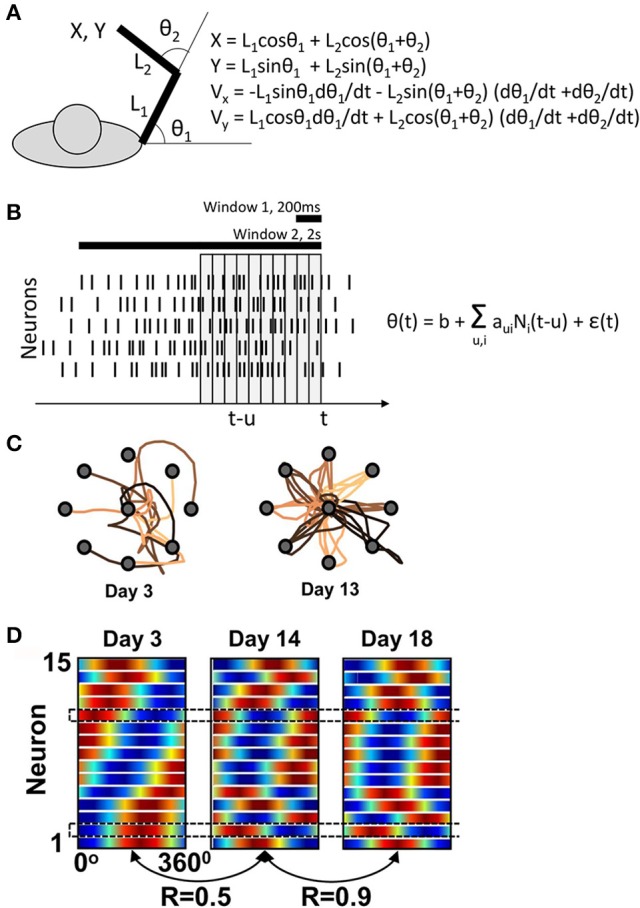

Figure 1.

Ganguly and Carmena's experiment. (A) Task schematics. The behavioral apparatus suspended the arm in a horizontal plain. Monkeys were free to flex and extend their shoulder and elbow to control the cursor coordinates, defined by the center of the hand. On the right, the equations are shown for the translation of joint angles into the cursor Cartesian coordinates. (B) Schematics of the BMI decoder, which was composed of two Wiener filters converting neuronal activity into the shoulder and elbow angles. The decoders contained ten 100-ms taps and were trained on the manual performance in a center-out task. For BMI control, the monkeys' arms were isometrically restrained. Horizontal bars illustrate the time windows (200 ms and 2s) that Ganguly and Carmena used in their directional tuning analyses. None of these analyses matched the tap structure of the decoder. (C) Examples of cursor trajectories on different training days. (D) Directional tuning analysis using a 200-ms window representing the initial portion of cursor movement from the screen center to the target. Directional tuning characteristics for different neurons (horizontal lines) are represented by sinusoids fitted to neuronal data. The color plots are normalized to have the same minimal and maximal values for all neurons. With this representation, tuning depths cannot be compared across neurons or different training days. (C) and (D) are adapted from Ganguly and Carmena (2009).