Abstract

Diffuse neurofibroma is a rarely encountered subtype of neurofibroma but the most common to be misdiagnosed. Its imaging appearance is very similar to that of a vascular malformation, and it is often labelled one until a biopsy proves it to be otherwise. The infrequency of its association with neurofibromatosis makes it a rare and difficult diagnosis. Here, we report the case of a 16-year-old girl who presented with the complaint of a gradually progressive swelling around the right ankle and heel, which was initially diagnosed as a case of a vascular malformation. However, it subsequently turned out to be a diffuse neurofibroma.

Keywords: Diffuse neurofibroma, Haemangioma, Ultrasound

Sommario

Il neurofibroma diffuso è una rara variante di neurofibroma, ma anche quella più facilmente non riconosciuta. L’aspetto all’imaging può simulare quello di una malformazione vascolare e spesso viene così etichettato finchè una biopsia non dimostri essere altro. E’ la difficoltà ad associare tale aspetto con l’imaging che rende il neurofibroma raro e di difficile diagnosi. Viene qui riferito il caso di una ragazza di 16 anni che si è presentata lamentando una tumefazione gradualmente progressiva attorno alla caviglia e al tallone destri inizialmente diagnosticata come una malformazione vascolare, ma successivamente correttamente identificata come un neurofibroma diffuso.

Introduction

Neurofibromas are soft tissue tumours that affect young adults between the ages of 20 and 30 years [1]. They account for almost 5% of all soft tissue tumours and are generally benign [1, 2]. Histopathologically, they are divided into three types: local, plexiform, and diffuse. Of these, the diffuse variety is the least common, but it is the one most often confused with a vascular malformation owing to its close imaging appearance [1–3, 5]. Diffuse neurofibromas affect the skin, and the subcutaneous tissues in particular, of the head and neck region, trunk, and extremities [4].

Case report

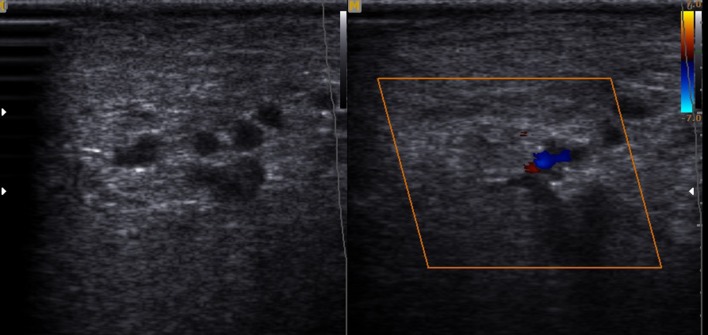

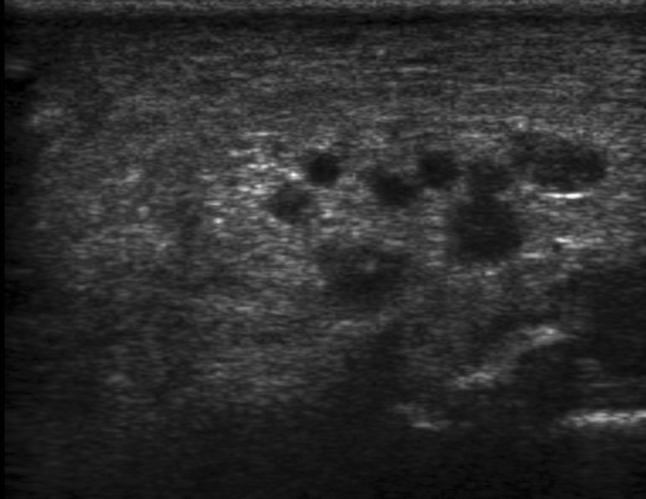

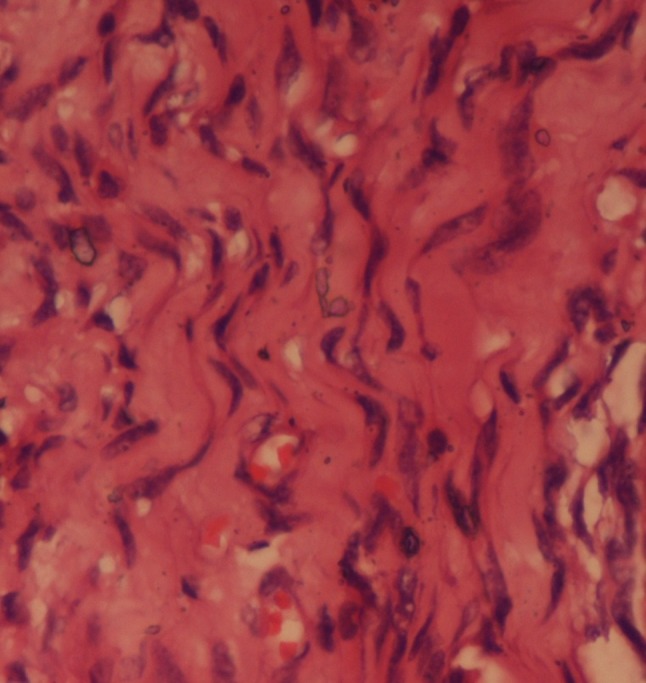

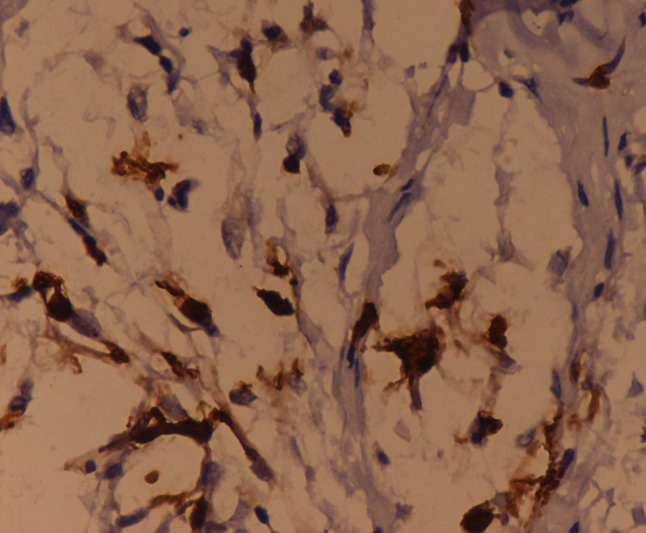

Herein, we report the case of a 16-year-old female who presented to the orthopaedics clinic with the complaint of a painless soft tissue swelling involving the right ankle and foot. She first noted the swelling at about 8 years of age. Initially, it was small, but later, the lesion gradually painlessly progressed to the present size. It completely surrounded the ankle and the heel region. The involved region experienced overgrowth compared to that on the opposite side. The skin over the swelling was normal with no evidence of any discolouration. On palpation, the temperature of the lesion was not raised. The lesion was soft to touch, but it was not possible to distinguish the margins from the adjacent normal area, suggesting an ill-defined lesion. In consistency with the examination findings, the provisional diagnosis of a vascular malformation was considered. The patient was subjected to ultrasonography. It showed an increase in the thickness of the soft tissue, which appeared hyperechoic, comparable to the adjacent normal fat density with multiple interspersed hypoechoic areas within it (Fig. 1). On colour Doppler evaluation, these hypoechoic areas showed slow flow, which it was better to appreciate on power Doppler (Fig. 2). These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of a vascular malformation. However, the duration of the progression of the supposed vascular malformation and the absence of phleboliths on the ultrasound and the subsequent X-ray raised suspicion regarding the diagnosis of a vascular malformation. A second differential of a neurofibroma was considered. Subsequently, a biopsy was conducted. It showed elongated spindle cells with poorly defined, pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and tapering, wavy, or buckled nuclei admixed with a few small nerve fibres (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemistry showed positivity for S-100 (Fig. 4). These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of diffuse neurofibroma.

Fig. 1.

Shows an ill-defined hyperechoic lesion around the ankle and the heel with multiple interspersed hypoechoic areas within it

Fig. 2.

On colour Doppler evaluation, these hypoechoic areas showed vascular flow. However, no phleboliths were noted within the lesion

Fig. 3.

Microscopic tissue section shows elongated spindle cells with poorly defined, pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and tapering, wavy, or buckled nuclei admixed with a few small nerve fibres. Haematoxylin and Eosin × 40 ×

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemistry shows diffuse cytoplasmic positivity. IHC S-100 × 40 ×

Discussion

Diffuse neurofibroma is a rare subtype of neurofibroma that predominantly affects children and young adults [4, 5]. It usually affects the skin and the subcutaneous tissue of the head and neck region, the trunk, and the extremities, and essentially comprises benign tumours with rare malignant transformations [4–7]. The extension of these tumours to the deeper tissues is relatively rare. The incidence of neurofibromatosis in patients presenting with diffuse neurofibromas is estimated to be around 10% [7]. However, a few conflicting reports suggest that the incidence of neurofibromatosis in these patients is higher mainly because these lesions affect children and young adults when the stigmata of the disease might not yet have fully developed.

Though literature on this tumour has been published widely in pathology, it remains largely unreported in imaging literature [4, 5]. Mostly isolated case reports are available; however, in recent times, a few case series have been published that define the ultrasonographic and magnetic resonance imaging findings of these lesions [1, 4]. One of the case series is entirely dedicated to the overlapping features of these diffuse neurofibromas and vascular malformations, which were observed in the present case [3].

On ultrasonography, the superficial subcutaneous lesions appear to be hyperechoic masses fenestrated by hypoechoic foci that represent the blood vessels [1, 4]. Similar findings were noted in the present case. However, few reported cases show deeper involvement of the structures, presenting as hypoechoic masses infiltrating the adjacent structures [4]. Ultrasound has been agreed upon as the initial modality of investigation due to its easy availability, lack of radiation exposure, and cost-effectiveness [1, 3, 4]. However, more deeply infiltrating lesions may require an MRI to delineate their exact extents. On MRI, most of these lesions are depicted as isointense or mildly hyperintense compared to muscle on T1-weighted images and mildly or markedly hyperintense compared to muscle on T2-weighted images. Such findings have been consistently described in various case reports [4, 8].

Hence, it can be deduced that the most common feature of any diffuse neurofibroma is an infiltrative plaque-like growth pattern with an increase in vascularity affecting the cutaneous and subcutaneous region. The close differentials for lesions of this type include angiomatous lesions such as haemangioma, angiolipoma, and angiomyolipoma, and cutaneous lymphoma. Rarely, cellulitis and haemorrhage may also mimic such lesions [1, 3, 4].

Treatment usually entails surgery. Since these lesions cannot be delineated from the underlying nerve, it invariably must be sacrificed. Deeper and larger lesions are managed by debulking surgery. Diffuse neurofibromas may recur owing to their infiltrative nature [2, 5].

Conclusion

To conclude, diffuse neurofibroma is a rare neurofibroma subtype and is often not associated with neurofibromatosis. In addition, its ambiguous imaging appearance is misleading and may push the diagnosis towards a vascular malformation. Hence, knowledge of this entity and its imaging characteristics would lead to timely diagnosis and appropriate subsequent management.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

References

- 1.Chen W, Jia JW, Wang JR. Soft tissue diffuse neurofibromas: sonographic findings. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:513–518. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphey MD, Smith WS, Smith SE, et al. Imaging of musculoskeletal neurogenic tumors: radiologic-pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 1999;19:1253–1280. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.5.g99se101253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yilmaz S, Ozolek AJ, Zammerilla L, et al. Neurofibromas with imaging characteristics resembling vascular anomalies. AJR. 2014;203:W697–W705. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.12409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassell DS, Bancroft LW, Kransdorf MJ, et al. Imaging appearance of diffuse neurofibroma. AJR. 2008;190:582–588. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramkumar G, Sudha V, Subbiah S, et al. A rare case of diffuse neurofibroma—a case report. Int J Curr Res Rev. 2015;7(2):69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kransdorf MJ, Murphey (2006) Neurogenic tumors. In: Pine JW (ed) Imaging of soft tissue tumors, vol 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 334–338

- 7.Van Zuuren EJ, Posma AN. Diffuse neurofibroma on the lower back. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:938–940. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beggs I, Gilmour HM, Davie RM. Diffuse neurofibroma of the ankle. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:755–759. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(98)80319-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]