I, Andersson S, Järvenpää AL, Kautiainen H, Repo H. Neutrophil CD11b expression and circulating interleukin-8 as diagnostic markers for early-onset neonatal sepsis. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E12. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller-Kobold AC, Tulleken JE, Zijlstra JG, Sluiter W, Hermans J, Kallenberg CG, Tervaert JW. Leukocyte activation in sepsis; correlations with disease state and mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:883–892. doi: 10.1007/s001340051277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institutes of Health ClinicalTrials.gov[accessed 2017 Mar 27]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=&term=statin+inflammation&cntry1=&state1=&Search=Search

- 21.Sapey E, Greenwood HL, Patel J, Walton GM, Griffiths D, Gao-Smith F, Lord JM.Thickett D. Simvastatin improves outcomes in pneumonia by modulating neutrophil function, but in-vitro and in-vivo studies suggest pre-emptive/early therapy in the elderly [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014189A3978 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Douglas IS, Jaeschke R, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including The Pediatric Subgroup. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:165–228. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim WS, Baudouin SV, George RC, Hill AT, Jamieson C, Le Jeune I, Macfarlane JT, Read RC, Roberts HJ, Levy ML, et al. Pneumonia Guidelines Committee of the BTS Standards of Care Committee. BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax. 2009;64(Suppl 3):iii1–iii55. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.121434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myint PK, Kamath AV, Vowler SL, Maisey DN, Harrison BD. The CURB (confusion, urea, respiratory rate and blood pressure) criteria in community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in hospitalised elderly patients aged 65 years and over: a prospective observational cohort study. Age Ageing. 2005;34:75–77. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stone H, McNab G, Wood AM, Stockley RA, Sapey E. Variability of sputum inflammatory mediators in COPD and α1-antitrypsin deficiency. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:561–569. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00162811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corsini A, Bellosta S, Baetta R, Fumagalli R, Paoletti R, Bernini F. New insights into the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of statins. Pharmacol Ther. 1999;84:413–428. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly TA, Jeanfavre DD, McNeil DW, Woska JR, Jr, Reilly PL, Mainolfi EA, Kishimoto KM, Nabozny GH, Zinter R, Bormann BJ, et al. Cutting edge: a small molecule antagonist of LFA-1-mediated cell adhesion. J Immunol. 1999;163:5173–5177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muinonen-Martin AJ, Veltman DM, Kalna G, Insall RH. An improved chamber for direct visualisation of chemotaxis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mortensen EM, Restrepo MI, Anzueto A, Pugh J. The effect of prior statin use on 30-day mortality for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Respir Res. 2005;6:82. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cepinskas G, Sandig M, Kvietys PR. PAF-induced elastase-dependent neutrophil transendothelial migration is associated with the mobilization of elastase to the neutrophil surface and localization to the migrating front. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:1937–1945. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.12.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Alba I, Amin A. Pneumonia readmissions: risk factors and implications. Ochsner J. 2014;14:649–654. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guertler C, Wirz B, Christ-Crain M, Zimmerli W, Mueller B, Schuetz P. Inflammatory responses predict long-term mortality risk in community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:1439–1446. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00121510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller Kobold AC, Mesander G, Stegeman CA, Kallenberg CG, Tervaert JW. Are circulating neutrophils intravascularly activated in patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides? Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:491–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zonneveld R, Martinelli R, Shapiro NI, Kuijpers TW, Plötz FB, Carman CV. Soluble adhesion molecules as markers for sepsis and the potential pathophysiological discrepancy in neonates, children and adults. Crit Care. 2014;18:204. doi: 10.1186/cc13733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenwood J, Steinman L, Zamvil SS. Statin therapy and autoimmunity: from protein prenylation to immunomodulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:358–370. doi: 10.1038/nri1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weitz-Schmidt G, Welzenbach K, Brinkmann V, Kamata T, Kallen J, Bruns C, Cottens S, Takada Y, Hommel U. Statins selectively inhibit leukocyte function antigen-1 by binding to a novel regulatory integrin site. Nat Med. 2001;7:687–692. doi: 10.1038/89058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rezaie-Majd A, Prager GW, Bucek RA, Schernthaner GH, Maca T, Kress HG, Valent P, Binder BR, Minar E, Baghestanian M. Simvastatin reduces the expression of adhesion molecules in circulating monocytes from hypercholesterolemic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:397–403. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000059384.34874.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weber C, Erl W, Weber KS, Weber PC. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors decrease CD11b expression and CD11b-dependent adhesion of monocytes to endothelium and reduce increased adhesiveness of monocytes isolated from patients with hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1212–1217. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshida M, Sawada T, Ishii H, Gerszten RE, Rosenzweig A, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Yasukochi Y, Numano F. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor modulates monocyte–endothelial cell interaction under physiological flow conditions in vitro: involvement of Rho GTPase–dependent mechanism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1165–1171. doi: 10.1161/hq0701.092143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang HW, Collins SR, Meyer T. Locally excitable Cdc42 signals steer cells during chemotaxis. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:191–201. doi: 10.1038/ncb3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar S, Xu J, Perkins C, Guo F, Snapper S, Finkelman FD, Zheng Y, Filippi MD. Cdc42 regulates neutrophil migration via crosstalk between WASp, CD11b, and microtubules. Blood. 2012;120:3563–3574. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-426981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Florian MC, Klenk J, Marka G, Soller K, Kiryakos H, Peter R, Herbolsheimer F, Rothenbacher D, Denkinger M, Geiger H. Expression and activity of the small RhoGTPase Cdc42 in blood cells of older adults are associated with age and cardiovascular disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72:1196–1200. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel JM, Snaith C, Thickett D, Linhortova L, Melody T, Hawkey P, Barnett T, Jones A, Hong T, Perkins G, et al. Atorvastatin for preventing the progression of sepsis to severe sepsis (ASEPSIS Trial): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (ISRCTN64637517) [abstract] Crit Care. 2011;15(Suppl 1):P268. doi: 10.1186/cc11895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van den Hoek HL, Bos WJW, de Boer A, van de Garde EMW. Statins and prevention of infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of data from large randomised placebo controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d7281. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jia M, Huang W, Li L, Xu Z, Wu L. Statins reduce mortality after non-severe pneumonia but not after severe pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;18:286–302. doi: 10.18433/j34307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobson JR, Barnard JW, Grigoryev DN, Ma SF, Tuder RM, Garcia JGN. Simvastatin attenuates vascular leak and inflammation in murine inflammatory lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L1026–L1032. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00354.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steiner S, Speidl WS, Pleiner J, Seidinger D, Zorn G, Kaun C, Wojta J, Huber K, Minar E, Wolzt M, et al. Simvastatin blunts endotoxin-induced tissue factor in vivo. Circulation. 2005;111:1841–1846. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158665.27783.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]