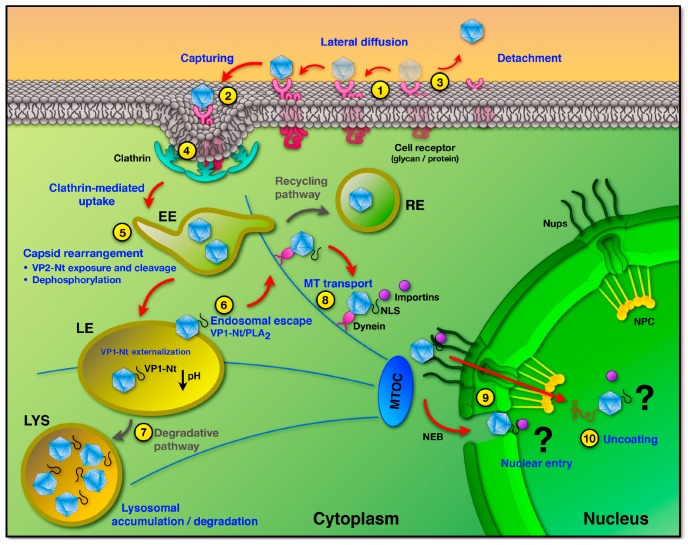

Figure 4.

Model of PtPV cell entry and nuclear import. In the productive infection, PtPV capsids bind to one or more cell receptors (1). Following lateral diffusion, capsids are captured by pre-formed or forming clathrin pits (2). Or otherwise become detached from their receptors (3). Capsids are internalized via clathrin-mediated endocytosis (4) and enter the endocytic pathway where the low pH environment and local enzymes trigger structural rearrangements (5). Major structural changes are de novo VP2-Nt exposure and cleavage and particle dephosphorylation, leading to VP1-Nt (or VP1uR) exposure through the channel. The endosomal trafficking may vary in complexity and time, but commonly only a small proportion of particles escape after altering the endosomal membrane through the activity of the VP1-encoded phospholipase A2 (6). Many incoming infectious particles fail to escape from endosomes and are routed to and accumulated in the degradative lysosomes (7). In the cytosol, PtPV exploit the cytoskeleton and motor proteins to move to the nuclear vicinity (8). It is not yet clear how the viruses and/or their genomes enter the nucleus, as nuclear pore-dependent entry and permeabilization of the nuclear envelope have been proposed (9). The site and timing of capsid uncoating are also uncertain processes. Growing evidences suggest that capsids remain assembled in the cytosol and enter the nucleus intact, and the uncoating would take place during the interaction with NPC proteins and/or following nuclear entry (10).