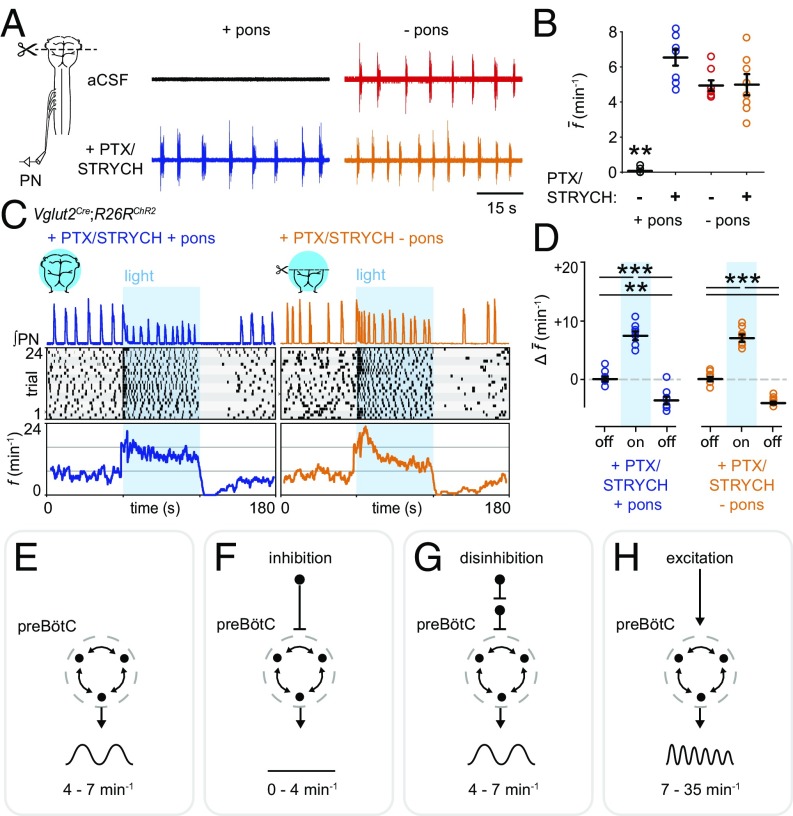

Fig. 1.

Excitation increases inspiratory frequency. (A, Top Left) Pontomedullary preparations do not exhibit spontaneous inspiration. (Top Right) Transection at the pontomedullary boundary initiates fictive inspiration. (Bottom Left) PTX/STRYCH application to pontomedullary preparations also initiates fictive inspiration. (Bottom Right) Fictive inspiration initiated via transection at the pontomedullary boundary is not affected by application of PTX/STRYCH. (B) Quantification of average f. **P < 0.01, artificial CSF (aCSF) + pons vs. all other conditions. (C, Top) After application of PTX/STRYCH, stimulation of excitatory neurons resulted in high-frequency inspiratory bursting (fmax + pons = 24.8 min−1; fmax − pons = 35.5 min−1). (Middle) Raster plots were constructed from eight biological replicates (each highlighted by gray shading), with three technical replicates each. (Bottom) f averaged over 24 trials relative to light onset. (D) Change in average f during and after light stimulation relative to baseline (off). PTX/STRYCH + pons: baseline vs. photostimulation, ***P = 1.3 × 10−5. Photostimulation vs. after, ***P = 1.0 × 10−7. Baseline vs. after, **P = 0.0012. PTX/STRYCH − pons: baseline vs. photostimulation, ***P = 3.2 × 10−6. Photostimulation vs. after, ***P = 1.5 × 10−7. Before vs. after, ***P = 2.1 × 10−6. Welch’s ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. n = 8 for each condition. Data are mean ± SEM. (E–H, Top and Middle) Illustration of tested hypothesis and output of preBötC. (Bottom) Summary of finding. (E) Baseline f. (F) Inhibition decreases f (A and B). (G) Disinhibition can return f to baseline frequency but does not increase f above baseline (A and B). (H) Excitation increases f above baseline (C and D).