Abstract

Background

Recent studies have implicated inflammatory processes in the pathophysiology of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). C-reactive protein (CRP) is a widely-used measure of peripheral inflammation, but little is known about the genetic and epigenetic factors that influence blood levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) in individuals with PTSD.

Methods

Participants were 286 U.S. military veterans of post-9/11 conflicts (57% with current PTSD). Analyses focused on single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the CRP gene and DNA methylation at cg10636246 in AIM2—a locus recently linked to CRP levels through results from a large-scale epigenome-wide association study.

Results

PTSD was positively correlated with serum CRP levels with PTSD cases more likely to have CRP levels in the clinically-elevated range compared to those without a PTSD diagnosis. Multivariate analyses that controlled for white blood cell proportions, genetic principal components, age and sex, showed this association to be mediated by methylation at the AIM2 locus. rs3091244, a functional SNP in the CRP promoter region, moderated the association between lifetime trauma exposure and current PTSD severity. Analyses also revealed that the top SNPs from the largest genome-wide association study of CRP conducted to date (rs1205 and rs2794520) significantly interacted with PTSD to influence CRP levels.

Conclusions

These findings provide new insights into genetic and epigenetic mechanisms of inflammatory processes in the pathophysiology of PTSD and point to new directions for biomarker identification and treatment development for patients with PTSD.

Findings from recent genetic and blood-biomarker studies provide converging evidence for the role of inflammatory processes in the pathophysiology of PTSD. Plasma and serum studies have found elevated levels of various inflammatory markers in PTSD patients compared to controls and a recent meta-analysis of findings from 20 publications found the diagnosis to be reliably associated with elevated levels of circulating peripheral IL-6, IL-1β, TNFα, and interferon γ (Passos et al., 2015). Genetic association studies have linked inflammation-related genes to risk for PTSD and a network analysis showed that inflammation-related genes, including TNFα and IL-1b, are also involved in regulation of PTSD-associated genes (Pollard et al., 2016). Differential DNA methylation (DNAm) and/or expression of inflammation and immune system genes have also been reported in several studies (Breen et al., 2015; Dehghan et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2011; Zieker et al., 2007).

One of the most extensively validated and widely studied markers of peripheral inflammation is C-reactive protein (CRP), a protein found in blood that responds to inflammatory stimuli by triggering cellular reactions that lead to their clearance. CRP is a highly sensitive inflammatory reactant produced primarily in the liver that increases dramatically in response to relevant stimuli. Though it was long thought to be expressed exclusively in the periphery, recent studies have found CRP in stroke lesions (Di Napoli et al., 2012) and brain tissue from patients with various neurodegenerative diseases (Strang et al., 2012; Yasojima et al., 2000). Other evidence suggests that CRP is produced in the microvessel endothelial cells that form the blood-brain-barrier (Alexandrov et al., 2015) and that peripheral CRP can affect central nervous system via mechanisms of blood-brain barrier disruption (Elwood et al., 2017; Kuhlmann et al., 2009).

Prior studies of blood CRP levels in PTSD samples have yielded mixed results. Passos et al.’s meta-analysis of five studies found no significant group differences overall, but several larger and more recent studies have reported positive associations between CRP and PTSD (Eraly et al., 2014, N > 1,500; Rosen et al., 2017 N > 600), but again, not all findings have been uniform (Baumert et al., 2013; Dennis et al., 2016). Additionally, some studies have found associations between elevated CRP and childhood adversity or adulthood traumatic events (Lin et al., 2016; O’Donovan et al., 2012), suggesting that trauma exposure itself may initiate a pro-inflammatory state. One possible source of variability in findings to date is unmeasured genetic variation in relevant genes, such as the CRP gene (for a review, see Zass et al., 2017). Twin studies of CRP levels have estimated its heritability to be between 25–40% (Dupuis et al., 2005; Pankow et al., 2001; Retterstol et al., 2003) and genome-wide association (GWAS) studies featuring Ns > 10,000 have shown individual CRP polymorphisms to explain substantial individual differences in blood CRP levels (e.g., CRP SNP rs3093099, GG versus TT genotype = 53% increase; CRP SNP rs3091244, AA versus CC = 67% increase; Zacho et al., 2008).

Epigenetic modifications have also been linked to CRP levels, and an epigenome-wide analysis (EWAS) recently found methylation at cg10636246 in the Absent in Melanoma 2 (AIM2) gene, a well-established mediator of the inflammatory response widely implicated in a variety of diseases (Freeman and Ting, 2016), to be the genome-wide strongest predictor of CRP levels in both European (n = 8,863) and African American samples (n = 4,111; Ligthart et al., 2016). In that study, increased DNA methylation at cg10636246 was associated with lower expression of the AIM2 protein and lower CRP levels. These findings suggests that methylation at this locus may function as a mediator of the association between relevant environmental variables, clinical phenotypes, and blood CRP levels. The first aim of this study was to provide a test of this hypothesis by examining associations between PTSD, methylation at cg10636246, and CRP levels.

The second aim was to examine associations between CRP SNPs, PTSD, and blood CRP levels. In the only prior study to have evaluated both CRP levels and CRP SNPs in a PTSD sample, Michopoulos et al. (2015) found CRP SNP rs1130864 to be significantly associated with PTSD in a large urban sample of individuals with histories of trauma exposure (N = 2,692). The same SNP was also associated with CRP levels in a subsample (n = 137) from the same cohort. However, Michopoulos et al. did not report analyses examining the influence of CRP variants on the association between trauma exposure and PTSD (i.e., a gene x environment interaction), nor did they evaluate CRP SNPs as moderators of the strength of the association between PTSD severity and CRP levels.

In this study, we addressed these questions in a sample of veterans with a high prevalence of PTSD by examining CRP SNPs as moderators of (a) the association between trauma exposure and PTSD, and (b) the association between PTSD and blood CRP levels. Based on Michopoulos et al.’s (2015) findings we predicted an association between CRP SNP rs1130864 and both PTSD severity and CRP levels. In addition, given the aforementioned evidence for an independent effect of cg10636246 methylation on CRP levels (Ligthart et al., 2016), we also examined the association between PTSD severity and DNA methylation at this locus and evaluated it as an epigenetic mediator of the association between PTSD and blood CRP levels. Finally, using estimated white blood cell proportions derived from genome-wide DNA methylation data, we examined associations between PTSD, CRP levels, methylation at cg10636246 and the proportion of monocytes, CD4T, CD8T, Natural Killer (NK) and B Cells in blood, all of which have well-established roles in inflammation and immune responses.

Methods

Participants

Participants were US military veterans deployed on post-9/11 operations to Iraq and/or Afghanistan who underwent assessment at the Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders at VA Boston Healthcare System. Exclusion criteria included history of seizures unrelated to head injury, neurologic illness, current psychotic or bipolar disorder, active homicidal or suicidal ideation with intent, and cognitive disorder resulting from a general medical condition other than traumatic brain injury. DNA methylation and clinical data were available for 288 participants. One participant whose CRP level was an outlier (i.e., >5 SDs above the sample mean) and another participant whose cg10636246 probe data failed quality control parameters were excluded, yielding a final sample of 286 participants. Of these, 88.5% were men and their mean age was 32.08 years (SD = 8.358). Most of the sample (72.8%) reported their race as white; the remainder was 15.4% Hispanic or Latino/Latina, 8.6% black, 2.2% Asian, and 1.1% American Indian. More comprehensive information about the demographic and clinical characteristics of this cohort has been published elsewhere (McGlinchey et al., 2017).

Procedure and Measures

The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board. Participants gave written informed consent, had early-morning fasting blood samples drawn for the CRP assay and genetic analysis, and then underwent a comprehensive clinical assessment.

Clinical Assessment

PTSD diagnosis and symptom severity was assessed using a gold standard PTSD structured diagnostic interview, the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) for DSM-IV (Blake et al., 1995). PTSD analyses focused on current (i.e., past month) symptom severity. Dimensional measures of PTSD symptom severity were computed using the sum of the frequency and intensity ratings across all 17 symptoms. Diagnoses were determined by an expert consensus team. Lifetime trauma history was assessed using the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ; Kubany et al., 2000), a self-report measure that queries exposure to 22 types of potentially traumatic events. Analyses reported here focused on the total number of traumas endorsed across the lifespan.

Serum CRP

Blood samples were processed immediately and shipped the same day to a commercial laboratory (Quest Diagnostics, Cambridge, MA) for a nephelometric assay using CRP monoclonal antibodies (analytical sensitivity = .10 mg/dL). Assay procedures were standardized against the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine/Bureau Communautaire de Référence/College of American Pathologists CRP reference preparation. Data were inspected for outliers and, as noted earlier, one observation (raw CRP value > 5.0 mg/dl) was excluded from analysis. The sample mean was .221 mg/dl (SD = .231; range: 0.09 – 1.68 mg/dl). The distribution of raw CRP values was positively-skewed so the data were log-transformed for analysis.

Genomewide SNP and DNA Methylation Analysis

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples. Whole-genome genotypes were obtained by hybridizing DNA samples to Illumina HumanOmni2.5-8 microarrays (Illumina, San Diego, CA). SNP imputation was performed using Impute2 (Howie and Marchini, 2011) and the 1000 genomes reference data (1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al., 2012). Concordance between self-reported and genetically-predicted ancestry was investigated using principal components (PC) analysis as implemented in EIGENSTRAT (Price et al., 2006), using the genotypes of 100,000 common SNPs. The top three PCs from this analysis were retained for use as covariates in the DNAm analyses. Because CRP allele distributions vary considerably across ancestral populations, our CRP SNP analyses were limited to the largest genotype-confirmed ancestrally-homogenous subsample in our cohort (White, non-Hispanics [WNH]; n = 214). As before, we conducted a PC analysis within this subsample to further control for ancestral substructure and used the first 3 WNH PCs as covariates in all CRP SNP analyses.

DNAm analyses were based on the Illumina HumanMethylation450K microarray. Because whole-blood DNAm is an aggregate of all of the various white blood cell (WBC) types, we estimated the proportion monocytes, granulocytes, lymphocytes, CD4 & CD8 T cells, NK cells, and B cells from the methylation data using a well-established statistical procedure called the Houseman method (Houseman et al., 2012; Jaffe and Irizarry, 2014) implemented in the Bio-conductor minfi package (Aryee et al., 2014). These estimates were then included as covariates in all of the DNAm analyses. Other details on genotyping and methylation methods, including data cleaning procedures, elimination of participants, and evaluation of biological sex using X-chromosome homozygosity can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Data Analysis

In the full sample that passed outlier analysis and other quality control filters (n = 286), we first examined the bivariate correlations between current PTSD severity, cg10636246 methylation, CRP levels, and all of the estimated WBC counts. Next, given the observed pattern of associations among the three primary variables of interest, and our a priori hypothesis about AIM2 methylation, we conducted a mediation analysis in the Mplus 7.11 (Muthén and Muthén, 2013) statistical analysis package using the robust maximum likelihood estimator. In this analysis, log CRP values were regressed onto cg10636246 methylation and current PTSD severity while controlling for age, sex, the six WBC estimates, and the first three ancestry PCs. cg10636246 was simultaneously regressed on PTSD, age, sex, the WBCs, and the PCs. The presence of statistical mediation was evaluated by examining the significance of the indirect path from PTSD to CRP via the cg10636246 locus. Model fit was evaluated using standard fit statistics and guidelines (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

CRP SNP analyses were performed within the WNH subgroup (n = 214). Twelve participants were missing either lifetime trauma exposure or PTSD severity data and were excluded from further analysis, yielding a final sample of n = 202 for the WNH genetic association analyses. The first analysis was a linear regression predicting current PTSD severity in which lifetime trauma exposure, age, sex and the three WNH PCs were entered in an initial step, the 11 CRP SNPs (coded additively) were evaluated, in turn, in a second step, and then each trauma exposure × SNP interaction (with the corresponding SNP main effect in the model) was examined in a third step. Significance for SNP main effects and interactions was determined using Monte Carlo null simulation with 10,000 replicates in which the SNPs were randomly permuted between-subjects. We then applied the same approach to test the moderating influence of CRP SNPs on the strength of association between current PTSD severity and CRP levels. Six participants in this subgroup were missing serum CRP data, yielding n = 196 for these analyses.

Results

Bivariate Associations and Mediation Analyses (N = 286)

Table 1 lists the descriptive statistics for, and bivariate correlations between, the primary study variables and covariates. PTSD severity was positively correlated with log CRP (r = .170, p = .004) and a significantly greater proportion of individuals with current PTSD had CRP levels in the clinically-elevated range (Rifai and Ridker, 2003) (> .3 mg/dL; 24.4% versus11.5% for cases and controls, respectively; X2 [1, N = 284] = 7.547, p = .006). PTSD severity was negatively correlated with DNA methylation at cg10636246 (r = −.163, p = .009). cg10636246 was associated with age (r = −.254, p < .001), lower in men than in women (t (257) = −4.313, p < .001), and correlated with all five of the cell type estimates and two of the three ancestral principal components. Log CRP levels were negatively correlated with cg10636246 (r = −.264, p < .001), CD8T (r = −.142, p = .017) and NK cells (r = −.194, p = .001) and were higher in women (mean = 0.343; SD =0.336) than in men (mean = 0.204; SD =0.20; Welch t (34) = −2.281, p = .029)

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations among Variables in the Mediation Analysis

| Mean (SD) | Bivariate Correlations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| PTSD (n=163) | No PTSD (n=123) | PTSD Severity | log CRP | cg10636246 | |

| PTSD Severity | 69.06(19.56)*** | 20.77(14.48)*** | |||

| CRP (mg/dL) | .257(.282)** | .173(.120)** | .170** | ||

| cg10636246 | −1.28(.349) | −1.21(.343) | −.163** | −.264** | |

| Age | 31.860(8.229) | 32.370(8.551) | −.026 | .062 | −.254** |

| Sex (% Male) | 87.10 | 90.20 | .098 | .182** | −.260** |

| CD8T | .059(.034) | .066(.040) | −.049 | −.142* | .206** |

| CD4T | .155(.048) | .159(.049) | −.050 | −.066 | .287** |

| NK | .034(.032)** | .045(.037)** | −.124* | −.194** | −.167** |

| Bcell | .046(.024) | .046(.025) | .093 | .002 | .301** |

| Mono | .093(.026) | .090(.022) | .055 | .020 | −.144* |

| PC1 | −.001(.056) | .004(.062) | .010 | .092 | −.163** |

| PC2 | .003(.063) | −.003(.053) | .046 | −.002 | −.146* |

| PC3 | .003(.061) | −.004(.055) | .030 | −.100 | −.011 |

Note: Asterisks denote independent sample t-tests (cases versus controls, left panel) or bivariate correlation (right panel) that were significant at the * = 0.05 level (2-tailed) or ** = 0.01 level (2-tailed) or *** = .001 level (2-tailed). PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder severity based on Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; CRP = C-reactive protein; NK = natural killer cells; Mono = monocytes; PC = genetic principal component.

Given the pattern of associations between PTSD, cg10636246, CRP levels and our a priori hypothesis about the role DNAm at the AIM2 locus, we then performed a mediation analysis that examined the direct and indirect associations between these three variables controlling for the covariates listed in Table 1 (see Figure 1). The model fit the data well (χ2 = 4.88 [df = 3, n = 286], p = .18; RMSEA = .047, SRMR = .01, CFI = .98, TLI = .88) and showed significant associations between PTSD and cg10636246 (std β = −.15, p = .003) and between cg10636246 and log CRP values (std β = −.28, p < .001). However, in contrast to the significant bivariate association between PTSD and CRP levels described above, in this analysis the association between PTSD and CRP dropped to nonsignificant, indicating that this relationship was mediated by cg10636246. Consistent with this, the test of the indirect effect of PTSD on CRP via cg10636246 (i.e., the mediated path) was statistically significant (std β = .04, p = .017). In total, this model explained 17% of the variance in blood CRP and 31% of the variance in cg10636246 methylation. In addition, there were significant and differential associations between several of the covariates and the dependent variables in this analysis. Specifically, as shown in Figure 1, the significant covariates of cg10636246 were CD4T, B Cells, monocytes, PC1, age and sex. The significant covariates of log CRP were NK and CD8T cells.

Figure 1.

cg10636246 mediates the association between current PTSD severity and serum CRP levels

Results of the structural equation model that examined the direct and indirect associations between PTSD severity, methylation at the AIM2 locus, and CRP levels controlling for age, sex, the six WBC estimates, and the first three ancestry PCs. In contrast to the significant association between PTSD and CRP levels observed in bivariate analyses (i.e., Table 1: r = .170, p = .004), in this model, the association between PTSD and CRP fell to nonsignificant, indicating that their relationship was mediated by cg10636246. Consistent with this, a test of the indirect effect of PTSD on CRP via cg10636246 (i.e., the mediated path) was statistically significant (std β = .04, p = .017).

Analyses of Potential Confounders

In light of prior evidence for an association between cigarette smoking, body mass index (BMI) and elevated CRP (Das, 1985; Kraus et al., 2007), we regressed CRP levels on age, sex, BMI and number of cigarettes smoked per day and found significant associations between CRP levels and female sex (std β = .213, p < .001), BMI (std β = .396, p < .001), and PTSD severity (std β = .121, p = .034) indicating that the PTSD association withstood correction for BMI and smoking. Similarly, when we regressed cg10636246 on the same variables, age (std β = −.238, p < .001), sex (std β = −.260, p < .001), BMI (std β = −.134, p < .028), and PTSD severity (std β = −.142, p = .021), were all significant. We also examined bivariate associations between lifetime trauma exposure and both CRP (r = .064, p = .282) and DNAm at cg1063624 (r = −.149, p = .017). Given the latter evidence for an association between trauma exposure and DNAm at this locus, we then regressed cg1063624 onto trauma exposure, PTSD, and each of the covariates. In this model, PTSD remained a significant predictor of cg1063624 (std β = −.138, p = .025), while trauma was not (std β = −.022, p = .719) suggesting that the bivariate association with trauma was better accounted for by PTSD. Finally, given the high co-occurrence of PTSD and history of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) in veterans of post-9/11 deployments, we also examined the bivariate associations between various indices of mTBI and both cg1063624 and CRP levels but found no significant associations (all ps > .3).

Genetic Association Analyses (White Non-Hispanic Subsample; n = 202)

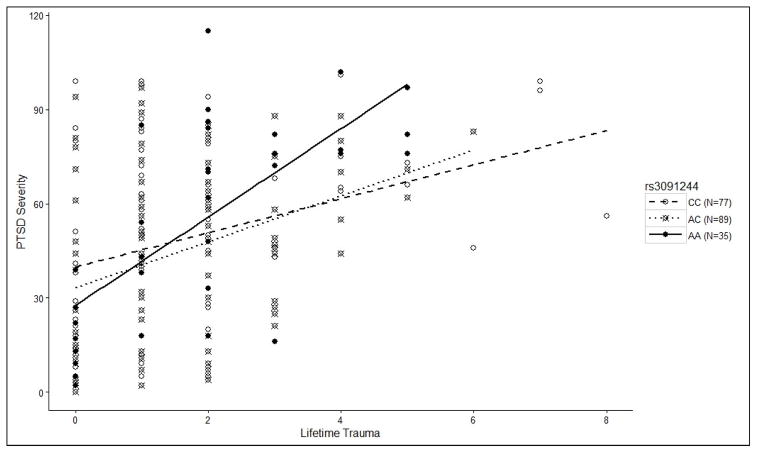

The analysis examining the 11 CRP SNPs as moderators of the association between lifetime trauma exposure and PTSD severity revealed a main effect of trauma exposure (unstandardized β = 7.62, p = 1×10−9), a main effect of PC3 (unstandardized β = −68.17, p = .013), but no significant SNP main effects or other covariate effects. However, there was a multiple testing-corrected significant trauma x rs3091244 interaction (β = 4.26, p = .006; pcorrected = .015; see Figure 2 and Table 2) the decomposition of which revealed that the correlation between trauma exposure and PTSD was significantly stronger for homozygote (2 copy) carriers of the minor allele ([n = 35]; r = .681, p < .001) than for carriers of the major allele ([1 copy, n = 89] r = .364, p < .001; [2 copies, n = 77] r = .323, p = .004)1. (Lists of all nominally-significant SNP effects from this analysis and the next one reported below are available in Supplementary Tables 1&2).

Figure 2.

CRP SNP rs3091244 Moderates the Association Between Lifetime Trauma Exposure and PTSD Severity

Scatterplot depicting the influence of rs3091244 on the relationship between trauma exposure and PTSD severity. This association was significantly stronger for homozygote (2 copy) carriers of the minor allele ([n = 35]; r = .681, p < .001) than for carriers of the major allele ([1 copy, n = 89] r = .364, p < .001; [2 copies, n = 77] r = .323, p = .004).

Table 2.

Results of the Analysis Examining rs3091244 as a Moderator of the Association between Lifetime Trauma Exposure and Current PTSD Severity

| Block/Variable | R2 | Δ R2 | B | SE | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1 (Covariates) | .043 | .043 | .127 | |||

| PC1 | 6.055 | 29.730 | .014 | .839 | ||

| PC2 | 43.539 | 30.017 | .103 | .149 | ||

| PC3 | −65.289 | 29.801 | −.156 | .030 | ||

| Age | −.261 | .251 | −.074 | .301 | ||

| Sex | 3.818 | 7.236 | .038 | .598 | ||

| Block 2 (Main effects) | .211 | .168 | .000 | |||

| Trauma | 7.536 | 1.185 | .417 | <.001 | ||

| rs3091244 | 2.516 | 2.600 | .062 | .334 | ||

| Block 3 (Interaction) | .241 | .030 | .006 | |||

| rs3091244 x Trauma | 4.259 | 1.545 | 2.756 | .006 |

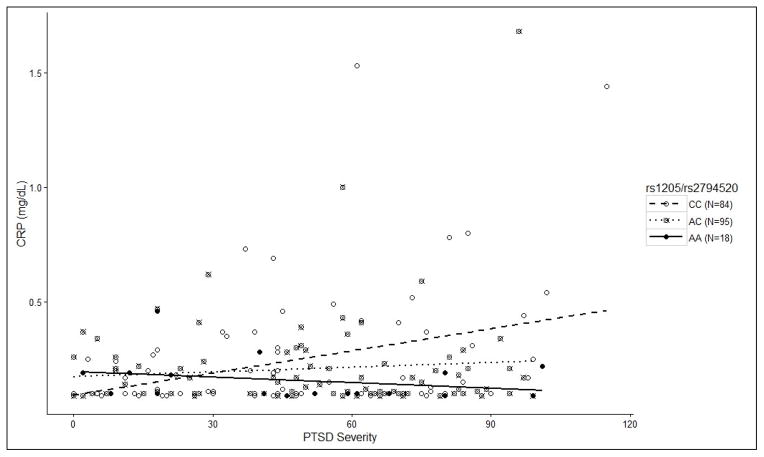

Finally, the PTSD severity x CRP SNP analysis using serum CRP as the dependent variable revealed a significant main effect of PTSD severity (unstandardized β =0.0017, p = .021) and significant PTSD x SNP interactions involving two SNPs in perfect linkage disequilibrium: rs1205 (unstandardized β = −.0033, p = .002, pcorrected = .018) and rs2794520 (unstandardized β = −.0032, p = .003, pcorrected = .022; see Figures 3&4 and Table 3). As before, we decomposed the PTSD x SNP interactions by examining the correlation between PTSD and CRP levels for each genotype separately and found that the main effect of PTSD severity on CRP was driven exclusively by those who were homozygous for the major allele of both SNPs (CC [n = 84]; r = .364, p = .001; AC [n = 94] r = .022, p = .834; AA [n = 18] r = −.293, p = .239). Furthermore, among participants with current PTSD, there was an additive relationship between the number of copies of the major allele and the probability of having a clinically-significant elevation of CRP (> .3 mg/dL; 0 copies = 0%, 1 copy = 16.9%, 2 copies = 37.8%; χ2 = 9.897, p = .007). This pattern was not evident among those without a current PTSD diagnosis (0 copies = 14.3%, 1 copy = 16.7%, 2 copies = 5.3%; χ2 = 2.52, p = .285).

Figure 3.

CRP SNPs rs1205 & rs2794520 Moderate the Association Between PTSD severity and Serum CRP Levels

Scatterplot depicting the influence of the two SNPs in perfect LD (rs1205 & rs2794520) that moderated the association PTSD severity and serum CRP level. Decomposition of the interaction showed that the main effect of PTSD severity on CRP was driven exclusively by those who were homozygous for the major allele of both SNPs (CC [n = 84]; r = .364, p = .001; AC [n = 94] r = .022, p = .834; AA [n = 18] r = −.293, p = .239).

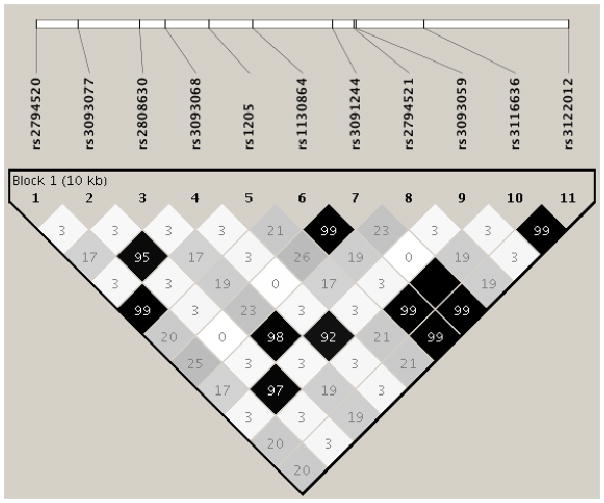

Figure 4.

Linkage disequilibrium between the 11 CRP SNPs.

Note: From 1000 genomes-Phase 3, EUR sample (1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al., 2012)

Table 3.

Results of the Analysis examining rs1205/rs2794520 as a Moderator of the Association between Current PTSD Severity and CRP Levels

| Block/Variable | R2 | Δ R2 | B | SE | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1 | .018 | .018 | .632 | |||

| PC1 | .184 | .301 | .044 | .541 | ||

| PC2 | −.182 | .299 | −.044 | .544 | ||

| PC3 | −.012 | .301 | −.003 | .969 | ||

| Age | .000 | .003 | −.011 | .875 | ||

| Sex | .122 | .074 | .120 | .102 | ||

| Block 2 | .058 | .040 | .020 | |||

| PTSD severity | .002 | .001 | .176 | .016 | ||

| SNP | −.050 | .032 | −.112 | .117 | ||

| Block 3 | .104 | .047 | .002 | |||

| SNP x PTSD severity | −.003 | .001 | −.472 | .002 |

Discussion

This study examined associations between PTSD, DNA methylation at a CRP-associated locus in the AIM2 gene, CRP SNPs, and serum CRP levels in a sample of veterans with a high prevalence of PTSD. Findings provide new evidence for the involvement of peripheral inflammation in the pathophysiology of PTSD and shed new light on the genetic and epigenetic mechanisms involved. Using the top DNAm locus from Ligthart et al.’s (2016) recent 10K+ subject epigenome-wide association study of CRP levels, we found that the relationship between current PTSD severity and serum CRP was statistically mediated by methylation at this locus. cg10636246 is located near the transcription start site of AIM2, a well-known gene that transcribes an interferon-inducible protein and plays a key role in activating the innate immune response (Fernandes-Alnemri et al., 2009). Ligthart et al. (2016) showed that decreased methylation at cg10636246 was associated with both increased expression of AIM2 and elevated CRP levels. Though inferences about the causal direction of associations among these variables should be considered tentative given the cross-sectional nature of both studies, together they raise the possibility that PTSD promotes elevated CRP via loss of methylation at this locus.

The use of estimated white blood cell counts as covariates of cg10636246 and CRP levels in these analyses provided control for a variety of cellular factors that could potentially confound the observed associations between PTSD, DNA methylation, and serum CRP levels. Analyses revealed significant negative associations between NK cells and current PTSD severity (in bivariate analyses) and inverse associations between NK and CD8T cell counts and CRP levels (in both bivariate and multivariate models). NK cells are part of the innate immune system and critical for responding to virus and cancer cells via direct cytotoxic activity (Campbell and Hasegawa, 2013). Prior studies have reported inconsistent associations between PTSD and cells of this type, but methodological differences in cell type measurement complicate the interpretation of findings across studies (Gotovac et al., 2010; Kawamura et al., 2001; Laudenslager et al., 1998). In one study that differentiated between the various NK cell sub-populations, Bersani et al. (2016) found PTSD to be positively associated with cytotoxicity of the rarer NK subset termed CD56−CD16+, but negatively associated with cytotoxicity of the CD56dimCD16+ cell type, which comprises the majority (~90%) of NK cells. Thus, the findings of our study point to an association between PTSD and reduced availability of the more common types of NK cells.

Several caveats about the white blood cell findings should be kept in mind. DNA methylation profiles differ across cell types and the continuous percent methylation value at a given locus in blood represents the average methylation state at that locus across multiple cells. To address this, our analyses included estimates of cell proportions indirectly derived from genome-wide DNA methylation data, as opposed to direct measures of cell counts derived from laboratory assays. The proportional nature of these variables complicates interpretation of findings because observed patterns of association for a given cell type are, by definition, dependent on estimated levels of the other types. It is also conceivable that residual variance attributable to unmeasured cell types not estimated by the Houseman method may have influenced our results. One counter-argument to these concerns, however, is that the method we used to estimate cell proportion is well-validated (Houseman et al., 2012; Jaffe and Irizarry, 2014) and yields correlations with directly-measured cell counts in the range of .7 – .8 (Kaushal et al., 2017). From another perspective, Holbrook et al. (2017) recently proposed that cellular heterogeneity should be considered not merely a technical confounder to be removed from blood-based DNA methylation estimates, but sensitive measures of cell fate in their own right that are potentially relevant to disease prediction, prognosis, and clinical outcomes.

Examination of potential confounders (cigarette smoking and BMI) and standard covariates (age and sex) revealed that while BMI and sex were both associated with CRP and cg10636246, PTSD explained a significant proportion of the variance in both outcomes controlling for these other variables. The positive associations between CRP, female sex, and BMI are well-established in the literature. The covariate associations with methylation at cg10636246 (though more novel and opposite in direction) were similar to that for CRP. Furthermore, the BMI association replicates a finding from the Ligthart et al. (2016) EWAS and points to a possible role for AIM2 methylation in the link between PTSD, inflammation, and cardiometabolic disease.

Results of the CRP SNP analyses provided additional insight into the complex relationship between PTSD and circulating CRP levels. First, our PTSD association analysis revealed a significant SNP x lifetime trauma severity interaction involving rs3091244 with homozygote carriers of the minor allele (AA) showing a significantly stronger relationship between trauma exposure and current PTSD severity compared to carriers of the major allele. rs3091244 (aka 1400 or −390 in the literature) is a functional tri-allelic (A/C/T) SNP that influences CRP promoter activity and has been associated with CRP levels in both healthy adults (Szalai et al., 2005) and trauma-exposed individuals (Michopoulos et al., 2015). rs3091244 is in high LD with rs1130864 (R2 = .99 in 1000 Genomes; see Figure 4) a SNP recently implicated in both risk for major depression (Almeida et al., 2009) and PTSD (Michopoulos et al., 2015). In both of those studies, as in this one, carriers of the minor allele were at elevated risk for the development of psychopathology.

Analyses also identified a pair of CRP SNPs in perfect LD (rs1205 and rs2794520) that moderated the association between PTSD severity and serum CRP levels such that participants with PTSD who were homozygous for the major allele had elevated levels of CRP. rs1205 and rs2794520 have well-established associations with CRP levels; Dehghan et al.’s (2011) empirical meta-analysis of CRP GWAS studies based on over 80K subjects found rs2794520 to be the genome-wide top CRP-associated SNP. rs1205 (aka 1846 G>A) has a more extensive publication history, due to its earlier discovery. Its major allele has been linked to elevated CRP levels and increased risk for various adverse cardiometabolic outcomes (Hernandez-Diaz et al., 2015; Oki et al., 2016; Todendi et al., 2015; Todendi et al., 2016). Furthermore, Ancelin et al. (2015) reported that women who were homozygous for the rs1205 minor allele had lower levels of CRP but were at increased risk for depression. Almeida et al. (2009) found a similar pattern of results in a sample of elderly men and hypothesized that the rs1205 minor allele reduces the effectiveness of the body’s response to immunological threat and/or injury by blunting the CRP response. This, they reasoned, could perpetuate immune and inflammatory reactions and eventually give rise to the expression of depression symptoms through alterations of neurotransmitters, hormones, and other mechanisms.

Extending this hypothesis to the context of PTSD, the implication is that individuals who mount an insufficient CRP response to the pro-inflammatory state initiated by acute traumatic stress and/or chronic PTSD, and as a result fail to restore cellular homeostasis, are at increased risk for the development of a persistent or chronic inflammatory state. Several molecular mechanisms linking PTSD to chronic inflammation have been identified including alterations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, chronic sleep disturbance, and oxidative stress (for a review, see Miller et al. [in press]). One treatment implication which follows is that raising the serum concentration of CRP in PTSD patients who are homozygotic for the rs1205/rs2794520 minor allele could potentially confer therapeutic benefits for these individuals. Conversely, our finding of an additive relationship between the number of copies of the rs1205/rs2794520 major allele and the probability of having clinically-elevated CRP levels suggests that CRP genotyping could be used to identify PTSD patients at the greatest risk for the development of secondary cardiometabolic conditions (Koenen et al., 2017; Wolf et al., 2016).

Findings of this study should be considered relative to several methodological limitations. First, the modest size and homogenous composition of the sample may limit the generalizability of findings to trauma populations with a different composition of ancestry, sex, or trauma type. Second, the CRP assay used in this study had a lower limit of detection of only .10mg/dL, not the “high-sensitivity” assay that offers a lower limit of .02mg/dL. Forty-one participants (14.3%) had raw CRP scores below our lower limit of detection. This likely introduced a floor-effect that may have attenuated the magnitude of observed associations, but would not be expected to yield false-positive results. Third, the cross-sectional nature of the study precludes strong causal inferences about the nature of the associations between the primary variables of interest. However, as noted earlier, Lightart et al.’s (2016) findings support the biological plausibility of AIM2 methylation as a mediator of the association between PTSD and CRP. Finally, given the size of our sample, we limited our genetic analyses to one gene (CRP) and one methylation locus on the basis of strong a priori evidence for their relevance to CRP. Other genetic and epigenetic loci that we did not interrogate in this study are undoubtedly involved. Finally, because the scope of this study was limited to analysis of DNAm and CRP levels in blood, we were unable to examine tissue-specific methylation or expression changes in the brain or other relevant organs (such as the liver where CRP is primarily produced).

To conclude, study findings provide important new insights in to the genetic and epigenetic mechanisms of the association between traumatic stress and peripheral inflammation and identify AIM2 DNA methylation, CRP gene variation, and CRP levels as potentially useful targets for future PTSD biomarker research and treatment development.

Supplementary Material

This study examined genetic factors that influence CRP levels in patients with PTSD.

PTSD was positively correlated with plasma CRP levels.

The relationship between PTSD and CRP was mediated by DNA methylation of AIM2.

CRP SNPs moderated the association between PTSD and CRP levels.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH grant R21MH102834 “Neuroimaging Genetics of PTSD” to Mark Miller and the Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders (TRACTS), a VA Rehabilitation Research and Development Traumatic Brain Injury National Network Research Center (B9254-C). Additional support was provided by NIA grant R03AG051877 to Erika Wolf and by the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE) to Erika Wolf as administered by U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Research and Development (PECASE 2013A). This research was also supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Pharmacogenomics Analysis Laboratory, Research and Development Service, Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Footnotes

These ns sum to 201 rather than 202 because one participant’s data for this SNP failed QC.

Disclosures

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. All authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, Kang HM, Marth GT, McVean GA. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov PN, Kruck TP, Lukiw WJ. Nanomolar aluminum induces expression of the inflammatory systemic biomarker C-reactive protein (CRP) in human brain microvessel endothelial cells (hBMECs) J Inorg Biochem. 2015;152:210–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida OP, Norman PE, Allcock R, van Bockxmeer F, Hankey GJ, Jamrozik K, Flicker L. Polymorphisms of the CRP gene inhibit inflammatory response and increase susceptibility to depression: the Health in Men Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1049–1059. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancelin ML, Farre A, Carriere I, Ritchie K, Chaudieu I, Ryan J. C-reactive protein gene variants: independent association with late-life depression and circulating protein levels. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e499. doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H, Ladd-Acosta C, Feinberg AP, Hansen KD, Irizarry RA. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1363–1369. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumert J, Lukaschek K, Kruse J, Emeny RT, Koenig W, von Kanel R, Ladwig KH investigators K. No evidence for an association of posttraumatic stress disorder with circulating levels of CRP and IL-18 in a population-based study. Cytokine. 2013;63:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersani FS, Wolkowitz OM, Milush JM, Sinclair E, Eppling L, Aschbacher K, Lindqvist D, Yehuda R, Flory J, Bierer LM, Matokine I, Abu-Amara D, Reus VI, Coy M, Hough CM, Marmar CR, Mellon SH. A population of atypical CD56(−)CD16(+) natural killer cells is expanded in PTSD and is associated with symptom severity. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;56:264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM. The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen MS, Maihofer AX, Glatt SJ, Tylee DS, Chandler SD, Tsuang MT, Risbrough VB, Baker DG, O’Connor DT, Nievergelt CM, Woelk CH. Gene networks specific for innate immunity define post-traumatic stress disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:1538–1545. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KS, Hasegawa J. Natural killer cell biology: an update and future directions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:536–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das I. Raised C-reactive protein levels in serum from smokers. Clin Chim Acta. 1985;153:9–13. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(85)90133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghan A, Dupuis J, Barbalic M, Bis JC, Eiriksdottir G, Lu C, Pellikka N, Wallaschofski H, Kettunen J, Henneman P, Baumert J, Strachan DP, Fuchsberger C, Vitart V, Wilson JF, Pare G, Naitza S, Rudock ME, Surakka I, de Geus EJ, Alizadeh BZ, Guralnik J, Shuldiner A, Tanaka T, Zee RY, Schnabel RB, Nambi V, Kavousi M, Ripatti S, Nauck M, Smith NL, Smith AV, Sundvall J, Scheet P, Liu Y, Ruokonen A, Rose LM, Larson MG, Hoogeveen RC, Freimer NB, Teumer A, Tracy RP, Launer LJ, Buring JE, Yamamoto JF, Folsom AR, Sijbrands EJ, Pankow J, Elliott P, Keaney JF, Sun W, Sarin AP, Fontes JD, Badola S, Astor BC, Hofman A, Pouta A, Werdan K, Greiser KH, Kuss O, Meyer zu Schwabedissen HE, Thiery J, Jamshidi Y, Nolte IM, Soranzo N, Spector TD, Volzke H, Parker AN, Aspelund T, Bates D, Young L, Tsui K, Siscovick DS, Guo X, Rotter JI, Uda M, Schlessinger D, Rudan I, Hicks AA, Penninx BW, Thorand B, Gieger C, Coresh J, Willemsen G, Harris TB, Uitterlinden AG, Jarvelin MR, Rice K, Radke D, Salomaa V, Willems van Dijk K, Boerwinkle E, Vasan RS, Ferrucci L, Gibson QD, Bandinelli S, Snieder H, Boomsma DI, Xiao X, Campbell H, Hayward C, Pramstaller PP, van Duijn CM, Peltonen L, Psaty BM, Gudnason V, Ridker PM, Homuth G, Koenig W, Ballantyne CM, Witteman JC, Benjamin EJ, Perola M, Chasman DI. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in >80 000 subjects identifies multiple loci for C-reactive protein levels. Circulation. 2011;123:731–738. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.948570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis PA, Weinberg JB, Calhoun PS, Watkins LL, Sherwood A, Dennis MF, Beckham JC. An investigation of vago-regulatory and health-behavior accounts for increased inflammation in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychosom Res. 2016;83:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Napoli M, Godoy DA, Campi V, Masotti L, Smith CJ, Parry Jones AR, Hopkins SJ, Slevin M, Papa F, Mogoanta L, Pirici D, Popa Wagner A. C-reactive protein in intracerebral hemorrhage: time course, tissue localization, and prognosis. Neurology. 2012;79:690–699. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318264e3be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis J, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Massaro JM, Wilson PW, Lipinska I, Corey D, Vita JA, Keaney JF, Jr, Benjamin EJ. Genome scan of systemic biomarkers of vascular inflammation in the Framingham Heart Study: evidence for susceptibility loci on 1q. Atherosclerosis. 2005;182:307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwood E, Lim Z, Naveed H, Galea I. The effect of systemic inflammation on human brain barrier function. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eraly SA, Nievergelt CM, Maihofer AX, Barkauskas DA, Biswas N, Agorastos A, O’Connor DT, Baker DG Marine Resiliency Study T. Assessment of plasma C-reactive protein as a biomarker of posttraumatic stress disorder risk. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:423–431. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yu JW, Datta P, Wu J, Alnemri ES. AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature. 2009;458:509–513. doi: 10.1038/nature07710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman LC, Ting JP. The pathogenic role of the inflammasome in neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurochem. 2016;136(Suppl 1):29–38. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotovac K, Vidovic A, Vukusic H, Krcmar T, Sabioncello A, Rabatic S, Dekaris D. Natural killer cell cytotoxicity and lymphocyte perforin expression in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Diaz Y, Tovilla-Zarate CA, Juarez-Rojop I, Banos-Gonzalez MA, Torres-Hernandez ME, Lopez-Narvaez ML, Yanez-Rivera TG, Gonzalez-Castro TB. The role of gene variants of the inflammatory markers CRP and TNF-alpha in cardiovascular heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:11958–11984. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook JD, Huang RC, Barton SJ, Saffery R, Lillycrop KA. Is cellular heterogeneity merely a confounder to be removed from epigenome-wide association studies? Epigenomics. 2017 doi: 10.2217/epi-2017-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houseman EA, Accomando WP, Koestler DC, Christensen BC, Marsit CJ, Nelson HH, Wiencke JK, Kelsey KT. DNA methylation arrays as surrogate measures of cell mixture distribution. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howie B, Marchini J. 2011 IMPUTE2. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AE, Irizarry RA. Accounting for cellular heterogeneity is critical in epigenome-wide association studies. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R31. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal A, Zhang H, Karmaus WJJ, Ray M, Torres MA, Smith AK, Wang SL. Comparison of different cell type correction methods for genome-scale epigenetics studies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2017;18:216. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1611-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura N, Kim Y, Asukai N. Suppression of cellular immunity in men with a past history of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:484–486. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen KC, Sumner JA, Gilsanz P, Glymour MM, Ratanatharathorn A, Rimm EB, Roberts AL, Winning A, Kubzansky LD. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiometabolic disease: improving causal inference to inform practice. Psychol Med. 2017;47:209–225. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716002294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus VB, Stabler TV, Luta G, Renner JB, Dragomir AD, Jordan JM. Interpretation of serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels for cardiovascular disease risk is complicated by race, pulmonary disease, body mass index, gender, and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:966–971. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Haynes SN, Leisen MB, Owens JA, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, Burns K. Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 2000;12:210–224. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann CR, Librizzi L, Closhen D, Pflanzner T, Lessmann V, Pietrzik CU, de Curtis M, Luhmann HJ. Mechanisms of C-reactive protein-induced blood-brain barrier disruption. Stroke. 2009;40:1458–1466. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.535930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudenslager ML, Aasal R, Adler L, Berger CL, Montgomery PT, Sandberg E, Wahlberg LJ, Wilkins RT, Zweig L, Reite ML. Elevated cytotoxicity in combat veterans with long-term post-traumatic stress disorder: preliminary observations. Brain Behav Immun. 1998;12:74–79. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1997.0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligthart S, Marzi C, Aslibekyan S, Mendelson MM, Conneely KN, Tanaka T, Colicino E, Waite LL, Joehanes R, Guan W, Brody JA, Elks C, Marioni R, Jhun MA, Agha G, Bressler J, Ward-Caviness CK, Chen BH, Huan T, Bakulski K, Salfati EL, Fiorito G, Wahl S, Schramm K, Sha J, Hernandez DG, Just AC, Smith JA, Sotoodehnia N, Pilling LC, Pankow JS, Tsao PS, Liu C, Zhao W, Guarrera S, Michopoulos VJ, Smith AK, Peters MJ, Melzer D, Vokonas P, Fornage M, Prokisch H, Bis JC, Chu AY, Herder C, Grallert H, Yao C, Shah S, McRae AF, Lin H, Horvath S, Fallin D, Hofman A, Wareham NJ, Wiggins KL, Feinberg AP, Starr JM, Visscher PM, Murabito JM, Kardia SL, Absher DM, Binder EB, Singleton AB, Bandinelli S, Peters A, Waldenberger M, Matullo G, Schwartz JD, Demerath EW, Uitterlinden AG, van Meurs JB, Franco OH, Chen YI, Levy D, Turner ST, Deary IJ, Ressler KJ, Dupuis J, Ferrucci L, Ong KK, Assimes TL, Boerwinkle E, Koenig W, Arnett DK, Baccarelli AA, Benjamin EJ, Dehghan A Investigators WE, Disease C.e.o.C.H. DNA methylation signatures of chronic low-grade inflammation are associated with complex diseases. Genome Biol. 2016;17:255. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1119-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JE, Neylan TC, Epel E, O’Donovan A. Associations of childhood adversity and adulthood trauma with C-reactive protein: A cross-sectional population-based study. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;53:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, Fortier CB. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: The TRACTS longitudinal prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017 doi: 10.1002/mpr.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michopoulos V, Rothbaum AO, Jovanovic T, Almli LM, Bradley B, Rothbaum BO, Gillespie CF, Ressler KJ. Association of CRP genetic variation and CRP level with elevated PTSD symptoms and physiological responses in a civilian population with high levels of trauma. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:353–362. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Lin AP, Wolf EJ, Miller DR. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and neuroprogression in PTSD. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000167. [in press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus 7.11. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donovan A, Neylan TC, Metzler T, Cohen BE. Lifetime exposure to traumatic psychological stress is associated with elevated inflammation in the Heart and Soul Study. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oki E, Norde MM, Carioca AA, Ikeda RE, Souza JM, Castro IA, Marchioni DM, Fisberg RM, Rogero MM. Interaction of SNP in the CRP gene and plasma fatty acid profile in inflammatory pattern: A cross-sectional population-based study. Nutrition. 2016;32:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankow JS, Folsom AR, Cushman M, Borecki IB, Hopkins PN, Eckfeldt JH, Tracy RP. Familial and genetic determinants of systemic markers of inflammation: the NHLBI family heart study. Atherosclerosis. 2001;154:681–689. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00586-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos IC, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Costa LG, Kunz M, Brietzke E, Quevedo J, Salum G, Magalhaes PV, Kapczinski F, Kauer-Sant’Anna M. Inflammatory markers in post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:1002–1012. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00309-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard HB, Shivakumar C, Starr J, Eidelman O, Jacobowitz DM, Dalgard CL, Srivastava M, Wilkerson MD, Stein MB, Ursano RJ. “Soldier’s Heart”: A Genetic Basis for Elevated Cardiovascular Disease Risk Associated with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Front Mol Neurosci. 2016;9:87. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retterstol L, Eikvar L, Berg K. A twin study of C-Reactive Protein compared to other risk factors for coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2003;169:279–282. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifai N, Ridker PM. Population distributions of C-reactive protein in apparently healthy men and women in the United States: implication for clinical interpretation. Clin Chem. 2003;49:666–669. doi: 10.1373/49.4.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen RL, Levy-Carrick N, Reibman J, Xu N, Shao Y, Liu M, Ferri L, Kazeros A, Caplan-Shaw CE, Pradhan DR, Marmor M, Galatzer-Levy IR. Elevated C-reactive protein and posttraumatic stress pathology among survivors of the 9/11 World Trade Center attacks. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;89:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AK, Conneely KN, Kilaru V, Mercer KB, Weiss TE, Bradley B, Tang Y, Gillespie CF, Cubells JF, Ressler KJ. Differential immune system DNA methylation and cytokine regulation in post-traumatic stress disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156B:700–708. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang F, Scheichl A, Chen YC, Wang X, Htun NM, Bassler N, Eisenhardt SU, Habersberger J, Peter K. Amyloid plaques dissociate pentameric to monomeric C-reactive protein: a novel pathomechanism driving cortical inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease? Brain Pathol. 2012;22:337–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalai AJ, Wu J, Lange EM, McCrory MA, Langefeld CD, Williams A, Zakharkin SO, George V, Allison DB, Cooper GS, Xie F, Fan Z, Edberg JC, Kimberly RP. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the C-reactive protein (CRP) gene promoter that affect transcription factor binding, alter transcriptional activity, and associate with differences in baseline serum CRP level. J Mol Med (Berl) 2005;83:440–447. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0658-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todendi PF, Klinger EI, Ferreira MB, Reuter CP, Burgos MS, Possuelo LG, Valim AR. Association of IL-6 and CRP gene polymorphisms with obesity and metabolic disorders in children and adolescents. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2015;87:915–924. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201520140364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todendi PF, Possuelo LG, Klinger EI, Reuter CP, Burgos MS, Moura DJ, Fiegenbaum M, Valim AR. Low-grade inflammation markers in children and adolescents: Influence of anthropometric characteristics and CRP and IL6 polymorphisms. Cytokine. 2016;88:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Sadeh N, Leritz EC, Logue MW, Stoop TB, McGlinchey R, Milberg W, Miller MW. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder as a Catalyst for the Association Between Metabolic Syndrome and Reduced Cortical Thickness. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80:363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasojima K, Schwab C, McGeer EG, McGeer PL. Human neurons generate C-reactive protein and amyloid P: upregulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2000;887:80–89. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02970-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacho J, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Jensen JS, Grande P, Sillesen H, Nordestgaard BG. Genetically elevated C-reactive protein and ischemic vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1897–1908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zass LJ, Hart SA, Seedat S, Hemmings SM, Malan-Muller S. Neuroinflammatory genes associated with post-traumatic stress disorder: implications for comorbidity. Psychiatr Genet. 2017;27:1–16. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0000000000000143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieker J, Zieker D, Jatzko A, Dietzsch J, Nieselt K, Schmitt A, Bertsch T, Fassbender K, Spanagel R, Northoff H, Gebicke-Haerter PJ. Differential gene expression in peripheral blood of patients suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:116–118. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.