Abstract

Introduction

Falls are a major global public health problem and leading cause of accidental or unintentional injury and hospitalisation. Falls in hospital are associated with longer length of stay, readmissions and poor outcomes. Falls prevention is informed by knowledge of reversible falls risk factors and accurate risk identification. The extent to which hospital falls are prevented by evidence-based practice, patient self-management initiatives, environmental modifications and optimisation of falls prevention systems awaits confirmation. Published reviews have mainly evaluated community settings and residential care facilities. A better understanding of hospital falls and the most effective strategies to prevent them is vital to keeping people safe.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of falls prevention interventions on reducing falls in hospitalised adults (acute and subacute wards, rehabilitation, mental health, operating theatre and emergency departments). We also summarise components of effective falls prevention interventions.

Methods and analysis

This protocol has been registered. The systematic review will be informed by Cochrane guidelines and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis statement. Inclusion criteria: randomised controlled trials, quasi-randomised trials or controlled clinical trials that evaluate falls prevention interventions for use by hospitalised adults or employees. Electronic databases will be searched using key terms including falls, accidental falls, prevention, hospital, rehabilitation, emergency, mental health, acute and subacute. Pairs of independent reviewers will conduct all review steps. Included studies will be evaluated for risk of bias. Data for variables such as age, participant characteristics, settings and interventions will be extracted and analysed with descriptive statistics and meta-analysis where possible. The results will be presented textually, with flow charts, summary tables, statistical analysis (and meta-analysis where possible) and narrative summaries.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required. The systematic review will be published in a peer-reviewed journal and disseminated electronically, in print and at conferences. Updates will guide healthcare translation into practice.

Trail registration number

PROSPERO 2017: CRD 42017058887. Available from https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero

Keywords: falls prevention, hospitalised adults, evidence-based practice, systematic review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We will systematically identify and critically appraise the available evidence for effectiveness of hospital falls prevention methods.

We have endeavoured to reduce bias by using a priori inclusion/exclusion criteria, data extraction procedures and risk of bias assessments.

The study screening, data extraction and assessment of risk of bias will be conducted independently by two authors and a third will arbitrate on disagreements.

Falls prevention methods targeted towards patients as well as employee-focused education and training systems and processes for patient falls prevention will be evaluated.

The inclusion of only English-language publications, due to a lack of translation resources, means that potential exists for cultural and publication bias.

Background

Description of the condition

WHO has reported that falls are a major global public health problem and a leading worldwide cause of accidental or unintentional injury deaths after road traffic accidents.1 The estimated number of falls deaths is approximately 424 000 globally with falls responsible for 17 million disability-adjusted life years. Adults over 65 years are at greatest risk.2 3 Over one in three adults fall annually, and falls are the main cause of hip fractures4 and hospitalisation.5 The financial costs from fall-related injuries are considerable,6 and the average cost per fall in the group older than 65 years has been estimated as $3611 in Finland and US$1049 in Australia.7–9 Fall-related injuries in the USA (2014) resulted in an estimated US$31 billion in annual Medicare costs,10 and in the UK, falls are estimated to cost the UK health system over £2 billion per year.11 Rates of falling events and injuries from falls increase with advancing age and are particularly high for people with chronic conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease and dementia.12 13

Falls are the most common adverse events that are reported in hospitalised older adults, with geriatric and rehabilitation wards having the greatest incidence.5 6 Falls in hospital are associated with longer length of stay and poorer outcomes for patients.4 5 Between 30% and 40% of falls in hospital result in physical injury such as bruises, hip fractures and head injuries.14–16

In hospital settings, an incidence of 3.4–3.9 falls per person year has been reported in geriatric rehabilitation wards17 18 and 6.2 falls per person year in psychogeriatric wards.7 Evidence syntheses show that risk factors for falls in hospital inpatients include gait instability, delirium, cognitive impairment, urinary incontinence, a history of previous falls, visual impairment, multimorbidity and psychotropic medications.5 For older adults in rehabilitation settings, falls risk factors further include carpet flooring; vestibular dysfunction; delirium; dementia; sleep disturbance; medications such as anticonvulsants, tranquillisers and antihypertensives; and dependence on assistance with transfers.4 8 17 18

The most current Cochrane systematic review was published in 2012 and evaluated the efficacy interventions for preventing falls in older people in both residential care facilities and hospitals. In residential and nursing care facilities, vitamin D supplementation was effective in reducing the rate of falls, yet the efficacy of exercise was unclear.4 In contrast, exercise in subacute hospitals and geriatric rehabilitation centres appears effective.4 Multifactorial interventions that include aerobic exercises, strength training, mobility strategies, medication management, consumer and staff education, provision of effective assistive devices and environmental modifications reduce falls in hospitals (RaR: 0.69, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.96: I²=59%) and risk of falling (risk ratio (RR) 0.71, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.09: I²=43%).4 13 17–20 However, optimal type and dosage of these multifactorial falls prevention interventions remain unclear.21 22 A recent trial that evaluated a combination of four interventions on acute medical and surgical wards showed no effect in reducing falls.23 Further evaluation of individual interventions such as alarms or provision of low-low beds and hourly nursing rounds is required.24–27 A trial that provided individualised patient education with staff feedback significantly reduced falls by 40% and injurious falls in rehabilitation wards.19

Description of the intervention

The majority of falls are the result of a combination of factors, and a wide range of falls prevention methods have been reported. Accurate fall risk assessment is essential. In addition, hospital falls prevention interventions may include patient education, clinician training and environmental modifications. Hospital systems, policies and procedures for preventing falls can also influence outcome by optimising organisational practices.

Why is it important to do this review?

Falls prevention assessments and interventions are informed by knowledge of the reversible risk factors for falls. They are also informed by an ability to identify and manage adult falls risk, as well as by managing the environment and staff practices and behaviours. Published reviews have mainly evaluated community settings and residential care facilities.7 8 There is limited evidence showing which approaches prevent falls in hospitals.

A better understanding of the nature of falls and the most effective strategies to prevent falls in hospital programmes is vital to keep adults safe when they are admitted to hospital. Studies to date have not been able to identify which components of falls prevention (including risk assessment and management tools) should be combined to deliver best practice management in hospitals.

Review question

What are the effects of falls prevention interventions on falls outcomes for adults in hospital settings?

Aims

Evaluate the effectiveness of falls prevention interventions on reducing falls in hospitalised adults (acute and subacute wards, rehabilitation, mental health, operating theatre and emergency departments).

Describe and summarise the components of effective hospital falls prevention interventions.

Methods and design

This protocol has been registered on PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews (registration number: CRD 42017058887 and available at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero), and is reported using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocol (PRISMA-P).28 29 We will conduct a systematic review informed by Cochrane guidelines30 and reported according to the PRISMA statement.31 32 In the event of protocol amendments, the date of each amendment will be accompanied by a description of the change and the rationale and SS and MM will be responsible for approving, documenting and implementing them. An updated protocol will be identified with a new version number and a list of specific amendments that were made to the previous version.

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies

Studies will be included if they are randomised controlled trials, quasi-randomised trials or controlled clinical trials. In the absence of these methods, we will consider comparative studies without randomisation, cohort studies and case-controlled studies. Studies will be excluded if not published in English (due to a lack of translation resources). Publications that are reports, reviews, dissertations, letters, comments, books, expert opinion or practice papers will be excluded.

Types of interventions

The review will consider studies that evaluate falls prevention interventions, including but not limited to education (including one–one/group/written/telephone/e-health, online programmes and apps), exercises, functional assistance as a falls prevention strategy, health professional education, medications either withdrawing or delivered for falls prevention or multifactorial combinations of the preceding strategies. The interventions must have been delivered in hospital settings.

Comparators

The interventions will be compared, but not limited, to control conditions where there are no falls prevention interventions, where usual care is provided or where the intervention group receives falls prevention in addition to usual care or another falls prevention approach.

Outcome measures

We will include trials with data at baseline and data during and/or after the investigated intervention. Trials must report raw data that allow calculations to be made or statistics relating to rate or number of any type of fall or the number of participants sustaining a fall during follow-up. The primary outcomes will be rate of falls (eg, expressed as the number of falls per 1000 person days), number of falls, number of fallers (proportion of participants whom became fallers expressed as a percentage of the participants who fell) and time to first fall (days).

The secondary outcomes include the number of participants sustaining fall-related injuries (eg, rates of injurious falls expressed as, for example, the number of falls with injury per 1000 patient days) and the number of participants who sustain injuries such as, but not limited to, head injuries or fractures as result of a fall expressed as occurrences per 1000 patient days. Where data are available, an additional outcome of the number of patients sustaining a hip fracture will be expressed as hip fracture per 1000 patient days. Secondary outcomes will also include the proportion of participants with injurious falls expressed as percentage of participants who sustained an injury as the result of a fall. Complications or adverse events reported as resulting from delivering the interventions will also be evaluated. A cost–benefit analysis of healthcare provider costs and costs of environmental modifications is an additional secondary measure.

Study setting

We define hospitals as ‘establishments that are primarily engaged in providing emergency care, inpatient care rehabilitative services, outpatient services and hospital-in-the-home for patients’4 as well as mental health and operating theatre. WHO defines hospitals as ‘healthcare institutions that have an organised medical and other professional staff and inpatient facilities and deliver services 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. They offer a range of acute, convalescent and terminal care using diagnostic and curative services’.33

Types of participants

Studies will be included if they include hospitalised adults aged over 21 years or hospital staff. They will be excluded if they are conducted in a hospice, palliative care, paediatric ward, home or residential care facility.

Identification and selection of studies

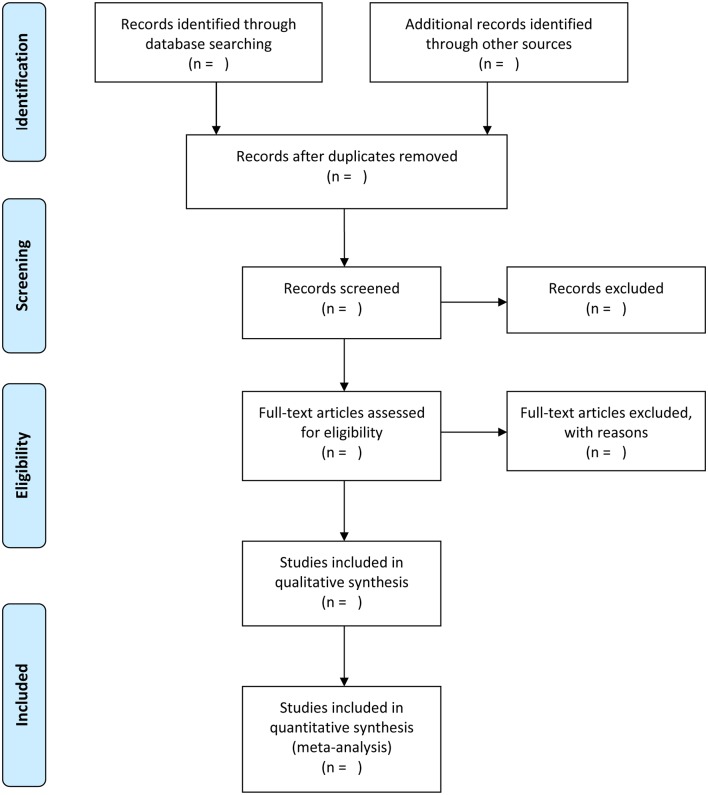

We will search electronic databases including MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, AMED, PEDro, PsychInfo and Sport Discus. A manual search of reference lists and Citation Tracking of relevant studies will also be conducted to identify additional papers, and content experts will be consulted. The search will be conducted without date limits up until March 2017, using explosions and combinations of key search terms including, for example, falls, accidental falls, prevention, hospitals, hospital units, rehabilitation centres, acute care and subacute care. Study selection will be documented and summarised in a PRISMA compliant flow chart (figure 1). A draft MEDLINE search strategy is included in online supplementary appendix 1. The MEDLINE strategy will be adapted to the syntax and subject headings of the other databases.

Figure 1.

Flow chart compliant to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis.

bmjopen-2017-017864supp001.pdf (303KB, pdf)

The search results will be downloaded to a reference database. After deletion of duplicates, one reviewer will perform initial screening of titles by applying the a priori eligibility criteria (online supplementary appendix 2). Two independent researchers from the research team will then screen titles and abstracts of remaining references and perform full-text review as necessary to identify those studies that fulfil selection criteria. Disagreements will be resolved through discussion and a third reviewer from the research team, if consensus cannot initially be reached.

Method quality/risk of bias assessment

Studies considered eligible for inclusion will be evaluated for method quality/risk of bias but not excluded on the basis of method quality. We will use either the PEDro scale34 35 or the Cochrane Risk of Bias Instrument that assesses against 12 criteria: randomisation, concealed allocation, blinding, incomplete data, baseline comparability, intention-to-treat analysis, cointerventions and outcome assessment timing and score each of the individual criteria as ‘high risk’, ‘low risk’ or ‘unclear risk’.30 Reviewers will not be involved in risk of bias assessment for studies on which they were coauthors.

Meta-bias (such as publication bias across studies, selective reporting within studies)

To examine for the presence of reporting bias, we will determine whether the study protocol was published before recruitment of patients of the study was started. For studies published after 1 July 2005, the Clinical Trial Register at the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform of the World Health Organisation (http://apps.who.int/trialssearch) shall be screened for study registration. We will evaluate whether selective reporting of outcomes is present (outcome reporting bias) and compare the fixed-effect estimate against the random-effects model to assess the possible presence of small sample bias in the published literature (whereby the intervention effect is arguably more beneficial in smaller studies). In the presence of small sample bias, the random-effects estimate of the intervention is more beneficial than the fixed-effect estimate.30

Data extraction and management

Pairs of independent reviewers will independently extract data using a pretested standardised data extraction form. The main headings will include: methods, population characteristics, intervention characteristics and both baseline and postintervention outcome scores. We will collect the following information:

Study characteristics (eg, country where the study was conducted, population source (consumer, staff, clinician) or setting, recruitment modality, source of funding, inclusion criteria)

Population characteristics (eg, number of participants, age, sex, type of cohort, whether acute, subacute, mental health, operating theatre, emergency department or rehabilitation setting, average length of stay in hospital; diagnostic criteria will be specified where studies are conducted in a specific population, for example, stroke, amputee, postsurgical cohort)

Intervention characteristics (eg, description of components, falls risk assessment tool, duration and number of sessions, description of how the intervention is delivered, profession delivering the intervention, cointerventions)

For studies that include exercises, the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template will be applied to extract elements of the exercise programme36 37

Outcome data (eg, rate of falls, number of fallers, time to first fall, injuries reported from falls and fear of falling; to calculate rates of falls and injurious falls the observation period, both control and intervention phases will be collected (days)).

Outcome data will be extracted for short-term, medium-term and long-term follow-up assessments, and the corresponding authors of included studies will be contacted to obtain any missing data when needed. The completed data extraction forms will be examined for consistency, and any disagreements will be resolved by discussion and consensus or third party adjudication where necessary.

Data synthesis

We will express dichotomous outcomes as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs and continuous outcomes as mean differences with 95% CIs if different trials used the same measurement instrument to measure the same outcome. We will analyse continuous outcomes using the standardised mean difference when trials measure the same outcome but employ different measurement instruments to measure the same conceptual outcome. For categorical data, we will estimate the proportion of fallers and pooled rate ratios or RRs using a random-effects model. The overall quality of evidence will be summarised with the GRADE approach.30 Meta-analyses will be conducted for each outcome where relevant data from two or more studies are available. We will group interventions by combination (such as single, multiple or multifactorial) and by intervention type (descriptors such as exercise, medication, environmental, assistive, staff education, patient education).

Missing data

When there are missing data, we will attempt to contact the original authors of the study to obtain the relevant missing data. Important numerical data will be carefully evaluated. If missing data cannot be obtained, an imputation method will be used.30 For studies having insufficient data to enter in the meta-analysis, even after contacting the authors, we will report the results qualitatively.30 Sensitivity analysis will be used to assess the impact on the overall treatment effects of inclusion of trials that do not report an intention-to-treat analysis, have high rates of participant attrition or with other missing data. Where data are imputed or calculated (eg, SDs calculated from SEs, 95% CIs or p values or imputed from graphs or from SDs in other trials), we will report this in the tables of characteristics of included studies.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Clinical heterogeneity will be evaluated by considering the variability in participant factors among trials (eg, age) and trial factors (randomisation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, losses to follow-up, treatment type, cointerventions). Heterogeneity will be evaluated using the standard χ2 test to determine whether a fixed-effects or random-effects model is chosen. Quantitative data will, where possible, be pooled for meta-analysis. Where pooling is not possible, the findings will be presented in a narrative form. Subgroup analysis will be explored based on grouping trials that have comparable interventions. We will try to explain the source of heterogeneity by subgroup analysis or sensitivity analysis.30

Meta-analysis

Pooling of data will only occur for studies that investigated the same falls prevention intervention. This means that pooling of data will be done separately for each falls prevention intervention (eg, exercises). Studies having a multimodal approach will be pooled together (eg, exercises, education, environmental adaptations). Meta-analysis will be performed only from studies regarded as suitably homogeneous.30 Homogeneity of studies will be evaluated by exploring their similarities and differences, taking into consideration the study population, type of intervention, reference treatments, outcomes, measurements instruments and timing of follow-up. If a meta-analysis is not possible, the results from clinically comparable trials will be presented descriptively.30

Regardless of whether there are sufficient data available to use quantitative analyses to summarise the data, the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome will be determined. To accomplish this, the GRADE approach and the GRADE guidelines on how to apply the GRADE methodology framework in more detail will be used. Factors that may decrease the quality of the evidence are: study design and risk of bias, inconsistency of results, indirectness (not generalisable), imprecision (sparse data) and other factors (eg, reporting bias). The quality of the evidence for a specific outcome will be reduced by a level, according to the performance of the studies against these five factors.28

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses will be used to explore possible sources of heterogeneity, based on the following:

Patient characteristics (age, diagnosis, type of ward, that is, whether acute, subacute, rehabilitation, operating theatre, mental health, surgical or medical, level of cognition).

Types of treatment: whether single or multifactorial interventions such as those including staff, inpatients and/or carers or environmental modifications.

Types of transport modes or assistive devices such as wheelchairs.

Results

The results will be presented textually, with flow charts, summary tables, statistical analysis (and meta-analysis where possible) and narrative summaries.

Discussion

We have presented the rationale and design of a systematic review of interventions designed to reduce falls in hospitalised adults. The review will identify effective processes and their elements. The results will inform research into optimal fall risk assessment procedures and effective prevention interventions. It shall also shed light on how best to promote the uptake and implementation of best practice and how to educate patients and clinicians to prevent falls and associated injuries.

Dissemination plan

The findings of this study will be disseminated thr ough the media, peer-reviewed publications and conference, seminar and consumer forum presentation s

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SCS and MM conceived the idea for the study. All authors (SCS, MM, A-MH and DC) were responsible for the study design, the content of the review protocol and all manuscript revisions. SCS drafted the protocol manuscript with input from MM, A-MH and DC. All authors (SCS, MM, A-MH and DC) have read and approved the final protocol manuscript. The corresponding author guarantees that the authorship statement is correct.

Funding: SCS and MM are supported by Healthscope and La Trobe University. A-MH is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. The funders had no role in protocol development.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.WHO. Falls fact sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs344/en/ (updated sep 2016).

- 2.Kassebaum NJ. GBD 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1603–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31460-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vos T. GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1545–602. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AIHW, Pointer S 2015. Aihw PSTrends in hospitalised injury, Australia: 1999–00 to 2012–13. Injury research and statistics series no. 95. Cat. no. INJCAT 171. Canberra: AIHW, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.AIHW. Hospitalisations due to falls by older people, Australia: 2009-10. Injury research and statistics series no. 70. Cat. no. INJCAT 146. Canberra: AIHW, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Healey F, Scobie S, Oliver D, et al. . Falls in English and Welsh hospitals: a national observational study based on retrospective analysis of 12 months of patient safety incident reports. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:424–30. 10.1136/qshc.2007.024695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron ID, Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, et al. . Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD005465 10.1002/14651858.CD005465.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliver D, Daly F, Martin FC, et al. . Risk factors and risk assessment tools for falls in hospital in-patients: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2004;33:122–30. 10.1093/ageing/afh017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Australian Institute Health and Welfare,2014. http://www.aihw.gov.au/injury/falls/

- 10.Center for Disease control and prevention. Falls are leading cause of injury and death in older Americans. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/p0922-older-adult-falls.html.

- 11.Public health matters. https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2014/07/17/the-human-cost-of-falls/

- 12.Morris ME. Preventing falls in older people. BMJ 2012;345:e4919 10.1136/bmj.e4919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris M, Osborne D, Hill K, et al. . Predisposing factors for occasional and multiple falls in older Australians who live at home. Aust J Physiother 2004;50:153–9. 10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60153-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Staggs VS, Mion LC, Shorr RI. Assisted and unassisted falls: different events, different outcomes, different implications for quality of hospital care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2014;40:358–64. 10.1016/S1553-7250(14)40047-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vieira ER, Berean C, Paches D, et al. . Reducing falls among geriatric rehabilitation patients: a controlled clinical trial. Clin Rehabil 2013;27:325–35. 10.1177/0269215512456308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones S, Blake S, Hamblin R, et al. . Reducing Harm from Falls. NZMJ 2016;129:89–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwendimann R, Bühler H, De Geest S, et al. . Characteristics of hospital inpatient falls across clinical departments. Gerontology 2008;54:342–8. 10.1159/000129954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haines T, Kuys SS, Morrison G, et al. . Balance impairment not predictive of falls in geriatric rehabilitation wards. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008;63:523–8. 10.1093/gerona/63.5.523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill AM, McPhail SM, Waldron N, et al. . Fall rates in hospital rehabilitation units after individualised patient and staff education programmes: a pragmatic, stepped-wedge, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:2592–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61945-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris ME, Menz HB, McGinley JL, et al. . A randomized controlled trial to reduce falls in people with Parkinson’s disease. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2015;29:777–85. 10.1177/1545968314565511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haines TP, Hill AM, Hill KD, et al. . Patient education to prevent falls among older hospital inpatients: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:516–24. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shorr RI, Chandler AM, Mion LC, et al. . Effects of an intervention to increase bed alarm use to prevent falls in hospitalized patients: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:692–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-10-201211200-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barker AL, Morello RT, Wolfe R, et al. . 6-PACK programme to decrease fall injuries in acute hospitals: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2016;352:h6781 10.1136/bmj.h6781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sahota O, Drummond A, Kendrick D, et al. . REFINE (REducing Falls in In-patieNt Elderly) using bed and bedside chair pressure sensors linked to radio-pagers in acute hospital care: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2014;43:247–53. 10.1093/ageing/aft155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haines TP, Bell RA, Varghese PN. Pragmatic, cluster randomized trial of a policy to introduce low-low beds to hospital wards for the prevention of falls and fall injuries. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:435–41. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02735.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tzeng HM. Perspectives of staff nurses of the reasons for and the nature of patient-initiated call lights: an exploratory survey study in four USA hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:52 10.1186/1472-6963-10-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tzeng HM, Titler MG, Ronis DL, et al. . The contribution of staff call light response time to fall and injurious fall rates: an exploratory study in four US hospitals using archived hospital data. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:84 10.1186/1472-6963-12-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:11 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins J, Green S, Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.3.0(updated October 2015). eds: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/hospitals/en/

- 34.Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, et al. . Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther 2003;83:713–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Morton NA. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: a demographic study. Aust J Physiother 2009;55:129–33. 10.1016/S0004-9514(09)70043-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M, et al. . Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT): modified delphi study. Phys Ther 2016;96:1514–24. 10.2522/ptj.20150668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M, et al. . Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT): explanation and elaboration statement. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1428–37. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017864supp001.pdf (303KB, pdf)