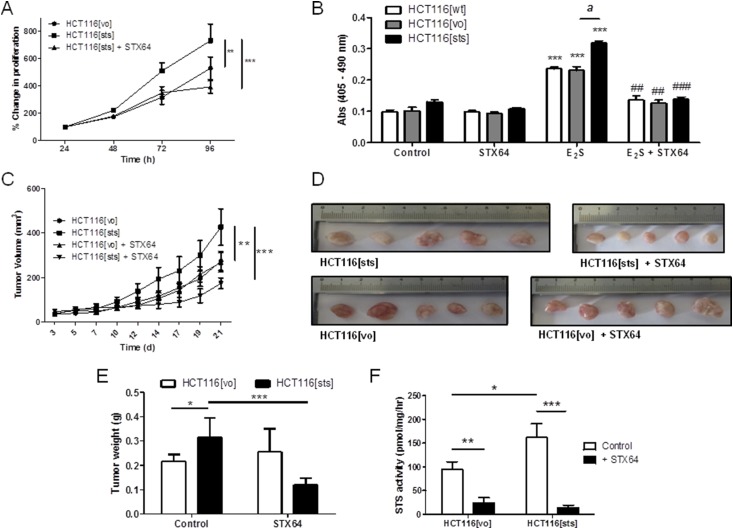

Figure 3.

Overexpression of STS in HCT116 cells increased estrogen-dependent proliferation in vitro and in vivo. (A) HCT116[sts] cells proliferated at a greater rate compared with HCT116[vo] cells. This proliferation was significantly inhibited by STX64 (1 mM). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (n = 3 independent experiments; one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison post-test). (B) HCT116[sts] cells had increased proliferation when stimulated with E2S (100 nM for 72 hours) compared with wild-type HCT116 (HCT116[wt]) and HCT116[vo] cells. This increased proliferation was blocked by STS inhibition using STX64 (1 mM). ***P < 0.001 compared with control; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 compared with E2S treatment; aP < 0.001 compared with HCT116[vo] (two-tailed Student t test used; n = 4 independent experiments). (C) HCT116[sts] xenografts grew at an increased rate compared with HCT116[vo] xenografts. This increased proliferation was inhibited by STX64 (20 mg/kg thrice weekly, orally). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison post-test). (D) Five randomly taken tumors imaged after removal. (E) Wet tumor weights at 21 days after HCT116 cell inoculation. HCT116[sts] resulted in an increased tumor burden, which was inhibited by STX64. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 (two-tailed Student t test used). (F) STS activity in HCT116[vo] and HCT116[sts] xenografts at day 21. HCT116[sts] xenograft maintained elevated STS activity compared with HCT116[vo]. STX64 treatment significantly inhibited HCT116[vo] and HCT116[sts] activity. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (n = 5 to 14; two-tailed Student t test used). All data presented as mean ± standard deviation.