Abstract

Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis (ECCL) or Haberland syndrome is an uncommon sporadic neurocutaneous syndrome of unknown origin. The rarity and common ignorance of the condition often makes diagnosis difficult. The hallmark of this syndrome is the triad of skin, ocular and central nervous system (CNS) involvement and includes a long list of combination of conditions. Herein we report a case of a 5-month-old male child who presented to our centre with complaint of seizure. The patient had various cutaneous and ocular stigmatas of the disease in the form of patchy alopecia of the scalp, right-sided limbal dermoid and a nodular skin tag near the lateral canthus of the right eye. MRI of the brain was conducted which revealed intracranial lipoma and arachnoid cyst. The constellation of signs and symptoms along with the skin, ocular and CNS findings led to the diagnosis of ECCL.

Keywords: Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis, Haberland syndrome, neurocutaneous syndrome

Introduction

Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis (ECCL) or Haberland syndrome was first described by Haberland and Perou in 1970.1 It is also known as Fishman’s syndrome.2 It is a rare neurocutaneous syndrome characterised by a unique triad of unilateral cutaneous lesions like lipomas, connective tissue nevi and alopecia, in association with ipsilateral ophthalmologic and neurological malformations.1,3 Since its first description in 1970, not more than 54 cases have been reported.1,3,4

Case report

A 5-month-old male child presented to the paediatric outpatient department (OPD) with the complaint of multiple episodes of generalised tonic-clonic seizures for two months. The child was born at term after an uncomplicated delivery to unrelated healthy parents. The neonatal period was uneventful.

On general examination there were patchy areas of alopecia involving the scalp. A limbal dermoid was present in the right eye with a nodular skin tag near the lateral canthus of the right eye. These lesions were present since birth, were non-tender and showed no significant increase in size over time.

Growth and developmental milestones were normal for the age. There was no significant family history with one absolutely normal elder male sibling. The rest of the systemic examination revealed no significant abnormality. Electrocardiogram and chest radiography were normal. Complete blood counts and other biochemical examination were within reference levels.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was advised to ascertain the cause of seizures. A lesion was seen within the right Meckel’s cave appearing hyperintense on T1-weighted imaging (WI)/T2WI showing suppression of signal intensity on T1 fat-suppressed sequences indicating fatty nature. A diagnosis of Meckel’s cave lipoma was made (Figure 1). Also an ill-defined, homogeneous, similar fat signal intensity lesion was seen involving the soft tissue planes of the right upper face and lateral half of the right eye. On post-contrast scans no significant contrast enhancement was seen suggestive of subcutaneous lipoma. A well-defined extra-axial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) intensity lesion was noted in the right temporal region appearing hyperintense on T2WI with suppression on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences with no evidence of restriction on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) suggestive of an arachnoid cyst (Figure 2). There was also partial volume loss of the right cerebral hemisphere predominantly affecting the right temporal lobe. Pulling of the ventricles and minimal midline shift towards the right suggested atrophic changes (Figure 3).

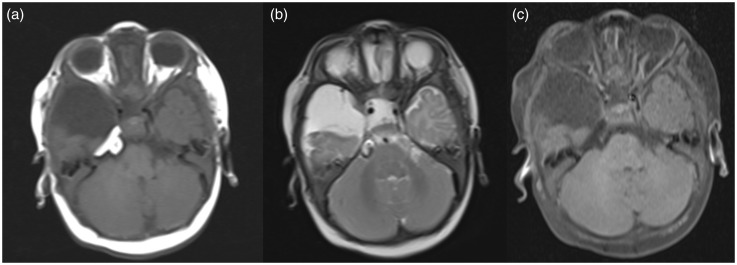

Figure 1.

A lesion within the right Meckel’s cave appearing hyperintense on T1-weighted imaging (WI) (a) and T2WI (b) showing suppression of signal intensity on T1 fat-suppressed sequences (c), suggesting diagnosis of Meckel’s cave lipoma. Also subcutaneous lipoma is seen over the right temporal region.

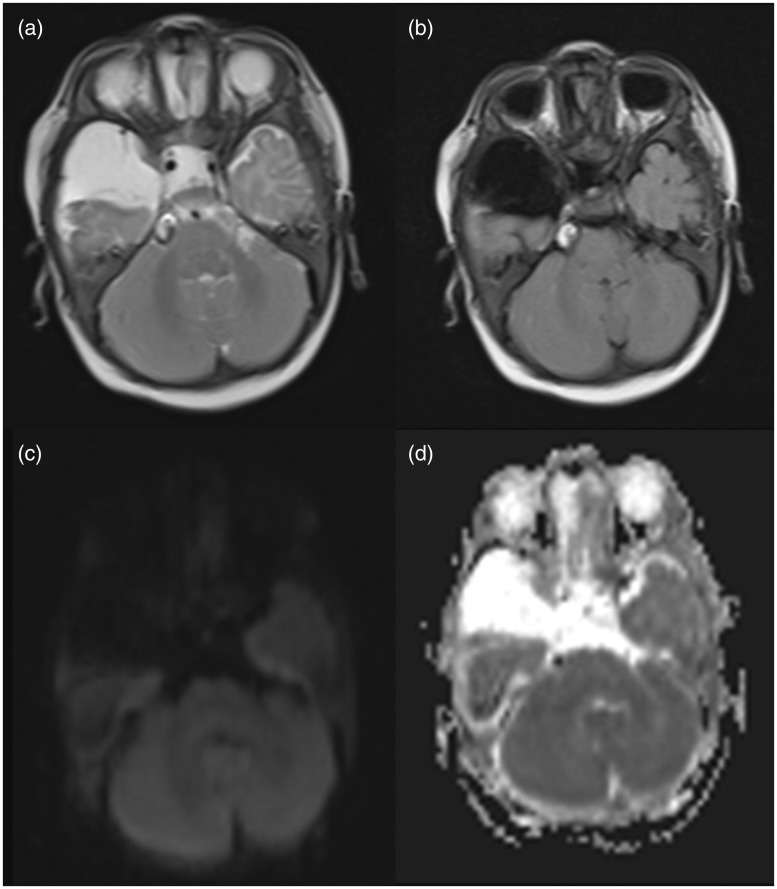

Figure 2.

A well-defined extra-axial CSF intensity lesion was noted in the right temporal region appearing hyperintense on T2WI (a) with suppression on FLAIR sequences (b) with no evidence of restriction on DWI (c) and ADC (d) suggestive of an arachnoid cyst. CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; T2WI: T2-weighted imaging; FLAIR: fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; ADC: apparent diffusion coefficient.

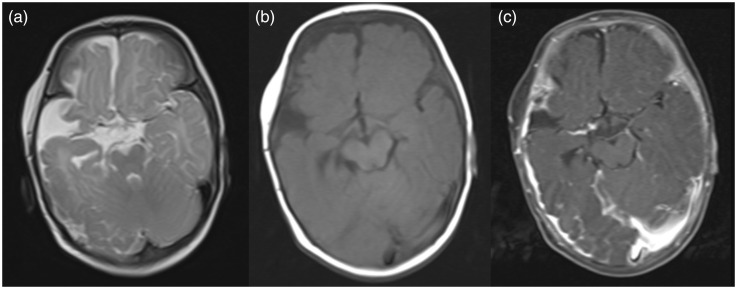

Figure 3.

(a)–(c) T2WI, T1WI and post-contrast fat-suppressed sequences show partial volume loss of the right cerebral hemisphere predominantly affecting the right temporal lobe with pulling of the ventricles and minimal midline shift towards the right suggesting atrophic changes. No focus of abnormal enhancement is seen. T2WI: T2-weighted imaging; T1WI: T1-weighted imaging.

Also X-rays of the jaw and the long bones were performed to rule out the common associations of cysts and none was found.

On the basis of history, clinical examination and MRI brain findings, a provisional diagnosis of ECCL was made. Taking into consideration the diagnostic criteria of ECCL proposed by Hunter5 and revised by Moog et al.,6,7 our case was diagnosed as a definite case of ECCL (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria of encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis (ECCL) (as proposed by Hunter5 in 2006 and modified by Moog6 in 2009).

| SYSTEM | MAJOR CRITERIA | MINOR CRITERIA |

|---|---|---|

| SKIN | Proven naevus psiloliparus (NP) Possible NP and >1 of the minor criteria 2–5. >2 Minor criteria 2–5 | 1-Possible NP 2-Patchy or streaky non-scarring alopecia without fatty naevus 3-Subcutaneous lipoma(s) in fronto-temporal region 4-Focal skin aplasia/Hypoplasia on scalp 5-Small nodular skin tags on eyelids or between outer canthus and tragus |

| EYE | Choristoma with or without associated anomalies | Corneal and other anterior chamber anomalies Ocular and eyelid coloboma Calcification of globe. |

| CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM | Intracranial lipoma Intraspinal lipoma Two of the minor criteria | Abnormal intracranial vessels, e.g. angioma, excessive vessels Arachnoid cyst or other abnormalities of meninges Complete or partial atrophy of hemisphere Porencephalic cysts(s) Asymmetrically dilated ventricles or hydrocephalous Calcification (not basal ganglia) |

| OTHER SYSTEM | Jaw tumour (osteoma, odontoma, ossifying fibroma. Multiple bone cyst Coarctation of aorta |

Table 2.

Application of criteria for diagnosis of encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis (ECCL).

| DEFINITE CASE | PROBABLE CASE |

|---|---|

| 1. Three systems involved, major criteria >2, OR | 1. Two systems involved, major criteria in both. |

| 2. Three systems involved, proven naevus psiloliparus (NP) OR possible NP +>1 minor skin criteria 2–5. | 2. Two systems involved, proven or possible NP. |

| 3. Two systems involved with major criteria, one of which is proven NP OR possible NP +>1 of minor skin criteria 2–5. |

Anticonvulsants were started for symptomatic treatment of seizures. The patient responded well to the anticonvulsant therapy. The nodular skin tag was excised. Histopathological examination of the nodular skin lesion was performed which showed disorganised elements of fibrous and adipose tissue proving it to be a lipomatous hamartoma. As ocular lesions were not encroaching upon the visual area and the child had normal visual acuity for age, these lesions were left untouched. The parents were properly counselled, and the nature of the disease and prognosis was explained to them. A proper follow-up was advised. Currently, the patient’s seizures are well controlled and the child is thriving.

Discussion

ECCL is a rare congenital neurocutaneous syndrome. Since its first description in 1970 by Haberland and Perou, not more than 54 cases have been described in literature till now.1 The exact embryological and molecular defect responsible is yet not known; however, certain mechanisms such as ectodermal dysgenesis and mosaicism are thought to be responsible for a mutated autosomal gene leading to mesenchymal tumours and vasculogenesis.8,9All of the reported cases were sporadic and no evidence of genetic transmission is reported as yet.8–10 The tissues affected in ECCL are the neural crest derivatives, skin elements, i.e. dermis and hypodermis of face and neck, head mesenchyme, dermal bones of the skull, truncoconal septum, odontoblasts and melanocytes.8,9,11

A hallmark of the disease is the triad of cutaneous, ocular and central nervous system (CNS) involvement. Most of the findings are usually unilateral with only a few cases reported with bilateral involvement.1,8,9

Though a varied spectrum of skin and ocular manifestations are seen in this syndrome both in their severity and extent, these manifestations are quite unique and consistent. The spectrum of neurodevelopmental involvement is also extremely wide ranging from completely normal mental status to severe mental retardation.8,10 Other CNS symptoms include seizure, hemiplegia, facial palsy, spasticity of contralateral limb, behavioural changes and sensorineural hearing loss.8,9

Non-scarring alopecia and naevus psiloliparus are the most common skin manifestations.8–10 Naevus psiloliparus are considered as a cutaneous hallmark of the syndrome. They are most commonly seen in the fronto-temporal and zygomatic regions and are usually evident since birth. Angiolipomas, fibrolipomas, connective tissue nevi and mixed hamartoma of fat, cartilage and other connective tissue are some of the other skin lesions which can be seen in this syndrome predominantly on the face, scalp and neck.6,8

Choristomas which are congenital hamartomatous lesions like epibulbar and limbal dermoid, lipodermoid and small skin nodules around the eyelids are the most characteristic ocular anomaly.8,9,11 They may be associated with corneal and anterior chamber anomalies, colobomas, microphthalmia, and calcification of the globe. Rarely persistent posterior hyaloid artery, a small tag in the anterior chamber, dysplastic iris, papilledema, hypertelorism and epicanthus inversus may also be seen.8,10,11

Diverse CNS anomalies have been described including cranial and spinal lipomas, asymmetric cerebral atrophy, and various cysts. Porencephalic cyst is the most commonly encountered CNS abnormality on imaging.8 The other abnormalities include arachnoid cyst, enlargement of the lateral ventricle, widening of the subarachnoid spaces, lack of normal insular opercularisation, a dysplastic cortex, corticopial calcifications, thinning and agenesis of the corpus callosum, intracranial lipoma and leptomeningeal angiomatosis.8,9

The original diagnostic criteria for ECCL were proposed by Hunter in 2006.5 The revised criteria were given by Moog in 2009 for definite/proven and possible ECCL cases and excludes the third group of probable ECCL as given by Hunter.5–7 In the revised criteria for ECCL, there are one major and three minor criteria involving the ocular system, three major and five minor criteria involving the cutaneous system, and three major and six minor criteria for CNS involvement.6 Three major criteria are also seen involving the other systems.

The differential diagnosis includes other rare neurocutaneous syndromes such as sebaceous naevus syndrome, Proteus syndrome, oculocerebrocutaneous syndrome (OCC), Sturge Weber syndrome (SWS) and hemimegalencephaly.8,9,11

Clinically ECCL may mimic sebaceous nevus syndrome, Proteus syndrome and OCC syndrome. Patients with sebaceous nevus syndrome also present with seizures and mental retardation, but the cutaneous lesions are characteristically on the midline of the face.1,5,8 However, the facial midline was preserved in our case. Proteus syndrome is characterised by progressive, bilateral, and asymmetric occurrence and usually involves the head, trunk and limbs. Brain abnormalities in Proteus syndrome are rare, which is an important differentiating feature from ECCL.8,9

The radiological differential diagnosis for ECCL includes SWS and hemimegalencephaly. In SWS the mesodermal dysgenesis mainly involves blood vessels, whereas fat tissue is primarily involved in ECCL. In ECCL, cerebral calcifications are distributed diffusely throughout the cortex, whereas in SWS occipito-parietal areas are mainly affected. Also these cortical calcifications can be found as early as in the first months of life in ECCL whereas in SWS they are seldom evident before 1 year of age.8,9 Hemimegalencephaly is characterised by overgrowth of one cerebral hemisphere and ipsilateral lateral ventricle. However, in ECCL the affected hemisphere is atrophic and the lateral ventricle appears enlarged secondary to atrophic changes.9,10 Also, neither intracranial lipomas nor arachnoid cysts occur in SWS or in hemimegalencephaly which are characteristic features of ECCL.8,9

As far as management is concerned, there is no specific treatment available for ECCL.8,9,11 The patient is managed symptomatically. As in our case anticonvulsants are started and surgical correction of ocular and cutaneous lesions is advised. Knowledge of this syndrome can lead to early diagnosis and early symptomatic management of the skin and ocular conditions so as to ensure as normal a life as possible for the patient without gross deformities.8,9

Conclusion

ECCL is a rare syndrome with multi-system involvement. The identification of the more obvious skin and ocular lesions is of paramount importance to lead to more ominous CNS manifestations. An early and accurate diagnosis can go a long way towards improved symptomatic patient care and hence a better quality of life for the patient and the caregivers equally.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Haberland C, Perou M. Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis: A new example of ectomesodermal dysgenesis. Arch Neurol 1970; 22: 144–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fishman MA, Chang CS, Miller JE. Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis. Pediatrics 1978; 61: 580–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Happle R, Kuster W. Nevus psiloliparus: A distinct fatty tissue nevus. Dermatology 1998; 197: 6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parazzini C, Triulzi F, Russo G, et al. Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis: Complete neuroradiologic evaluation and follow-up of two cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999; 20: 173–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunter AG. Oculocerebrocutaneous and encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis syndromes: Blind men and an elephant or separate syndromes? Am J Med Genet A 2006; 140: 709–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moog U. Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis. J Med Genet 2009; 46: 721–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moog U, Jones MC, Viskochil DH, et al. Brain anomalies in encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis. Am J Med Genet Part A 2007; 143: 2963–2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thakur S, Thakur V, Sood RG, et al. Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis with calvarial exostosis – Case report and review of literature. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2013; 23: 333–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koti K, Bhimireddy V, Dandamudi S, et al. Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis (Haberland syndrome): A case report and review of literature. Indian J Dermatol 2013; 58: 232–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naous A, Shatila AR, Naja Z, et al. Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis: A rare association with tethered spinal cord syndrome with review of literature. Child Neurol Open 2015; 2: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan CC, Chen JS, Chu CY. Haberland syndrome. Dermatol Sinica 2005; 23: 41–45. [Google Scholar]