Abstract

Diaphragmatic eventration is an uncommon condition, usually discovered incidentally in asymptomatic patients. Even in symptomatic patients, the diagnosis can be challenging and should be considered among the differential diagnoses of diaphragmatic hernia. The correct diagnosis can often only be made in surgery. We describe the case of a 31-year-old patient with diaphragmatic eventration that was misdiagnosed as a recurrent congenital diaphragmatic hernia and review the corresponding literature.

Keywords: Eventration, Diaphragmatic Hernia, Diaphragmatic Plication

Diaphragmatic eventration is the partial or total replacement of the diaphragm muscle with fibroelastic tissue1 while maintaining the diaphragmatic attachments to the sternum, ribs and lumbar spine. It is a rare entity affecting approximately 0.05% of the general population1 and usually presents as an incidental finding on imaging. Diaphragmatic eventration can be congenital or acquired.2 Eventration is often severe in infants, resulting in respiratory distress, but may be asymptomatic in adults or present with mild symptoms including chest pain, shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, palpitations, pneumonia or gastrointestinal reflux. Diagnosing diaphragmatic eventration can be challenging, even for an experienced physician. Further distinguishing this diagnosis from other pathologies on imaging, such as paraoesophageal hernia, is often difficult and the correct diagnosis can only be made at surgery.3 We present a case of diaphragmatic eventration that was misdiagnosed as a recurrent congenital diaphragmatic hernia and review the corresponding literature.

Case history

A 31-year-old man of African descent (a non-smoker with a past medical history of hypertension) presented with a recurrent congenital diaphragmatic hernia that had been repaired at a different hospital two months earlier. Prior to his surgery, he presented with palpitations, shortness of breath and chest pain. Electrocardiography demonstrated atrial fibrillation. Chest radiography showed a large left congenital diaphragmatic hernia with mediastinal shift and tracheal deviation (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) revealed herniation of the splenic flexure into the chest with massive dilation and mediastinal shift (Figures 2 and 3). This was confirmed on barium enema. A colonoscope was unable to traverse the splenic flexure. The patient had had recent diarrhea suggesting possible colonic obstruction with overflow diarrhea.

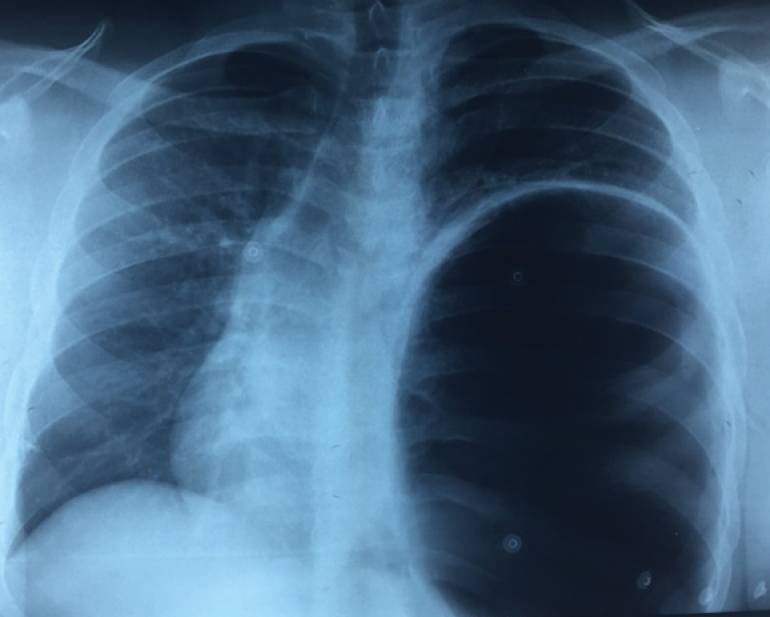

Figure 1.

Plain radiography showing a large left diaphragmatic hernia with mediastinal shift

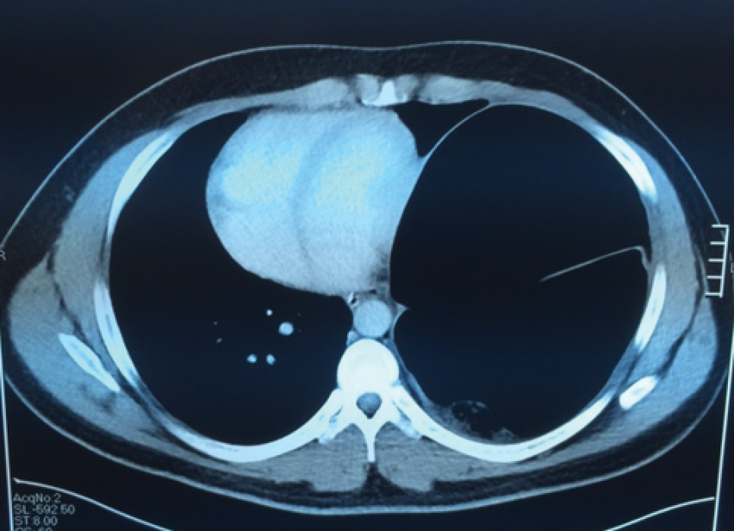

Figure 2.

Computed tomography demonstrating a large left diaphragmatic hernia with mediastinal shift

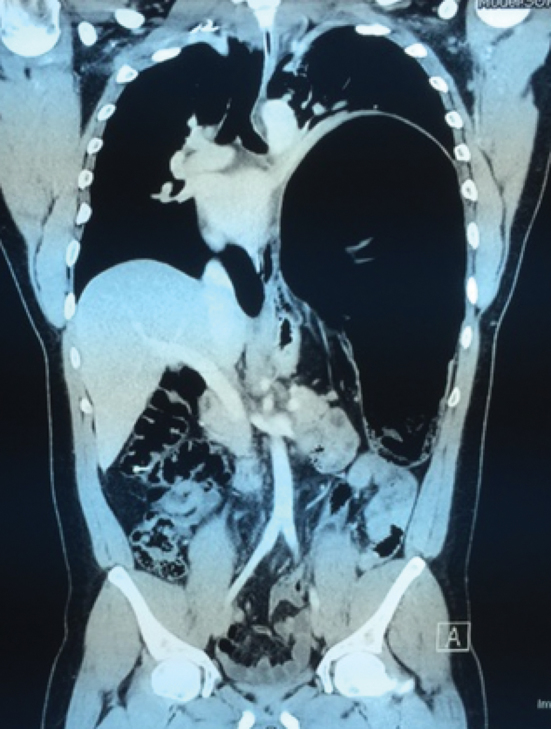

Figure 3.

Coronal view demonstrating dilated colon within the hernia

At his local hospital, the patient underwent laparoscopy for repair of a supposed large left congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Intraoperatively, only a small remnant of the left diaphragm was identified. The splenic flexure, small bowel and spleen were reduced, and a large coated polypropylene mesh was tacked to the posterior chest wall and sutured medially to the diaphragm remnant. A chest tube was placed. Daily chest radiographs were obtained and no recurrence was demonstrated until postoperative day 8, when plain radiography showed recurrence of the left diaphragmatic hernia. He was subsequently discharged.

The patient presented to Mount Sinai Hospital in no acute distress but with dyspnea on exertion and chest discomfort. On physical examination, there were diminished breath sounds on the left side. CT revealed what was thought to be a large left diaphragmatic hernia with the splenic flexure of the colon herniating into the left thorax. A loculated fluid collection with an air–fluid level was seen surrounding the left colon at the level of the mesh (Figure 4).

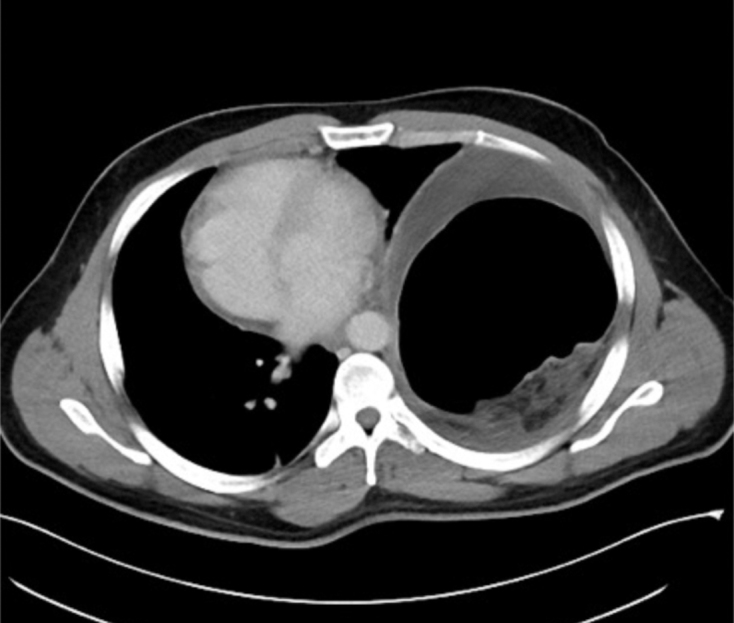

Figure 4.

Computed tomography showing a large left diaphragmatic hernia with mediastinal shift

Surgical repair options for this supposedly recurrent hernia were discussed. The patient was scheduled for laparoscopic exploration and mesh removal, with a left thoracotomy likely to be required.

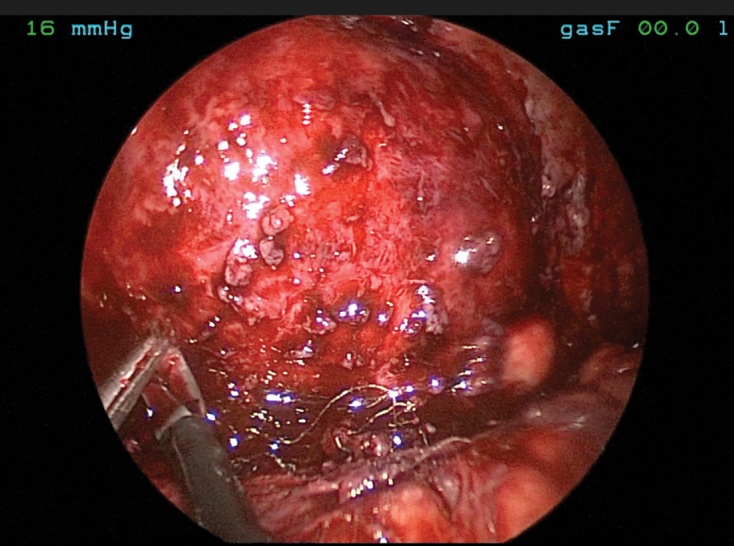

At laparoscopy, the transverse colon and omentum were found adherent to the left hemidiaphragm, and were carefully separated. Initial inspection revealed the polypropylene mesh (which was partially detached) and what appeared to be a large left diaphragmatic hernia defect measuring approximately 10cm. Over 100ml of turbid fluid corresponding to the collection seen on CT was drained. The mesh was then removed, along with all visible spiral tacks. Inspection above the presumed diaphragmatic defect showed diffuse granulation tissue but no visible lung. The diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia was reconsidered at this point as the diaphragm appeared intact (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Laparoscopic view demonstrating an intact diaphragm with granulation tissue and fibrinous inflammation

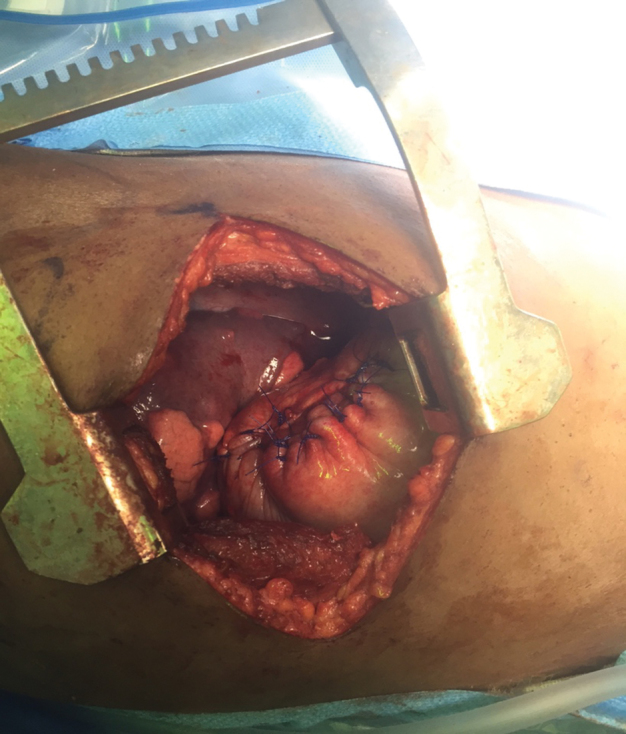

No further intervention was deemed possible from a laparoscopic or abdominal approach and the patient was repositioned for a left thoracotomy. A posterolateral thoracotomy in the seventh intercostal space was made. Further inspection revealed no diaphragmatic hernia, but instead a large diaphragmatic eventration. A full-thickness opening was made in the diaphragm to confirm the intra-abdominal contents below and to confirm that no further fluid remained. The defect was then closed primarily. A diaphragmatic plication was performed with size 0 polypropylene sutures (Figure 6). A chest tube was placed and the thoracotomy closed in multiple layers.

Figure 6.

Left lateral thoracotomy with plication of the diaphragm

Postoperative radiography demonstrated full lung expansion, no mediastinal shift and mild elevation of the left hemidiaphragm (Figure 6). The patient’s recovery was uneventful and he was discharged three days after surgery. His abdominal fluid culture grew Escherichia coli, sensitive to ciprofloxacin. He was seen one week and three weeks later, and had an excellent recovery.

Discussion

Congenital diaphragmatic eventration is a rare abnormality involving the muscular portion of the diaphragm. Most adult patients are asymptomatic and eventration is noted incidentally on imaging. Symptomatic patients typically present with dyspnea on exertion and orthopnea due to the elevated diaphragm and ventilation–perfusion mismatch as well as impaired ventilation.3 Non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms such as dyspepsia, epigastric pain, belching and nausea may also be present.1

The diagnosis of symptomatic eventration is primarily clinical and relies mostly on patient history and imaging. The presenting symptoms can be non-specific leading the diagnosis of diaphragmatic eventration to be mainly one of exclusion. There are few characteristic findings on physical examination, but suggestive findings may include Hoover’s sign (paradoxical inward movement of the lower costal margin during inspiration) or an abdominal paradox (the rib cage and abdomen move out of phase with each other). There are also common findings in diagnostic testing. For example, pulmonary function testing may reveal a restrictive pattern and chest x-ray may demonstrate an elevated hemidiaphragm. However, these are again non-specific findings with a wide range of differential diagnoses, and should be investigated further with CT and a fluoroscopic sniff test.1

Distinguishing congenital diaphragmatic eventration from a diaphragmatic hernia prior to surgery can be challenging. Imaging interpreted by experienced radiologists and surgeons can easily miss the diagnosis of diaphragmatic eventration. In our patient, the correct diagnosis was not apparent even at laparoscopy in the initial surgery. There are several case reports in the literature describing similar circumstances, where an eventration was not suspected and untimately diagnosed at surgery.4,5

The indication for surgical repair of diaphragmatic eventration is symptomatic relief. Unlike diaphragmatic hernias, no risk of incarceration or obstruction exists and asymptomatic eventration can be observed.

A diagnostic laparoscopy is an appropriate surgical approach for both diaphragmatic eventration and hernia, with successful repairs described for both. Furthermore, even though eventration is relatively uncommon, one must consider this among the differential diagnoses of diaphragmatic hernia prior to surgery (especially intraoperatively, when things are not clear cut). The diagnosis can be made during laparoscopy if performed by an experienced surgeon. Alternatively, when there is high suspicion for diaphragmatic eventration, a thoracoscopy can be carried out to confirm the diagnosis and prevent unnecessary abdominal dissection.

The preferred treatment for diaphragmatic eventration is plication of the diaphragm. A variety of plication techniques - either from a thoracic or abdominal approach-may be performed, such as thoracotomy, laparotomy, laparoscopy and video assisted thoracic surgery for plication can be administered, either from a thoracic or abdominal approach.6,7 Regardless of the technique used, diaphragmatic plication repositions and flattens the diaphragm to its normal position during inspiration while pushing back the abdominal organs to their usual location in the abdomen to allow lung expansion.

Conclusions

Diaphragmatic eventration is a rare condition that necessitates surgical treatment only in symptomatic patients. The diagnosis can be challenging and should be considered among the differential diagnoses of diaphragmatic hernia. The treatment of choice is diaphragmatic plication and this can be undertaken via an open or minimally invasive technique, according to the surgeon’s preference and experience.

References

- 1.Groth SS, Andrade RS. Diaphragmatic eventration. Thorac Surg Clin 2009; : 511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen P. Eventration of the diaphragm. Thorax 1959; : 311–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen C, Che G. Congenital eventration of hemidiaphragm in an adult. Ann Thorac Surg 2012; : e137–e139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Go P, Hammoud Z. Eventration of the diaphragm presenting as spontaneous pneumothorax. Cleve Clin J Med 2016; : 19–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deveer M, Beydilli H, Cullu N, Sivrioglu AK. Diaphragmatic eventration presenting with sudden dyspnoea. BMJ Case Rep 2013; bcr2013008613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yalcinkaya I, Evman S, Lacin T et al. Video-assisted minimally invasive diaphragmatic plication: feasibility of a recognized procedure through an uncharacteristic hybrid approach. Surg Endosc 2016. August 12 [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali Shah SZ, Khan SA, Bilal A et al. Eventration of diaphragm in adults: eleven years experience. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2014; : 459–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]