Abstract

This study investigated the photo-activated antibacterial function of a series of specifically prepared carbon dots with 2,2’-(ethylenedioxy)bis(ethylamine) as the surface functionalization molecule (EDA-CDots), whose fluorescence quantum yields (ΦF) ranged from 7.5% to 27%. The results revealed that the effectiveness of CDots’ photo-activated bactericidal function was correlated with their observed ΦF values. The antimicrobial activities of these EDA-CDots against both Gram negative and Gram positive model bacterial species (E. coli and Bacillus subtilis, respectively) were also evaluated under conditions of varying other experimental parameters including dot concentrations and treatment times. Optimization of the bactericidal effect of the EDA-CDots by a combination of the selected ΦF, concentration and treatment time was explored, and mechanistic implications of the results are discussed.

ToC Entry

The antibacterial performance of carbon dots is correlated with their photoexcited state properties for mechanistic elucidation.

Introduction

Infectious diseases caused by bacteria have been constant threats to public health. Photo-activated antimicrobial technology is a rapidly developing field in response to the demand in development of effective treatments, and the control and prevention of bacterial infectious diseases. Traditionally, this technology is based on the use of UV light to illuminate photo-sensitizers such as colloidal TiO2 to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), including singlet oxygen, superoxide and hydroxyl radicals to kill pathogenic bacteria (1). To reduce human exposure to the bio-hazardous UV light, agents that can be activated in the visible spectrum have recently been receiving increasing attention. A number of such agents have been developed, including various modifications to TiO2 nanoparticles (2), organic dyes with gold nanoparticles (3–5), and cationic fullerenes (6). More recently, carbon dots have been demonstrated for their great potential in serving as effective light-activated antimicrobial agents (7).

Carbon dots (CDots) are generally small carbon nanoparticles with various surface passivation schemes (8, 9), in which chemical functionalization with organic molecules has been most effective (9–11) Thus, carbon dots may be considered as a special kind of “core-shell” nano-dot structures, each with a carbon nanoparticle core and a thin shell of soft materials (organic or biological species for surface modification). The photoexcited state properties and redox processes in carbon dots resemble those found in conventional nanoscale semiconductors, such as the efficient photoinduced charge separation for the formation of radical anions and cations (electrons and holes) and their radiative recombinations to result in bright and colorful fluorescence emissions (9, 12, 13). It has been demonstrated that the photo-generated electrons and holes in carbon dots can drive various catalytic processes (14, 15). Carbon dots also exhibit strong photodynamic effect (10, 11), and the associated phototoxicity has been used to kill cancer cells (16). However, in the absence of light-activation, carbon dots are generally nontoxic to various cell lines (10, 11).

The same photoinduced redox processes have been credited for the photocatalytic activities that make carbon dots an excellent candidate as antibacterial agents (7, 17). In the recently reported study, it was confirmed that antimicrobial function of CDots could be activated under visible/natural light illumination (7). Mechanistically, however, the photoexcited states and redox processes in carbon dots are complex, dependent also on the dot structures (18, 19). More specifically, it is known that the fluorescence quantum yields of CDots are affected significantly by the surface passivation of the core carbon nanoparticles, with a more effective passivation corresponding to higher fluorescence quantum yields (9–11, 20). In photophysics, fluorescence quantum yields reflect the photoexcited state properties and processes, which in CDots also dictate the observed phototoxicity against cancer cells and bacteria. Thus, an examination on the correlation of antimicrobial activities of CDots with their fluorescence quantum yields and by extension their structural parameters such as surface passivation should be valuable in the development of these new antimicrobial agents, aiding also the desire mechanistic elucidation.

In this study, we synthesized samples of carbon dots with 2,2’-(ethylenedioxy)bis(ethylamine) as the surface functionalization molecule (EDA-CDots), whose fluorescence quantum yields (ΦF) were different, and we examined the bactericidal function (in terms of viable cell reduction) of these EDA-CDots samples in correlation with their observed ΦF values. The antimicrobial activities of the EDA-CDots samples against both Gram negative and Gram positive model bacterial species (E. coli and Bacillus subtilis, respectively) were also evaluated under conditions of varying other experimental parameters including dot concentrations and treatment times. An optimization of the bactericidal effect of the EDA-CDots by a combination of the selected ΦF, concentration and treatment time was explored, and mechanistic implications of the results are discussed.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis and characterization of EDA-CDots

The commercially acquired carbon nanopowder sample (Sigma-Aldrich) was refluxed in aqueous nitric acid (2.6 M) for 24 h, washed with deionized water repeatedly, and then dried under nitrogen. The treated sample (200 mg) was further treated in the mixed acid of concentrated sulfuric acid and nitric acid (3/1 v/v, 10 mL) at 60 °C with sonication for 1 h and then refluxing for 2 h. To the resulting mixture was added deionized water (100 mL) for centrifugation at 20,000 g for 30 min to keep the supernatant. It was dialyzed in a membrane tubing (cutoff molecular weight ∼ 500) against fresh water for 3 days to yield a stable dispersion of carbon nanoparticles.

For the synthesis of EDA-CDots, the carbon nanoparticles in aqueous dispersion were recovered by the removal of water via evaporation, and then refluxed in neat thionyl chloride for 12 h. Upon the removal of excess thionyl chloride, the treated sample (50 mg) was mixed well with carefully dried EDA (Sigma-Aldrich) liquid in a round-bottom flask, heated to 120 °C, and vigorously stirred under nitrogen protection for 3 days. The reaction mixture back at room temperature was dispersed in water and then centrifuged at 20,000 g to retain the supernatant. It was dialyzed in a membrane tubing (cutoff molecular weight ∼ 500) against fresh water to remove unreacted EDA and other small molecular species to obtain an aqueous solution of the as-synthesized EDA-CDots. The as-synthesized sample containing EDA-CDots of different fluorescence quantum yields was fractionated on a Sephadex™ G-100 gel column (packed in house with commercially supplied gel sample) with water as eluent. For the determination of fluorescence quantum yields, the established relative method was applied, namely by using a known fluorescence standard such that the absorbances of the sample and standard are matched at the excitation wavelength and their corresponding fluorescence intensity integrations are compared. Three fractions of 7.5%, 17%, and 27% in observed fluorescence quantum yields (400 nm excitation, in reference to 9,10-bis(phenylethynyl)-anthracene as fluorescence standard) were obtained, and they were characterized by using spectroscopy and microscopy techniques, as reported previously (21, 22).

Bacterial culture

Escherichia coliK12 (Gram negative) and Bacillus Subtilis (Gram positive) cultures were grown in 10 mL nutrient broth (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) by inoculating the broth with a single colony of a plated culture on a Luria–Bertani (LB) agar plate, and incubated overnight at 37 °C, respectively. Freshly grown E. coli or B. Subtilis cells were washed three times with PBS and then re-suspended in PBS for further experimental uses.

Surface plating method to determine viable cell number

The actual cell concentration in the suspension was determined by the traditional surface plating method. Briefly, the bacterial suspensions were serially diluted (1:10) with PBS. Aliquots of 100 µL appropriate dilutions were surface-plated on LB agar plates (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). After incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, the number of colonies on the plates were counted, and the viable cell numbers were calculated in colony forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) for all the treated samples and the controls.

Treatment of bacterial cells with CDots

Treatment of bacterial cells with CDots was performed in 96-well plates. Each well was added with 150 µL bacteria cell suspension and 50 µL CDots of various concentrations. The final bacterial cell concentration in each well was about ∼105 – 106 CFU/mL for B. subtilis or 106 −107 CFU/mL for E. coli, and the concentration of CDots was varied as needed (triplicates for each concentration). The plates were either exposed to visible light from a 12 V 36 W LED light at a distance of 10 cm away from the top surface of the plate (notated as lab light in figures), or room light from 50 W LED light mounted on the 9-feet ceiling in the laboratory (notated as room light in figures), or kept in dark by wrapping with foil (notated as dark in figures) for desired period of time.

After the treatment, the viable cell numbers in the control and treated samples were determined by the traditional plating method using the same procedure as described above. The reduction in viable cell number in the CDots treated samples in comparison to the controls was used to evaluate the efficiency of bactericidal function of the CDots.

Fluorescence microscopic imaging

In order to visualize whether bacterial cells formed aggregates upon the treatment with carbon dots, and to visualize the live and dead cells in treated samples, the control bacterial samples and the carbon dots-treated samples were stained with Live/Dead Baclight™ bacterial viability kit (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR). The kit employs two nucleic acid dyes—the green SYTO 9 and the red propidium iodide dye. The propidium iodide dye penetrates only bacteria with damaged membranes. The kit stains live cells with intact membranes in green, and dead cells with damaged membranes in red. The fluorescent images were taken on a Nikon ECLIPSE E600FN fluorescence microscope (Japan) with a Coolsnap HQ camera (Roper Scientific, Inc.—Photometric, Tucson, AZ) using a FITC (Fluorescin isothiocyanate) filter.

Results and Discussion

Optical property of the as-synthesized EDA-CDots

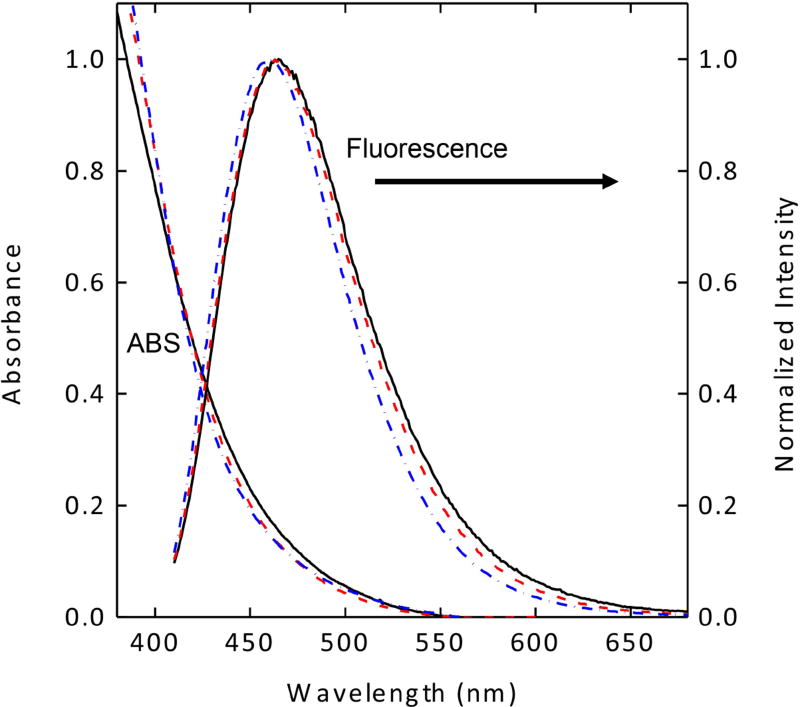

The carbon nanoparticles harvested from commercially supplied carbon nanopowder sample in established procedures were functionalized with EDA under amidation reaction conditions to obtain EDA-CDots, as reported previously (21, 22). According to results from atomic force microscopy (AFM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) characterizations, the EDA-CDots were on the order of 5 nm in diameter (21). Previous studies also suggested that the optical properties of carbon dots, fluorescence brightness or quantum yields in particular, are dependent on the effectiveness of carbon nanoparticle surface passivation via the chemical functionalization with organic molecules such as EDA (22). Since the as-synthesized sample of carbon dots is generally a mixture of dots with somewhat different levels of carbon nanoparticle surface functionalization, they can be separated into various fractions on an aqueous gel column (22). In this study, the as-synthesized sample of EDA-CDots was separated into three fractions. These fractions are very stable aqueous solutions, without any precipitation. As shown in Figure 1, the absorption and fluorescence spectra of the different fractions are similar, consistent with what have generally been observed in the fractionation of carbon dots (22, 23). However, the observed fluorescence quantum yields (ΦF) were significantly different, 7.5%, 17%, and 27% for the three fractions at 400 nm excitation, again consistent with what have found generally in other studies concerning the fractionation of carbon dots (22). Fluorescence decays of these samples in aqueous solution are all multi-exponential, for which the estimated average lifetimes are on the order of 5–6 ns.

Figure 1.

Absorption (ABS) and fluorescence spectra of the three fractionated samples of EDA-CDots with different fluorescence quantum yields (7.5%: solid line; 17%: dash line; 27%: dash-dot line).

Bactericidal function of EDA-CDots: Gram positive vs. Gram negative bacteria

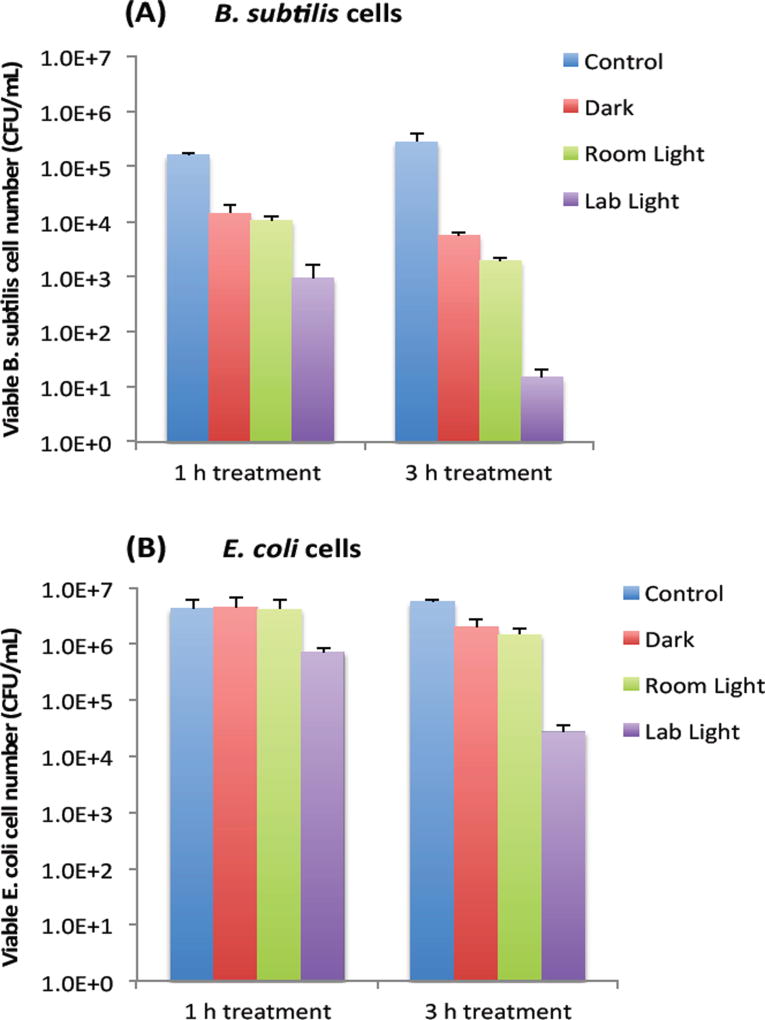

Bactericidal functions of EDA-CDots to Gram positive B. subtilis cells and Gram negative E. coli cells were evaluated under different light conditions by the viable cell reduction determined by the surface plating method. Fig. 2A and 2B show the viable cell reduction of B. subtilis cells and E. coli cells upon treatments with EDA-CDots (ΦF 27%) at 15.8 µg/mL for 1 h and 3 h in dark, under room light and lab light, along with the untreated control samples. As shown in Fig. 2A, to B. subtilis cells, 1 h treatment with EDA-CDots in dark and room light resulted in a similar magnitude of viable cell reduction, at approximately 1 log (∼90%), while under lab light, the same treatment resulted in approximately 2 log (∼99%) viable cell reduction. When the treatment time was increased to 3 h, the bactericidal effects in dark and under room light did not increase significantly, but the bacterial killing effect of EDA-CDots treatment under lab light increased dramatically to approximately 4 logs (∼99.99).

Figure 2.

The viable cell reduction of B. subtilis cells and E. coli cells. (A) B. subtilis cells and (B) E. coli cells upon treatments with EDA-CDots (ΦF 27%) at 15.8 µg/mL for 1 h and 3 h under different light conditions.

We further examined the bactericidal function of EDA-CDots at same concentration and same light conditions to Gram negative bacterial E. coli cells. Although the relative viable cell number reduction of E. coli cells between different light conditions (dark vs. room light vs. lab light) presented a similar overall pattern as that of Gram positive B. subtilis cells, for both 1 h and 3 h treatments, there were almost no viable cell reduction in dark and under room light conditions. The magnitudes in viable cell reduction of E. coli cells under lab light treatment were ∼1 log at 1 h treatment and ∼2 logs at 3 h treatment, which were significantly lower than those observed for B. subtilis cells under the same treatment conditions. For both types of cells, when treated with EDA-CDots at other given concentrations, the magnitude of viable cell reduction showed the similar pattern in that CDots with lab light treatment always showed the best effectiveness in viable cell reduction in comparison to CDots treatment under room light and in dark.

The results here not only confirmed again the light-activation bactericidal function of EDA-CDots to both Gram positive and Gram negative bacterial cells, but also indicated such bactericidal function was affected by the light condition and the light illumination time, which implies that photoexcitation associated properties of EDA-CDots could be a significant factor that contributes to its light-activated bactericidal activity.

It is also noted that EDA-CDots did exhibited better effectiveness in its light-activated bactericidal function to Gram positive bacterial cells than to Gram negative bacterial cells. This is mostly likely due to the distinct difference in cell wall structures between Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria. The Gram positive cell wall contains a very thick peptidoglycan layer. Unlike the Gram positive cell wall, the Gram negative cell wall contains a thin peptidoglycan layer adjacent to the cytoplasmic membrane, and in addition to the peptidoglycan layer, the Gram negative cell wall also contains an additional outer membrane composed of phospholipids and lipopolysaccharides which are exposed to the external environment. It is not surprising to observe the different bactericidal functions of the EDA-CDots against the two types of bacterial cells, as it was shown in previous studies that carboxyfullerene affected Gram positive bacteria effectively (at 50 µg/mL) but had no effect on Gram negative bacteria at concentrations up to 500 µg/mL (24). Even antibiotics have exhibited different effect on Gram positive and Gram negative bacterial cells due to the difference in cell wall and cell membrane between the two bacterial types. For example, lipopeptide daptomycin is effective against Gram positive bacteria but not effective on Gram negative bacterial cells. The resistance of some Gram negative bacteria to many antimicrobial agents is often due to the inability of these agents to cross the outer membrane. This is likely also true for the observed lower efficacy of the EDA-CDots to E. coli cells than to B. subtilis cells under the same treatment conditions.

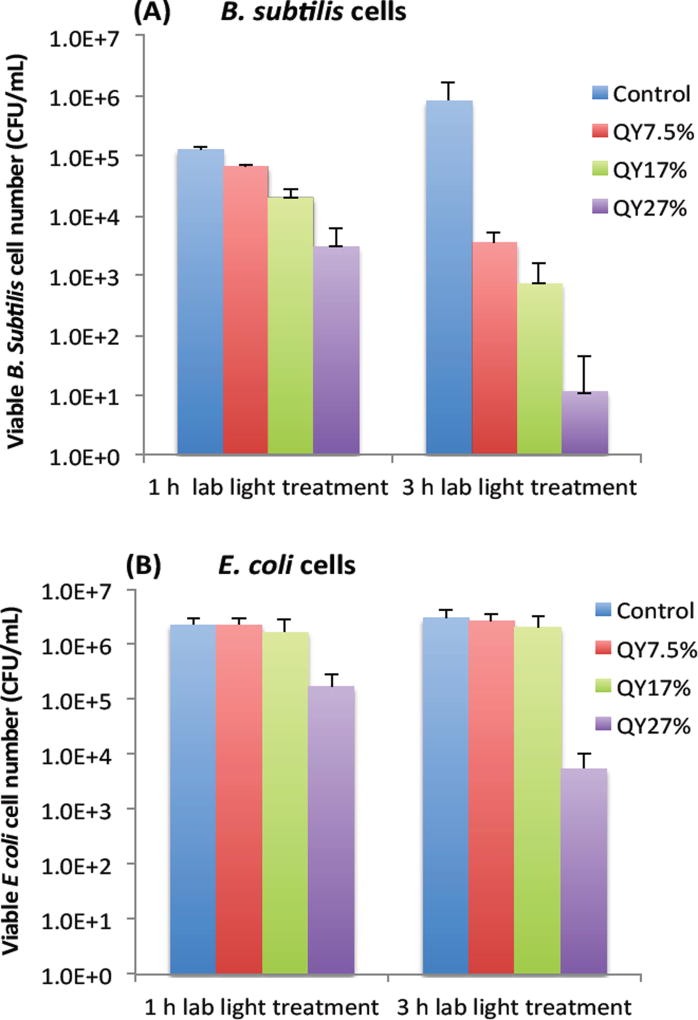

EDA-CDots’ bactericidal function: correlation with fluorescence quantum yields

To further look into whether the photoexcitation associated properties of EDA-CDots is a important factor that contributes to its light-activated bactericidal activity, we examined the bactericidal effect of EDA-CDots of three different ΦF under the same treatment conditions. Fig. 3A and 3B show the viable cell reduction of B. subtilis cells (A) and E. coli cells (B) after the cells were treated with EDA-CDots of fluorescence quantum yields (ΦF) of 7.5%, 17%, and 27%, at the same concentration of 15.8 µg/mL for 1 h and 3 h under lab light illumination. Fig. 3A shows a clear trend of increasing viable cell reduction of B. subtilis cells post-treatment of the CDots with higher ΦF values at same treatment conditions (the same CDots concentration and treatment time). At 1 h treatment time, the log reductions in viable cell number for B. subtilis cells upon treatment with CDots of ΦF 7.5%, 17%, and 27% were 0.3, 0.8, and 1.6 log, respectively. At 3 h treatment, the viable cell reductions upon the treatment of these CDots at the same concentration increased significantly, with ∼2.4, 3.1, 4.9 logs for the EDA-CDots with ΦF 7.5%, 17%, and 27%, respectively. In both cases, the CDots with ΦF 27% exhibited the most efficient bactericidal effect to B. subtilis cells, followed by CDots with ΦF 17%, and then CDots with ΦF 7.5%. In Fig. 3B, to E. coli cells, only the CDots with highest ΦF (27%) exhibited bactericidal effect, with ∼1.1 and ∼2.7 log reduction at 1 h and 3 h treatment time, respectively, while the EDA-CDots with lower ΦF values did not exhibit any meaningful bactericidal effect under the given treatment conditions (15.8 µg/mL for 1 and 3 h). Based on the comparison between results in Fig. 3A and 3B, the bactericidal activity of each of the EDA-CDots samples with different ΦF values was much more effective towards Gram positive B. subtilis cells than to Gram negative E. coli cells. Nevertheless, the overall results demonstrated clearly that the bactericidal function of the EDA-CDots was obviously correlated with their ΦF values, with the sample of a higher ΦF being more effective. Additionally, similar to many other antimicrobial agents, the EDA-CDots’ bactericidal effect varied with the treatment time, and also with bacterial species.

Figure 3.

The viable cell reduction of B. subtilis cells and E. coli cells. (A) B. subtilis and (B) E. coli cells upon the treatments with EDA-CDots samples of ΦF 7.5%, 17%, and 27% at 15.8 µg/mL under lab light treatment for 1 h and 3 h.

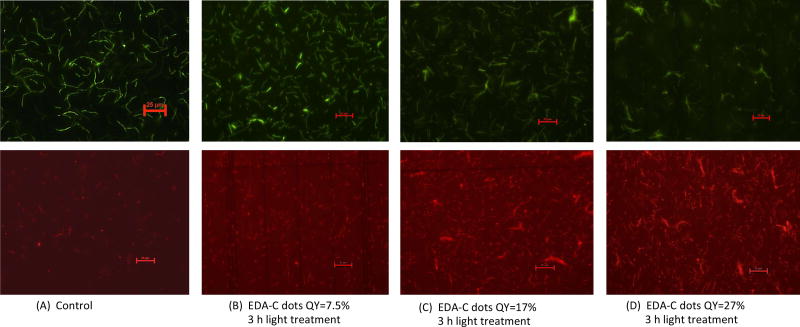

Fluorescence imaging of EDA-CDots treated cells

We further examined more directly the cells post-treatment with EDA-CDots under fluorescent microscope. After the treatment with EDA-CDots of different ΦF values, the cells were stained with the LIVE/DEAD Baclight™ bacterial viability kit in order to visualize live and dead cells. Fig. 4 shows the representative images of B. subtilis cells after they were treated with 15.8 µg/mL EDA-CDots of ΦF 7.5%, 17%, and 27% for 3 h, along with the control samples without CDots treatment. Each pair of green (upper panel) and red (lower panel) images provided the status of cells at the same spot using the same exposure time taken with FITC and TRITC filters. Fig. 4A indicated that in control sample, there were high density of live cells (green) with a few dead cell (red). From Fig. 4B to 4D, the density of live cells (green) reduced while the density of dead cells (red) increased, which indicated the more significant bactericidal effect of EDA-CDots with a higher ΦF. The visualization of increased population of dead cells with treatment of CDots with higher ΦF in these images agreed with the trend in the viable cell reduction experiments. The images also indicated that the cells were not severely aggregated when they were treated with EDA-CDots.

Figure 4.

Representative fluorescent images of B. subtilis cells. Cells were stained with BacLight bacterial live/dead kit after the cells were treated with EDA-CDots samples of different ΦF values at 15.8 µg/mL for 3 h, along with the control. Each pair of the green and red images were taken at the same spot with same exposure time using FITC and TRITC filters. Scale bar = 25 µm.

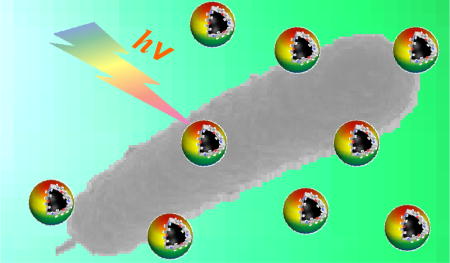

These images also showed that the bacterial cells were still intact after the CDots treatment, although the dead cells most likely had some extent of membrane damage as they were stained in red by penetration of the propidium iodide dye through damaged membranes. This observation is not surprising as CDots have been demonstrated no cytotoxicity when used in mammalian cellular imaging, causing no change in cellular morphology (25, 26). Additionally, CDots have been used as drug delivery and gene carrier agents where they penetrated a number of organelles without inducing any adverse effect (17, 27, 28). It is believed that CDots’ bactericidal activity is more a result of its photodynamic effect, which most likely similar to other photosensitizers, tend to cause ultrastructural alterations to bacterial cells including chromosomal array modification, irregularities in cell wall or membrane (29), and ultimately lead to cell death.

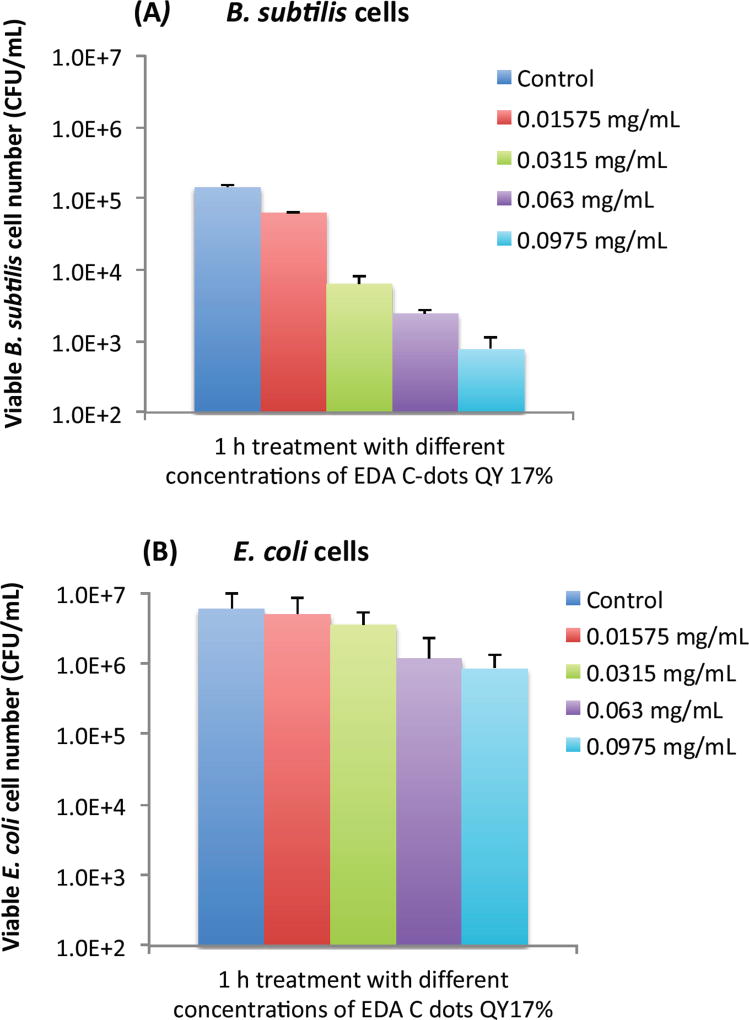

EDA-CDots’ bactericidal function: concentration dependence

Not surprisingly, the bactericidal effect of EDA-CDots was also found to be concentration dependent. Using the EDA-CDots with ΦF 17% as an example, Fig. 5A and 5B show the viable cell reductions of B. subtilis (A) and E. coli cells (B) after the cells were treated with different concentrations of the EDA-CDots of ΦF 17%. As shown in Figure 5A, treatments with EDA-CDots at 15.8, 31.5, 63, and 97.5 µg/mL for 1 h resulted in approximately 0.36, 1.36, 1.77 and 2.27 logs reductions in viable cell numbers of B. subtilis. A similar increasing trend in viable cell number reduction in treatments with increasing concentration of EDA-CDots was observed in E. coli cells, though the magnitudes in log reduction were obviously lower than those in B. subtilis cells at each corresponding CDots concentration.

Figure 5.

The viable cell reductions of B. Subtilis cells and E. coli. (A) B. Subtilis cells and (B) E. coli after the cells were treated with EDA-CDots of ΦF17% at concentrations ranging from 15.8 µg/mL to 97.5 µg/mL under lab light illumination for 1 h.

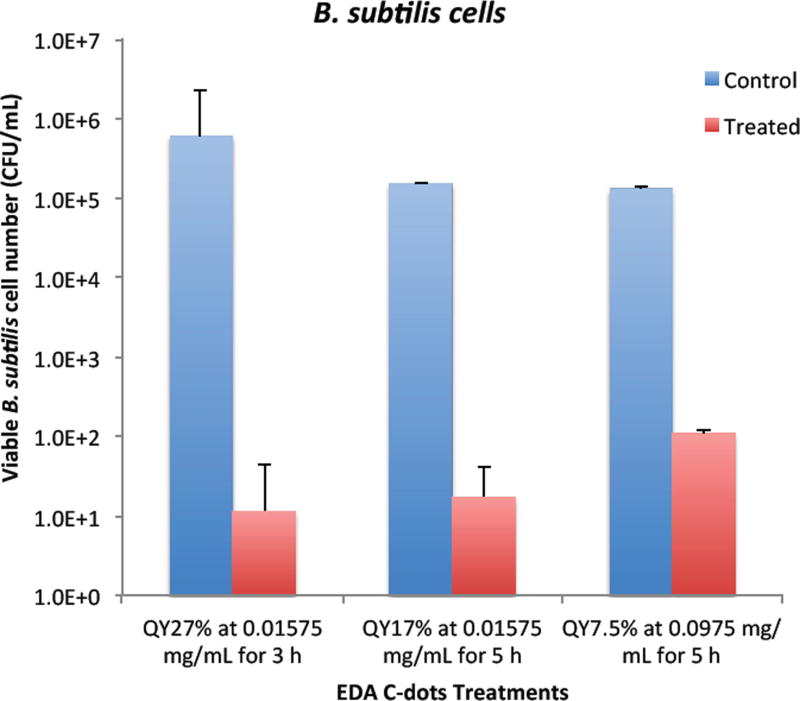

Tuning bactericidal activity of CDots by a combination of ΦF, concentration, and treatment time

As demonstrated above, the bactericidal effect of EDA-CDots was obviously tunable with samples of different ΦF values, and also with different dot concentrations and treatment times. We further explored for an optimal combination of these factors to achieve more effective bacterial killing. Fig. 6 shows the results of viable cell reductions in B. subtilis cells by some of the treatments combining the selected CDots’ ΦF, concentration and treatment time to achieve 3–5 logs reduction in viable cell number. As also shown in Fig. 6, the treatment with EDA-CDots of ΦF 27% at 15.8 µg/mL for 3 h under lab light could achieve approximately 4.7 logs reduction in viable B. subtilis cells; the treatment with EDA-CDots of a lower ΦF of 17% at the same concentration (15.8 µg/mL) with a longer treatment time of 5 h could also achieve ∼3.9 logs reduction in viable cell number; 5 h treatment with the CDots of the lowest ΦF (7.5%) at a higher concentration of 97.5 µg/mL could also achieve a reasonably good viable cell reduction outcome (∼3.1 logs) in B. subtislis cells. Overall, the magnitudes of viable cell reduction achieved by EDA-CDots treatments are similar to or better than those by a variety of reported physical and chemical methods and other antimicrobial nanomaterials for inactivation of bacteria (30, 31). For example, Shin et al. reported that an antimicrobial ice which contained 100 ppm ClO2 for reducing pathogen load on fish skin achieved the total reduction of E. coli O157:H7, S. typhimurium and L. monocytogenes by 4.8, 2.6 and 3.3 log, respectively, for a 120 min treatment (31). MacGregor et al. reported a method using a pulsed power light source (380 kW/cm2 in the power density) to inactivate food-related pathogenic bacteria and achieved 2 and 3 log reductions of E. coli O157:H7 and Listeria (30). For another carbon-based nanomaterial, single walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), as antimicrobial material, results from our studies (32, 33) and by others (34, 35) suggested <1 log to ∼4 — 6 log viable cell reduction of E. coli cells and other cells with the use of SWCNTs from different sources. Overall, the results obtained in this study show the great potential of carbon dots as light-activated antimicrobial agents. The tuning of the dot properties such as ΦF and treatment parameters including concentration and treatment time may allow the optimization to achieve the maximal antimicrobial effect of carbon dots.

Figure 6.

Adjustable bactericidal effect of EDA-CDots by a combination of CDots’ ΦF, concentration, and treatment time to achieve ∼3–5 log reduction in viable cell number of B. subtilis cells.

Mechanistic Implications

Mechanistically, the fluorescence emissions in CDots are attributed to radiative recombinations of photo-generated electrons and holes trapped at diverse surface defect sites(12, 13). As reported recently (19, 23), the observed fluorescence properties including quantum yields and decays may be explained in terms of two sequential processes following photoexcitation, the first for the formation of the emissive excited states, which competes with other deactivation pathways of the initially generated electrons and holes with a quantum yield of Φ1, and then the other from the emissive states for fluorescence (with a quantum yield of Φ2) and competing nonradiative decay pathways. Thus, the observed fluorescence quantum yields (ΦF) reflect a combination of the two processes, ΦF = Φ1Φ2. Available experimental results suggested that the effect of more effective surface passivation via the functionalization of organic molecules for higher observed fluorescence quantum yields is primarily through the Φ1 process (9, 22, 27). For the light-activated bactericidal functions of EDA-CDots, their obvious correlation with observed ΦF values of the dot samples discussed above implies that the Φ1 process following the photoexcitation contributes significantly to the bactericidal activities. Among possible reactive species responsible for the bacteria-killing activities could be the initially formed redox pairs at the surface defect sites, which are stabilized by the improved surface passivation in dot samples of higher ΦF values, and/or their generated secondary species such as singlet oxygen and/or hydroxyl radicals. However, the correlation discussed above does not exclude contributions of the emissive excited states to the observed bactericidal activities, just their probably being similar among the different dot samples. These excited states should resemble those found in many organic dyes, such as porphyrins and phthalocyanines, with their associated photodynamic effect likely being responsible for bactericidal activities (36).

Conclusions

The results from this study clearly revealed that the photo-activated antibacterial function of EDA-CDots was correlated with its fluorescence quantum yields (ΦF). The CDots with higher observed ΦF values exhibited higher effectiveness in their light-activated bactericidal function compared to those with a lower ΦF under the same treatment conditions, and this was true for both Gram negative and Gram positive model bacterial species. The results suggest that the process and/or species associated with the formation of the emissive excited states in the CDots contribute significantly to the bactericidal activities. Additionally, other experimental parameters including dot concentration and treatment time were also factors affecting the effectiveness of CDots’ photo-activated antibacterial function. Collectively, optimization of the bactericidal effect of the CDots can be achieved by a combination of the selected ΦF, concentration and treatment time. Mechanistic implications of the results were explored, and needs and opportunities for further investigations were identified.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by NIH Grant R15GM114752 (to L.Y., Y.-P.S. and Y.T.)

References

- 1.Hamblin MRMP. Advances in Photodynamic Therapy : Basic, Translational and Clinical. Norwood, MA: Artech House; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng CL, Sun DS, Chu WC, Tseng YH, Ho HC, Wang JB, et al. The effects of the bacterial interaction with visible-light responsive titania photocatalyst on the bactericidal performance. J Biomed Sci. 2009 Jan 15;16:7. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perni S, Piccirillo C, Pratten J, Prokopovich P, Chrzanowski W, Parkin IP, et al. The antimicrobial properties of light-activated polymers containing methylene blue and gold nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2009 Jan;30(1):89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naik AJT, Ismail S, Kay C, Wilson M, Parkin IP. Antimicrobial activity of polyurethane embedded with methylene blue, toluidene blue and gold nanoparticles against Staphylococcus aureus; illuminated with white light. Mater Chem Phys. 2011 Sep 15;129(1–2):446–50. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noimark S, Allan E, Parkin IP. Light-activated antimicrobial surfaces with enhanced efficacy induced by a dark-activated mechanism. Chem Sci. 2014;5(6):2216–23. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang LY, Terakawa M, Zhiyentayev T, Huang YY, Sawayama Y, Jahnke A, et al. Innovative cationic fullerenes as broad-spectrum light-activated antimicrobials. Nanomed-Nanotechnol. 2010 Jun;6(3):442–52. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meziani MJ, Dong X, Zhu L, Jones LP, LeCroy GE, Yang F, et al. Visible-Light-Activated Bactericidal Functions of Carbon “Quantum” Dots. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016 May 4;8(17):10761–6. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b01765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun YP, Zhou B, Lin Y, Wang W, Fernando KA, Pathak P, et al. Quantum-sized carbon dots for bright and colorful photoluminescence. J Am Chem Soc. 2006 Jun 21;128(24):7756–7. doi: 10.1021/ja062677d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeCroy GE, Yang ST, Yang F, Liu YM, Fernando KAS, Bunker CE, et al. Functionalized carbon nanoparticles: Syntheses and applications in optical bioimaging and energy conversion. Coordin Chem Rev. 2016 Aug 1;320:66–81. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo PGS, Yang S, Sonkar S-T, Wang SK, Wang J, LeCroy H, Cao GE, Sun L, Carbon Y-P. “Quantum” Dots for Optical Bioimaging. J Mater Chem B. 2013;1:2116–27. doi: 10.1039/c3tb00018d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo PJG, Yang F, Yang ST, Sonkar SK, Yang LJ, Broglie JJ, et al. Carbon-based quantum dots for fluorescence imaging of cells and tissues. Rsc Adv. 2014;4(21):10791–807. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao L, Meziani MJ, Sahu S, Sun YP. Photoluminescence properties of graphene versus other carbon nanomaterials. Acc Chem Res. 2013 Jan 15;46(1):171–80. doi: 10.1021/ar300128j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernando KA, Sahu S, Liu Y, Lewis WK, Guliants EA, Jafariyan A, et al. Carbon quantum dots and applications in photocatalytic energy conversion. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015 Apr 29;7(16):8363–76. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b00448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao L, Sahu S, Anilkumar P, Bunker CE, Xu JA, Fernando KAS, et al. Carbon Nanoparticles as Visible-Light Photocatalysts for Efficient CO2 Conversion and Beyond. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011 Apr 6;133(13):4754–7. doi: 10.1021/ja200804h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernando KAS, Sahu S, Liu YM, Lewis WK, Guliants EA, Jafariyan A, et al. Carbon Quantum Dots and Applications in Photocatalytic Energy Conversion. Acs Appl Mater Inter. 2015 Apr 29;7(16):8363–76. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b00448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juzenas P, Kleinauskas A, Luo PG, Sun YP. Photoactivatable carbon nanodots for cancer therapy. Appl Phys Lett. 2013 Aug 5;103(6) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim SY, Shen W, Gao Z. Carbon quantum dots and their applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2015 Jan 7;44(1):362–81. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00269e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao L, Meziani MJ, Sahu S, Sun YP. Photoluminescence Properties of Graphene versus Other Carbon Nanomaterials. Accounts Chem Res. 2013 Jan 15;46(1):171–80. doi: 10.1021/ar300128j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang F, LeCroy GE, Wang P, Liang W, Chen J, Fernando KAS, et al. Functionalization of Carbon Nanoparticles and Defunctionalization—Toward Structural and Mechanistic Elucidation of Carbon “Quantum” Dots. the Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2016;120(44):25604–11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Cao L, Yang ST, Lu F, Meziani MJ, Tian L, et al. Bandgap-like strong fluorescence in functionalized carbon nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010 Jul 19;49(31):5310–4. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LeCroy GE, Sonkar SK, Yang F, Veca LM, Wang P, Tackett KN, 2nd, et al. Toward structurally defined carbon dots as ultracompact fluorescent probes. ACS nano. 2014 May 27;8(5):4522–9. doi: 10.1021/nn406628s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu YM, Wang P, Fernando KAS, LeCroy GE, Maimaiti H, Harruff-Miller BA, et al. Enhanced fluorescence properties of carbon dots in polymer films. J Mater Chem C. 2016 Aug 7;4(29):6967–74. doi: 10.1039/C6TC01932C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu Y, Awak MMA, Yang F, Yan S, Xiong Q, Wang P, et al. Photoexcited state properties of carbon dots from thermally induced functionalization of carbon nanoparticles. J Mater Chem C. 2016;4:10554–61. doi: 10.1039/C6TC03666J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsao NL, T Y, Chou CK, Wu JJ, Liu CC, Lei HYJ. Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49:641–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/49.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding H, Cheng LW, Ma YY, Kong JL, Xiong HM. Luminescent carbon quantum dots and their application in cell imaging. New J Chem. 2013;37(8):2515–20. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Ma YQ, Li N, Zhu JL, Zhang T, Zhang W, et al. Preparation of Graphene Quantum Dots and Their Application in Cell Imaging. J Nanomater. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu LM, Sun Y, Li SL, Wang XL, Hu KL, Wang LR, et al. Multifunctional carbon dots with high quantum yield for imaging and gene delivery. Carbon. 2014 Feb;67:508–13. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang YF, Hu AG. Carbon quantum dots: synthesis properties and applications. J Mater Chem C. 2014;2(34):6921–39. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nitzan Y, Gutterman M, Malik Z, Ehrenberg B. INACTIVATION OF GRAM-NEGATIVE BACTERIA BY PHOTOSENSITIZED PORPHYRINS. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 1992;55(1):89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1992.tb04213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacGregor SJ, Rowan NJ, McLlvaney L, Anderson JG, Fouracre RA, Farish O. Light inactivation of food-related pathogenic bacteria using a pulsed power source. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1998 Aug;27(2):67–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1998.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin JH, Chang S, Kang DH. Application of antimicrobial ice for reduction of foodborne pathogens (Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhimurium Listeria monocytogenes) on the surface of fish. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97(5):916–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arias LR, Yang L. Inactivation of bacterial pathogens by carbon nanotubes in suspensions. Langmuir. 2009 Mar 3;25(5):3003–12. doi: 10.1021/la802769m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang C, Mamouni J, Tang Y, Yang L. Antimicrobial activity of single-walled carbon nanotubes: length effect. Langmuir. 2010 Oct 19;26(20):16013–9. doi: 10.1021/la103110g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang S, Pinault M, Pfefferle LD, Elimelech M. Single-walled carbon nanotubes exhibit strong antimicrobial activity. Langmuir. 2007 Aug 14;23(17):8670–3. doi: 10.1021/la701067r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang S, Herzberg M, Rodrigues DF, Elimelech M. Antibacterial effects of carbon nanotubes: size does matter. Langmuir. 2008 Jun 1;24(13):6409–13. doi: 10.1021/la800951v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prasanth CS, Karunakaran SC, Paul AK, Kussovski V, Mantareva V, Ramaiah D, et al. Antimicrobial photodynamic efficiency of novel cationic porphyrins towards periodontal Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria. Photochem Photobiol. 2014 May-Jun;90(3):628–40. doi: 10.1111/php.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]