Abstract

Objectives

Antenatal care (ANC) is an essential part of primary healthcare and its provision has expanded worldwide. There is limited evidence of large-scale cross-country studies on the impact of ANC offered to pregnant women on child health outcomes. We investigate the association of ANC in low-income and middle-income countries with short- and long-term mortality and nutritional child outcomes.

Setting

We used nationally representative health and welfare data from 193 Demographic and Health Surveys conducted between 1990 and 2013 from 69 low-income and middle-income countries for women of reproductive age (15–49 years), their children and their respective household.

Participants

The analytical sample consisted of 752 635 observations for neonatal mortality, 574 675 observations for infant mortality, 400 426 observations for low birth weight, 501 484 observations for stunting and 512 424 observations for underweight.

Main outcomes and measures

Outcome variables are neonatal and infant mortality, low birth weight, stunting and underweight.

Results

At least one ANC visit was associated with a 1.04% points reduced probability of neonatal mortality and a 1.07% points lower probability of infant mortality. Having at least four ANC visits and having at least once seen a skilled provider reduced the probability by an additional 0.56% and 0.42% points, respectively. At least one ANC visit is associated with a 3.82% points reduced probability of giving birth to a low birth weight baby and a 4.11 and 3.26% points reduced stunting and underweight probability. Having at least four ANC visits and at least once seen a skilled provider reduced the probability by an additional 2.83%, 1.41% and 1.90% points, respectively.

Conclusions

The currently existing and accessed ANC services in low-income and middle-income countries are directly associated with improved birth outcomes and longer-term reductions of child mortality and malnourishment.

Keywords: epidemiology, perinatology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study on the association of antenatal care (ANC) with child health and vital outcomes for all low-income and middle-income countries for which high-quality and comparable data are available.

This is the first study investigating the possible long-term effects of the utilisation of ANC on children’s nutritional and vital status.

The study focuses on the association between the ANC services effectively available and accessible to women in low-income and middle-income countries and hence, generates knowledge on the current status quo and effect of the ANC services on child health.

The analysis does not allow a causal interpretation of the results.

Data availability limits the investigation of the association of more disaggregated quality indicators of ANC with the outcome variables.

Introduction

Despite strong international efforts to expand the worldwide coverage of basic primary health services for women, pregnancy and childbirth still represent a high-risk period for mother and child; especially in low-income and middle-income countries. Reductions in maternal and early child mortality remain high on the global development policy agenda, which can be seen in its inclusion in the Sustainabile Development Goal 3.1 However, nearly 3 million babies die every year during their first month of life, and in low-income and middle-income countries, many of those deaths and morbidities are due to easily preventable causes.2 3 Undetected infections during pregnancy, such as malaria, syphilis, tuberculosis, tetanus or HIV/AIDS, as well as high blood pressure, diabetes and other pre-existing health conditions often complicate or aggravate pregnancy and pose significant risk for mother and child. Antenatal care (ANC)—the services offered to mother and unborn child during pregnancy—is an essential part of basic primary healthcare during pregnancy, and offers a mosaic of services that can prevent, detect and treat risk factors early on in the pregnancy. The detection of high-risk pregnancies through the analysis of socioeconomic, medical and obstetrical factors represents a key element of ANC. It is also often used as a platform for additional interventions that have been shown to positively influence the maternal and child health status, such as immunisation and nutrition programmes and breastfeeding counselling, or to educate women about the possibilities of family planning and birth spacing.4–13 In addition, ANC programmes are used to provide care and information that is not directly related to pregnancy but can reduce the possible maternal risk factors, such as promoting healthy lifestyles, tackle malnutrition or inform about gender-based violence. Hence, ANC is a potentially important determinant in reducing maternal and child morbidity and mortality.14–22

Within the last decades, the provision of ANC services has increased worldwide. During 2010–2015, the ANC coverage, defined as the percentage of women aged 15–49 years who attended at least one ANC visit with a skilled provider, was around 85% globally and approximately 77% in the least developed countries.23 24 To our knowledge, there exists no global study for all low-income and middle-income countries, which analyses the association of existing ANC services that are offered to pregnant women in low-income and middle-income countries on child health outcomes.

Numerous studies have helped to develop an internationally accepted set of so-called essential ANC services by evaluating the effects of single interventions, such as tetanus and malaria prevention programmes, on maternal and neonatal health25–30 or by studying the optimal number and content of ANC visits.31–34 However, the de facto offered and used set of ANC services can deviate greatly from the recommended ANC interventions. A couple of studies evaluate the relationship between the utilisation of ANC services and perinatal outcomes in individual low-income and middle-income countries. The majority have shown the positive effects of ANC on newborn mortality, the occurrence of stillbirth and preterm labour and low birth weight.35–43 However, they exclusively focus on single countries, are often conducted at the clinic level and have small sample sizes. This limits their external validity. We identified only one study that focuses on a larger regional sample. Conde-Agudelo et al studied 837 232 births in Latin America between 1985 and 1997.44 One major risk factor associated with fetal death was the lack of ANC. We could not find a study that took into account the possible long-term effects of the utilisation of ANC services on children’s nutritional and vital status.

With up to 193 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) from 69 low-income and middle-income countries, we use the most comprehensive data for low-income and middle-income countries that currently exist. Specifically, we investigate whether the attendance of mothers at ANC services was associated with improved short-term and long-term survival rates or reductions in the prevalence of low birth weight, stunting and underweight in their children.

Methods

Data

We used data from the DHS, which are publicly available online (http://dhsprogram.com). The DHS are cross-sectional household surveys that use a harmonised questionnaire to facilitate between-country comparisons. The DHS collect nationally representative health and welfare data for women of reproductive age (15–49 years), their children and their respective household.

They have been conducted at different time intervals in 90 low-income and middle-income countries since 1985. We included all surveys, which have information for the relevant outcome and explanatory variables. The final sample consists of pooled data from up to 193 surveys in 69 low-income and middle-income countries worldwide, conducted between 1 January 1990 and 31 December 2013. The DHS used a multistage stratified sampling. Countries were divided into regions, within which populations were stratified by area of residence and from which a random sample was taken according to the most recent population census. Those are the primary sampling units (clusters with an average of 250 households), which are equally likely to be selected to the proportion of the specific cluster’s population that contributed to the total population. At the second stage, after a complete listing of all households within the cluster, an average of 20–30 households were randomly selected by equal probability. Sampling weights in order to calculate nationally representative statistics are provided by the DHS.

Women were, among other things, asked for each live birth within 5 (or in some cases 3) years prior to the survey about date of birth, birth weight, vital status at the time of the interview and either current age or age at death of the child. Furthermore, the DHS collected information on the height and weight of the children born during the last 3 or 5 years.

For each last-born live birth of the previous 3 or 5 years, there is information on the attendance rates and quality of ANC visits during the last pregnancy that led to a live birth. Considering the ongoing debates on the importance of the quality and number of ANC visits,31 45–48 we specified two different main explanatory variables. First, the mere attendance of ANC (a dummy variable indicating whether the woman attended at least one ANC visit during her last pregnancy leading to a live birth) irrespective of the total number of visits and the type of provider. To proxy WHOrecommendations regarding prenatal care (at least four visits at a skilled provider1), we specified a variable indicating whether the woman saw at least once a skilled provider during her at least four ANC visits. Unfortunately, we were unable to identify whether all ANC visits were provided by a skilled professional. ANC visits to a doctor, midwife, nurse, auxiliary midwife, obstetrician, health professional or trained (traditional) birth attendant were considered as skilled ANC services, whereas ANC with a traditional birth attendant, relatives, any other person or none of the mentioned was classified as unskilled ANC.

Outcomes

We analysed the data for short-term and long-term vital outcomes and low birth weight of all last-born live births as well as stunting and underweight for the last-born children aged 0–59 months (in some surveys 0–36 months) at the time of the interview. Hence, each woman is represented only once in the dataset with the information of her last-born child (in case of a live birth). Mortality outcomes were neonatal death, defined as death of a live birth within the first month of life, and infant death, defined as death after the first month but within the first year of life. The latter excludes neonatal deaths and is restricted to children aged at least 1 year. Nutritional outcomes were low birth weight, stunting and underweight. We used WHO classification that defines low birth weight as a birth weight below 2500 g at birth. Following WHO and Unicef suggestions, we only included biologically plausible birth weights from 500 to 5999 g. To calculate stunting and underweight, we used anthropometric data defined by WHO standards and classifications (using the Stata package ‘igrowup_stata’). Comparing the child’s height and weight to those of a well-nourished reference population of the same age and sex allows us to calculate the z-scores of height-for-age and weight-for-age. Stunting is defined by a height-for-age z-score of less than −2, and underweight is defined by a weight-for-age z-score of less than −2. Biologically implausible values of the z-scores were excluded following WHO guidelines.

Statistical analysis

We used linear probability regression models to investigate the association between ANC services and short-term and long-term vital and health outcomes of children. We adjusted the regressions for confounding factors and controlled for primary sampling unit (PSU) fixed effects. The PSU fixed effects are survey specific and herewith, we control for common factors faced by households in the same PSU at one point in time, such as the local availability and quality of health providers and other local factors. SEs were clustered at the PSU level as respondents in the same PSU might experience common shocks. They capture characteristics of local enumeration areas that are common to all respondents from that area. We used sex, birth order (five categories: ranging from ‘first born’ to ‘fifth or later born’ child), birth spacing (five categories: ranging from ‘no preceding birth’ to ‘equal or more than 36 months’), birth month and whether the child was a multiple birth, the mother’s age at birth (five categories: ranging from ‘below 17’ to ‘equal or above 30’ years), education (five categories: ranging from ‘no education’ to ‘higher education’), work status, relation to the household head (dummy indicating whether the mother is the household head) and her marital status and household wealth quintile as covariates. The wealth quintile variable is constructed by using a principal component analysis, is based on the ownership of household assets (eg, electricity, television and quality of dwelling) and indicates the household’s wealth relative to other households within the respective country in that survey. Additionally, by including variables indicating the place of delivery, mode of delivery (vaginal or caesarean), status of tetanus injection of mother before birth and if the mother breastfed at least 1 month after birth (several only applicable for long-term outcomes), we inspected the possible mediator variables, meaning that the uptake of ANC services might starkly influence those variables, which themselves might affect the outcome variables.

Using Stata (V.14.0) for all statistical analyses, we also took into account the stratified survey design by using the Stata svy command. We used sampling weights provided by the DHS in all our regressions.

Results

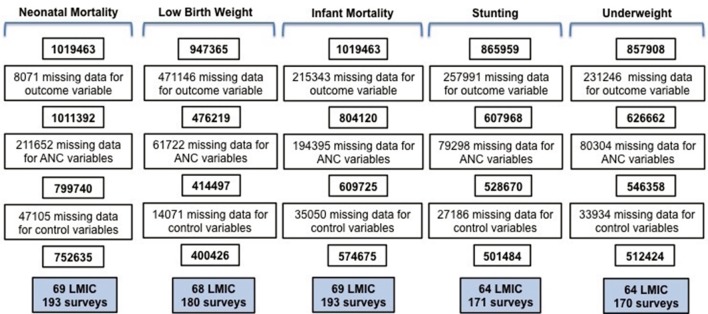

Our initial samples consisted of surveys for which the respective outcome variable and the information on ANC visits were collected and composed children between 0 and 59 months at the time of the interview and who were permanent members of the respective household. The total sample for neonatal and infant mortality included observations for 1 019 463 children. In some survey rounds, data on birth weight and in others on anthropometric measures were not systematically collected. This left us with data of 947 365 children, where information on their birth weight could have potentially been recorded. For stunting, this amounted up to 865 959 children and for underweight to 857 908 children.

Observations were lost due to missing data on outcome variables, missing data on the ANC variables (including the dummies indicating the mere attendance of ANC visits and the attendance of at least four ANC visits while the woman at least once saw a skilled provider) or missing data on covariates. The final analytical sample was 752 635 for neonatal mortality, 400 426 for low birth weight, 574 675 for infant mortality, 501 484 for stunting and 512 424 for underweight (see figure 1 and online supplementary table A1).

Figure 1.

Sample deduction. ANC, antenatal care; LMIC, low-income and middle-income countries.

bmjopen-2017-017122supp001.pdf (467.2KB, pdf)

The prevalence of newborn death was higher among women who did not receive any ANC check-up (3.12%) compared with those attending at least one check-up (1.67%). For infant mortality, the respective numbers are 4.23% and 2.21%. Prevalence of all outcome variables was higher among women not attending any ANC visit than those attending at least one ANC check-up and to those who received at least four ANC visits while at least once having seen a skilled provider (table 1). Pregnant women who did not attend ANC visits were on average less educated and poorer than those women who attended at least one ANC check-up (see online supplementary table A2 appendix).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Outcome variable | Mother attended at least one ANC visit, % (n=616 347) | Mother attended at least four ANC visits and has seen skilled provider, % (n=416 350) | Mother did not attend ANC visit, % (n=136 288) |

| Neonatal mortality | 1.67* | 1.40* | 3.12 |

| Infant mortality | 2.21* | 1.81* | 4.23 |

| Low birth weight | 9.69* | 8.94* | 14.35 |

| Stunting | 31.35* | 27.18* | 47.08 |

| Underweight | 15.70* | 12.02* | 30.72 |

n Values denote the number of observations in the neonatal mortality sample.

*Proportions to the group ‘mother did not attend ANC visit’ were significantly different from each other, p≤0.05 (Student’s t-test).

ANC, antenatal care.

In table 2, we report the association between ANC take-up and short-term and long-term mortality outcomes. For each outcome, we show the results from three different specifications where PSU fixed effects are included in all three. The first column shows the mere association between the attendance of at least one ANC visit without controlling for any covariates. The second column shows the association adjusted for control variables, and the third column reports the coefficients while adding whether the mother has received at least four ANC visits during pregnancy while at least having once seen a skilled provider. The interpretation of this additional term follows the logic of an interaction term as it overlaps in its definition with the variable indicating the mere attendance of ANC. Hence, it shows the additional effect if the mother followed more closely WHO recommendations. In supplementary table A2 and A4 appendix), we report the regression results where in addition to control variables, we also adjusted for potential transmission channels of ANC (place of delivery, mode of delivery, status of tetanus toxoid injection of mother before birth and whether the mother breastfed at least for 1 month after birth). We will focus on the second and third specifications adjusted for control variables and only refer to the other specifications for comparison purposes.

Table 2.

Associations between antenatal care visits and mortality outcomes

| Neonatal mortality | Infant mortality | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| At least one ANC visit | −0.0107*** (0.001) |

−0.0104*** (0.001) | −0.00783*** (0.001) |

−0.0127*** (0.001) | −0.0107*** (0.001) |

−0.00873*** (0.001) |

| At least four ANC visits and skilled ANC provider | −0.00557*** (0.001) | −0.00424*** (0.001) |

||||

| N | 752 635 | 752 635 | 752 635 | 574 675 | 574 675 | 574 675 |

| Adjusted for confounding | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

All regressions include PSU fixed effects.

SEs in parentheses are clustered at PSU level.

Control variables include: mother’s age, marital status and educational achievement, whether she heads the household, child’s sex and birth order and spacing, month of birth, whether it was a multiple birth and household wealth quintile.

***, ** and * Significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

ANC, antenatal care.

Women attending at least one ANC visit have a 1.04% points reduced probability of their newborn dying within the first month after birth and a 1.07% points lower probability of experiencing death of their child within the first year of life. Following the WHO recommendations on ANC visits is significantly related to lower mortality outcomes. Compared with the mere attendance of less than four ANC visits (irrespective of the quality of the provider), having at least four ANC visits and having at least once seen a skilled provider reduce the probability of neonatal deaths by an additional 0.56% points and are associated with an additional 0.42% points reduction in the probability of infant deaths.

The DHS dataset also provides information on several variables that are well-established in the literature to impact mortality and morbidity outcomes of children and that simultaneously are potentially influenced by ANC attendance. When controlling for these potential transmission channels of ANC services, it can be seen that the majority of the ANC coefficients are somewhat attenuated when controlling for these additional variables but not by much (online supplementary table A3). Results for all covariates are provided in online supplementary A5 appendix.

In table 3, we report the association between ANC and short-term and long-term nutritional outcomes of the child. If the mother attends at least one ANC visit, this is associated with a 3.82% points reduced probability of giving birth to a low birth weight baby. Stunting and underweight outcomes are reduced by 4.11% and 3.26% points, respectively. Attendance at a skilled provider during at least one of at least four ANC visits further reduces the probability of having a low birth weight baby by 2.83% points, for stunting by 1.41% points and for underweight by 1.90% points.

Table 3.

Associations between antenatal care visits and nutritional outcomes

| Low birth weight | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| At least one ANC visit | −0.0428***(0.004) | −0.0382*** (0.004) | −0.0187*** (0.004) |

| At least four ANC visits and skilled ANC provider | −0.0283*** (0.002) | ||

| N | 400 426 | 400 426 | 400 426 |

| Stunting | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| At least one ANC visit | −0.0677*** (0.003) | −0.0411*** (0.003) | −0.0345*** (0.003) |

| At least four ANC visits and skilled ANC provider | −0.0141*** (0.002) | ||

| N | 501 484 | 501 484 | 501 484 |

| Underweight | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| At least one ANC visit | −0.0502*** (0.002) | −0.0326*** (0.002) | −0.0237*** (0.002) |

| At least four ANC visits and skilled ANC provider | −0.0190*** (0.002) | ||

| N | 512 424 | 512 424 | 512 424 |

| Adjusted for confounding | No | Yes | Yes |

All regressions include PSU fixed effects.

SEs in parentheses are clustered at PSU level.

Control variables include: mother’s age, marital status and educational achievement, whether she heads the household, child’s sex and birth order and spacing, month of birth, whether it was a multiple birth and household wealth quintile.

***, ** and *Significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

ANC, antenatal care.

Adding potential transmission channels of ANC services to the regression slightly attenuates the ANC coefficients in case of low birth weight and underweight (online supplementary table A4). Results for all covariates are provided in online supplementary table A5.

Discussion

Most existing evidence on the effect of ANC on child health is based on data from high-income countries, and their conclusions are not easily transferable to low-income and middle-income settings. The existing studies for low-income and middle-income countries often focus on individual countries. Furthermore, the studied effects of ANC have been limited to direct short-term maternal and child delivery outcomes. This is the first large-scale cross-country study for all low-income and middle-income countries with available comparable data for ANC, which systematically investigates the association of ANC with short-term and long-term mortality and nutritional child outcomes.

Using child vital data and child anthropometry from up to 193 surveys in 69 low-income and middle-income countries, we have shown that ANC is associated with reductions in neonatal and infant mortality, low birth weight, stunting and underweight. While we measure the average effects across countries and years, we find that this association remains relatively stable across survey rounds (online supplementary table A6) and can be seen for all outcomes in almost all world regions (online supplementary figures A1 and A2); though it is especially strong in Latin America and Caribbean, Sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southeast Asia (which constitute about 90% of our sample). Receiving prenatal care by skilled providers and attending at least four ANC visits is significantly associated with additional prevalence reductions of all outcome variables and hence, plays an important role in the provision of ANC services. The magnitude of the association is quantitatively important, as it varies around −1.04% and −4.11% points.

Many pregnant women in low-income and middle-income countries have no access to or do not attend ANC services regularly enough (more than four visits) and many do not see a skilled provider.23 49 50 According to our results, improving the coverage and uptake of ANC services could be an important tool to improve short-term and even long-term mortality and nutritional outcomes of children.

There are a couple of self-selection issues and limitations that we have attempted to address. Unfortunately, we do not have disaggregated information on the type of provider (skilled/unskilled) for each ANC visit. We try to proxy this by including whether the woman has at least once seen a skilled provider during her pregnancy. Furthermore, we controlled for mother’s education and household wealth, since more educated or more affluent mothers might be more likely to seek ANC and at the same time have a better overall health status. Similarly, we adjusted for PSU fixed effects to control for community characteristics, overall health status in the region and the local availability and quality of healthcare services as well as other characteristics that are common to the local area. However, there are a few maternal characteristics, which we did not observe and therefore were not able to control for. For instance, if pregnant women feel that there could be something wrong, they might be more likely to seek ANC. Similarly, if women had negative birth outcomes in the past, they might also be more likely to seek ANC to avoid the repetition of the negative birth outcome. Both cases would downward bias our estimates and the true association would be even stronger than the association, which we found in our analysis. It is important to point out again that we are only including the outcomes of live births. The attendance at ANC services might lead to better survival chances of those babies that would have otherwise died before birth. This might impose a downward bias on our estimates. However, there are also potential selection issues, which could bias the results in the other direction. For instance, it is unclear how women would behave in case of an unwanted pregnancy. They might be less likely to seek ANC and have worse overall health behaviour compared with women in planned pregnancies. In a robustness check, we controlled for an indicator variable if the pregnancy was wanted, and this did not change the results. Additionally, we cannot further approximate the quality of care received by the women. As the quality of care will influence the effect of ANC, this limits our study. By including PSU level fixed effects, we absorb indicators that are similar across this geographical unit and survey. Assuming that the quality of ANC available to women within the same PSU is comparable, we successfully address this data limitation. We also assume that missing data in our sample was not systematically correlated with the true unobserved child health and vital outcomes and the availability and accessibility of ANC services.

In summary, our study provides evidence for the potential importance of ANC for improving child health and vital outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries and might be an important tool to reach the third Sustainable Development Goal by 2030.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

None

Footnotes

In 2016, WHO updated their recommendations to at least eight prenatal care visits at skilled providers.51

Contributors: JK and SV conceptualised the study, developed the analytical strategy and interpreted the data. JK conducted the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SV critically revised the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Procedures and questionnaires for standard DHS surveys have been approved by the ICF Institutional Review Board (IRB) and by the relevant body in each country. ICF IRB ensures that the survey complies with the US Department of Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human subjects (45 CFR 46), while the host country IRB ensures that the survey complies with laws and norms of the nation.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This study used data that was collected by the Demographic and Health Surveys Program (www.dhsprogram.com), under a contract from the US Agency for International Development.

References

- 1.UN Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 3: ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. United Nations Sustainable Development Home page; 2017. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/ (accessed Aug 12 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO. Global Health Observatory (GHO) data: Neonatal Mortality. World Health Organization. 2017. http://www.who.int/gho/child_health/mortality/neonatal_text/en/ (accessed 12 Aug 2017).

- 3. UNICEF. Committing to child survival: a promise renewed. Progress report 2015. United Nations Children’s Fund. 2015.

- 4. Imdad A, Bhutta ZA. Effects of calcium supplementation during pregnancy on maternal, fetal and birth outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012;26 Suppl 1:138–52. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gupta A. Breastfeeding and child health. Economic and Political Weekly 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oddy WH, Kendall GE, Li J, et al. . The long-term effects of breastfeeding on child and adolescent mental health: a pregnancy cohort study followed for 14 years. J Pediatr 2010;156:568–74. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, et al. . Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013;382:427–51. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Titaley CR, Dibley MJ. Antenatal iron/folic acid supplements, but not postnatal care, prevents neonatal deaths in Indonesia: analysis of Indonesia demographic and health surveys 2002/2003-2007 (a retrospective cohort study). BMJ Open 2012;2:e001399 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ota E, Hori H, Mori R, et al. . Antenatal dietary education and supplementation to increase energy and protein intake. Cochrane Database Systematic Review. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10. Pena-Rosas JP, De-Regil LM, Garcia-Casal MN, et al. . Daily oral iron supplementation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Systematic Review. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11. Haider BA, Bhutta ZA. Multiple-micronutrient supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Systematic Review 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Jongh TE, Gurol-Urganci I, Allen E, et al. . Integration of antenatal care services with health programmes in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review. J Glob Health 2016;6:010403 10.7189/jogh.06.010403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McNellan CR, Dansereau E, Colombara D, et al. . Uptake of antenatal care, and its relationship with participation in health services and behaviors: an analysis of the poorest regions of four Mesoamerican countries. Ann Glob Health 2017;83:193–4. 10.1016/j.aogh.2017.03.482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carroli G, Rooney C, Villar J. How effective is antenatal care in preventing maternal mortality and serious morbidity? An overview of the evidence. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2001;15 Suppl 1:1–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abou-Zahr C, Wardlaw T. Antenatal care in developing countries: promises, achievements and missed opportunities. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen XK, Wen SW, Yang Q, et al. . Adequacy of prenatal care and neonatal mortality in infants born to mothers with and without antenatal high-risk conditions. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2007;47:122–7. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00697.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. . WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet 2006;367:1066–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68397-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lincetto O, Mothebesoane-Anoh S, Gomez P, et al. . In opportunties for Africa’s newborns. PMNCH 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organization. WHO statement on antenatal care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zanconato G, Msolomba R, Guarenti L, et al. . Antenatal care in developing countries: the need for a tailored model. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2006;11:15–20. 10.1016/j.siny.2005.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. PMNCH. The PMNCH Report 2012. Analysing Progress on Commitments to the Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moss W, Darmstadt GL, Marsh DR, et al. . Research priorities for the reduction of perinatal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in developing country communities. J Perinatol 2002;22:484–95. 10.1038/sj.jp.7210743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. UNICEF. UNICEF data: monitoring the situation of children and women. UNICEF 2017. https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/antenatal-care/# (accessed 12 Aug 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang W, Alva S, Wang S, et al. . Levels and trends in the use of maternal health services in developing countries. DHS comparative reports No. 26 Calverton, Maryland, USA: ICF Macro. 2011.

- 25. Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Bahl R, et al. . Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? Lancet 2014;384:347–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60792-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Blencowe H, Lawn J, Vandelaer J, et al. . Tetanus toxoid immunization to reduce mortality from neonatal tetanus. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:i102–i109. 10.1093/ije/dyq027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Demicheli V, Barale A, Rivetti A. Vaccines for women for preventing neonatal tetanus. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Kamb M, et al. . Lives saved tool supplement detection and treatment of syphilis in pregnancy to reduce syphilis related stillbirths and neonatal mortality. BMC Public Health 2011;11:S9 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kayentao K, Garner P, van Eijk AM, et al. . Intermittent preventive therapy for malaria during pregnancy using 2 vs 3 or more doses of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and risk of low birth weight in Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2013;309:594–604. 10.1001/jama.2012.216231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Althabe F, Belizán JM, McClure EM, et al. . A population-based, multifaceted strategy to implement antenatal corticosteroid treatment versus standard care for the reduction of neonatal mortality due to preterm birth in low-income and middle-income countries: the ACT cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2015;385:629–39. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61651-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Villar J, Ba’aqeel H, Piaggio G, et al. . WHO antenatal care randomised trial for the evaluation of a new model of routine antenatal care. Lancet 2001;357:1551–64. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04722-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Carroli G, Villar J, Piaggio G, et al. . WHO systematic review of randomised controlled trials of routine antenatal care. Lancet 2001;357:1565–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04723-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lavin T, Pattinson RC. Does antenatal care timing influence stillbirth risk in the third trimester? A secondary analysis of perinatal death audit data in South Africa. BJOG 2017. 10.1111/1471-0528.14645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nimi T, Fraga S, Costa D, et al. . Prenatal care and pregnancy outcomes: a cross-sectional study in Luanda, Angola. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016;135:S72–S78. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hong R, Ruiz-Beltran M. Impact of prenatal care on infant survival in Bangladesh. Matern Child Health J 2007;11:199–206. 10.1007/s10995-006-0147-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kapoor SK, Anand K, Kumar G. Risk factors for stillbirths in a secondary level hospital at Ballabgarh, Haryana: a case control study. Indian J Pediatr 1994;61:161–6. 10.1007/BF02843608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mbuagbaw LC, Gofin R. A new measurement for optimal antenatal care: determinants and outcomes in Cameroon. Matern Child Health J 2011;15:1427–34. 10.1007/s10995-010-0707-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brown CA, Sohani SB, Khan K, et al. . Antenatal care and perinatal outcomes in Kwale district, Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2008;8:2 10.1186/1471-2393-8-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Celik Y, Younis MZ. Effects of antenatal care services on birthweight: importance of model specification and empirical procedure used in estimating the marginal productivity of health inputs. J Med Syst 2007;31:197–204. 10.1007/s10916-007-9055-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McCaw-Binns A, Greenwood R, Ashley D, et al. . Antenatal and perinatal care in Jamaica: do they reduce perinatal death rates? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1994;8:86–97. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1994.tb00493.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Barbosa IR, Silva WB, Cerqueira GS, et al. . Maternal and fetal outcome in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: the impact of prenatal care. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis 2015;9:140–6. 10.1177/1753944715597622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Abbas AM, Rabeea M, Abdel Hafiz HA, et al. . Effects of irregular antenatal care attendance in primiparas on the perinatal outcomes: a cross sectional study. Proceedings in Obstetrics and Gynecology. In Press 2017;3. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ballard K, Belete Z, Kinfu H, et al. . The effect of prenatal and intrapartum care on the stillbirth rate among women in rural Ethiopia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016;133:164–7. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Conde-Agudelo A, Belizán JM, Díaz-Rossello JL. Epidemiology of fetal death in Latin America. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79:371–8. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2000.079005371.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vogel JP, Habib NA, Souza JP, et al. . Antenatal care packages with reduced visits and perinatal mortality: a secondary analysis of the WHO Antenatal care trial. Reprod Health 2013;10:19 10.1186/1742-4755-10-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. . Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD000934 10.1002/14651858.CD000934.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hofmeyr GJ, Hodnett ED. Antenatal care packages with reduced visits and perinatal mortality: a secondary analysis of the WHO antenatal care trial - Comentary: routine antenatal visits for healthy pregnant women do make a difference. Reprod Health 2013;10:20 10.1186/1742-4755-10-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hodgins S, D’Agostino A. The quality-coverage gap in antenatal care: toward better measurement of effective coverage. Glob Health Sci Pract 2014;2:173–81. 10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. You D, Hug L, Ejdmeyr S, et al. . Levels and Trends in Child Mortality. Report. New York, USA: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 50. World Health Organization. World Health Statistics. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 51. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017122supp001.pdf (467.2KB, pdf)