Abstract

Salmonella Enteritidis (SE), Salmonella Typhimurium (ST), and Salmonella Heidelberg (SH) have been responsible for numerous outbreaks associated with the consumption of poultry meat and eggs. Salmonella colonization in chicken is characterized by initial attachment to the cecal epithelial cells (CEC) followed by dissemination to the liver, spleen, and oviduct. Since cecal colonization is critical to Salmonella transmission along the food chain continuum, reducing this intestinal association could potentially decrease poultry meat and egg contamination. Hence, this study investigated the efficacy of Lactobacillus delbreuckii sub species bulgaricus (NRRL B548; LD), Lactobacillus paracasei (DUP-13076; LP), and Lactobacillus rhamnosus (NRRL B442; LR) in reducing SE, ST, and SH colonization in CEC and survival in chicken macrophages. Additionally, their effect on expression of Salmonella virulence genes essential for cecal colonization and survival in macrophages was evaluated. All three probiotics significantly reduced Salmonella adhesion and invasion in CEC and survival in chicken macrophages (p < 0.05). Further, the probiotic treatment led to a significant reduction in Salmonella virulence gene expression (p < 0.05). Results of the study indicate that LD, LP, and LR could potentially be used to control SE, ST, and SH colonization in chicken. However, these observations warrant further in vivo validation.

Keywords: Salmonella, lactic acid bacteria, probiotic, cecal colonization, macrophages, gene expression, in vitro

1. Introduction

Salmonella enterica, a Gram-negative foodborne pathogen, is one of the leading causes of foodborne gastroenteritis in humans. Globally, it is estimated that foodborne Salmonellosis accounts for 93.8 million cases and 155,000 deaths each year [1]. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that Salmonella is responsible for 1 million illnesses, and 380 deaths annually [2]. Although different Salmonella serovars have been implicated in these foodborne outbreaks, a limited number of them are responsible for most human infections [3,4]. In the US, during 2007–2011, five of the most common serovars caused 61% of all Salmonella-related outbreaks. Serovar Enteritidis was the most frequently isolated (27%) followed by Typhimurium (14%), Newport (10%), Heidelberg (7%), and Montevideo (3%) [5].

While various food sources, including pork, beef, and fresh produce, have been implicated in Salmonella outbreaks, these infections are often associated with the consumption of raw or undercooked poultry products [3,6]. In fact more than 70% of human Salmonellosis in the US are attributed to the consumption of contaminated poultry meat and eggs [5]. Further investigations into the serovar diversity within each commodity group revealed that the egg- and chicken-associated outbreaks were predominantly caused by S. Enteritidis (SE, 83%) and S. Heidelberg (SH; 9%), and SE (28%), S. Typhimurium (ST; 23%), and SH (13%), respectively [4]. This link between zoonotic foodborne infection and poultry products is concerning given the tremendous increase in the demand for poultry meat and eggs. It is estimated that people consume approximately 250 eggs per year and that poultry meat constitutes almost 50% of the annual per capita consumption of meat in the US [6,7]. Therefore, the microbiological safety of poultry products is a major concern from public health and economic perspectives [8].

Poultry populations, particularly chickens are frequently colonized with Salmonella by horizontal and vertical transmission [3,9,10]. On the farm, the contamination cycle begins with the infection of the animal and proceeds by shedding of pathogens in the feces which, in turn, contaminates the environment and leads to new infections or reinfection of animals [3,6]. In chickens, within a few hours of oral infection, Salmonella can colonize and invade the ceca, reaching other internal organs like the liver and spleen [10,11]. In laying hens, systemic dissemination includes the colonization and invasion of the reproductive tissues thereby resulting in direct contamination of eggs [10,12]. Therefore, intestinal colonization is central to Salmonella entry into the food chain continuum either via contaminated meat and/or eggs [13]. Consequently, pre-harvest control measures aiming at reducing Salmonella colonization are critical to prevent pathogen contamination on poultry products and promote public health [14,15,16].

Various strategies including sanitary barriers, acidification of the chicken environment using short- and medium-chain fatty acids, vaccination, bacteriophages, antimicrobial peptides, and probiotics, have been investigated for their ability to reduce Salmonella in chicken [17]. Among the antimicrobial approaches mentioned above, probiotics including lactic acid bacteria (LAB) have shown promise in the control of poultry pathogens [18]. Probiotics are defined as “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host” [19]. Probiotics reduce survival and colonization of enteric pathogens through several mechanisms including improved intestinal barrier function, competitive exclusion, production of antimicrobial metabolites, and the modulation of the structure and function of intestinal epithelium [20]. In this regard, the use of LAB has been suggested as an effective measure to control salmonellosis in chicken [21]. Additionally, in-feed supplementation of probiotic LAB have demonstrated growth-promoting abilities associated with an increase in growth and performance in chicken [22]. Moreover, these studies have shown that supplementation of probiotics to chicken may reduce dysbiosis and help develop natural resistance to pathogens [23,24]. In light of the need for effective alternatives to control Salmonella in chicken, our study investigated the probiotic potential of select LAB to inhibit the attachment to and invasion of chicken primary cecal epithelial cells (CEC) by SE, ST, and SH in vitro. Additionally, the effect of LAB on the expression of virulence genes essential for Salmonella colonization in the cecum was studied.

2. Results and Discussion

While there are several opportunities for transfer of Salmonella to poultry meat and eggs, cecal colonization in chickens is central to the direct transmission of the pathogen along the food chain continuum [25,26,27]. Therefore, reducing cecal carriage in chicken would help control fecal shedding and eventual contamination of poultry carcass and eggs. Towards this, our research focusses on the development of probiotic-based prophylactics to control Salmonella in chicken. As a first step, in the current study, we determined the efficacy of L. rhamnosus NRRL B442 (LR), L. paracasei DUP-13076 (LP) and L. delbrueckii sub sp. bulgaricus NRRL B548 (LD) to inhibit Salmonella colonization and dissemination in vitro. To date, no studies have investigated the probiotic potential of LR, LP, and LD in controlling Salmonella colonization.

2.1. Sub-Inhibitory Concentrations (SICs) of LAB Cell-Free Supernatant (CFSN)

The highest concentration of CFSN which did not inhibit Salmonella growth was determined to be the SIC. Of the different CFSN concentrations tested, 7.5% CFSN was identified to be the SIC for LP, LD, and LR. The average initial Salmonella (SE/ST/SH) population in the control and CFSN-treated samples was ~6.3 log10 CFU/mL. Following incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, ~8.2 log10 CFU/mL of Salmonella spp. was recovered from all samples, irrespective of control and CFSN treatment. This confirmed that the CFSN concentration used in the assay (7.5%) was not inhibitory to the bacteria. Since the LAB tested were found to be equally effective against different isolates within each Salmonella enterica serovar, namely SE isolates (SE-21 and SE-90), ST isolates (ST-43 and ST-J380) and SH isolates (SH-1 and SH-V6FA), for any of the tested parameters, only results observed with SE-90, ST-43, and SH-V6FA are provided in the manuscript, unless mentioned otherwise.

2.2. Motility Assay

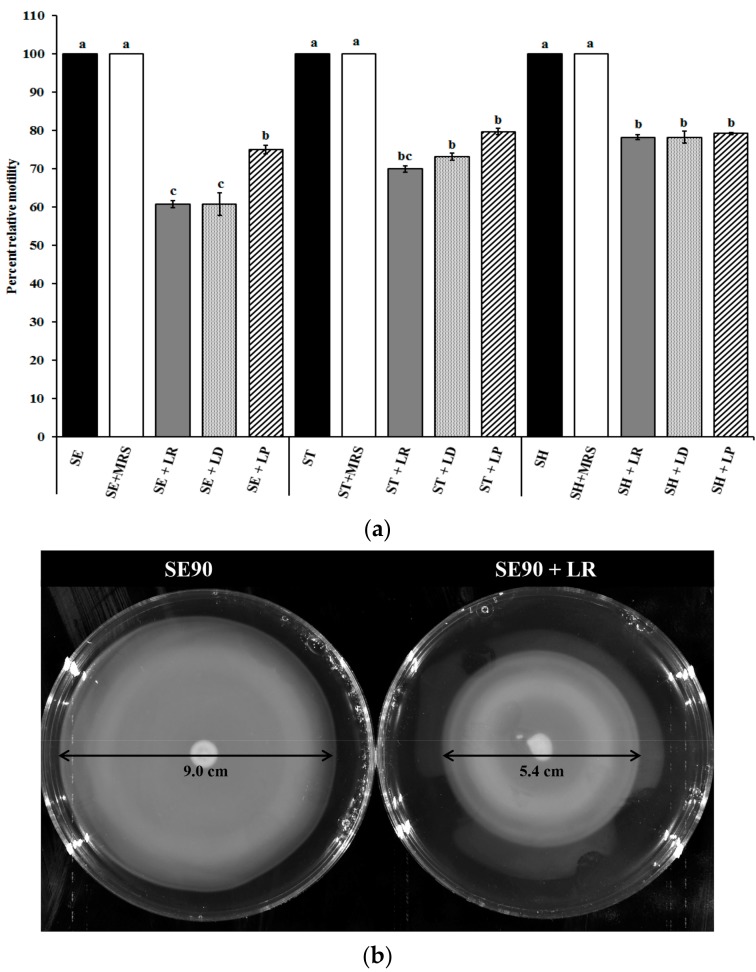

Since bacterial motility is a key attribute that enables intestinal colonization by the pathogen [28], we evaluated the ability of different LAB cultures to inhibit Salmonella motility. Briefly, SE, ST, and SH were grown in the presence of SICs of LAB CFSN (7.5%), and the motility assay was performed. It can be seen from Figure 1 that LP, LR, and LD significantly (p < 0.05) reduced Salmonella motility, by 20–40% compared to the control (Figure 1a). Treatment with LR reduced SE, ST, and SH motility by 40%, 30%, and 20%, respectively, compared to the control. Similarly, LD reduced ST motility by ~25%, while LP resulted in only ~15% reduction in ST motility. In the case of SH, LR, LD, and LP were found to be equally effective in reducing pathogen motility by 20%. Figure 1b is a pictorial representation of the observed reduction in SE motility following treatment with LR CFSN.

Figure 1.

(a) Effect of sub-inhibitory concentrations of LAB supernatants on Salmonella motility. Data are presented as means ± SEM. a−c Different superscripts indicate the significant difference in LS-means (p < 0.05), MRS-de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe broth, SE: S. Enteritidis 90; ST: S. Typhimurium DT104 43; SH: S. Heidelberg V6FA; LR: L. rhamnosus NRRL B442; LP: L. paracasei DUP-13076; LD: L. delbreuckii bulgaricus NRRL B548; (b) Representative image of the motility assay performed with Salmonella Enteritidis 90 (SE90) treated with and without SIC of L. rhamnosus NRRL B442 (LR) supernatant; (c) Effect of sub-inhibitory concentrations of LAB supernatants on the expression of motility genes in Salmonella. Data are presented as means ± SEM; (d) Representative TEM images of Salmonella Enteritidis 90 (SE90) treated with and without SICs of L. rhamnosus NRRL B442 (LR) supernatant. Salmonella, Arrows indicate the presence and absence of flagella.

As can be seen from the Figure 1b, treatment with LR CFSN reduced the zone of motility to 5.4 ± 0.16 cm compared to 9.0 ± 0.08 cm in the untreated control group (~40% reduction). This reduction in motility could be either due to a defect in structure or function of the Salmonella motility apparatus [29,30,31]. To understand the underlying molecular mechanism, real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed to evaluate the differential expression of genes associated with motility in Salmonella, namely, flgG and motA. While MotA is important in providing the motive force to the flagella, FlgG is critical to the formation of the flagellar rod [32,33]. Results of this assay revealed that LR, LD, and LP significantly reduced motA and flgG expression in SE, ST, and SH compared to the untreated control (p < 0.05; Figure 1c). For example, LR reduced motA expression by ~7–10 fold in all serovars, and flgG expression by 2-, 30-, and 40-fold in SE, ST, and SH, respectively. In order to detect any structural changes in the flagellar apparatus induced by LAB treatment, transmission electron microscopy was performed. As can be seen from Figure 1d, treatment of SE with LR CFSN reduced the flagellar presence on the cell surface when compared to the untreated control. These results are in conjunction with previous studies that have demonstrated that reduced expression of genes associated with motility will impair the formation of the motility apparatus [34].

2.3. Inhibition of Salmonella Adhesion and Invasion in Cecal Epithelial Cells (CEC)

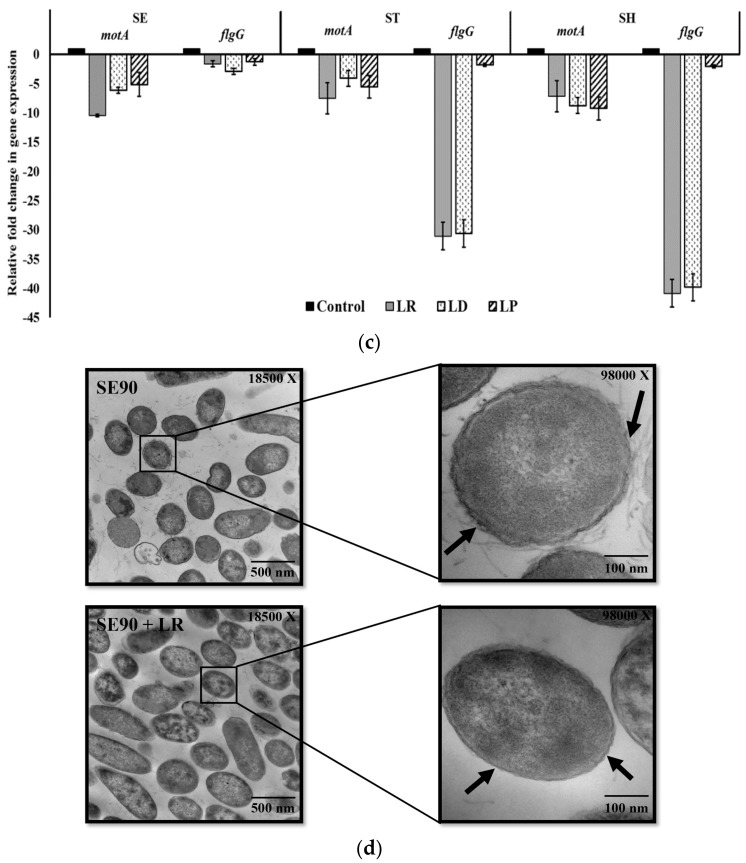

Since no established chicken cecal epithelial cell lines (CEC) are commercially available, we isolated primary epithelial cells from chicken ceca. The primary CEC have been previously utilized to study Salmonella colonization and interaction with the chicken cecal epithelium [35]. Epithelial characterization of the isolated CEC was confirmed by selectively staining for cytokeratin using FITC labeled anti-cytokeratin antibodies (Figure 2) [35]. Furthermore, to validate the epithelial localization of cytokeratin, immunostaining of Budgerigar abdominal tumor cells (BATC, permanent avian intestinal epithelial cell line) was performed as the positive control.

Figure 2.

Confirmation of epithelial characteristics of CEC using immunofluorescence.

Following validation, the monolayer was utilized in the adhesion and invasion assays. Before proceeding with the assays, LAB candidates (LD, LP, and LR) were screened for their ability to adhere to the CEC. Adhesion to the intestinal epithelium is a critical probiotic attribute that facilitates competitive exclusion and antagonism against pathogens [36]. The select LAB cultures (7 log10 CFU/mL) were added to the CEC monolayer and incubated for 2 h. Following incubation, enumeration of the adhered LAB was performed. Approximately 6 log10 CFU/mL of adhered LAB was recovered with all the isolates tested. In addition to adhesion, the absence of any adverse effects on the CEC due to LAB pre-exposure was verified using the trypan blue assay. This assay revealed that LD/LP/LR did not exert any adverse effects on CEC viability, and no cytotoxicity was observed (data not shown). Further, there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) between the adhesion and invasion capabilities of the different Salmonella isolates used in this study (data not shown).

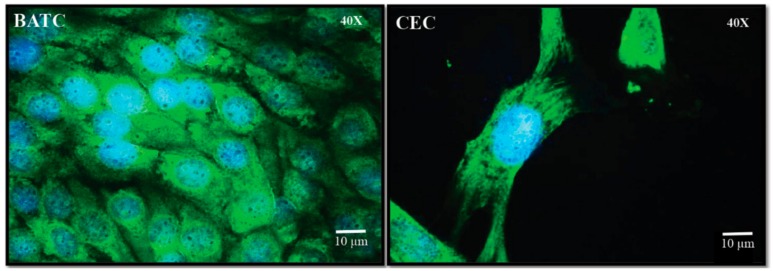

For the Salmonella adhesion inhibition assay, CEC monolayers were pre-exposed to the different LAB cultures (LD/LP/LR) for 24 h followed by Salmonella infection. Figure 3a depicts the results of the Salmonella adhesion assay. The results of this assay demonstrate that LD, LP, and LR were effective in significantly (p < 0.05) inhibiting SE, ST, and SH adhesion to primary CECs by ~60–95% when compared with the control (Figure 3a). In addition to inhibiting adhesion, LR, LD, and LP significantly reduced Salmonella invasion into CEC by ~60–99% (Figure 3b). Although all three LAB cultures reduced Salmonella adhesion and invasion in CEC, this inhibitory effect was found to be species-specific with respect to the LAB cultures tested. For example, while LR and LD were equally effective in reducing SE invasion by >90%, exposure to LP only resulted in 60% inhibition of pathogen internalization (Figure 3b). Furthermore, the LAB mediated anti-Salmonella activity was also found to vary significantly (p < 0.05) with the Salmonella serovar with differences observed between SE, ST, and SH (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(a) Effect of LAB pre-treatment on Salmonella adhesion to primary cecal epithelial cells. Salmonella; a−e Different superscripts indicate the significant difference in LS-means (p < 0.05); (b) Effect of LAB pre-treatment on Salmonella invasion in primary cecal epithelial cells. Salmonella; Data are represented as means ± SEM; a−f Different superscripts indicate the significant difference in LS-means (p < 0.05).

To understand the underlying mechanism that mediates LAB-associated attenuation of Salmonella colonization, we performed RT-qPCR on Salmonella virulence genes. These include genes for adhesion and invasion, namely, sopB and invH [37,38]; Type III secretion system (T3SS) effectors, namely, sipA and sipB [38]; and Salmonella pathogenicity island-I (SPI-I) encoded transcriptional regulators hilA and hilD [39]. Salmonella outer protein B (encoded by sopB) is a lipid phosphatase that has been demonstrated to be critical for enteropathogenicity in a bovine model [40,41]. SPI-1 of Salmonella encodes two transcriptional regulators, HilA, and InvH; HilA regulates expression of T3SS machinery, and InvH is required for proper assembly of T3SS-1. Moreover, HilD is known to modulate the expression of hilA [42,43,44]. Additionally, Shah and others [45] demonstrated that hilD and invH mutants were associated with attenuated virulence in vivo. Additionally, deletion of invH in Salmonella resulted in a reduced injection of T3SS effector proteins into the host cells [46]. Hence, downregulation of these genes could lead to reduced adhesion and invasion of Salmonella into the host cells. Results of our RT-qPCR assays demonstrate that following LAB treatment, all the genes tested showed a significant reduction in their expression (p < 0.05) when compared to the control (Table 1). Genes critical to adhesion including invH, hilA, and hilD, were downregulated by ~2–12 fold by LP, LD, and LR in all Salmonella serovars. Similarly, a significant reduction in the expression sipA, sipB, and sopB was also observed with SE, ST, and SH. These results corroborate with the cell association assays where exposure to LAB significantly reduced adhesion and invasion of SE, ST, and SH in CECs (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Effect of sub-inhibitory concentrations of LAB supernatants on the expression of virulence genes in Salmonella Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, and S. Heidelberg.

| Treatments | invH | hilA | hilD | sipA | sipB | sopB | spvB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE Ctrl | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a |

| SE + LR | –1.85 ± 0.08 b | –4.58 ± 1.13 b–d | –2.90 ± 0.15 b,c | –5.01 ± 0.76 b–d | –18.69 ± 0.46 g | –6.67 ± 1.39 b–d | –8.17± 1.55 b–d |

| SE + LD | –2.66± 0.14 b,c | –3.54 ± 0.71 b,c | –2.20 ± 0.10 b | –1.87 ± 0.15 b | –1.91 ± 0.19 b | –2.93 ± 0.44 b,c | –17.27 ± 3.26 f,g |

| SE + LP | –4.07± 0.84 a,b | –4.07 ± 0.38 b–d | –2.81 ± 0.28 b,c | –11.19± 0.36 d,e | –27.19 ± 0.66 i | –15.70± 0.54 e–g | –25.46 ± 0.91 h,i |

| ST Ctrl | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a |

| ST + LR | –11.31± 0.22 d,e | –2.31 ± 1.04 b,c | –2.74 ± 0.9 b,c | –2.89 ± 1.12 b | –19.35 ± 0.27 g | –3.55 ± 0.51 b,c | –7.16 ± 0.88 b–d |

| ST + LD | –3.98 ± 1.2 a,b | –3.98 ± 0.93 b–d | –2.09 ± 0.66 b | –1.37 ± 0.28 b | –1.78 ± 0.28 b | –1.89 ± 0.28 b | –10.40 ± 1.17 d,e |

| ST + LP | –3.05± 0.77 b,c | –1.45 ± 0.56 b | –2.72 ± 0.55 b,c | –12.13± 1.65 d–f | –28.92 ± 1.53 i | –6.00 ± 1.93 b–d | –25.46 ± 4.8 h,i |

| SH Ctrl | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a | 1 a |

| SH + LR | –3.12 ± 0.64 b,c | –2.00 ± 0.2 a | –2.54 ± 0.6 b,c | –3.29 ± 0.16 b,c | –17.21 ± 3.45 f,g | –3.22 ± 0.33 b,c | –19.97 ± 0.22 g,h |

| SH+ LD | –4.42 ± 1.09 a,b | –5.76 ± 0.55 b–d | –2.04 ± 0.63 b | –1.67 ± 0.17 b | –3.29 ± 0.75 b,c | –2.22 ± 0.23 b | –19.61 ± 0.53 g,h |

| SH + LP | –5.45 ± 2.53 a,b | –12.11± 0.55 d–f | –2.68 ± 0.22 b,c | –10.53 ± 0.99 d,e | –27.96 ± 1.99 i | –4.69 ± 0.67 b–d | –30.86 ± 1.41 i |

a−i Different superscripts indicate the significant difference in LS-means (p < 0.05).

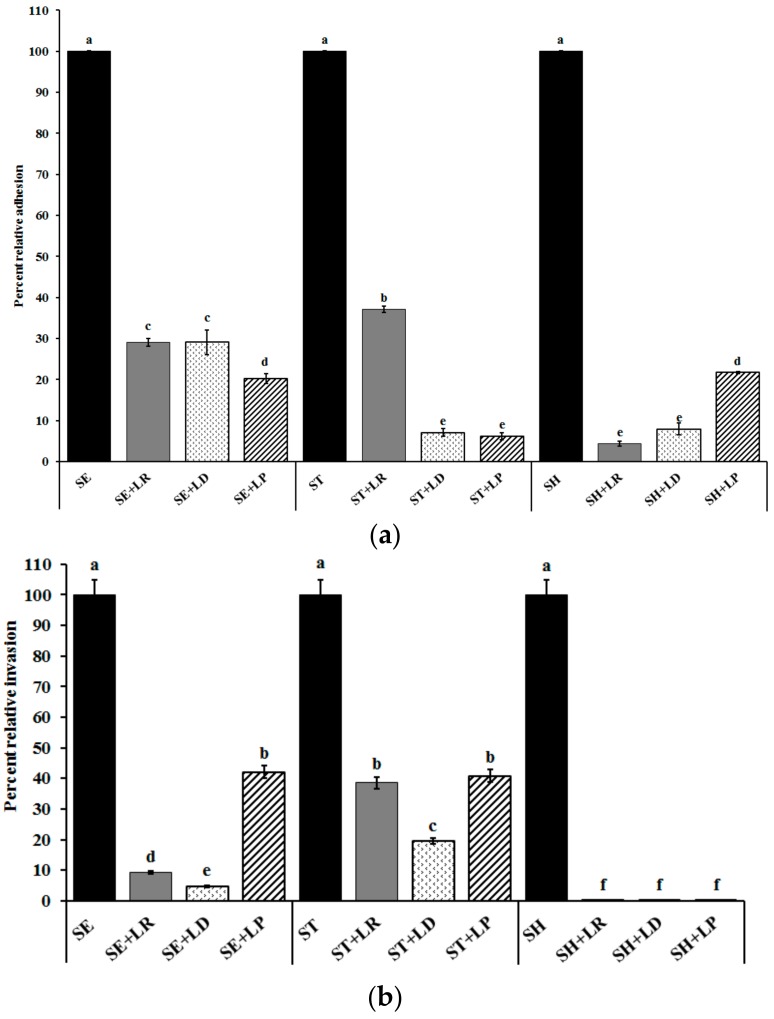

2.4. Inhibition of Salmonella Invasion and Survival in Chicken Macrophage

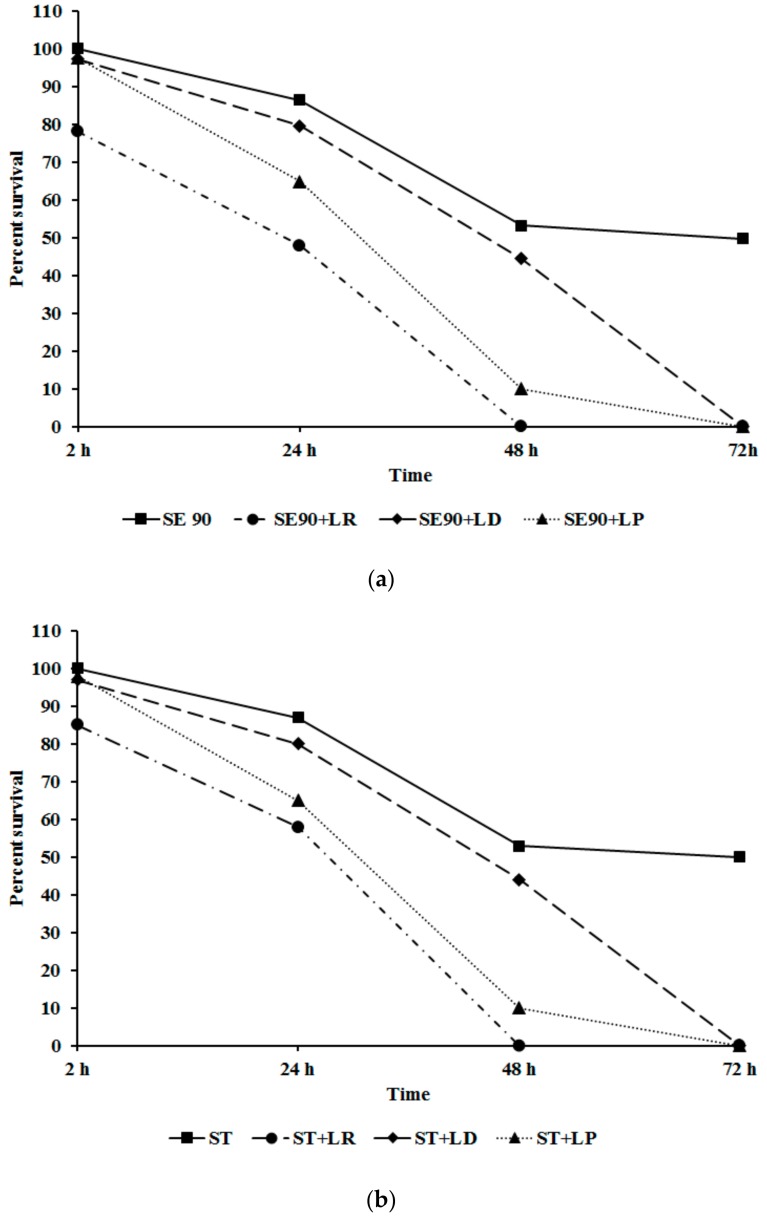

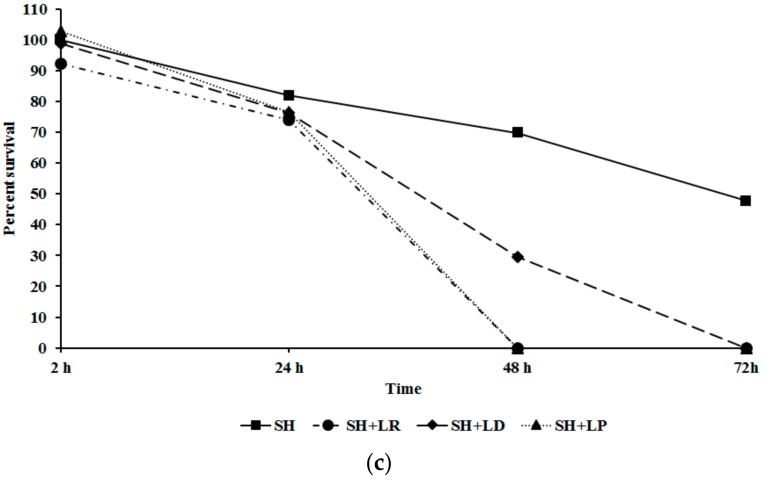

Following intestinal colonization, Salmonella is disseminated to other organs including the liver, spleen, and oviduct by macrophages [12,47]. Hence, we investigated the ability of LAB to inhibit Salmonella invasion and survival in chicken macrophages. It can be seen from Figure 4 that the different LAB CFSNs at their SICs (7.5%) were effective in significantly reducing Salmonella invasion and survival in chicken macrophages (p < 0.05). For example, LR significantly reduced Salmonella survival by 50%, 29%, and 25% by 24 h with SE, ST, and SH, respectively, with complete inhibition observed at the end of the study (Figure 4) A similar trend was observed with LP and LD in the case of SE and ST, however, with SH, treatment with LR and LP completely inhibited its intracellular survival by 48 h (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(a) Effect of LAB pre-treatment on Salmonella Enteritidis 90 invasion and survival in chicken macrophages. Data are represented as means ± SEM; (b) Effect of LAB pre-treatment on Salmonella Typhimurium DT 104 43 invasion and survival in chicken macrophages. Data are represented as means ± SEM; (c) Effect of LAB pre-treatment on Salmonella Heidelberg V6FA invasion and survival in chicken macrophages. Data are represented as means ± SEM.

As previously discussed, following macrophage invasion, Salmonella successfully spreads to extra-intestinal tissues resulting in systemic dissemination. Effector proteins of SPI-2 T3SS, such as SpvB, are critical to the survival of Salmonella in macrophages [48]. In addition to SpvB, SPI-1 T3SS effectors, SipA modulates host actin cytoskeleton, and SopB protects the Salmonella-infected epithelial cells from phagocytosis [49]. About 2–15 fold reduction in sipA and sopB expression was noticed in treatment groups (Table 1). SipB of SPI-1 T3SS has been demonstrated to bind to caspase 1 leading to bovine and murine macrophage cell death, thereby promoting Salmonella survival and escape from the phagocytic cells [41]. Our study has demonstrated that LP, LR, and LD reduced SipB and SpvB expression by ~2 to 30-fold thereby preventing Salmonella escape and reducing its survival in macrophages. Further, the reduced expression of sipB could lead to the observed reduction in the intracellular survival of Salmonella in HTC (Figure 4). Results from the current study demonstrate that application of LP, LD, and LR significantly impaired the pathogen’s ability to invade and survive within chicken macrophages by modulating virulence gene expression in the SPI-1 and SPI-II T3SS locus.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Bacterial Isolates and Growth Conditions

LAB used in the study (L. delbreuckii sub spp. bulgaricus NRRL B548 and L. rhamnosus NRRL B442) were obtained from USDA Agriculture Research Service (NRRL) Culture Collection (Peoria, IL, USA). L. paracasei DUP-13076 was kindly provided by A. K. Bhunia, Molecular Food Microbiology Laboratory, Food Science Department, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA. Two isolates each of Salmonella Enteritidis (SE; SE-21and SE-90) and multidrug resistant S. Typhimurium DT104 (ST; ST-43 and ST-J380), and S. Heidelberg (SH; SH-V6FA and SH-1) were used in the study. All bacteriological media used in the study were procured from Difco (Difco Becton, MD, USA). LAB cultures were grown in de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe broth (MRS) and Salmonella in Tryptic Soy broth (TSB) at 37 °C overnight. After incubation, the cultures were centrifuged (3000× g, 12 min, 4 °C), and washed twice in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.0), separately. The pellet was then resuspended in PBS and used as the inoculum. Bacterial counts in the LAB and Salmonella cultures were confirmed following serial dilution and plating on MRS agar and tryptic soy agar (TSA), respectively. Since our preliminary experiments revealed that the LAB cultures were not adept to grow on TSA, and no significant difference (p > 0.05) was observed between Salmonella populations on TSA and xylose lysine desoxycholate agar, routine pathogen enumeration was performed using TSA.

3.2. Estimation of Sub-Inhibitory Concentration of LAB Cell-Free Supernatant

To obtain LAB CFSN, overnight cultures of LD/LP/LR were centrifuged (3000× g, 15 min, 4 °C) and the supernatant was filtered using 0.22 µm syringe filter [50]. The SIC of LAB supernatants was estimated as previously described [51,52]. Approximately 6 log10 CFU/mL of Salmonella was inoculated into 10 mL of TSB supplemented with different concentrations of CFSN (0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, 5%, 7.5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Following incubation, the surviving Salmonella population was enumerated by dilution and plating on TSA. The highest concentration of CFSN which did not inhibit Salmonella (SE, ST, SH) growth was determined to be the SIC.

3.3. Motility Assay

SE, ST, and SH isolates were cultured in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) in the presence or absence of SICs of different LAB CFSN or MRS (control) at 37 °C for 14 h. Ten microliters of the culture (8 log10 CFU/mL) was placed in the center of an agar plate (TSA containing 0.3% agar) and incubated for 8 h at 37 °C and zone of motility was measured [53,54]. The assay for each LAB CFSN and Salmonella strain was run in duplicate, and the entire experiment replicated three times.

3.4. Isolation of Chicken Primary CEC

Primary cecal cells were isolated according to a published protocol [35]. Briefly, ceca from healthy birds (n = 6) were collected in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS, HyClone, Logan, UT) containing 1% PenStrep, and cecal contents were removed. Ceca were then cut into small pieces of ~3 mm2 and digested using a digestion media containing Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM, HyClone), collagenase type XI, dispase I, fetal bovine serum and PenStrep (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 2 h at 37 °C. The digested suspension was filtered (180 µm pore size), resuspended in 4% d-sorbitol solution, and centrifuged for 5 min at 500× g. The pellet was resuspended in 6% d-sorbitol, filtered (150 µm pore size) and centrifuged for 5 min at 500× g. The procedure was repeated until the supernatant was clear. The pellet was then resuspended in DMEM containing 2.5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 0.1% insulin, 0.5% transferrin, 0.007% hydrocortisone, 0.1% fibronectin, and 1% PenStrep and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 to form a confluent monolayer. The epithelial characteristics of the cells in the monolayer were confirmed by staining for cytokeratin (cytokeratin pan antibody (AE1/AE3), 1/2000 dilution; Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) as described by Van Immerseel et al. [35]. Prior to validating the epithelial nature of the isolated CEC, cytokeratin localization in epithelial cells was confirmed by staining BATC [51]. This cell line has been previously utilized to study Salmonella pathogenesis in avian species [55,56,57,58].

3.5. Inhibition of Salmonella Adhesion to CEC

LAB cultures (LD/LP/LR) were washed and resuspended in DMEM with 10% FBS (~8 log10 CFU/mL). CEC were seeded on a 24-well tissue culture plate at ~105 cells per well, and inoculated with ~7.0 log10 CFU/well of each LAB strain separately. The tissue culture trays were centrifuged at 600× g for 5 min, and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator. The cells were then washed three times with PBS and infected with ~6.0 log10 CFU/well of each SE, ST, or SH isolates separately (MOI 10). The tissue culture trays were centrifuged at 600× g for 5 min, and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator for 2 h [59]. The wells were then washed three times with PBS, and the CEC were lysed using 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 10 min to release the adherent and internalized Salmonella. The cell homogenates were diluted ten-fold in PBS and plated on TSA to enumerate the CEC associated Salmonella population [60]. In addition to Salmonella enumeration, LAB adherence to CEC was also estimated following dilution and plating on MRS agar. Duplicate wells were used for each treatment and control, and the experiment was repeated three times.

3.6. Inhibition of Salmonella Invasion in CEC

For the internalization assay, CEC monolayers were pre-exposed to the different LAB cultures and infected with SE, ST, or SH as described previously. Following infection for 2 h, monolayers were washed three times with DMEM and incubated in whole media containing 100 µg/mL gentamicin for 1 h to kill all the adhered (extra cellular) bacteria. Internalized Salmonella were then enumerated after triton lysis and plating on TSA [54,60]. The invasion assay for each Salmonella strain was run in duplicate and replicated three times.

3.7. Inhibition of Salmonella Invasion and Survival in HTC

Chicken monocyte cell line (HTC; [61]) was cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 Medium (HyClone) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 to form confluent monolayers. The cells were activated and plated as described previously [12,61]. Following activation, inhibition of Salmonella invasion and survival in macrophages was assayed as previously described [12,54,61]. Briefly, Salmonella (SE/ST/SH) were grown in the presence or absence of the SICs of the LAB (LR, LP or LD) CFSN or MRS at 37 °C for 24 h. Following overnight growth, the cultures were washed and resuspended in RPMI 1640. For the internalization assay, activated and attached macrophages (105 cells/well) were infected with ~6.0 log10 CFU/well of each SE, ST, or SH separately. The tissue culture trays were centrifuged at 600× g for 5 min, and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator for 2 h. The unattached Salmonella were then removed by washing with RPMI, and fresh media supplemented with 100 µg/mL gentamicin was added. HTC monolayers were incubated further for an additional 1 h to kill any Salmonella attached to the surface. The media in the wells were changed every day with whole media containing 10 µg/mL gentamicin. The cells were washed thrice with PBS, lysed at 2, 24, 48, and 72 h using 0.1% Triton X-100 before serial dilution and plating to enumerate the surviving intracellular Salmonella population. The assay for each LAB CFSN and Salmonella strain was run in duplicate, and the entire experiment repeated three times.

3.8. Effect of LAB on Salmonella Virulence Gene Expression

SE-90, ST-43, and SH-V6FA (~6 log10 CFU/mL) were grown to the early stationary phase in LB broth supplemented with SICs of LAB (LR, LP or LD) CFSN or MRS at 37 °C [62]. RNA was isolated using RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quantification was performed using the Nanodrop (Eppendorf, Enfield, CT, USA), and cDNA was synthesized using the iScript reverse transcriptase kit (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA). cDNA was used as a template for the Salmonella virulence gene expression assay. Specific primers for candidate genes (motA, flgG, hilA, hilD, sipA, sipB, invH, sopB and spvB) were selected from the published literature [12]. The primers were custom synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, IA, USA). RT-qPCR was performed on the StepOnePlus™ platform using the SYBR green assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) under custom thermal cycling conditions. Duplicate samples were used for the assay, and the experiment was repeated three times. Data were normalized to the endogenous control (16s RNA), and comparative quantification (2−ΔΔCt) was performed to detect changes in relative gene expression between CFSN treated and untreated control (MRS) samples [63].

3.9. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis

TEM was performed according to the published protocol with some modifications [64]. Briefly, Salmonella (SE-90) grown in TSB supplemented with or without SIC of LR CFSN was centrifuged for 3000× g for 15 min, and the pellet was suspended in a fixative solution composed of 1.5% glutaraldehyde, 1.5% paraformaldehyde, 0.12 M phosphate buffer, and 3 mM magnesium chloride. Two percent molten agarose was poured onto the pellet and allowed to harden. The embedded pellet was then washed thrice with phosphate buffer (0.1 M phosphate buffer and 3 mM magnesium chloride) for 15 min each by slow rolling. The bacteria were fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M phosphate buffer and 3 mM magnesium chloride for an hour. Dehydration and clearing were performed for 10 min each in distilled water, 30%, 50%, 70%, 95%, and 100% ethanol, and finally in acetone. Embedment in the resin was done using one part resin and one part acetone for 2 h, two part epon/araldite resin and one part acetone for 17 h, and 100% resin for 3, 2.5, and 1.5 h. Finally, the pellet was infiltrated with pure resin, incubated at 60 °C for 48 h. For imaging, ultrathin sections (100 nm) of the resin block was transferred to 200 mesh copper grids and stained using 3% Sato’s lead citrate and 0.5% uranyl acetate. TEM images were taken using an FEI Tecnai™ microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA).

3.10. Statistical Analysis

Log10 values of Salmonella count at different time periods were tested for significance at a p value of <0.05 using the PROC GLIMMIX procedure of SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). For motility, adhesion, invasion, survival in HTC and RT-qPCR assays, the data were analyzed using the PROC-MIXED procedure of SAS. The results of two independent tests were tested for significance at a p value of <0.05 using MANOVA.

4. Conclusions

In summary, this study demonstrated the anti-Salmonella properties of select LAB cultures (LR, LP, and LD). The LAB isolates were able to adhere to intestinal epithelial cells and competitively exclude the pathogen. More specifically, the reduction in pathogen colonization (in vitro) was mediated by a significant inhibition of Salmonella enterica (S. Enteritidis 21 and 90, S. Typhimurium DT 104 43 and J380, and S. Heidelberg V6FA and 1) motility, attachment and invasion in CEC, and survival in chicken macrophages. In addition, our results revealed that LR, LP, and LD exerted their effects via the modulation of virulence gene expression in Salmonella. Furthermore, they were also found to be effective against multi-drug-resistant S. enterica serovars, namely S. Typhimurium DT104 and S. Heidelberg. Therefore, L. delbreuckii sub sp. bulgaricus NRRL B548, L. rhamnosus NRRL B442, and L. paracasei DUP-13076 could be potentially used to control Salmonella in chicken. However, further in vivo validation of these probiotic isolates in live birds is to be conducted.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Michael Darre, Department of Animal Science, University of Connecticut, Storrs, for providing chicken cecal tissue samples throughout the experiments. The authors would also like to thank Kumar Venkitanarayanan, Department of Animal Science, University of Connecticut, Storrs, for providing the BATC and Salmonella cultures used in the study. This research was funded by the USDA NIFA Hatch project through the Storrs Agricultural Experimentation Station (# CONS00940).

Author Contributions

Mary Anne Amalaradjou was involved in the experimental design and manuscript preparation. Muhammed Shafeekh Muyyarikkandy was involved in conducting the experiments, statistical analysis and manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Majowicz S.E., Musto J., Scallan E., Angulo F.J., Kirk M., O’Brien S.J., Jones T.F., Fazil A., Hoekstra R.M. International Collaboration on Enteric Disease ‘Burden of Illness’ Studies: The global burden of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010;50:882–889. doi: 10.1086/650733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scallan E., Hoekstra R.M., Angulo F.J., Tauxe R.V., Widdowson M.A., Roy S.L., Jones J.L., Griffin P.M. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—Major pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17:7–15. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.P11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antunes P., Mourao J., Campos J., Peixe L. Salmonellosis: The role of poultry meat. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016;22:110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson B.R., Griffin P.M., Cole D., Walsh K.A., Chai S.J. Outbreak-associated Salmonella enterica serotypes and food Commodities, United States, 1998–2008. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:1239–1244. doi: 10.3201/eid1908.121511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andino A., Hanning I. Salmonella Enterica: Survival, colonization, and virulence differences among serovars. Sci. World J. 2015;2015:520179. doi: 10.1155/2015/520179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajan K., Shi Z., Ricke S.C. Current aspects of Salmonella contamination in the US poultry production chain and the potential application of risk strategies in understanding emerging hazards. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2017;43:370–392. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2016.1223600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chousalkar K., Gast R., Martelli F., Pande V. Review of egg-related salmonellosis and reduction strategies in United States, Australia, United Kingdom and New Zealand. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2017;14:1–14. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2017.1368998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alali W.Q., Hofacre C.L. Preharvest food safety in broiler chicken production. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016;4 doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.PFS-0002-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chittick P., Sulka A., Tauxe R.V., Fry A.M. A summary of national reports of foodborne outbreaks of Salmonella Heidelberg infections in the United States: Clues for disease prevention. J. Food Prot. 2006;69:1150–1153. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-69.5.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gast R.K., Guraya R., Jones D.R., Anderson K.E., Karcher D.M. Colonization of internal organs by Salmonella Enteritidis in experimentally infected laying hens housed in enriched colony cages at different stocking densities. Poult. Sci. 2016;95:1363–1369. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He G., Tian W., Qian N., Cheng A., Deng S. Quantitative studies of the distribution pattern for Salmonella Enteritidis in the internal organs of chicken after oral challenge by a real-time PCR. Vet. Res. Commun. 2010;34:669–676. doi: 10.1007/s11259-010-9438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Upadhyaya I., Upadhyay A., Kollanoor-Johny A., Darre M.J., Venkitanarayanan K. Effect of plant derived antimicrobials on Salmonella Enteritidis adhesion to and invasion of primary chicken oviduct epithelial cells in vitro and virulence gene expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:10608–10625. doi: 10.3390/ijms140510608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey P.C., Watson M., Hulme S., Jones M.A., Lovell M., Berchieri A., Jr., Young J., Bumstead N., Barrow P. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium colonizing the lumen of the chicken intestine grows slowly and upregulates a unique set of virulence and metabolism genes. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:4105–4121. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01390-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berry E.D., Wells J.E. Reducing foodborne pathogen persistence and transmission in animal production environments: Challenges and opportunities. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016;4 doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.PFS-0006-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umaraw P., Prajapati A., Verma A.K., Pathak V., Singh V.P. Control of Campylobacter in poultry industry from farm to poultry processing unit: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017;57:659–665. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2014.935847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin J. Novel approaches for Campylobacter control in poultry. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2009;6:755–765. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2008.0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandeplas S., Dubois Dauphin R., Beckers Y., Thonart P., Thewis A. Salmonella in chicken: Current and developing strategies to reduce contamination at farm level. J. Food Prot. 2010;73:774–785. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-73.4.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fooks L.J., Gibson G.R. In vitro investigations of the effect of probiotics and prebiotics on selected human intestinal pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2002;39:67–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuller R. Probiotic in man and animals: A review. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1989;90:352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doré J., Corthier G. Le microbiote intestinal humain. Gastroentérologie Clinique et Biologique. 2010;34:7–16. doi: 10.1016/S0399-8320(10)70002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gusils C., Bujazha M., Gonzalez S. Preliminary studies to design a probiotic for use in swine feed. Interciencia. 2002;27:409–413. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Awad W.A., Ghareeb K., Abdel-Raheem S., Bohm J. Effects of dietary inclusion of probiotic and synbiotic on growth performance, organ weights, and intestinal histomorphology of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2009;88:49–56. doi: 10.3382/ps.2008-00244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stavric S., Kornegay E.T. Microbial probiotics for pigs and poultry. In: Wallace R.J., Chesson A., editors. Biotechnology in Animal Feeds and Feeding. Wiley-VCH; New York, NY, USA: 1995. pp. 205–231. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rolfe R.D. The role of probiotic cultures in the control of gastrointestinal health. J. Nutr. 2000;130:396S–402S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.396S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Upadhyaya I., Upadhyay A., Yin H.B., Nair M.S., Bhattaram V.K., Karumathil D., Kollanoor-Johny A., Khan M.I., Darre M.J., Curtis P.A., et al. Reducing Colonization and Eggborne Transmission of Salmonella Enteritidis in Layer Chickens by In-Feed Supplementation of Caprylic Acid. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2015;12:591–597. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2014.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller L.H., Benson C.E., Krotec K., Eckroade R.J. Salmonella Enteritidis colonization of the reproductive tract and forming and freshly laid eggs of chickens. Infect. Immun. 1995;63:2443–2449. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2443-2449.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gantois I., Ducatelle R., Pasmans F., Haesebrouck F., Gast R., Humphrey T.J., Van Immerseel F. Mechanisms of egg contamination by Salmonella Enteritidis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009;33:718–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muramoto K., Macnab R.M. Deletion analysis of MotA and MotB, components of the force-generating unit in the flagellar motor of Salmonella. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;29:1191–1202. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morimoto Y.V., Che Y.S., Minamino T., Namba K. Proton-conductivity assay of plugged and unplugged MotA/B proton channel by cytoplasmic pHluorin expressed in Salmonella. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1268–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Misselwitz B., Barrett N., Kreibich S., Vonaesch P., Andritschke D., Rout S., Weidner K., Sormaz M., Songhet P., Horvath P., et al. Near surface swimming of Salmonella Typhimurium explains target-site selection and cooperative invasion. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002810. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorkowski M., Felipe-Lopez A., Danzer C.A., Hansmeier N., Hensel M. Salmonella enterica invasion of polarized epithelial cells is a highly cooperative effort. Infect. Immun. 2014;82:2657–2667. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00023-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morimoto Y.V., Nakamura S., Kami-ike N., Namba K., Minamino T. Charged residues in the cytoplasmic loop of MotA are required for stator assembly into the bacterial flagellar motor. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;78:1117–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saijo-Hamano Y., Matsunami H., Namba K., Imada K. Expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of a core fragment of FlgG, a bacterial flagellar rod protein. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2013;69:547–550. doi: 10.1107/S1744309113008075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amy M.T., Virlogeux-Payant I., Bottreau E., Mompart F., Pardon P., Velge P. Precise excision and secondary transposition of TnphoA in non-motile mutants of a Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis clinical isolate. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005;245:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Immerseel F., De Buck J., De Smet I., Pasmans F., Haesebrouck F., Ducatelle R. Interactions of butyric acid- and acetic acid-treated Salmonella with chicken primary cecal epithelial cells in vitro. Avian Dis. 2004;48:384–391. doi: 10.1637/7094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee Y.K., Lim C.Y., Teng W.L., Ouwehand A.C., Tuomola E.M., Salminen S. Quantitative approach in the study of adhesion of lactic acid bacteria to intestinal cells and their competition with enterobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:3692–3697. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.9.3692-3697.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Porter S.B., Curtiss R. Effect of Inv Mutations on Salmonella Virulence and Colonization in 1-Day-Old White Leghorn Chicks. Avian Dis. 1997;41:45. doi: 10.2307/1592442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li S., Zhang Z., Pace L., Lillehoj H., Zhang S. Functions exerted by the virulence-associated type-three secretion systems during Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis invasion into and survival within chicken oviduct epithelial cells and macrophages. Avian Pathol. 2009;38:97–106. doi: 10.1080/03079450902737771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akbar S., Schechter L.M., Lostroh C.P., Lee C.A. AraC/XylS family members, HilD and HilC, directly activate virulence gene expression independently of HilA in Salmonella Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;47:715–728. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wood M.W., Jones M.A., Watson P.R., Hedges S., Wallis T.S., Galyov E.E. Identification of a pathogenicity island required for Salmonella enteropathogenicity. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;29:883–891. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang S., Santos R.L., Tsolis R.M., Stender S., Hardt W.-D., Baumler A.J., Adams L.G. The Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium effector proteins SipA, SopA, SopB, SopD, and SopE2 act in concert to induce diarrhea in calves. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:3843–3855. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3843-3855.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watson P.R., Galyov E.E., Paulin S.M., Jones P.W., Wallis T.S. Mutation of invH, but not stn, reduces Salmonella-induced enteritis in cattle. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:1432–1438. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1432-1438.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eichelberg K., Galan J.E. Differential regulation of Salmonella Typhimurium type III secreted proteins by pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1)-encoded transcriptional activators InvF and HilA. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:4099–4105. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4099-4105.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lucas R.L., Lee C.A. Roles of hilC and hilD in regulation of hilA expression in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:2733–2745. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.9.2733-2745.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shah D.H., Lee M., Park J., Lee J., Eo S., Kwon J., Chae J. Identification of Salmonella Gallinarum virulence genes in a chicken infection model using PCR-based signature-tagged mutagenesis. Microbiology. 2005;151:3957–3968. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pati N.B., Vishwakarma V., Jaiswal S., Periaswamy B., Hardt W.D., Suar M. Deletion of invH gene in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium limits the secretion of Sip effector proteins. Microbes Infect. 2013;15:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fields P.I., Swanson R.V., Haidaris C.G., Heffron F. Mutants of Salmonella Typhimurium that cannot survive within the macrophage are avirulent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:5189–5193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cirillo D.M., Valdivia R.H., Monack D.M., Falkow S. Macrophage-dependent induction of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system and its role in intracellular survival. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;30:175–188. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knodler L.A., Vallance B.A., Hensel M., Jäckel D., Finlay B.B., Steele-Mortimer O. Salmonella type III effectors PipB and PipB2 are targeted to detergent-resistant microdomains on internal host cell membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49:685–704. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Charles S. The Proteomic Response of the Probiotic Pediococcus acidilactici R1001 after Exposure to the Cell-Free Supernatant of the Pathogen Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 7644. MSc; UGuelph, ON, Canada: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kollanoor-Johny A., Mattson T., Baskaran S.A., Amalaradjou M.A., Babapoor S., March B., Valipe S., Darre M., Hoagland T., Schreiber D., et al. Reduction of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis colonization in 20-day-old broiler chickens by the plant-derived compounds trans-cinnamaldehyde and eugenol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:2981–2987. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07643-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Molina-Quiroz R.C., Silva C.A., Molina C.F., Leiva L.E., Reyes-Cerpa S., Contreras I., Santiviago C.A. Exposure to sub-inhibitory concentrations of cefotaxime enhances the systemic colonization of Salmonella Typhimurium in BALB/c mice. Open Biol. 2015;5 doi: 10.1098/rsob.150070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Niu C., Gilbert E.S. Colorimetric method for identifying plant essential oil components that affect biofilm formation and structure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:6951–6956. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.12.6951-6956.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amalaradjou M.A., Kim K.S., Venkitanarayanan K. Sub-inhibitory concentrations of trans-cinnamaldehyde attenuate virulence in Cronobacter sakazakii in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15:8639–8655. doi: 10.3390/ijms15058639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dodson S.V., Maurer J.J., Holt P.S., Lee M.D. Temporal changes in the population genetics of Salmonella Pullorum. Avian Dis. 1999;43:685–695. doi: 10.2307/1592738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Henderson S.C., Bounous D.I., Lee M.D. Early events in the pathogenesis of avian salmonellosis. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:3580–3586. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3580-3586.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hudson C.R., Quist C., Lee M.D., Keyes K., Dodson S.V., Morales C., Sanchez S., White D.G., Maurer J.J. Genetic relatedness of Salmonella isolates from nondomestic birds in Southeastern United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000;38:1860–1865. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.5.1860-1865.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nair D.V.T., Kollanoor-Johny A. Effect of Probionibacterium freudenreichii on Salmonella multiplication, motility, and association with avian epithelial cells. Poult. Sci. 2017;96:1513. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koo O.K., Amalaradjou M.A., Bhunia A.K. Recombinant probiotic expressing Listeria adhesion protein attenuates Listeria monocytogenes virulence in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e29277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kollanoor-Johny A., Mattson T., Baskaran S.A., Amalaradjou M.A., Hoagland T.A., Darre M.J., Khan M.I., Schreiber D.T., Donoghue A.M., Donoghue D.J., et al. Caprylic acid reduces Salmonella Enteritidis populations in various segments of digestive tract and internal organs of 3- and 6-week-old broiler chickens, therapeutically. Poult. Sci. 2012;91:1686–1694. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kannan L., Rath N.C., Liyanage R., Lay J.O., Jr. Identification and characterization of thymosin beta-4 in chicken macrophages using whole cell MALDI-TOF. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007;1112:425–434. doi: 10.1196/annals.1415.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bayoumi M.A., Griffiths M.W. In vitro inhibition of expression of virulence genes responsible for colonization and systemic spread of enteric pathogens using Bifidobacterium bifidum secreted molecules. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012;156:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bookout A.L., Mangelsdorf D.J. Quantitative real-time PCR protocol for analysis of nuclear receptor signaling pathways. Nucl. Recept. Signal. 2003;1:e012. doi: 10.1621/nrs.01012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berton V., Montesi F., Losasso C., Facco D.R., Toffan A., Terregino C. Study of the interaction between silver nanoparticles and Salmonella as revealed by transmission electron microscopy. J. Probiotics Health. 2015;3:123. [Google Scholar]