Abstract

Introduction

Based on epidemiological, immunological and pathology data, the idea that appendicitis is not necessarily a progressive disease is gaining ground. Two types are distinguished: simple and complicated appendicitis. Non-operative treatment (NOT) of children with simple appendicitis has been investigated in several small studies. So far, it is deemed safe. However, its effectiveness and effect on quality of life (QoL) have yet to be established in an adequately powered randomised trial. In this article, we provide the study protocol for the APAC (Antibiotics versus Primary Appendectomy in Children) trial.

Methods and analysis

This multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial randomises children aged 7–17 years with imaging-confirmed simple appendicitis between appendectomy and NOT. Patients are recruited in 15 hospitals. The intended sample size, based on the primary outcome, rate of complications and a non-inferiority margin of 5%, is 334 patients.

NOT consists of intravenous antibiotics for 48–72 hours, daily blood tests and ultrasound follow-up. If the patient meets the predefined discharge criteria, antibiotic treatment is continued orally at home. Primary outcome is the rate of complications at 1-year follow-up. An independent adjudication committee will assess all complications and their relation to the allocated treatment. Secondary outcomes include, but are not limited to, delayed appendectomies, QoL, pain and (in)direct costs.

The primary outcome will be analysed both according to the intention-to-treat principle and the per-protocol principle, and is presented with a one-sided 97.5% CI. We will use multiple logistic and linear regression for binary and continuous outcomes, respectively, to adjust for stratification factors.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol has been approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee of the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam. Data monitoring is performed by an independent institute and a Data Safety Monitoring Board has been assigned. Results will be presented in peer-reviewed academic journals and at (international) conferences.

Trial registration number

Keywords: paediatrics, paediatric gastroenterology, paediatric surgery, paediatric colorectal surgery, surgery

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Meticulous selection of children with uncomplicated appendicitis using strict (evidence-based) criteria, including ultrasonography.

Elaborate follow-up on patient, parent, hospital and economic levels.

An independent adjudication committee assessing all complications and their relation to the allocated treatment.

The non-inferiority design does not allow for a superiority comparison of the rate of complications.

Introduction

Appendicitis is a common gastrointestinal disease with a lifetime incidence of 7%–9%.1 2 Based on the assumption that urgent removal of the appendix is necessary to avoid progressive inflammation with subsequent necrosis and perforation of the appendix, emergency appendectomy has been the standard of care since 1889. However, based on epidemiological, immunological and pathology data, several experts have stated3–6 that appendicitis is not necessarily a progressive disease. Rather, they endorse the idea that two types of appendicitis exist: simple or uncomplicated appendicitis and complicated appendicitis. Over the years, there has been a shift towards non-operative treatment (NOT) strategies for diseases which were historically treated surgically, for instance, stomach ulcers and uncomplicated diverticulitis. More recently, NOT of acute uncomplicated appendicitis (AUA) has become the subject of investigation. This strategy consists of initial treatment with intravenous antibiotics and reserves appendectomy for non-responders and those with recurrent appendicitis.

Several randomised controlled trials (RCT) looked at the NOT of AUA in the adult population. Results, however, vary. Most trials conclude that NOT is safe, but the reported reduction in complications varies from no significant differences7 8 to 86% reduction.9 Recurrent symptoms resulting in delayed appendectomy occur in roughly one in four patients.7 8 10 These numbers are interpreted in different ways, as illustrated by the conclusions of three recent systematic reviews, which range from indicating NOT as the preferred treatment10 to rejecting it as a routine treatment due to insufficient knowledge about its impact on quality of life (QoL).8

Approximately one-third of all cases of appendicitis occur under the age of 20 years. Regarding the distribution of uncomplicated and complicated appendicitis in the paediatric population, the percentage of uncomplicated appendicitis is reported to range from 68% to 90% in children aged 5–18 years.2 11 The percentage of complicated appendicitis increases with age,12 thus reducing the amount of patients suitable for initial NOT strategy. Potential benefits of initial NOT strategy might therefore be higher for the paediatric population than for the adult population. Data in the paediatric population on the outcome of NOT for uncomplicated appendicitis are scarce and consist mainly of uncontrolled studies with small patient numbers. Recently, a systematic review was published, including 10 studies (1 pilot RCT, 6 prospective cohorts and 3 retrospective cohorts) with a total of 413 children treated with NOT.13 Overall complications where reported in five of the six comparative studies. One out of 175 (0.6%) patients in the NOT group suffered complications versus 9/239 (3.8%) patients in the primary appendectomy group. Follow-up ranged from 8 weeks to 4 years, with 82% of the NOT patients not having undergone appendectomy at follow-up completion. Recurrent appendicitis occurred in 68/396 (17%) patients; this included 19 children who were treated with a second course of antibiotics.

The evidence regarding the outcome of NOT in the paediatric population is far from sufficient. As of today, apart from the trial described in this article, four large clinical studies (three RCTs14–16 and one prospective patient preference study17) are recruiting children for a comparison of primary appendectomy with NOT. In the APAC (Antibiotics versus Primary Appendectomy in Children) trial, we aim to evaluate the effectiveness of the initial NOT strategy (reserving appendectomy for those not responding or with recurrent disease) compared with immediate appendectomy in terms of complications, health-related QoL and costs in children aged 7–17 years with AUA.

Methods and analysis

Study design

The APAC trial is a multicentre, non-inferiority RCT. Blinding was not deemed feasible. The protocol was drafted in accordance with the SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) statements.18 This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02848820) and the Dutch Trial Registry (NTR5977) prior to the start of inclusion.

Patient selection

Eligible for inclusion are children 7–17 years old of both sexes, in whom an imaging-confirmed AUA is diagnosed in the emergency department of one of the participating hospitals.

Inclusion criteria

Definition of AUA is based on the following criteria:

- Clinical and biochemical criteria:

- Localised tenderness in the right iliac fossa region

- Normal/hyperactive bowel sounds

- No guarding or palpable mass

- Biochemical signs of infection

- Elevated white blood cell count

- Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Ultrasound criteria to confirm the diagnosis of AUA:

- A non-compressible, painful appendix with an outer diameter >6 mm

- Secondary signs of inflammation, that is, infiltration of the surrounding fat

- Hyperaemia within the appendiceal wall

In case the ultrasound is inconclusive, additional imaging (MRI or CAT scan) may be obtained.

Exclusion criteria

Generalised peritonitis or sepsis (as defined by the international paediatric sepsis consensus conference19)

- Findings on imaging indicative of complex appendicitis:

- Significant and/or unclear free fluid

- Signs of perforation

- Signs of intra-abdominal abscess or phlegmon

Children with a suspicion of an appendiceal faecalith on imaging studies are excluded, because of its association with a higher risk of NOT failure.20–23

Ultrasound characteristics for an appendicolith are defined as an echogenic, well-defined focus within the appendix with posterior acoustic shadowing.

Serious comorbidity such as cardiac or pulmonary disease with significant haemodynamic consequences, immunodeficiency, malignancy or sickle cell disease

A history of non-operatively treated appendicitis

Suspicion of an underlying malignancy or inflammatory bowel disease

Documented type 1 allergy to the antibiotics used

A complex appendicitis risk score indicative of complex appendicitis

Complex appendicitis risk score

A paediatric scoring system is used24 predicting the risk of having complex appendicitis based on five preoperative variables: abdominal guarding, signs of complex appendicitis on ultrasound, CRP level, temperature and days of abdominal pain. In an independent validation in a second paediatric cohort, a score below 4 had a negative predictive value of 98% (95% CI 88% to 100%). Children presenting with a score of 4 or higher will be excluded from this study because of the risk of having complicated appendicitis.

Randomisation

After written informed consent from parents and child (assent from children under the age of 12), patients are randomised using the web-based randomisation program Castor Electronic Data Capture V.4.10,25 stratified by centre. A variable block algorithm is used to ensure concealment of allocation.

Sample size calculation

A non-inferiority design is used based on the notion that NOT potentially has secondary advantages, for instance, cost reduction and less pain.26 We hypothesise that this might also be the case for QoL. It would thus be sufficient to demonstrate that the outcome in terms of complications is not worse in the NOT group compared with the immediate appendectomy group.

In our pilot study,27 we followed the children eligible for NOT who refused participation in that study and received immediate appendectomy instead of antibiotic treatment. The frequency of postoperative complications in this group at 1-year follow-up was approximately 10% (unpublished data), meaning that 90% was successfully treated without complications in the operative group. If the difference in complication rate between NOT and operative treatment is less than 5% in favour of appendectomy, non-inferiority is assumed. We will not be testing for the superiority of NOT. Using a one-sided alpha of 2.5% in accordance with the non-inferiority design, 150 patients per group are needed to achieve 90% power for the exclusion of a difference in favour of the usual care group of more than 5%. Although in our pilot study27 the dropout rate after 1 year was only 2%, we take into account a dropout rate of 10%. Therefore, the number of patients to be included is 334.

Study setting and feasibility

Eligible patients are recruited in 15 hospitals across the Netherlands. This selection consists of both academic and large teaching hospitals. Inclusion started in January 2017. Based on data supplied by the participating hospitals, approximately 225 children per year will meet the inclusion criteria. In our pilot study, 57% of eligible patients participated. Taking these numbers into account, we expect to include 128 patients per year. We therefore expect to complete inclusion within 32 months. All of the clinical, biochemical and imaging assessments are part of the standard work-up for children suspected of having appendicitis in the Netherlands, as described in the Dutch national guideline.28

Interventions

Non-operative management

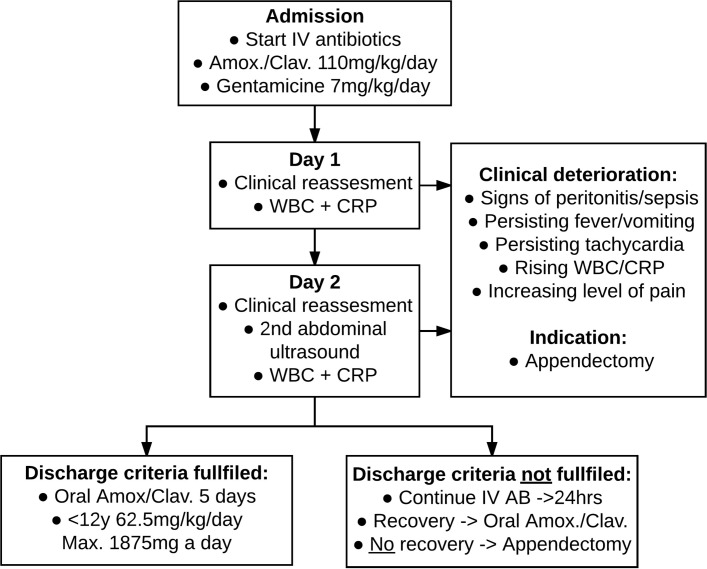

Antibiotic treatment consists of 48 hours of intravenous amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 25/2.5 mg/kg every 6 hours (maximum dose: 6000/600 mg/day) and gentamicin (7 mg/kg once daily). When the patient meets the predefined discharge criteria after 48 hours (box 1), he/she is discharged with oral antibiotics. If not, intravenous antibiotics are continued with a maximum total duration of 72 hours. Oral treatment consists of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 50/12.5 mg/kg in three daily doses (maximum dose: 1500/375 mg/day). Total duration of antibiotic treatment is 7 days.

Box. 1. Predefined discharge criteria. All criteria have to be met to allow patients to be discharged.

Predefined discharge criteria (equal for both interventions):

Body temperature <38.0°C

NRS<4

Adequate oral intake

Able to mobilise

Consent of parents for discharge

Predefined discharge only for non-operative management:

Decreased leucocytosis

Decreased C-reactive protein

No signs of complex appendicitis on second ultrasound

To optimise early detection of NOT failure, white blood cell and CRP are measured every 24 hours during the time of administration of intravenous antibiotics. After 48 hours, the abdominal ultrasound is repeated to check for signs of complicated appendicitis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of non-operative management. CRP, C-reactive protein; WBC, white blood cell.

A physician reassesses the patient twice daily. Vital parameters, including numeric rating scale (NRS) pain scores, are repeated every 6 hours. Intravenous fluid administration is protocolised and weight adjusted, with no oral intake during the first 12 hours. Pain medication is prescribed according to the national guideline.29

Predefined criteria are in place to define the indication for appendectomy (figure 1). In detail: a white blood cell count of more than 20×109/L, increasing white blood cell count/CRP levels after 48 hours are criteria for clinical deterioration. An increasing pain level is defined as a higher NRS score than on admission despite of adequate pain medication according to protocol.

If the patient meets any of these criteria, the decision can be made to proceed with urgent appendectomy or to perform additional imaging studies. This decision is at the discretion of the surgeon in charge of the patient’s care and does not lie with study coordinators. However, it is common practice for the treating surgeon to consult with the study coordinators on the appropriate course of action.

Operative management

Intravenous fluids and pain medication are administered according to the same protocol as the NOT group. Antibiotic prophylaxis, operative approach and postoperative care are all according to local protocol. Postoperative antibiotics are only warranted in the event of an unexpected complex appendicitis. Discharge is allowed when the predefined discharge criteria have been met (box1).

Outcome and statistical analysis

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is defined as the complication rate at 1-year follow-up. An independent adjudication committee will review all complications and adverse events to assess their relation to the allocated treatment. The adjudication committee will categorise all complications using the Clavien-Dindo system.30 The Clavien-Dindo system was developed for reporting surgical complications. However, we expect that all possible complications of NOT can also be categorised within the same system, making a comparison between the two groups more consistent. We will report both the overall complication rate as well as subgroups based on complication severity. Any form of delayed appendectomy is not considered a complication, as we consider appendectomy necessary in patients who do not respond to initial non-operative management. This includes early failure during initial admission and recurrent appendicitis after initial discharge. Complications as a result of a delayed appendectomy are included in the primary outcome.

Complications are defined as, but not limited to:

Complications of antibiotic use: allergic reaction with the need for treatment, gastrointestinal symptoms with the need for treatment, secondary infections, and so on

Need for surgical or radiological intervention other than appendectomy but related to appendicitis

Readmission for an indication other than recurrent appendicitis but related to the allocated treatment

- Complications associated with appendectomy:

- Surgical site infection: incisional and organ space as defined by the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) criteria.31 We do not differentiate between superficial and deep-incisional infection

- Stump leakage/stump appendicitis in need of antibiotic treatment or surgical/radiological intervention

- Secondary bowel obstruction confirmed by imaging or per-operative diagnosis with the need for (non-surgical) treatment. For instance, as a result of adhesions

- Anaesthesia-related complications, such as pneumonia (in need of antibiotic treatment)

- Incisional hernia. Defined as any abdominal wall gap with or without a bulge in the area of a postoperative scar perceptible or palpable by clinical examination or imaging

Secondary outcomes

The rate of delayed appendectomy is reported as a secondary outcome. To evaluate the secondary endpoints, follow-up will take place at 7 days, 4 weeks, 6 months and 1 year after randomisation. Other secondary outcomes are listed below:

- Appendectomy-related endpoints:

- Percentage of patients not having to undergo appendectomy

- Percentage of patients with a missed diagnosis of complex appendicitis

- Percentage of patients having to undergo appendectomy during initial antibiotic course

- Patients with recurrent appendicitis within 1 year (histopathologically confirmed)

- Percentage of patients undergoing interval appendectomy (histopathologically no sign of recurrent appendicitis)

- Patient-related endpoints:

- Level of pain: assessed by the NRS and total usage of pain medication on day 7

- Patient satisfaction assessed with the Net Promoter Score and the validated Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18)34

- Number of days absent from school, social or sport events (patient level)

- Number of days absent from work (parent level)

- Total number of extra visits to the outpatient clinic, general practitioner’s office or emergency department for abdominal pain

- Total length of hospital stay during the follow-up period, including admissions due to complications related to the allocated treatment. The length of initial hospital stay is included but will also be reported separately

- Cost-related endpoints:

- Actual healthcare costs: variables gathered are, but not limited to, number of follow-up outpatient clinic visits, number of general practitioner visits, number of emergency department visits and actual in-hospital generated costs

Data analysis plan

The primary analysis will be done according to the intention-to-treat principle. A per-protocol analysis will be performed as well to prevent unjust rejection of the null hypothesis, which is a risk in non-inferiority research.37 We only consider cases as a treatment arm crossover if the randomly assigned treatment is switched because of patient and/or parental preference without their being medical grounds. Therefore, patients receiving an appendectomy because of clinical deterioration, abdominal complaints after discharge, or recurrent appendicitis will not be labelled as a crossover. We will use multiple logistic and linear regression analyses for binary and continuous outcomes, respectively, to adjust for stratification factors. Differences in proportions, numbers needed to treat, and absolute and relative differences in continuous outcomes will be presented with the corresponding 95% CI, except for the percentage of patients with complications within 1 year (primary outcome), for which a one-sided 97.5% CI limit will be given in accordance with the non-inferiority design. In a secondary analysis, the information recorded during the initial hospital stay will be analysed using multiple logistic regression analysis in order to identify potential predictive variables for NOT failure. Statistical analyses will be performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.22.0 or higher (IBM, released 2013).

Ethics and dissemination

Data collection and confidentiality

All data are handled confidentially and access is strictly limited in accordance with the Dutch Personal Data Protection Act. All participants are assigned a unique study code, which is not based on the patient initials or birth date. The master sheet only contains the study code and patient identification information. Data are gathered through clinical observations, outpatient clinic visits, follow-up phone calls and online questionnaires. All data are collected via Castor Electronic Data Capture,25 a web-based electronic case record form, which is built, maintained and has an audit trail all according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All data will be stored for a period of at least 15 years.

Monitoring and safety

Reliable high-quality data are deemed of the upmost importance. The Clinical Research Bureau of the VU University Medical Centre will provide external monitoring, with monitoring visits of each participating centre at least once a year.

The accredited Medical Ethics Review Committee of the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam (MERC AMC) will be informed annually. All (serious) adverse events, suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSAR) and any other significant problems are reported to the MERC using an online submission system. To further assure the safety of participants, an independent Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) is installed, consisting of a surgeon, a paediatrician and a statistician. They receive an overview of the primary outcome every 6 months, as well as serious adverse events, SUSARs and the number of patients having to undergo a delayed appendectomy. An interim analysis for efficacy will not be performed. If a serious concern arises for the safety of the patients in the trial, the DSMB can recommend early termination of the study. These agreements have been documented in a DSMB charter.

Ethics

The trial will be conducted in compliance with the current version of the Declaration of Helsinki, the ICH Good Clinical Practice guidelines E6(R1) and in accordance with the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO).

Withdrawal

Subjects can withdraw from the study without explanation at any time. They will be asked their reason for withdrawal, and they will be asked for permission to use their data. In case of withdrawal, the patient will be treated according to the national protocol, which would be an appendectomy. However, the surgeon in charge of care can decide otherwise in agreement with the patient and his or her family. Patients can also be withdrawn by the surgeon or the investigator for urgent medical reasons.

Dissemination plan

Dispersion of the trial results will be accomplished by publication in an international peer-reviewed scientific journal and by presentations at (international) conferences. When the results of the trial warrant changes in the standard treatment guidelines of simple appendicitis, we reckon that the widespread execution of the trial in centres throughout the Netherlands will aid in its implementation.

Implementation study

To ensure optimal implementation a problem analysis will be conducted parallel to this RCT, investigating the promoting and obstructing determinants of implementation from patient, surgeon, organisational and social-political perspective. This qualitative study will include structured interviews with patients, parents, professionals and other stakeholders.

Discussion

Strengths and limitations of this study

This trial only includes patients with imaging-confirmed appendicitis, thus reducing the risk of including patients with other diagnoses, or those with a non-inflamed appendix. Since the implementation of a guideline in the Netherlands promoting preoperative imaging, the per-operative finding of non-inflamed appendices was reduced to 3.3%,38 which is low compared with, for example, the UK, where it is 20.6%.39 We postulate that our use of elaborate and, where possible, evidence-based patient selection methods enhances the chance of successful non-operative management. To warrant the safety of patients undergoing NOT, this protocol dictates systematic and frequent evaluation (by clinical assessment, laboratory tests and imaging studies). We expect this will identify patients not responding to the antibiotic treatment at an early stage.

The non-inferiority design does not allow for a superiority comparison for the rate of complications. The design choice was based on the argument that both treatment strategies are 100% effective in treating appendicitis, because when antibiotic treatment is not successful and when recurrent appendicitis occurs, appendectomy is performed. We postulate that the non-operatively treated patients who do not require appendectomy will have a reduction in costs, better QoL and the avoidance of the complications associated with appendectomy. Essential for the possible acceptance of this new strategy is that it is not inferior when it comes to the risk of complications. To determine the severity of possible complications and their relation with the allocated treatment, we consider the support of an independent adjudication committee a great asset.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria of this trial are mostly based on data that allow for distinguishing complex from uncomplicated appendicitis. Criteria that predict the risk of NOT failure would be more adequate. However, more data and more experience are needed to be able to develop such criteria. Data from the APAC trial will also be used to analyse predictors of failure.

Choice of primary outcome

Determining the appropriate primary outcome measure in studies comparing NOT with operative treatment remains challenging. In our opinion, both strategies will be effective in treating patients with appendicitis, and therefore effectiveness or failure is not an appropriate outcome measure. Therefore, we decided to use a composite outcome measure, that is, complications. Such outcome measures (morbidity and mortality) are necessary in order to start the debate whether or not NOT strategy can be integrated in clinical practice.

Furthermore, our goal is to compare the initial NOT strategy (reserving an appendectomy for those not responding or with recurrent appendicitis) with direct operative treatment strategy. In this view, stating that delayed appendectomy for the indication of failed antibiotic treatment or recurrent appendicitis is a complication would not be appropriate as it is integrated in the treatment strategy. Postoperative complications after delayed appendectomy are however considered as complications of the initial NOT strategy. The amount of delayed appendectomies (for both non-responders and recurrent appendicitis) needs to be included in the debate whether or not initial NOT strategy can be implemented in daily practice. It is therefore reported as a secondary outcome.

Complicated appendicitis

Reluctance of some surgeons towards NOT might be explained by the fear of missing complicated appendicitis and delaying appropriate treatment. In 4.5%–6.5% of the adult population treated with NOT who underwent delayed appendectomy, complicated appendicitis was found.7 10 The outcome in terms of postappendectomy complications after delayed appendectomy (6.9%) is comparable to that for primary appendectomy (8.8%).8

Exclusion of patients with appendiceal faecalith

We excluded patients with a suspicion of an appendiceal faecalith on preoperative imaging studies because it is associated with a higher failure rate of NOT. In the adult population, a NOT failure rate of 50% after 1 month was reported in the group with a faecalith versus 14% in the group without a faecalith.20 One study only including children with appendicitis and a faecalith on imaging had to terminate inclusions early because of a NOT failure rate of 60% at a median of 4.7 months’ follow-up.23 Faecaliths are also associated with a higher long-term recurrence risk in children, with recurrences of 47.4% vs 23.7%.21

Follow-up/long-term effects

Information regarding long-term results of NOT in simple appendicitis is limited and it is scarce in children. One study in children with an average follow-up of 4.3 years reported that 22 of 78 (29%) children treated with NOT experienced recurrent appendicitis,21 with a median time to recurrence of 6 months. Eight per cent of all non-operatively treated children experienced recurrence after more than 1 year. The APAC trial has a follow-up of 1 year. However, all participants who have not been operated at the end of the study will be asked to participate in long-term follow-up. The long-term effects in children of losing the function of the appendix have also not yet been cleared up. The appendix might play a role in immunity and there is evidence that it is involved in preserving a healthy gut microbiome.40

Choice of antibiotic regime

Most of the data on antibiotic susceptibility in appendicitis is derived from studies in adults, patients with complicated appendicitis and mixed patient groups. There is some evidence available concerning children. A study analysing cultures from children in Ireland with complicated appendicitis revealed that the combination therapy of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and aminoglycosides would be appropriate in 99% of children with bacterial appendicitis-related peritonitis.41 Since antibiotic resistance rates are greatly dependent on geography, we can expect comparable or even better results in the Netherlands, considering it has the lowest rates of antibiotic use in Europe.42 Combined with a low rate of complications and extensive experience with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and gentamicin, we consider it the most sensible regime. Further research is carried out by our research group analysing the microbiome in simple and complicated appendicitis. Hopefully, this will contribute in determining the best antibiotic regime. If NOT of appendicitis is shown to be non-inferior in this trial, further research should determine the most sensible regime and treatment duration. The first pilot RCT evaluating outpatient conservative management in a mixed group (children and adults) has already been published.43

Antibiotic resistance

A possible downside of NOT as opposed to surgery could be increased antibiotic resistance.44 Interestingly, a study evaluating bacterial resistance in complicated appendicitis in children showed no significant increase in resistance rates over the past 20 years.45 How this translates to bacterial resistance when simple appendicitis is treated with antibiotics is unclear. The use of multidrug treatment regimens has been pointed out as one of the possibilities to reduce the development of resistant bacteria.46 Our choice for amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and gentamicin prevents us from having to use so-called reserve antibiotics, unlike most of the other known studies in children, in which for instance piperacillin-tazobactam is the drug of choice. Also when the symptoms do not resolve under the chosen antibiotic regimen, appendectomy is performed; we do not switch to other antibiotics.

Value of histological evaluation

An occasionally mentioned argument8 against NOT of appendicitis is the risk of missing other underlying causes of appendicitis, such as a carcinoid. One study repeated the abdominal ultrasound in children 1–3 months after NOT to ensure the diameter of the appendix returned to normal.21 The value of this strategy is unknown. In an analysis of 241 histopathological appendectomy samples in children with simple appendicitis, 4 (1.6%) showed unexpected findings.47 Three parasitic infections and one Walthard cell rest were found; none of the findings required further treatment or investigation. The frequency of appendiceal carcinoid tumours in children undergoing appendectomy was 0.2%,48 and in less than 20% of these cases lymphovascular or mesenteric involvement was present. This seems a negligible risk and it is yet unclear if patients who are excluded or unresponsive to NOT are also the patients with the highest risk of having a malignancy as underlying cause.

Unique for the APAC trial is its primary outcome measure; total number of complications after 1 year. Delayed appendectomy or recurrence is not reported as the primary endpoint or as a complication. Because in our opinion there is a place for the appendectomy in non-operative management as a step-up approach for children unresponsive to antibiotic treatment. As a result, 8 or 9 out of every 10 children with uncomplicated appendicitis would no longer have to undergo an appendectomy. Furthermore, if we are able to identify specific predictive preoperative variables, we might identify a group of patients with even better (long-term) outcomes. Finally, this trial should answer the question whether the advantages of NOT are also reflected in the reported QoL and diminished costs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Due to the multicentre and multidisciplinary nature of the trial, not all supporting researchers can be mentioned by name. However, we acknowledge all supporting paediatricians, radiologists, pharmacists, emergency medicine physicians and paediatric nurses. We also thank all the supporting staff and other physicians who made the realisation of this trial possible. We acknowledge the Dutch Foundation Children and Hospital for their advice and support in drafting the protocol.

Footnotes

Contributor: The APAC collaborative study group includes the following contributors: H. Rippen, P.M. Bet, G. Kazemier, C.M.F. Kneepkens, R. Wijnen, M. Offringa, N. Ahmadi, H.J. Bonjer, R.R. van Rijn, M.A. Benninga, W.A. Bemelman, D.L. Hilarius, S.A.J.M van Veen, P.M.N.Y.H. Go, H.A. Cense, A. de Vries, J. Straatman, K.H. in ’t Hof, E.J.A.H. van Beek, M.H.M. Bender, L.C.L. van den Hill, H.W. Bolhuis, K. Treskes, T.S. Bijlsma, N. Geubbels, I de Blaauw, S. M.B.I. Botden, V.J. Leijdekkers, M. C. Boonstra, L.H. Rongen, E.J.G. Boerma, M.D.P. Luyer, G. Vugts, T. Copper, F.P. Garssen, C. Hulsker, R.G.J. Visschers

Contributors: All authors have contributed to the design of this trial protocol. RRG, JHvdL and HAH have initiated the project. LWEvH and RB are the chief investigators. The protocol was drafted by RRG which was refined by JHvdL, SMLT, LWEvH, RB and HAH. Statistical advice was provided by JHvdL. MK was responsible for drafting the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. The APAC collaborative study group consists of all local investigators who are responsible for the execution of the trial and valid data gathering. They have all read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) (grant number 843002708).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol has been approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee of the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: The surgical, pediatric, radiology, pharmacy and emergency medicine departments of the following Dutch hospitals contribute to the execution of this trial: Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Ziekenhuis Amstelland, Amstelveen, The Netherlands; Catharina Ziekenhuis, Eindhoven, The Netherlands; Elkerliek Ziekenhuis, Helmond, The Netherlands; Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Flevoziekenhuis, Almere, The Netherlands; Gelre Ziekenhuis, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands; Maxima Medical Center, Veldhoven, The Netherlands; Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, The Netherlands; Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep, Alkmaar, The Netherlands; OLVG, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Rode Kruis Ziekenhuis, Beverwijk, The Netherlands; St. Antonius Ziekenhuis, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands; University Medical Center Radboud, Nijmegen, The Netherlands; University Medical Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands; VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Zuyderland, Heerlen/Sittard, The Netherlands.

References

- 1.Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, et al. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 1990;132:910–25. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson JE, Bickler SW, Chang DC, et al. Examining a common disease with unknown etiology: trends in epidemiology and surgical management of appendicitis in California, 1995-2009. World J Surg 2012;36:2787–94. 10.1007/s00268-012-1749-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Livingston EH, Woodward WA, Sarosi GA, et al. Disconnect between incidence of nonperforated and perforated appendicitis: implications for pathophysiology and management. Ann Surg 2007;245:886–92. 10.1097/01.sla.0000256391.05233.aa [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson RE. The natural history and traditional management of appendicitis revisited: spontaneous resolution and predominance of prehospital perforations imply that a correct diagnosis is more important than an early diagnosis. World J Surg 2007;31:86–92. 10.1007/s00268-006-0056-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubér M, Andersson M, Petersson BF, et al. Systemic Th17-like cytokine pattern in gangrenous appendicitis but not in phlegmonous appendicitis. Surgery 2010;147:366–72. 10.1016/j.surg.2009.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carr NJ. The pathology of acute appendicitis. Ann Diagn Pathol 2000;4:46–58. 10.1016/S1092-9134(00)90011-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sallinen V, Akl EA, You JJ, et al. Meta-analysis of antibiotics versus appendicectomy for non-perforated acute appendicitis. Br J Surg 2016;103:656–67. 10.1002/bjs.10147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harnoss JC, Zelienka I, Probst P, et al. Antibiotics versus surgical therapy for uncomplicated appendicitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials (prospero 2015: Crd42015016882). Ann Surg 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salminen P, Paajanen H, Rautio T, et al. Antibiotic therapy vs appendectomy for treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis. JAMA 2015;313:2340 10.1001/jama.2015.6154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rollins KE, Varadhan KK, Neal KR, et al. Antibiotics versus appendicectomy for the treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis: An updated meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. World J Surg 2016;40:2305–18. 10.1007/s00268-016-3561-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wesson DE. Acute appendicitis in children: clinical manifestations and diagnosis - Up to date [Internet]. 2017. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acute-appendicitis-in-children-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis (cited 7 Jun 2017).

- 12.Al-Omran M, Mamdani M, McLeod RS. Epidemiologic features of acute appendicitis in Ontario, Canada. Can J Surg 2003;46:263–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Georgiou R, Eaton S, Stanton MP, et al. Efficacy and safety of non-operative treatment for acute appendicitis: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20163003 10.1542/peds.2016-3003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu J, Liu YC, Adams S, et al. Acute uncomplicated appendicitis study: rationale and protocol for a multicentre, prospective randomised controlled non-inferiority study to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of non-operative management in children with acute uncomplicated appendicitis. BMJ Open 2016;6:e013299 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall NJ, Eaton S, Abbo O, et al. Appendectomy versus non-operative treatment for acute uncomplicated appendicitis in children: study protocol for a multicentre, open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. BMJ Paediatrics Open 2017;1:bmjpo-2017-000028 10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher J. Comparison of medical and surgical treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis in children - clinical trials.gov [Internet]. 2016. Last updated: December 9, 2016 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02991937 (accessed 7 Jun 2017).

- 17.Peter Minneci NCH. Multi-institutional trial of non-operative management of appendicitis - clinicaltrials.gov [Internet]. 2014. Last updated: 18 Aug 2016 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02271932 (accessed 7 Jun 2017).

- 18.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2005;6:2–8. 10.1097/01.PCC.0000149131.72248.E6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vons C, Barry C, Maitre S, et al. Amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid versus appendicectomy for treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:1573–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60410-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka Y, Uchida H, Kawashima H, et al. Long-term outcomes of operative versus nonoperative treatment for uncomplicated appendicitis. J Pediatr Surg 2015;50:1893–7. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Svensson JF, Patkova B, Almström M, et al. Non-operative treatment with antibiotics versus surgery for acute nonperforated appendicitis in children. Ann Surg 2015;261:67–71. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahida JB, Lodwick DL, Nacion KM, et al. High failure rate of nonoperative management of acute appendicitis with an appendicolith in children. J Pediatr Surg 2016;51:908–11. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.02.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorter RR, van den Boom AL, Heij HA, et al. A scoring system to predict the severity of appendicitis in children. J Surg Res 2016;200:452–9. 10.1016/j.jss.2015.08.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castor Electronic Data Capture. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Ciwit BV, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu J, Adams S, Liu YC, et al. Nonoperative management in children with early acute appendicitis: A systematic review. J Pediatr Surg 2017;52:1409–15. Epub ahead of print 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorter RR, van der Lee JH, Cense HA, et al. Initial antibiotic treatment for acute simple appendicitis in children is safe: Short-term results from a multicenter, prospective cohort study. Surgery 2015;157:916–23. 10.1016/j.surg.2015.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dutch Association for Surgery. Dutch national guideline: diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dutch Association of Pediatrics. Dutch national guideline: pain measurement and management of pain in children. Utrecht, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 2009;250:187–96. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control 2008;36:309–32. 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landgraf JM, Abetz LWJ. The CHQ User’s Manual. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wille N, Badia X, Bonsel G, et al. Development of the EQ-5D-Y: a child-friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res 2010;19:875–86. 10.1007/s11136-010-9648-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thayaparan AJ, Mahdi E. The patient satisfaction questionnaire short form (psq-18) as an adaptable, reliable, and validated tool for use in various settings. Med Educ Online 2013;1821747 10.3402/meo.v18i0.21747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bouwmans C, Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Koopmanschap M, et al. Manuel: iMTA Medical Cost Questionnaire (iMCQ. Rotterdam: iMTA, Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bouwmans C, Krol M, Severens H, et al. The iMTA Productivity Cost Questionnaire: a Standardized Instrument for Measuring and Valuing Health-Related Productivity Losses. Value Health 2015;18:753–8. 10.1016/j.jval.2015.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rehal S, Morris TP, Fielding K, et al. Non-inferiority trials: are they inferior? A systematic review of reporting in major medical journals. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012594 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Rossem CC, Bolmers MD, Schreinemacher MH, et al. Prospective nationwide outcome audit of surgery for suspected acute appendicitis. Br J Surg 2016;103:144–51. 10.1002/bjs.9964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Surgical Research Collaborative. Multicentre observational study of performance variation in provision and outcome of emergency appendicectomy. Br J Surg 2013;100:1240–52. 10.1002/bjs.9201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Randal Bollinger R, Barbas AS, Bush EL, et al. Biofilms in the large bowel suggest an apparent function of the human vermiform appendix. J Theor Biol 2007;249:826–31. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Obinwa O, Casidy M, Flynn J. The microbiology of bacterial peritonitis due to appendicitis in children. Ir J Med Sci 2014;183:585–91. 10.1007/s11845-013-1055-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Stockholm 2015. ECDC Summary of the latest data on antibiotic consumption in the EU Antibiotic consumption in Europe. 2015.

- 43.Talan DA, Saltzman DJ, Mower WR, et al. Antibiotics-First Versus Surgery for Appendicitis: A US Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial Allowing Outpatient Antibiotic Management. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:1–11. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.08.446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersson RE. The role of antibiotic therapy in the management of acute appendicitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2013;15:10–13. 10.1007/s11908-012-0303-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmitt F, Clermidi P, Dorsi M, et al. Bacterial studies of complicated appendicitis over a 20-year period and their impact on empirical antibiotic treatment. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:2055–62. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hughes D, Andersson DI. Evolutionary consequences of drug resistance: shared principles across diverse targets and organisms. Nat Rev Genet 2015;16:459–71. 10.1038/nrg3922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gorter RR, van Amstel P, van der Lee JH, et al. Unexpected findings after surgery for suspected appendicitis rarely change treatment in pediatric patients; Results from a cohort study. J Pediatr Surg 2017;52:1269–72. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fallon SC, Hicks MJ, Carpenter JL, et al. Management of appendiceal carcinoid tumors in children. J Surg Res 2015;198:384–7. 10.1016/j.jss.2015.03.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.