This case series describes the clinical presentation of optic nerve infiltration, its imaging characteristics, and outcomes in patients with primary central nervous system lymphomas.

Key Points

Questions

What is the presentation of lymphomatous optic nerve infiltration, and what is the outcome of this condition?

Findings

This case series from a cohort of 752 patients with primary central nervous system lymphomas identified 7 with lymphomatous optic nerve infiltration. All presented with rapidly progressive and severe visual impairment; clinical outcome was poor despite chemotherapy.

Meaning

Lymphomatous infiltration of the optic nerve is rare and may lead to poor visual functional outcome.

Abstract

Importance

Visual impairment in primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is caused mostly by intraocular lymphomatous involvement (vitritis and retinal infiltration), whereas optic nerve infiltration (ONI) is a rare condition.

Objective

To describe the clinical presentation of ONI, its imaging characteristics, and outcome.

Design, Setting and Participants

A total of 752 patients diagnosed with PCNSL were retrospectively identified from the databases of 3 French hospitals from January 1, 1998, through December 31, 2014. Of these, 7 patients had documented ONI. Exclusion criteria were intraocular involvement, orbital lymphoma, or other systemic lymphoma. Clinical presentation, neuroimaging, biological features, treatment, and outcomes were assessed.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Treatment response was evaluated clinically and radiologically on follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) according to the International PCNSL Collaborative Group response criteria.

Results

The 7 patients included 5 women and 2 men. Median age at diagnosis was 65 years (range, 49-78 years). Two patients had initial ONI at diagnosis, and 5 had ONI at relapse. Clinical presentation was marked by rapidly progressive and severe visual impairment for all patients. The MRI findings showed optic nerve enlargement in 3 patients and contrast enhancement of the optic nerve in all patients. Additional CNS lesions were seen in 4 patients. Examination of cerebrospinal fluid samples detected lymphomatous meningitis in 2 patients. Clinical outcome was poor and marked by partial recovery for 2 patients and persistent severe low visual acuity or blindness for 5 patients. Median progression-free survival after optic nerve infiltration was 11 months (95% CI, 9-13 months), and median overall survival was 18 months (95% CI, 9-27 months).

Conclusions and Relevance

Optic nerve infiltration is an atypical and challenging presentation of PCNSL. Its visual and systemic prognosis is particularly poor compared with vitreoretinal lymphomas even in response to chemotherapy. Although intraocular involvement is frequent in PCNSL and clinically marked by slowly progressive visual deterioration, lymphomatous ONI is rare and characterized by rapidly progressive severe visual impairment.

Introduction

Ocular involvement, usually affecting the retina, the vitreous, or the optic nerve head, can be found in about 20% of patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL), whereas optic nerve infiltration (ONI) is a rare condition. Infrequently, choroidal lymphoma can extend to the optic nerve and the orbit.

Sporadic case reports on isolated ONI as the initial manifestation of PCNSL have been published. Another case report describes isolated infiltration of the visual pathways, and anecdotal observations describe contiguous ONI in primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. In systemic lymphoma, optic nerve involvement has been reported at initial presentation or at recurrence. The aim of the present study was to describe clinical and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) patterns of ONI in PCNSL, its course, and its prognosis after treatment in a retrospective case series.

Methods

Patients with ONI of PCNSL were retrospectively identified from the databases of the Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière in Paris, France; the Hôpital René-Huguenin–Institut Curie in Saint-Cloud, France; and the Hôpitaux Civils de Colmar in Colmar, France, from January 1, 1998, through December 31, 2014. We included patients with a pathologic diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell PCNSL and ONI identified at any time during the course of the disease on cerebral MRI. Optic nerve infiltration was not found in patients with other histologic subtypes of PCNSL. The MRI protocols included a minimum of T1- and T2-weighted sequences before and after gadolinium administration. Patients with vitreoretinal lymphoma, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, active systemic lymphoma, or other types of lymphoma were excluded. This study was approved by the ethics boards of the participating institutions, which waived the need for informed consent for this medical record review.

The patients’ clinical presentation, neuroimaging, and biological features were analyzed retrospectively from their medical records. Treatment response was evaluated clinically and radiologically on follow-up MRI according to the International PCNSL Collaborative Group response criteria. Progression-free and overall survival were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Features

A total of 752 patients diagnosed with PCNSL were identified from our databases, but only 7 (5 women and 2 men) had documented ONI. The median age at diagnosis of ONI was 65 years (range, 49-78 years). None of the 7 patients presented with ONI and ocular lymphoma. The clinical characteristics of the 7 patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients With ONI of PCNSL.

| Characteristic | Patient Dataa (N = 7) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 2 |

| Female | 5 |

| Age at ONI, median (range), y | 65 (49-78) |

| HIV infection | 0 |

| Timing of ONI | |

| At initial presentation | 2 |

| At first relapse | 4 |

| At second relapse | 1 |

| Clinical presentation | |

| Severe visual impairment (visual acuity, <1/10) | 7 |

| Time from initial symptoms to severe visual impairment, median (range), d | 14 (10-21) |

| Unilateral/bilateral visual impairment | 5/2 |

| Visual field defect, bitemporal hemianopia | 2 |

| Red eyes | 1 |

| Ocular or orbital pain | 2 |

| Headache | 3 |

| Vitreoretinal lymphoma | 0 |

| Other cranial nerve involvement | 1 |

| Lymphomatous meningitis | 2b |

| Systemic relapse | 0 |

| KPS score at ONI diagnosis, median (range)c | 60 (40-80) |

| Time from initial symptoms to treatment, median (range), d | 28 (10-140) |

| Misdiagnosis before diagnosis of ONI | |

| Giant cell arteritis | 1 |

| Nonorganic visual loss | 1 |

| Optic neuritis | 1 |

| Ocular lymphoma | 1 |

| Outcome | |

| Visual | |

| Partial recovery | 2 |

| Persisting severe low visual acuity or blindness (visual acuity <1/10) | 5 |

| Radiological | |

| Complete response | 4 |

| Partial response | 1 |

| Stable disease | 2 |

| PFS after ONI, median (95% CI), mo | 11 (9-13) |

| OS after ONI, median (95% CI), mo | 18 (9-27) |

Abbreviations: KPS, Karnofsky performance status; ONI, optic nerve infiltration; OS, overall survival; PCNSL, primary central nervous system lymphoma; PFS, progression-free survival.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as number of patients.

Includes 6 patients who underwent lumbar puncture.

Possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better health.

Two patients had ONI at initial diagnosis; 4 patients, at first relapse after high-dose methotrexate–based chemotherapy (4, 8, 11, and 12 months after initial diagnosis); and 1 patient, at the second relapse after initial high-dose methotrexate-based chemotherapy and salvage chemotherapy consisting of high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant (32 months after initial diagnosis). Optic nerve infiltration was revealed in all cases by subacute severe visual impairment defined as visual acuity of less than 1/10, unilateral in 5 cases, bilateral in 2 cases, and painless in 5 cases. Visual impairment reached a nadir within a median of 14 days. None of the patients was diagnosed with vitreoretinal lymphoma at any time during the course of their disease.

Neuroimaging

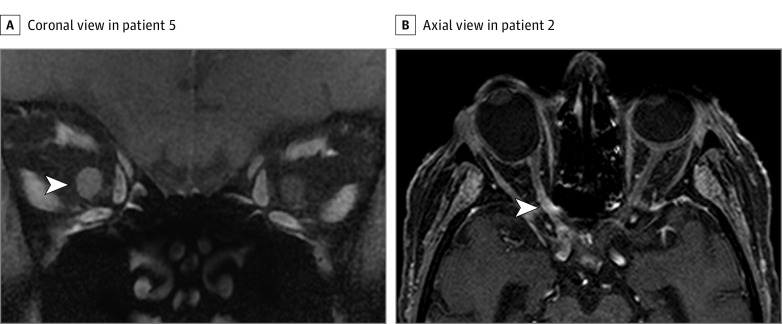

Magnetic resonance imaging showed contrast enhancement of the optic nerve in all 7 patients and optic nerve thickening in 3 (the MRIs of 2 patients presented in Figure 1). Patterns and locations of ONI are shown in Table 2. In addition, MRI of the brain revealed enhancing parenchymal lesions in 2 of 2 patients at initial presentation and in 1 of 5 patients at relapse. Diffuse nonenhancing lesions on T2-weighted sequences were observed in 1 of 5 patients at relapse.

Figure 1. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) in 2 Patients With Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma.

A, Coronal T1-weighted gadolinium-enhanced fat-saturated MRI demonstrates contrast enhancement of the entire right optic nerve in patient 5. Arrowhead points to the right optic nerve. B, Axial T1-weighted gadolinium-enhanced MRI with spectral presaturation with inversion recovery technique demonstrates contrast enhancement of the prechiasmatic and intracanalicular right optic nerve (patient 2). Arrowhead points to the intracanalicular right optic nerve.

Table 2. MRI Findings of ONI of PCNSL.

| Characteristic | No. of Patients |

|---|---|

| ONI type | |

| Unilateral | 5 |

| Bilateral | 2 |

| Location of ONI | |

| Chiasm | 3 |

| Prechiasmatic/cisternal | 4 |

| Intracanalicular | 4 |

| Intraorbital | 5 |

| Optic nerve enhancement | |

| Entire optic nerve | 4 |

| Optic nerve sheath | 3 |

| Optic nerve thickening | 3 |

| Brain MRI finding (apart from ONI) | |

| Normal or absence of new lesions | 3 |

| Enhancing lesions | 3 |

| New nonenhancing lesions on T2-weighted MRI | 1 |

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ONI, optic nerve infiltration; OS, overall survival; PCNSL, primary central nervous system lymphoma.

Cerebrospinal Fluid Findings and Other Investigations

Lymphomatous meningitis was found in the 2 patients with ONI at the initial presentation. At relapse, standard cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) indices were within reference limits in 4 patients (lumbar puncture was not performed in 1 patient). MicroRNAs (miRNAs) suggestive of PCNSL (miR-21, miR-19, and miR-92a) were found in the CSF samples of 3 patients.

Ophthalmologic evaluation (slitlamp and dilated fundus examinations) excluded intraocular involvement in all cases. Whole-body computed tomography (performed in 5 of 7 patients) and standard laboratory tests (white blood cell count and measurement of serum lactate dehydrogenase levels) yielded negative findings for systemic lymphoma. All patients were seronegative for HIV.

Initial Misdiagnoses and Final Diagnosis

In this cohort, 2 patients were diagnosed with ONI as the initial presentation of PCNCSL. Other diagnoses were first considered, including nonorganic visual loss for one patient and giant cell arteritis for the other patient. In the latter patient, meningioma of the optic nerve sheath was later suspected.

Diagnosis of ONI was established in both patients after the detection of asymptomatic contrast-enhancing parenchymal lesions on cerebral MRI and results of lumbar puncture proving lymphomatous meningitis. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and temporal artery biopsy disclosed no pathologic results in the second patient.

For the 5 patients presenting with ONI at relapse, this diagnosis was suspected immediately in 3. In 2 of these patients, cerebral MRI disclosed new parenchymal lesions (contrast enhancing in one and nonenhancing in the other). In the third patient, miRNA suggestive of PCNSL in the CSF and the negative findings of further extensive workup helped to establish the diagnosis of ONI.

In the 2 remaining patients with ONI identified at relapse, 2 differential diagnoses were discussed before ONI was proven: ocular lymphoma and optic neuritis. In the first patient, findings on standard MRI without sequences focused on the optic nerves were interpreted as normal. Vitrectomy was performed despite the normal ophthalmologic examination findings, and the results ruled out ocular lymphoma. In the second patient, comprehensive workup showed no abnormalities.

Results of a detailed biological workup performed in 2 of the 5 patients with ONI at relapse were negative. These workups included standard measurement of complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, renal and hepatic function, serum lactate dehydrogenase level, and serum protein electrophoresis; assessment for autoimmune disorders, including measurement of antinuclear antibodies, extractable nuclear antigens, and aquaporin-4 antibodies; assessment for infectious diseases, including Lyme disease, Bartonella species, syphilis, chlamydia, mycoplasma, hepatitis B and C viruses, HIV, enterovirus, and coxsackievirus; and CSF testing that included an oligoclonal band screen.

Therapeutic Management

The median duration of symptoms before treatment was 23 days (range, 10-140 days). High-dose, methotrexate-based polychemotherapy was used for the 2 patients in a first-line situation, and various salvage chemotherapy regimens were used at relapse in the other 5 patients. Rituximab treatment was administered to 3 patients (2 at ONI and 1 before ONI). Detailed treatment information is summarized in the eTable in the Supplement.

Prognosis and Follow-up

The median duration of follow-up was 13 months (range, 3-40 months). Visual outcome was poor; 5 of 7 patients had persisting severe low visual acuity or blindness (visual acuity, <1/10) without recovery, whereas 2 patients recovered partially (visual acuity, 3/10 and 6/10). For the latter 2 patients, the time from the onset of symptoms to treatment was short (10-21 days) (Table 1), and 1 of these patients received high-dose corticosteroids before chemotherapy. A complete radiological response, defined by disappearance of optic nerve enlargement and contrast enhancement, was observed in 4 of 7 patients, including the 2 patients with clinical improvement. A partial response, defined as a 50% decrease in optic nerve enhancement and enlargement, was noted in 1 of 7 patients, and stable disease (unchanged MRI findings) was noted in 2.

Relapse of lymphoma occurred in 5 of 7 patients. Only 1 patient had a relapse of ONI; 3 patients had an isolated CNS relapse, and 1 patient had CNS and brachial plexus relapse. One of these 5 patients received supportive care alone, whereas different chemotherapy regimens were administered to the other 4 patients (1 also received radiotherapy later). All 5 patients died of tumor progression.

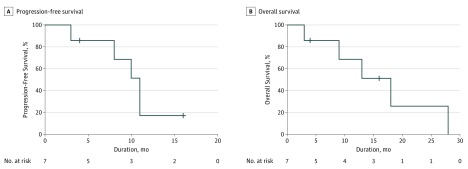

The patterns of relapse after treatment of ONI and outcome are summarized in the eTable in the Supplement. Median progression-free survival after ONI was 11 months (95% CI, 9-13 months); overall survival, 18 months (95% CI, 9-27 months) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Curves of Survival After Optic Nerve Infiltration (ONI).

Includes 7 patients with ONI. Median progression-free survival was 11 months (95% CI, 9-13 months); median overall survival, 18 months (95% CI, 9-27 months). Crosshatches indicate censored.

Discussion

Visual deterioration in patients with PCNSL is typically attributable to intraocular lymphoma, most frequently occurring as vitreoretinal lymphoma or, less frequently, as uveal lymphoma, and rarely as iridal lymphoma. Fifteen percent to 25% of patients with PCNSL develop intraocular lymphoma.

Ocular symptoms are described as slowly progressive, minor, disabling blurred vision, floaters, or decreased visual acuity, varying from normal to hand motion. Fundus findings include vitreous opacities, vitritis, subretinal infiltration, and retinal detachment.

In patients with PCNSL with ocular involvement, the duration of symptoms before diagnosis ranges from less than 1 to 48 months, with a mean duration ranging from 3 to 6 months. Delay in diagnosis of intraocular lymphoma is primarily caused by the disorder’s insidious onset. Lymphomatous ONI, in contrast, is characterized by subacute onset during a few days with severe visual loss, associated with normal ophthalmologic examination findings and optic nerve contrast enhancement with or without optic nerve thickening on MRI.

The diagnosis of lymphomatous infiltration of the optic nerve is relatively easy when concomitant parenchymal CNS lesions and/or lymphomatous meningitis are found. Establishing this diagnosis is more difficult in isolated lymphomatous ONI, especially if it is the initial presentation of lymphoma. This condition may easily be misdiagnosed, as in our series, in favor of more frequent conditions that display similar symptoms and signs. The differential diagnosis of optic neuropathy is broad, including optic neuritis (infectious and idiopathic), neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders, other autoimmune disorders, inflammatory pseudotumors (including IgG4-related disease), ischemic optic neuropathy (arteritic and nonarteritic), other compressive and infiltrative optic neuropathies (such as optic nerve gliomas, optic nerve sheath meningiomas, and optic nerve and orbital metastases), paraneoplastic optic neuropathy, inherited disorders (eg, Leber hereditary optic neuropathy), and toxic, nutritional, and metabolic optic neuropathies.

Accurate clinical and paraclinical workup should therefore include comprehensive laboratory and neuroimaging studies. Orbital MRI, systematically complemented by brain MRI, should focus on both optic nerves and include high-resolution fat-suppressed sequences. We suggest adding diffusion-weighted imaging with apparent diffusion coefficient mapping, although further evaluation is required regarding specificity.

Subacute onset of severe visual impairment, the absence of signs of vitreoretinal lymphoma, and the presence of contrast-enhancing lesions of the optic nerve will help guide the diagnosis. If no final diagnosis can be established by means of less invasive methods and in the absence of other lesions, optic nerve biopsy as the last diagnostic option may be inevitable.

Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for PCNSL might be helpful for diagnosis and differentiation, particularly from inflammatory diseases. Recently, several biomarkers have been described, including miRNAs, interleukin 10, CXC chemokine ligand 13, and circulating U2 small nuclear RNA fragments. The presence of miRNAs in the CSF of 3 of our patients was useful for the diagnosis.

Functional visual outcome was poor in this series, with permanent severe visual acuity loss or blindness in most of our patients, even in patients with a complete MRI response to treatment. We presume that infiltration with secondary compression and ischemic lesions adversely affected the outcome. In both patients with partial visual recovery, a short time elapsed from the onset of symptoms to the beginning of treatment, and both achieved a complete response as seen radiologically on follow-up MRI. We therefore assume that early diagnosis, leading to early treatment, improves the visual prognosis. This finding emphasizes the importance of prompt exploration of optic nerve dysfunction in this context. In addition, after ONI has been diagnosed, we recommend immediate initiation of intravenous high-dose corticosteroid therapy, followed by chemotherapy suitable for PCNSL. Nevertheless, lymphomatous ONI remained associated with a high mortality in our cohort, similar to that seen in patients with other locations of relapsing PCNSL.

Limitations

Relevant limitations of our study include the small number of patients in the examined cohort and the retrospective nature. The incidence of lymphomatous ONI might be underestimated because such a rare condition might be missed even in specialized centers.

Conclusions

Although intraocular involvement is frequent in PCNSL and clinically marked by slowly progressive visual deterioration during several months, lymphomatous ONI is rare and characterized by rapidly progressive severe visual impairment with optic nerve contrast enhancement on imaging. In the absence of cerebral lesions or lymphomatous meningitis, establishing the diagnosis can be difficult, especially if ONI is the initial presentation of PCNSL, because the differential diagnosis is broad. Optic nerve functional outcome is poor, even in patients with a visible imaging response to chemotherapy. Rapid treatment might improve the clinical outcome in these patients.

eTable. Clinical and Radiological Presentation and Treatment of ONI of PCNSL (n = 7)

References

- 1.Grimm SA, McCannel CA, Omuro AM, et al. . Primary CNS lymphoma with intraocular involvement: International PCNSL Collaborative Group Report. Neurology. 2008;71(17):1355-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baryla J, Allen LH, Kwan K, Ong M, Sheidow T. Choroidal lymphoma with orbital and optic nerve extension: case and review of literature. Can J Ophthalmol. 2012;47(1):79-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JL, Mendoza PR, Rashid A, Hayek B, Grossniklaus HE. Optic nerve lymphoma: report of two cases and review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2015;60(2):153-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zelefsky JR, Revercomb CH, Lantos G, Warren FA. Isolated lymphoma of the anterior visual pathway diagnosed by optic nerve biopsy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;28(1):36-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gill MK, Jampol LM. Variations in the presentation of primary intraocular lymphoma: case reports and a review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;45(6):463-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kansu T, Orr LS, Savino PJ, Schatz NJ, Corbett JJ. Optic neuropathy as initial manifestation of lymphoreticular diseases: a report of 5 cases In: Smith JL, ed. Neuro-ophthalmology Focus 1980. New York, NY: Masson Publishing USA Inc; 1979:125-136. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tatsugawa M, Noma H, Mimura T, Funatsu H. Unusual orbital lymphoma undetectable by magnetic resonance imaging: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim UR, Shah AD, Arora V, Solanki U. Isolated optic nerve infiltration in systemic lymphoma: a case report and review of literature. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26(4):291-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sudhakar P, Rodriguez FR, Trobe JD. MRI restricted diffusion in lymphomatous optic neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2011;31(4):306-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrey LE, Batchelor TT, Ferreri AJ, et al. ; International Primary CNS Lymphoma Collaborative Group . Report of an international workshop to standardize baseline evaluation and response criteria for primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5034-5043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baraniskin A, Kuhnhenn J, Schlegel U, et al. . Identification of microRNAs in the cerebrospinal fluid as marker for primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system. Blood. 2011;117(11):3140-3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi JY, Kafkala C, Foster CS. Primary intraocular lymphoma: a review. Semin Ophthalmol. 2006;21(3):125-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong JT, Chae JB, Lee JY, Kim JG, Yoon YH. Ocular involvement in patients with primary CNS lymphoma. J Neurooncol. 2011;102(1):139-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan CC, Rubenstein JL, Coupland SE, et al. . Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: a report from an International Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma Collaborative Group symposium. Oncologist. 2011;16(11):1589-1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biousse V, Newman NJ. Diagnosis and clinical features of common optic neuropathies. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(13):1355-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akansel G, Hendrix L, Erickson BA, et al. . MRI patterns in orbital malignant lymphoma and atypical lymphocytic infiltrates. Eur J Radiol. 2005;53(2):175-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dayan MR, Elston JS, McDonald B. Bilateral lymphomatous optic neuropathy diagnosed on optic nerve biopsy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(10):1455-1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behbehani RS, Vacarezza N, Sergott RC, Bilyk JR, Hochberg F, Savino PJ. Isolated optic nerve lymphoma diagnosed by optic nerve biopsy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(6):1128-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sasayama T, Nakamizo S, Nishihara M, et al. . Cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-10 is a potentially useful biomarker in immunocompetent primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL). Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(3):368-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubenstein JL, Wong VS, Kadoch C, et al. . CXCL13 plus interleukin 10 is highly specific for the diagnosis of CNS lymphoma. Blood. 2013;121(23):4740-4748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen-Them L, Costopoulos M, Tanguy ML, et al. ; French LOC Network for CNS Lymphoma . The CSF IL-10 concentration is an effective diagnostic marker in immunocompetent primary CNS lymphoma and a potential prognostic biomarker in treatment-responsive patients. Eur J Cancer. 2016;61(5):69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baraniskin A, Zaslavska E, Nöpel-Dünnebacke S, et al. . Circulating U2 small nuclear RNA fragments as a novel diagnostic biomarker for primary central nervous system lymphoma. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(3):361-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jahnke K, Thiel E, Martus P, et al. ; German Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma Study Group . Relapse of primary central nervous system lymphoma: clinical features, outcome and prognostic factors. J Neurooncol. 2006;80(2):159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langner-Lemercier S, Houillier C, Soussain C, et al. . Primary CNS lymphoma at first relapse/progression: analysis of 256 patients from the French LOC Network. Neuro-oncol. 2016;18(9):1297-1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Clinical and Radiological Presentation and Treatment of ONI of PCNSL (n = 7)