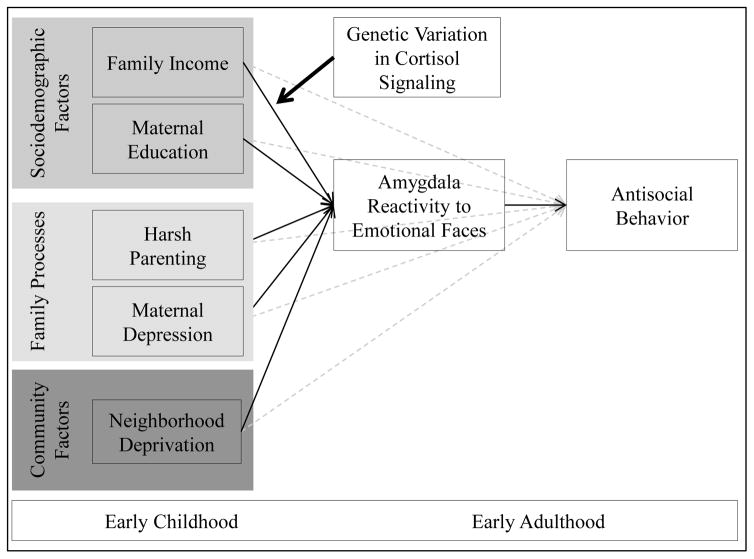

Figure 1. Conceptual model of study aims.

We were guided by a bioecological model of psychopathology (16), process models specifying sociodemographic, family, and community adversities associated with poverty (14,15,53), and neurogenetics and Imaging Gene x Environment interaction models (58,64). We hypothesized that specific adversities present in impoverished contexts put children at differential risk for psychopathology, particularly antisocial behavior in boys, via their effects on brain development and subsequent neural reactivity to emotion and threat. We hypothesized that early adversities would predict antisocial behavior in early adulthood via amygdala reactivity to emotional faces and that this pathway would be stronger among those with genes associated with dysregulated cortisol signaling (24). Specifically, we hypothesized that harsh parenting, as the most proximal factor for young children, would predict greater amygdala reactivity to social signals of threat, distress, and ambiguity, which in turn, would predict antisocial behavior. Moreover, we hypothesized that those with genotypes related to greater cortisol dysregulation would be particularly sensitive to these effects (26–28). Given the need to delineate if these effects are consistent with a diathesis-stress model (i.e., these genes put children at risk for poor outcomes in harsh environments) versus a differential susceptibility model (i.e., these genes mark children who are more sensitive to the environment, for better or worse; 20), we examined the pattern of interactions in Figure 3.