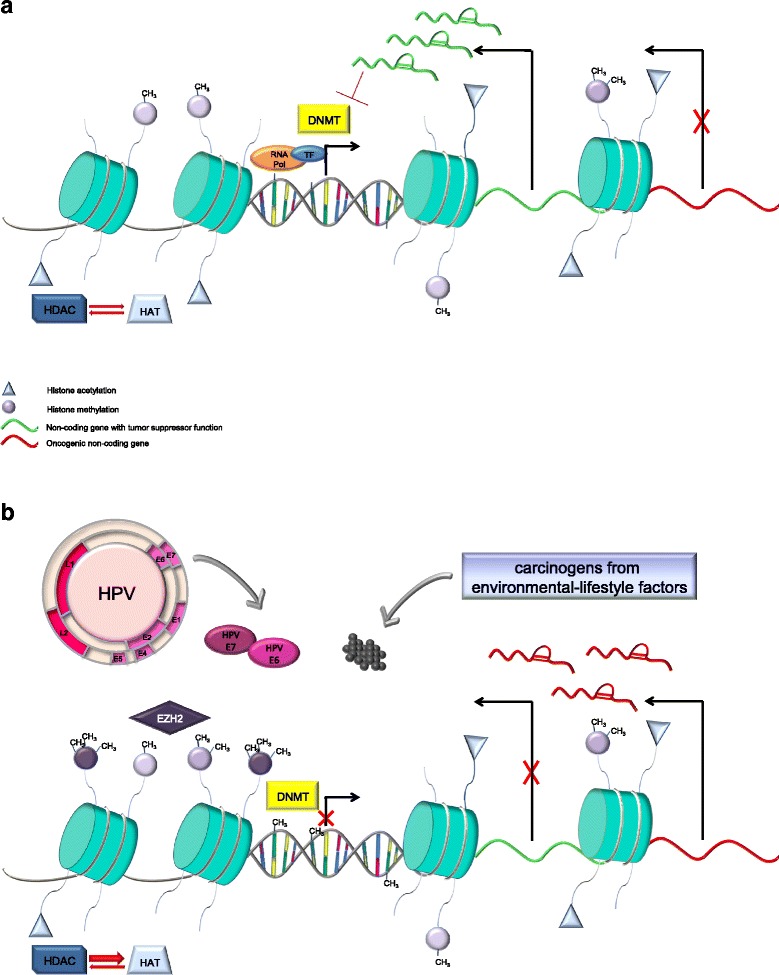

Fig. 1.

Epigenetic regulation of gene expression involves the crosstalk of DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA (ncRNAs). In normal cells (a), CpG within promoter regions of tumor suppressor genes (TSG) are not methylated and are occupied by complexes including RNA polymerase (RNA pol) and transcription factors (TF), thus allowing gene transcription. Histones undergo several post-translational modifications on their N-terminal tails, including acetylation and methylation. Histone acetylation is the result of the dynamic interplay between histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), and acetylated histones have been associated with actively expressed genes. Unlike histone acetylation, methylation of histone proteins can result in both repressive or promoting effects on transcription, depending on which residue is modified. NcRNAs, which are involved in almost all major cellular functions, may function either as oncogenes or as TSG. NcRNAs whose expression is increased in tumors may be considered as oncogenes, whereas ncRNAs whose expression is decreased in tumor cells are considered TSG. NcRNAs can also regulate the expression and/or the activity of the epigenetic enzymes, such as DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs). In oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (b), the epigenetic state of cells changes in response to HPV infection and environmental-lifestyle factors (i.e., tobacco smoke and/or excessive alcohol intake). The result is the accumulation of several aberrant epigenetic modifications that lead to inappropriate activation or inhibition of key signaling pathways. For example, E6 and E7 HPV oncoproteins and carcinogens from cigarettes and alcohol have been demonstrated to affect histone acetylation and methylation patterns either by directly interacting with epigenetic enzymes [i.e., DNMT, enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2)] or by modulating the ncRNA landscape