Abstract

Background

The lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning (LGBTQ) population is at higher risk for multiple types of cancers compared with the heterosexual population. Expert NCCN panels lead the nation in establishing clinical practice guidelines addressing cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment of cancer sites and populations. Given the emergence of new data identifying cancer dis- parities in the LGBTQ population, this study examined the inclusion of medical and/or psychosocial criteria unique to LGBTQ within NCCN Guidelines.

Methods

Data were collected for 32 of the 50 NCCN Guidelines.

Results

NCCN panel members reported that neither sexual orientation (84%) nor gender identity (94%) were relevant to the focus of their guidelines; 77% responded that their panels currently do not address LGBTQ issues, with no plans to address them in the future.

Conclusions

Greater consideration should be given to the needs of LGBTQ patients across the cancer care continuum. Given that research concerning LGBTQ and cancer is in its infancy, additional empirical and evidence-based data are needed to bolster further integration of LGBTQ-specific criteria into clinical care guidelines.

Background

The lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning (LGBTQ) population, also known as sexual and gender minorities (SGMs), is at higher risk for multiple types of cancers compared to heterosexual and cisgender populations attributed to, in part, an elevated prevalence of risk behaviors and risk factors among SGM individuals.1 For example, higher rates of human papillomavirus (HPV) in the SGM population contribute to increased incidence of anal cancer among men who have sex with men (MSM) as compared to heterosexual men2 as well as higher rates of cervical cancer risk factors and behaviors in lesbian women when compared to heterosexual women.3 There is speculation that higher smoking rates in the SGM community may lead to an elevated risk of tobacco-related diseases such as lung cancer, though there is not yet sufficient data on rates of lung cancer among SGMs. Collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data is currently not standard, and these data are not in SEER or other national datasets. Thus, SGM populations have not been followed over time to determine the rates of emergence of new cases of cancer, these and other areas need immediate and careful monitoring. SGMs are less likely to seek cancer screening,5 face multiple structural, cognitive and social barriers that decrease the likelihood of screening, 5–7 and are more likely to be economically disadvantaged, underinsured and to underutilize health care8 and to have poorer cancer-related outcomes. 1

Despite the impact cancer has on the SGM population, a previous study found that the majority of surveyed oncologists lacked knowledge regarding SGM health-related issues and did not inquire about patients’ sexual orientation and gender identity.9 The multidisciplinary expert panels of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) lead the nation in establishing Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for numerous cancer sites and populations.10 Given the emerging body of research identifying cancer disparities in the SGM population, we conducted a national survey of the NCCN Guidelines Panels to assess whether medical and psychosocial issues unique to SGM populations are addressed or will be addressed in the future.

Methods

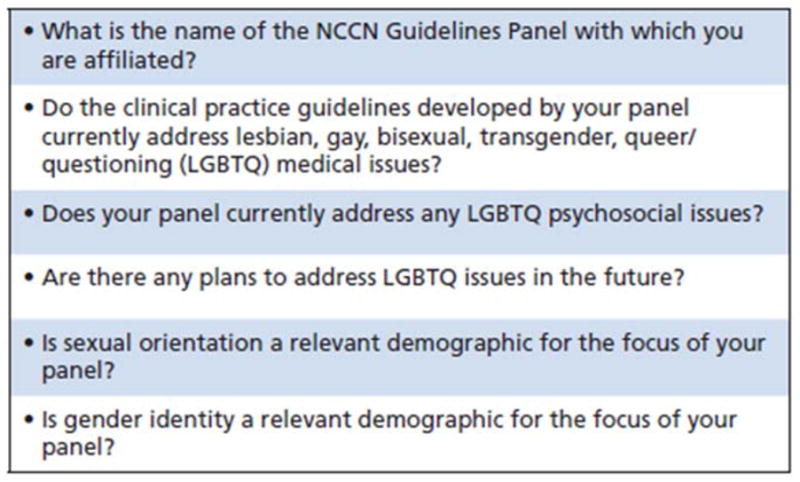

Study approval was obtained from Chesapeake Institutional Review Board (Columbia, MD). Chairpersons for each of the NCCN Guideline Panels10 (n=50) were emailed an invitation to participate in the study. A link embedded within the email routed participants to a short web-based survey (Figure 1) that assessed (Table 1) each panel’s current practices and/or future plans for addressing medical and psychological issues relevant to LGBTQ individuals, including, the relevance of patients’ sexual orientation or gender identity, to the focus of the panel. Published guidelines for all 50 panels were independently reviewed by two members of the research staff to assess the presence of any content specific to SGM populations. Survey responses were reported using descriptive statistics. Of the 50 NCCN Guidelines Panels, we received responses from 31 Guidelines Panels for a response rate of 62%. We note that several chairs served on more than one panel and submitted responses for each panel on which they served.

Figure 1.

NCCN Panel Member survey.

Table 1.

Aggregate Results of NCCN Guideline Panels

| NCCN Guidelines Panel Groupinga | Do the Clinical Practice Guidelines Developed by Your Panel Currently Address LGBTQ Medical Issues? | Do the Clinical Practice Guidelines Developed by Your Panel Currently Address LGBTQ Psychosocial Issues? | Is Sexual Orientation a Relevant Demographic for the Focus of Your Panel? | Is Gender Identity a Relevant Demographic for the Focus of Your Panel? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Yes | No, But Plan on Addressing Them in the Future | No, and Do Not Intend on Addressing Them in the Future | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Cancer by site | 4 | 0 | 14 | 3 | 15 | 2 | 16 | 1 | 17 |

|

| |||||||||

| Detection, Prevention, & Risk Reduction | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

|

| |||||||||

| Supportive Care & Age-Related | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 |

NCCN panel groupings were based on NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology groupings on NCCN.org.

Results

Of the 31 responses, 87% of NCCN chairs self-reported sexual orientation was not relevant to the focus of their panels and 90% reported gender identity was not relevant. Eight chairs reported their clinical guidelines did address LGBTQ medical or psychosocial issues. Conversely, 87% of NCCN panel chairs responded that their panels currently did not address LGBTQ medical or psychosocial issues, with no plans to do so in the future. Ten percent of panel chairs noted that while their respective panels did not presently address LGBTQ medical and psychosocial issues, they planned to do so in the future. Non-respondent NCCN Guideline Panels are presented in Table 2. A review of each responding panels’ actual guidelines showed only the Anal Cancer Guidelines panel had specific language pertaining to SGMs patients.

Discussion/Implications

Results from our survey demonstrate that integration of SGM-specific issues has not yet reached NCCN panels, perhaps because SGM cancer research is still emerging. Although the majority of respondents indicated that their panels did not address LGBTQ medical and psychosocial issues, with no plans to address them in the future, there were promising exceptions. Similarly, several panel chairs acknowledged the importance of sexual orientation and/or gender identity to the focus of their panels. These data represent an auspicious start to the creation of policy addressing the unique needs of SGM across the cancer continuum.

Direct applicability of SGM-related issues may be more readily apparent to Panel Chairs depending on the specialty, especially for panels associated with cancer sites for which evidence-based research has demonstrated an SGM-related disparity. For example, the Anal Cancer Guidelines Panel addresses higher incidence of anal cancer among men who have sex with men (MSM) and recommends HPV vaccination for this population.

It can be argued, however, that consideration of SGM issues has relevance across all NCCN panels and represents best practice in patient care. Indeed, knowledge of patients’ SOGI is a relevant factor to facilitate in identifying risk factors for effective cancer primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. SGM individuals face unique challenges throughout the course of the cancer care continuum, particularly related to sexual functioning, social support and access to health care. Providers should not assume heteronormativity when interacting with patients, actively cultivate an environment that encourages disclosure of SOGI and recognize that SGMs have unique medical needs.11–13 Consideration of the unique medical and psychosocial needs of SGM populations should be routinely integrated into clinical practice guidelines in the oncology care setting. Establishing standardized guidelines to improve providers’ knowledge about cancer risk in the SGM population will likely improve quality of care for SGM individuals.

Review of the clinical guidelines for all responding NCCN panels revealed only the Anal Cancer Guidelines Panel’s guidelines contained language specifically addressing the unique needs of the SGM-population. The Distress Management and Survivorship Panels’ guidelines did contain vague references to “sexuality” that were not referenced in the context of SGM-related health. Further research is needed to understand how panels reporting consideration of SGM- health related issues interpret this, as it was not apparent from their guidelines that SGM issues were addressed. Non-responses from key NCCN panel chairs is a limitation in this study, particularly among panels representing sites with cancer disparities in SGM populations, including prostate, and head and neck cancers.

Conclusion

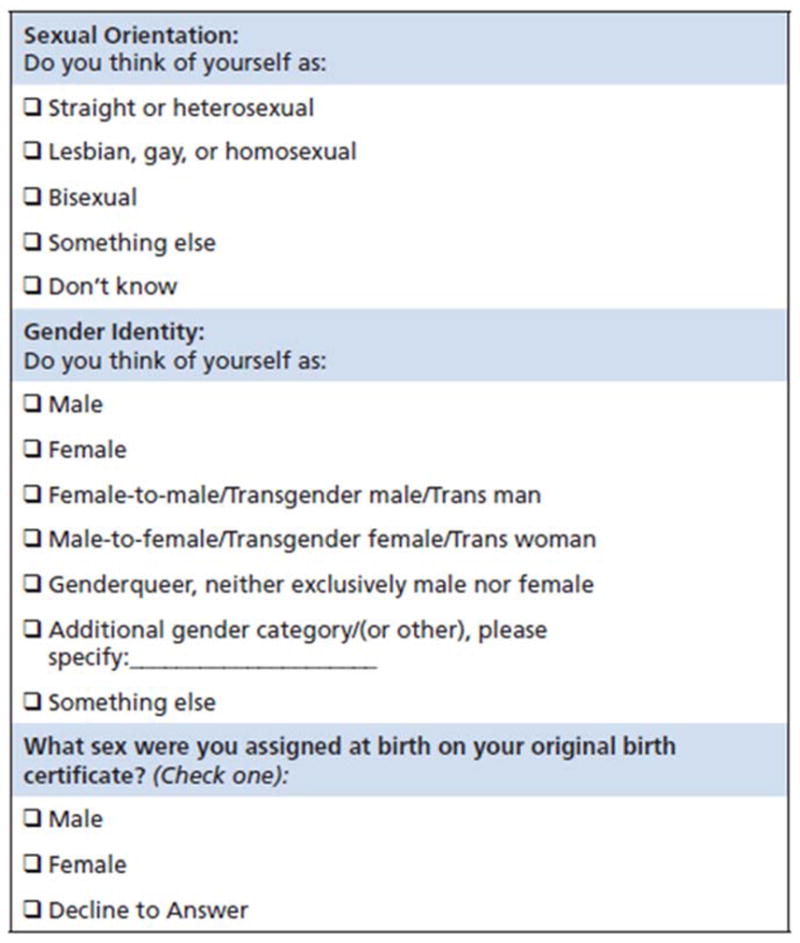

The results from our national survey demonstrated that NCCN Guidelines Panels are not addressing an emerging, underserved population. The landscape of SGM health is evolving as research and medical fields reveal the unique health needs and disparities of this population. Even as new research helps to shape the burgeoning research agenda, much is still unknown about the prevalence, risk, mortality and quality of life for SGM individuals with cancer. All panels should consider collecting proper SOGI data so that cancer-related issues (incidence, physical, QOL, outcomes, etc) of this under-represented population can be assessed and used to modify guidelines in the future. It is also suggested that the panels perform periodic literature reviews on SOGI studies related to their disease site to ensure they are up to date on the current status of SGM relative to the panel disease site. The Fenway Institute, National LGBT Health Education Center14 recommends the following means for collecting SOGI data in electronic medical records (Figure 2). Overall, NCCN Panel guidelines should reflect greater awareness of the medical and psychosocial needs of SGM individuals.

Figure 2.

Recommended data collection of sexual orientation and gender identity in electronic medical records.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Funded by a Miles for Moffitt Milestone Award (PIs: Quinn and Schabath) and a National Institute of Health R25T training grant (R25CA090314). This work has also been supported in part by a Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute; an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (grant number P30-CA76292).

References

- 1.Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, et al. Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2015;65(5):384–400. doi: 10.3322/caac.21288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Machalek DA, Poynten M, Jin F, et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection and associated neoplastic lesions in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet oncology. 2012;13(5):487–500. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waterman L, Voss J. HPV, cervical cancer risks, and barriers to care for lesbian women. Nurse Pract. 2015;40(1):46–53. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000457431.20036.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rath JM, Villanti AC, Rubenstein RA, Vallone DM. Tobacco use by sexual identity among young adults in the United States. nicotine & tobacco research. 2013:ntt062. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham R, Berkowitz B, Blum R, et al. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchmueller T, Carpenter CS. Disparities in health insurance coverage, access, and outcomes for individuals in same-sex versus different-sex relationships, 2000–2007. American journal of public health. 2010;100(3):489–495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.160804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamen CS, Smith-Stoner M, Heckler CE, Flannery M, Margolies L. Social support, self-rated health, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender identity disclosure to cancer care providers. Paper presented at: Oncology nursing forum; 2015; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Hoy-Ellis CP, Brown M. Cancer and the LGBT Community. Springer; 2015. Addressing Behavioral Cancer Risks from a LGBT Health Equity Perspective; pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shetty G, Sanchez JA, Lancaster JM, Wilson LE, Quinn GP, Schabath MB. Oncology healthcare providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors regarding LGBT health. Patient education and counseling. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines. 2014 https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines_nojava.asp.

- 11.American Academy of Family Physicians. [Accessed August 31, 2016];Recommended Curriculum Guidelines for Family Medicine Residents: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender Health. 2014 http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/medical_education_residency/program_directors/Reprint289D_LGBT.pdf.

- 12.Margolies L. The psychosocial needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender patients with cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2014;18:462–464. doi: 10.1188/14.CJON.462-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oncology Nursing Society. [Accessed August 31,2016];ONS Endorses the American Academy of Nursing Policy Brief on Support for the Rights of LGBT Individuals Who Are Hospitalized. 2015 https://www.ons.org/newsroom/news/ons-endorses-american-academy-nursing-statement-

- 14.Bradford J, Cahill S, Grasso C, Makadon H. How to gather data on sexual orientation and gender identity in clinical settings. Boston, MA: The Fenway Institute; 2012. Retrieved from www.fenwayhealth.org. [Google Scholar]