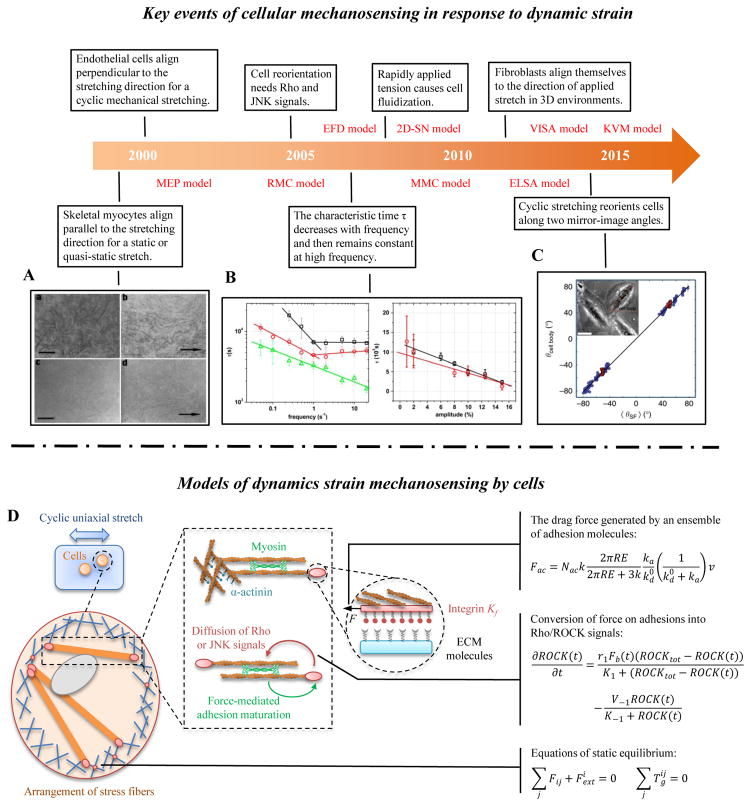

Figure 2. Cellular mechanosensing in response to dynamic strain.

(A) Under conditions simulating mammalian long bone growth (e.g., a static or quasi-static stretch), cultured myocytes respond to mechanical forces by lengthening and orienting along the direction of stretch [82]. (B) Many tissue cells (e.g., fibroblasts and endothelial cells) prefer to align perpendicular to the direction of applied cyclic strain, especially at high frequency and larger stretching magnitude [83]. (C) Cells can reorient to a uniform angle in response to cyclic stretching of the underlying substrate [84]. (D) A mechanical model of SFs, showing adhesion complexes, myosin motors and actin filaments. Myosin motors generate force between antiparallel actin filament bundles, one of which is anchored to the matrix by adhesion complexes. Proteins in adhesion and actin filaments system are drawn as masses on springs in order to indicate how they function in the model.