Abstract

Objective

The present study was designed to determine the optimal cut-off values of body fat percentage (BF%) for the detection of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors in Mongolian and Han adults.

Method

This cross-sectional study involving 3221 Chinese adults (2308 Han and 913 Mongolian) aged 20–80 years was conducted in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China, in 2014. Data from a standardised questionnaire, physical examination and blood sample were obtained. The BF% was estimated using bioelectrical impedance analysis. Optimal BF% cut-offs were analysed by receiver operating characteristic curves to predict the risk of diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the OR of each CVD risk factor according to obesity defined by BF%.

Results

Mean BF% levels were lower in men than in women (22.54±5.77 vs 32.95±6.18 in Han, 23.86±5.72 vs 33.98±6.40 in Mongolian population, respectively; p<0.001). In Han population, the area under curve (AUC) values for BF% ranged from 0.589 to 0.699 for men and from 0.711 to 0.763 for women. Compared with men, AUCs for diabetes and clustering of ≥2 risk factors in women were significantly higher (p<0.05). The AUCs for BF% in women (0.685–0.783) were similar with those in men (0.686–0.736) for CVD risk factors in Mongolian population. In Han adults, the optimal BF% cut-off values to detect CVD risk factors varied from 18.7% to 24.2% in men and 32.7% to 35.4% in women. In Mongolian population, the optimal cut-off values of BF% for men and women ranged from 21.0% to 24.6% and from 35.7% to 40.0%, respectively. Subjects with high BF% (≥24% in men, ≥34% in women) had higher risk of CVD risk factors in Han (age-adjusted ORs from 1.479 to 3.680, 2.660 to 4.016, respectively). In Mongolia, adults with high BF% (≥25% in men, ≥35% in women) had higher risk of CVD risk factors (age-adjusted ORs from 2.587 to 3.772, 2.061 to 4.882, respectively).

Conclusions

The optimal BF% cut-offs for obesity for the prediction of CVD risk factors in Chinese men and women were approximately 24% and 34% for Han adults and 25% and 35% for Mongolian population of Inner Mongolia, China, respectively.

Keywords: body composition, obesity, cardiovascular risk factors

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The present study was first designed to determine the optimal cut-off values of body fat percentage (BF%) for cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors (hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidaemia) and clustering of ≥2 these risk factors in Chinese population.

This study used a large sample covering most age groups to estimate BF% cut-off values for discriminating CVD risk factors in both sexes, especially in different ethnics (Han and Mongolian) in China.

The prevention of public health problems was evaluated by PARP of BF% cut-offs in sexes and races.

The study characterises the optimal body fat percentage cut-off values for identifying CVD risk factors in a cross-sectional setting using the occurrence of established CVD risk factors as a proxy risk estimate. Lots of epidemic studies, especially prospective cohort studies, need to be completed to improve cut-off points accuracy of BF% in China.

BF% in this study was measured using bioelectrical impedance analysis, which tends to underestimate body fat in all subjects and in men and women separately. However, considering the convenience and inexpensiveness of bioelectrical impedance analysis, large-scale epidemiological investigations appropriately use this analysis.

Introduction

During the past four decades, the global prevalence of overweight and obesity has risen dramatically and is now estimated to affect over 600 million people.1 In China, the prevalence of obesity approximately tripled from 3.75% in 1991 to 11.3% in 2011 according to diagnostic criteria of the Working Group on Obesity.2 It is now identified that obesity essentially increases the risk of hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidaemia, which has a great influence on the morbidity and mortality of cardiovascular disease (CVD).3

Body mass index (BMI) closely correlated with body fatness is recommended by WHO as a population-level measure of overweight and obesity (BMI ≥30 or 25 kg/m2 is defined as obese or overweight). However, it may not consistently characterise adiposity across racial/ethnic groups.4 Body fat percentage (BF%) as a percentage of total bodyweight has advantages over BMI in estimating fat mass.5 The BF% cut-off points for obesity proposed by the WHO are 25% for men and 35% for women, corresponding a BMI of 30 kg/m2 in young Caucasians.6 It was reported that BMI and percentage of body fat differ across populations.7 The Chinese tend to have a lower BMI but a higher fat volume. Li et al 8 showed that the BF% cut-off values for Chinese adults were similar to those proposed by the WHO. However, a longitudinal epidemiological study9 reflected that the present Chinese BMI criteria (28 kg/m2 for obesity) was relatively inconsistent with WHO BF% criteria in determining obesity. Therefore, the appropriate BF% cut-off points for Chinese remains inconclusive and needs to be further studied. Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region located in northern China consists mainly of Han and Mongolian. Compared with Han population, the dietary pattern of Mongolians tends to be traditionally rich in whole milk, fats and oils, which might increase greater risk of obesity in Mongolia.10 In this study, we aimed to characterise the optimal BF% cut-off points in Mongolian and Han adults according to its risk for common CVD risk factors, including diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia.

Methods

Study population

The present study was based on data from the China National Health Survey (CNHS) in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in 2014, which has already been described in detail elsewhere.11 A total of 3508 examinees aged 20–80 years were found to be eligible for the study. We excluded individuals with incomplete data for hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidaemia status, sex, age and the anthropometric indices (ie, BMI, BF%). In addition, pregnant women were excluded. This resulted in a final analytical sample of 3221 adults (2308 Han and 913 Mongolian).

Written informed consent was acquired from each participant before data collection. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Data collection

A standardised health questionnaire was completed by investigators and contained demographic information, diseases (particularly hypertension and diabetes) and the family history of diabetes, cardiovascular disease or cancer. Anthropometric measurements including height, weight and body fat percentage were taken with the subjects after an overnight fast and wearing light clothes and without shoes in the morning. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a fixed stadiometer. Body weight was measured in an upright position to the nearest 0.1 kg. Body weight and body fat percentage was measured by bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), with a commercially available body analyser (BC-420, Tanita, Japan). BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared (kg/m2). Blood pressure was taken three times using the electronic sphygmomanometer (HEM-907, Omron, Japan), and the average was used as the mean blood pressure. All surveys were performed by trained staff.

Blood samples were collected from all participants following an overnight fast. Serum total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) were determined by the General Hospital of Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA).

Definition

Diabetes was defined as FPG ≥7.0 mmol/L and/or physician-diagnosed diabetes. Hypertension was defined as mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mm Hg and/or mean diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mm Hg and/or physician-diagnosed hypertension. Dyslipidaemia was defined as follow: TC ≥6.22 mmol/L and/or LDL-C ≥4.14 mmol/L and/or HDL-C <1.04 mmol/L and/or TG ≥2.26 mmol/L. Clustering of risk factors was defined as presence of ≥2 CVD risk factors. Overweight and obesity were defined as a subject with BMI≥25 and<30 kg/m2, and BMI≥30 kg/m2, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software V.9.3. Continuous variables were presented as mean±SD; comparisons between two groups were used by Student’s t-test. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and compared by χ2 test. Two-tailed p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed using BF% as continuous variable in logistic regression models to obtain accurate estimates of area under the cure (AUC) in relation to hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidaemia, which describe the probability that a test will correctly identify subjects with disease. The optimal cut-off values were defined as the points on the ROC curve where Youden’s index (sensitivity+specificity-1) was the maximal. ORs and the corresponding 95% CI were calculated by binary logistic regression analysis to measure the association between obesity defined by BF% and CVD risk factors. Per cent of prevalence of a condition/disease in the population (PARP) due to presence of risk factor or PARP that would be reduced if risk factor was removed for each CVD risk factor was calculated by sex-specific cut-offs for BF%. Formulas for calculation of PARP are given below.

PARP=100 * P (OR-1) / [P (OR-1)+1] %

(P, per cent of subjects whose BF% was above the sex-specific cut-off value; OR, age-adjusted ORs for cardiovascular risk factors in subjects using sex-specific cut-offs for BF%.)

Results

Base characteristics of subjects

Baseline characteristics for men and women in Han and Mongolian adults are shown in table 1. In Han adults, men had a higher mean BMI, SBP, DBP, FPG, TC and TG but a lower BF% and HDL-C than women. LDL-C was comparable between men and women (p>0.05). The prevalence of hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidaemia weas higher in men than in women. Similarly, in Mongolian adults, men had a higher mean BMI, SBP, DBP, FPG, TC, TG and LDL-C, whereas a lower BF% and HDL-C than women. The prevalence of CVD risk factors was higher in men than in women. In total, compared with Han population, Mongolian population had a higher mean weight, BMI, BF%, TC, LDL-C and HDL-C but a lower TG. Moreover, the prevalence of obesity and hypertension was higher in Mongolian than in Han.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by sex in Han and Mongolian adults

| Variables | Han (n=2308) | Mongolian (n=913) | ||||

| Men (n=898) | Women (n=1410) | All cases | Men (n=355) | Women (n=558) | All cases | |

| Age (years) | 46.20±14.05*** | 44.24±13.29 | 45.00±13.62 | 45.91±13.69** | 43.34±13.03 | 44.34±13.34 |

| Age groups (%) | *** | *** | ||||

| 20–49 | 58.02 | 66.52 | 63.21 | 57.75 | 68.64 | 64.40 |

| 50–80 | 41.98 | 33.48 | 36.79 | 42.25 | 31.36 | 35.60 |

| Height (cm) | 170.12±5.94*** | 158.28±5.51 | 162.89±8.10 | 170.54±6.35*** | 158.53±5.46 | 163.21±8.26 |

| Weight (kg) | 72.92±12.18*** | 60.20±9.70 | 65.15±12.39### | 75.11±12.96*** | 61.54±10.08 | 66.82±13.08 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.17±3.82*** | 24.04±3.72 | 24.48±3.80### | 25.78±3.96*** | 24.52±4.07 | 25.01±4.07 |

| BMI groups (%) | *** | ### | *** | |||

| Overweight | 40.42 | 34.04 | 36.53 | 41.41 | 37.28 | 38.88 |

| Obesity | 21.71 | 14.04 | 17.03 | 28.45 | 17.92 | 22.02 |

| BF% | 22.54±5.77*** | 32.95±6.18 | 28.90±7.88### | 23.86±5.72*** | 33.98±6.40 | 30.05±7.88 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 127.40±14.96*** | 119.07±17.14 | 122.31±16.82 | 129.4±16.05*** | 118.22±17.65 | 122.57±17.89 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 80.21±10.52*** | 75.42±10.66 | 77.28±10.86 | 82.2±11.89*** | 75.67±11.96 | 78.21±12.34 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 5.53±1.49*** | 5.22±1.08 | 5.34±1.27 | 5.56±1.48*** | 5.14±1.09 | 5.30±1.27 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.86±1.00* | 4.76±1.04 | 4.80±1.03### | 5.10±0.97*** | 4.89±1.03 | 4.98±1.02 |

| TG(mmol/L) | 2.18±1.89*** | 1.55±1.13 | 1.80±1.50## | 2.00±1.46*** | 1.46±1.18 | 1.67±1.32 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.86±0.86 | 2.83±0.85 | 2.84±0.86### | 3.13±0.87*** | 2.93±0.86 | 3.01±0.87 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.19±0.32*** | 1.39±0.34 | 1.31±0.34### | 1.27±0.34*** | 1.45±0.37 | 1.38±0.37 |

| Hypertension (%) | 33.74*** | 23.48 | 27.47# | 40.28*** | 25.63 | 31.33 |

| Diabetes (%) | 9.58*** | 5.53 | 7.11 | 9.86*** | 3.23 | 5.81 |

| Dyslipidaemia (%) | 51.11*** | 27.73 | 36.83 | 47.32*** | 26.34 | 34.50 |

| Risk factors ≥2(%) | 24.16*** | 12.20 | 16.85 | 27.32*** | 13.80 | 19.06 |

Values are means±SD or %.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 compared with women within Han or Mongolian adults.

#p<0.05, ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001 compared with Mongolian adults (Student’s t-tests for continuous variables; χ2 tests for categorical variables).

BF%, body fat percentage; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

Area under ROC and optimal cut-offs for predicting CVD risk factors

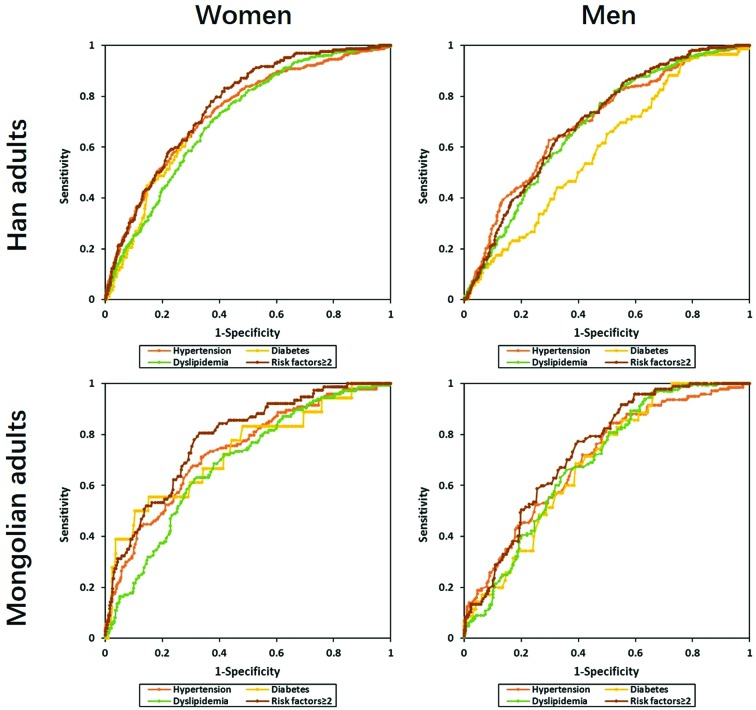

Figure 1 shows ROC curves of BF% for identifying CVD risk factors in men and women among Han and Mongolian adults. Area under ROC curves of BF% stratified by age groups are summarised in table 2. In Han population, the AUC of BF% ranged from 0.589 to 0.699 for men and from 0.711 to 0.763 for women. Compared with men, AUCs for diabetes and clustering of ≥2 risk factors in women were significantly higher (p<0.05). In addition, the AUC for CVD risk factors were larger in the younger age group than that in the older in women (p<0.05). However, AUCs for cardiovascular risk factors were all comparable between men and women in Mongolian adults (p>0.05). Among these, the AUCs of BF% ranged from 0.686 to 0.736 for men and from 0.685 to 0.783 for women. Although BF% performed differently for CVD risk factors in age groups of both sexes, there were no significant difference in the AUCs (p>0.05).

Figure 1.

ROC curves for BF% screening CVD risk factors in men and women among Han and Mongolian adults. BF%, body fat percentage; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Table 2.

Area under receiver operating characteristic curves of body fat percentage screening cardiovascular disease risk factors

| Hypertension | Diabetes | Dyslipidaemia | Risk factors ≥2 | |

| Han | ||||

| Men | ||||

| All ages | 0.696 (0.661, 0.732) | 0.589 (0.531, 0.648) | 0.682 (0.647, 0.717) | 0.699 (0.662, 0.736) |

| 20–49 years | 0.734 (0.686, 0.782) | 0.532 (0.417, 0.646) | 0.700 (0.655, 0.745) | 0.731 (0.681, 0.780) |

| 50–80 years | 0.666 (0.611, 0.720) | 0.606 (0.536, 0.676) | 0.661 (0.607, 0.716) | 0.670 (0.613, 0.726) |

| Women | ||||

| All ages | 0.737 (0.707, 0.767) | 0.728 (0.676, 0.780) * | 0.711 (0.683, 0.740) | 0.763 (0.729, 0.797) * |

| 20–49 years | 0.761 (0.718, 0.805) | 0.787 (0.700, 0.874) | 0.735 (0.698, 0.773) | 0.836 (0.788, 0.885) |

| 50–80 years | 0.645 (0.595, 0.695) # | 0.617 (0.544, 0.689) # | 0.596 (0.545, 0.646) # | 0.644 (0.590, 0.698) # |

| Mongolian | ||||

| Men | ||||

| All ages | 0.702 (0.648, 0.757) | 0.686 (0.609, 0.764) | 0.690 (0.636, 0.745) | 0.736 (0.683, 0.789) |

| 20–49 years | 0.714 (0.636, 0.793) | 0.765 (0.646, 0.884) | 0.681 (0.608, 0.753) | 0.764 (0.688, 0.839) |

| 50–80 years | 0.665 (0.577, 0.754) | 0.609 (0.498, 0.720) | 0.689 (0.604, 0.775) | 0.689 (0.606, 0.772) |

| Women | ||||

| All ages | 0.733 (0.685, 0.780) | 0.733 (0.601, 0.865) | 0.685 (0.637, 0.733) | 0.783 (0.730, 0.835) |

| 20–49 years | 0.643 (0.557, 0.729) | 0.729 (0.616, 0.842) | 0.670 (0.604, 0.735) | 0.764 (0.666, 0.863) |

| 50–80 years | 0.683 (0.604, 0.763) | 0.664 (0.481, 0.848) | 0.586 (0.502, 0.671) | 0.690 (0.607, 0.773) |

*p<0.05, compared with men.

#p<0.05, compared with 20–49 years.

Optimal cut-off points of BF% for CVD risk factors in both ethnic groups were given in table 3, which were identified according to the highest Youden’s index on ROC curves. In Han adults, the BF% cut-off values were found to optimally predict the risk of hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidaemia varied from 18.7% to 24.2% in men and 32.7% to 35.4% in women. In addition, the optimal cut-off points of BF% were all higher for women than for men in each CVD risk factor. In Mongolian, the optimal BF% cut-off values for men and women ranged from 21.0% to 24.6% and from 35.7% to 40.0%, respectively. The optimal BF% cut-offs between men and women in Mongolian adults were remarkably different. Basically, the optimal cut-off values of BF% in women were mostly higher for older age group than for the younger in Han and Mongolian adults. However, the optimal BF% cut-off points varied greatly by age and CVD risk factors.

Table 3.

Optimal cut-off values of BF% and their sensitivities, specificities and Youden's index for CVD risk factors by age groups and sex

| Hypertension | Diabetes | Dyslipidemia | Risk factors ≥2 | |||||||||||||

| Cut-off | Sen | Spe | YI | Cut-off | Sen | Spe | YI | Cut-off | Sen | Spe | YI | Cut-off | Sen | Spe | YI | |

| Han | ||||||||||||||||

| Men | ||||||||||||||||

| All ages | 24.2 | 62.7 | 70.3 | 33.0 | 18.7 | 94.2 | 23.5 | 17.7 | 21.6 | 77.3 | 52.4 | 29.7 | 24.2 | 64.5 | 66.7 | 31.2 |

| 20–49 years | 24.2 | 69.3 | 71.1 | 40.4 | 18.8 | 92.3 | 24.6 | 17.0 | 21.6 | 75.8 | 56.0 | 31.9 | 24.2 | 68.4 | 67.8 | 36.3 |

| 50–80 years | 24.2 | 58.0 | 68.7 | 26.6 | 22.5 | 75.0 | 45.1 | 20.1 | 20.5 | 87.1 | 41.9 | 29.0 | 25.0 | 54.9 | 71.8 | 26.7 |

| Women | ||||||||||||||||

| All ages | 34.2 | 71.9 | 64.8 | 36.7 | 35.4 | 69.2 | 67.5 | 36.7 | 32.7 | 77.2 | 55.8 | 33.1 | 33.7 | 83.1 | 58.1 | 41.2 |

| 20–49 years | 33.6 | 73.7 | 67.2 | 40.9 | 32.0 | 94.4 | 52.6 | 47.1 | 33.9 | 66.1 | 70.3 | 36.5 | 33.9 | 90.5 | 65.6 | 56.1 |

| 50–80 years | 36.8 | 52.6 | 70.7 | 23.2 | 35.4 | 70.0 | 51.2 | 21.2 | 34.8 | 66.8 | 50.6 | 17.4 | 36.7 | 56.9 | 65.5 | 22.4 |

| Mongolian | ||||||||||||||||

| Men | ||||||||||||||||

| All ages | 23.0 | 84.6 | 48.1 | 32.7 | 21.9 | 97.1 | 33.4 | 30.6 | 21.0 | 89.3 | 41.7 | 31.0 | 24.6 | 77.3 | 60.1 | 37.4 |

| 20–49 years | 23.0 | 87.3 | 51.3 | 38.6 | 26.8 | 75.0 | 75.1 | 50.1 | 18.5 | 94.5 | 35.1 | 29.6 | 25.7 | 72.2 | 71.6 | 43.8 |

| 50–80 years | 21.9 | 88.6 | 40.3 | 29.0 | 22.0 | 95.7 | 28.3 | 24.0 | 21.0 | 94.8 | 38.4 | 33.2 | 21.9 | 96.7 | 37.1 | 33.8 |

| Women | ||||||||||||||||

| All ages | 35.7 | 71.3 | 66.3 | 37.6 | 40.0 | 55.6 | 84.6 | 40.2 | 36.4 | 62.6 | 68.6 | 31.2 | 36.4 | 80.5 | 66.9 | 47.5 |

| 20–49 years | 35.7 | 55.6 | 70.7 | 26.3 | 34.8 | 100.0 | 61.8 | 61.8 | 31.1 | 82.9 | 43.5 | 26.3 | 36.4 | 70.0 | 74.1 | 44.1 |

| 50–80 years | 36.7 | 73.5 | 54.5 | 28.0 | 41.0 | 60.0 | 81.3 | 41.3 | 36.5 | 77.9 | 46.9 | 24.9 | 36.6 | 84.2 | 46.6 | 30.8 |

BF%, body fat percentage; CVD, cardiovascular disease; Sen, sensitivity; Spe, specificity; YI, Youden's index.

The optimal cut-offs of BF% for identifying CVD risk factors in Han and Mongolian adults were also assessed. Table 4 table 5 show the sensitivity, specificity and Youden’s index for the various cut-off values for BF% in men and women. Clearly, specificity gradually increased but sensitivity conversely decreased with the increase cut-off values of BF% in men and women. BF% cut-off points of preferable sensitivity and specificity to detect each CVD risk factor and clustering of ≥2 risk factors were selected as optimal values. In Han population, 24% and 34% were the optimal BF% cut-off values in terms of the Youden’s index, sensitivity and specificity for men and women, respectively. In Mongolian, the optimal cut-off points of BF% were 25% for men and 35% for women.

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity and Youden’s index for BF% to detect CVD risk factors by sex-specific cut-offs in Han adults

| Hypertension | Diabetes | Dyslipidemia | Risk factors ≥2 | |||||||||

| Sen | Spe | YI | Sen | Spe | YI | Sen | Spe | YI | Sen | Spe | YI | |

| Men | ||||||||||||

| 21 | 83.8 | 41.3 | 25.2 | 79.1 | 34.1 | 13.2 | 81.1 | 47.4 | 28.4 | 88.0 | 39.5 | 27.5 |

| 22 | 77.6 | 49.4 | 27.0 | 70.9 | 41.5 | 12.4 | 73.4 | 54.7 | 28.1 | 81.1 | 47.1 | 28.3 |

| 23 | 69.6 | 59.2 | 28.8 | 61.6 | 50.6 | 12.3 | 63.8 | 63.3 | 27.2 | 72.4 | 56.4 | 28.7 |

| 24 | 64.0 | 67.1 | 31.1 | 53.5 | 57.6 | 11.1 | 56.0 | 69.7 | 25.7 | 66.4 | 63.9 | 30.2 |

| 25 | 52.5 | 74.5 | 26.9 | 44.2 | 66.4 | 10.6 | 45.3 | 76.5 | 21.9 | 55.8 | 72.1 | 27.9 |

| 26 | 43.9 | 81.3 | 25.2 | 33.7 | 73.5 | 7.2 | 51.1 | 81.3 | 32.4 | 44.7 | 78.4 | 23.1 |

| Women | ||||||||||||

| 32 | 84.0 | 50.5 | 34.5 | 89.7 | 44.3 | 34.0 | 80.3 | 51.1 | 31.4 | 91.3 | 47.1 | 38.4 |

| 33 | 78.6 | 56.9 | 35.5 | 82.1 | 50.4 | 32.4 | 74.7 | 57.5 | 32.2 | 85.5 | 53.3 | 38.8 |

| 34 | 72.2 | 63.2 | 35.4 | 75.6 | 56.7 | 32.3 | 68.3 | 63.8 | 32.1 | 79.7 | 59.7 | 39.3 |

| 35 | 64.4 | 70.9 | 35.3 | 70.5 | 64.6 | 35.1 | 58.6 | 70.8 | 29.3 | 69.8 | 67.1 | 36.9 |

| 36 | 55.6 | 77.3 | 32.9 | 62.8 | 71.5 | 34.3 | 48.3 | 76.5 | 24.8 | 61.1 | 73.8 | 34.9 |

| 37 | 47.7 | 82.7 | 30.4 | 53.9 | 77.3 | 31.1 | 38.9 | 81.1 | 19.9 | 52.3 | 79.4 | 31.7 |

BF%, body fat percentage; CVD, cardiovascular disease; Sen, sensitivity; Spe, specificity; YI, Youden's index.

Table 5.

Sensitivity, specificity and Youden’s index for BF% to detect CVD risk factors by sex-specific cut-offs in Mongolian adults

| Hypertension | Diabetes | Dyslipidaemia | Risk factors ≥2 | |||||||||

| Sen | Spe | YI | Sen | Spe | YI | Sen | Spe | YI | Sen | Spe | YI | |

| Men | ||||||||||||

| 21 | 88.1 | 37.3 | 25.4 | 97.1 | 29.7 | 26.8 | 89.3 | 41.7 | 31.0 | 95.9 | 35.7 | 31.5 |

| 22 | 86.7 | 43.4 | 30.1 | 94.3 | 34.1 | 28.4 | 82.7 | 43.9 | 26.6 | 93.8 | 40.7 | 34.5 |

| 23 | 84.6 | 48.1 | 32.7 | 88.6 | 37.5 | 26.1 | 81.0 | 49.2 | 30.2 | 91.8 | 45.0 | 36.7 |

| 24 | 72.7 | 54.7 | 27.5 | 82.9 | 46.6 | 29.4 | 69.1 | 55.1 | 24.1 | 79.4 | 52.3 | 31.7 |

| 25 | 60.8 | 64.2 | 25.0 | 71.4 | 56.9 | 28.3 | 60.1 | 66.8 | 27.0 | 70.1 | 63.2 | 33.3 |

| 26 | 53.2 | 72.2 | 25.3 | 60.0 | 64.4 | 24.4 | 49.4 | 72.2 | 21.6 | 60.8 | 70.5 | 31.4 |

| Women | ||||||||||||

| 32 | 84.6 | 42.9 | 27.5 | 83.3 | 36.5 | 19.8 | 81.6 | 42.1 | 23.7 | 92.2 | 40.3 | 32.5 |

| 33 | 79.7 | 48.9 | 28.6 | 83.3 | 42.4 | 25.7 | 76.9 | 48.2 | 25.1 | 88.3 | 46.4 | 34.7 |

| 34 | 75.5 | 54.7 | 30.2 | 83.3 | 48.0 | 31.3 | 73.5 | 54.3 | 27.7 | 85.7 | 52.2 | 37.9 |

| 35 | 73.4 | 62.2 | 35.6 | 77.8 | 54.1 | 31.9 | 68.7 | 60.8 | 29.5 | 84.4 | 59.0 | 43.5 |

| 36 | 68.5 | 67.0 | 35.5 | 66.7 | 58.7 | 25.4 | 63.3 | 65.5 | 28.7 | 80.5 | 64.0 | 44.6 |

| 37 | 58.7 | 73.5 | 32.2 | 61.1 | 66.1 | 27.2 | 55.1 | 72.5 | 27.6 | 70.1 | 70.9 | 41.0 |

BF%, body fat percentage; CVD, cardiovascular disease; Sen, sensitivity; Spe, specificity; YI, Youden's index.

The age-adjusted OR (95% CI) and PARP of each CVD risk factor using sex-specific cut-offs for BF% in Han and Mongolian adults are shown in table 6. In Han adults, BF% corresponded to significantly higher OR for hypertension and dyslipidaemia in men except diabetes, while BF% corresponded to significantly higher OR for all CVD risk factors in women. In Mongolian population, BF% corresponded to significantly higher OR for all CVD risk factors in both sexes except diabetes in women. According to PARP analysis, the proportion of Han adults whose BF%≥24% was about 43% in men. If BF% was controlled below 24%, 53.8% of hypertension, 17.2% of diabetes, 46.1% of dyslipidaemia and 51.6% of clustering of ≥2 CVD risk factors would be prevented. Women whose BF%≥34% was about 45% in Han women. If BF% was controlled under 24%, 57.6% of clustering of ≥2 risk factors would be prevented. In Mongolian population, the proportions of subjects whose BF% above 25% for men and 35% for women were round 46% and 47%, respectively. If BF% was controlled under 25% for men and 35% for women, 56%–65% of clustering of ≥2 risk factors would be prevented.

Table 6.

Age-adjusted OR (95% CI) and PARP of each CVD risk factor by sex-specific cut-offs for BF% in Han and Mongolian adults

| OR* | 95% CI | PARP(%) | |

| Han | |||

| Men (BF%≥24%) | |||

| Hypertension | 3.680 | 2.728 to 4.964 | 53.8 |

| Diabetes | 1.479 | 0.940 to 2.328 | 17.2 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 2.966 | 2.251 to 3.908 | 46.1 |

| Risk factors ≥2 | 3.450 | 2.490 to 4.780 | 51.6 |

| Women (BF%≥34%) | |||

| Hypertension | 3.382 | 2.544 to 4.494 | 51.8 |

| Diabetes | 2.660 | 1.539 to 4.596 | 42.8 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 3.152 | 2.439 to 4.072 | 49.3 |

| Risk factors ≥2 | 4.016 | 2.682 to 6.014 | 57.6 |

| Mongolian | |||

| Men (BF%≥25%) | |||

| Hypertension | 2.587 | 1.635 to 4.094 | 42.2 |

| Diabetes | 2.982 | 1.374 to 6.471 | 47.6 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 2.986 | 1.930 to 4.620 | 47.7 |

| Risk factors≥2 | 3.772 | 2.251 to 6.321 | 56.0 |

| Women (BF%≥35%) | |||

| Hypertension | 2.851 | 1.796 to 4.526 | 46.5 |

| Diabetes | 2.061 | 0.634 to 6.697 | 33.3 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 2.599 | 1.704 to 3.964 | 42.9 |

| Risk factors≥2 | 4.882 | 2.497 to 9.545 | 64.6 |

*Adjusted ORs for CVDs in subjects using sex-specific cut-offs for BF%, adjusted for age.

BF%, body fat percentage; CVD, cardiovascular disease; PARP, population attributable risk proportion.

Discussion

The present study, using data obtained from Han and Mongolian adults from Inner Mongolia, China showed that BF% performed differently for discriminating CVD risk factors in sex and ethnicity. The optimal BF% cut-off points for men and women were approximately 24.0% and 34.0% in Han adults, and 25.0% and 35.0% in Mongolian population, respectively. Compared with WHO criteria, the optimal BF% cut-offs in this study were a little lower in Han adults, but similar in Mongolian, which were taken account of validity to detect CVD risk factors and clustering two or more CVD risk factors.

BMI is the most widely used measure to diagnose obesity. However, the accuracy of BMI in detecting excess body adiposity in the general adult population is limited, because it cannot measure BF% directly and poorly distinguishes among total body fat, total body lean and bone mass.12 13 To overcome misclassifications, direct measurements of BF% would be a better tool for diagnosing obesity. Moreover, BF% has been found to have a strong association with multiple CVD risk factors in several studies conducted in China,8 Korea14 and other ethnic groups.15–17 Our data also support the good discrimination of BF% for each CVD risk factor and clustering of ≥2 risk factors in both sexes and ethnicities. However, BF% seems performed better in women than in men to detect CVD risk factors, which might result from greater less mass and lower fat mass men had than women.18 Besides, BF% had larger AUCs for almost CVD risk factors in women aged <50 years than in the older women, but not obviously in men. In a Korean study, women after menopause had not only higher total body fat percentage but also its different distribution, which independently correlates with CVD risk factors.19 In addition, a study of 402 women aged 30–75 years in Southern India also showed that menopausal status and associated obesity created a compatible atmosphere for abnormal metabolism and aggravated cardio-metabolic risk factors.20 However, the relationship between obesity in women after menopause and CVD risk factors is more vulnerable to the effect of confounding variables, such as ageing, which might affect the accuracy of prediction of BF% for CVD risk factors.

It has been demonstrated that adipose tissue distribution varies among different ethnicities.21 As is well known, the increased risks of metabolic diseases associated with obesity occur at lower BMIs in Asians, and these population are predisposed to visceral or abdominal obesity. In a study of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women in Thai, 34% was proposed as the optimal BF% cut-off points to identify women at risk of metabolic syndrome.22 In addition, a cross-sectional study of the middle-aged Japanese men shown that the cut-off point of BF% for detecting participants with one or more CVD risk factors (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidaemia) was 20.3%.23 Joseph et al recommended an optimal BF% cut-off values of 25.5 in men and 38.0 in women for Asian Indian individuals.24 Furthermore, Kim, et al reported that a BF% of 21% for men and 37% for women may be the appropriate cut-off values in Korean adults.25 These discrepancies mainly result from different ethnic groups, age and outcome. By now, BF% has not been recommended as an adiposity index in the Chinese population yet, and there has been little study on the cut-off point for BF%. Li et al proposed 25% and 35% as optimal BF% cut-off points for Chinese men and women to predict metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes using data from the Shanghai Diabetes Studies, respectively.8 In this study, the optimal cut-off values of BF% to detect diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia for men and women in Han adults were found to be 24% and 34%, respectively. In Mongolian population, the optimal BF% cut-offs were 25% for men and 35% for women. Mongolians have a distinctive lifestyle and dietary habits characterised by a preference for high protein and fatty foods of animal origin,26 which is different from Han population. Zhang et al reported the prevalence of overweight or obesity was higher in Mongolian people than Han people using WHO criteria (26.1% vs 21.3%, respectively).27 Moreover, a study evaluating the relationship among ethnic groups and their CVD risk factors (hypertension, obesity, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, smoking) showed that clustering of ≥2 or ≥3 of these risk factors was noted in 66.9% or 36.5% of Mongolian as well as 62.0% or 28.3% of Han subjects, respectively.28 Because of different genetic backgrounds, lifestyles and dietary patterns, the optimal BF% cut-offs of Han adults may not be the same as Mongolian.

There are some limitations to our study. A major limitation of the present study is cross-sectional design, which cannot be used to establish temporal relationship and causality. Lots of epidemic studies, especially prospective cohort studies, need to be completed to improve cut-off points accuracy of BF% in China. Second, BF% in this study was measured using bioelectrical impedance analysis, which tends to underestimate body fat in all subjects and in men and women separately.29 However, considering the convenience and inexpensiveness of BIA, large-scale epidemiological investigations appropriately use this analysis. Finally, the subjects were from Inner Mongolia, so the study’s findings cannot necessarily be representative of all Chinese adults, especially Han people.

The current definitions of obesity using BF% are based on Western populations and probably need to be modified for Chinese population. The present study showed the optimal BF% cut-off points for men and women were around 24.0% and 34.0% in Han adults, and 25.0% and 35.0% in Mongolian population of Inner Mongolia, China, respectively. Considering the rapid growth of obesity in China,2 these optimal body fat percentage cut-offs will contribute to public health prevention and intervention.

bmjopen-2016-014675supp001.doc (93.5KB, doc)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We sincerely express our gratitude to all the staff of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Center for Disease Control and Prevention for support with the collection of demographic data.

Footnotes

Contributors: YL participated in the data collection and drafted the manuscript. HW, WW, HG, YQ, GX, GL participated in the data collection. KW, FD, LP, GZ, GS participated in the design of the study and undertook statistical analyses. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Science & Technology Pillar Program during the 12th Five-Year Plan period, Grant 2012BAI37B02 from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Beijing, People’s Republic of China to GS, which enabled the completion of the project.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Refer-ences

- 1. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. Lancet 2016;387:1377–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mi YJ, Zhang B, Wang HJ, et al. Prevalence and secular trends in obesity among Chinese adults, 1991-2011. Am J Prev Med 2015;49:661–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lavie CJ, McAuley PA, Church TS, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular diseases: implications regarding fitness, fatness, and severity in the obesity paradox. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1345–54. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Habib SS. Body mass index and body fat percentage in assessment of obesity prevalence in saudi adults. Biomed Environ Sci 2013;26:94–9. 10.3967/0895-3988.2013.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meeuwsen S, Horgan GW, Elia M. The relationship between BMI and percent body fat, measured by bioelectrical impedance, in a large adult sample is curvilinear and influenced by age and sex. Clin Nutr 2010;29:560–6. 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. report of a WHO expert committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1995;854:1–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deurenberg P, Deurenberg-Yap M. Validity of body composition methods across ethnic population groups. Acta Diabetol 2003;40(Suppl 1):s246–49. 10.1007/s00592-003-0077-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li L, Wang C, Bao Y, et al. Optimal body fat percentage cut-offs for obesity in Chinese adults. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2012;39:393–8. 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2012.05684.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang C, Hou XH, Zhang ML, et al. Comparison of body mass index with body fat percentage in the evaluation of obesity in Chinese. Biomed Environ Sci 2010;23:173–9. 10.1016/S0895-3988(10)60049-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dugee O, Khor GL, Lye MS, et al. Association of major dietary patterns with obesity risk among mongolian men and women. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2009;18:433–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li G, Wang H, Wang K, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, control and risk factors related to hypertension among urban adults in Inner Mongolia 2014: differences between Mongolian and Han populations. BMC Public Health 2016;16:294 10.1186/s12889-016-2965-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, et al. Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. Int J Obes 2008;32:959–66. 10.1038/ijo.2008.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goonasegaran AR, Nabila FN, Shuhada NS. Comparison of the effectiveness of body mass index and body fat percentage in defining body composition. Singapore Med J 2012;53:403–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim JY, Han SH, Yang BM. Implication of high-body-fat percentage on cardiometabolic risk in middle-aged, healthy, normal-weight adults. Obesity 2013;21:1571–7. 10.1002/oby.20020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gómez-Ambrosi J, Silva C, Galofré JC, et al. Body adiposity and type 2 diabetes: increased risk with a high body fat percentage even having a normal BMI. Obesity 2011;19:1439–44. 10.1038/oby.2011.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lamb MM, Ogden CL, Carroll MD, et al. Association of body fat percentage with lipid concentrations in children and adolescents: United States, 1999-2004. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:877–83. 10.3945/ajcn.111.015776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shea JL, King MT, Yi Y, et al. Body fat percentage is associated with cardiometabolic dysregulation in BMI-defined normal weight subjects. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2012;22:741–7. 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hodge S, Bunting BP, Carr E, et al. Obesity, whole blood serotonin and sex differences in healthy volunteers. Obes Facts 2012;5:399–407. 10.1159/000339981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Park JK, Lim YH, Kim KS, et al. Body fat distribution after menopause and cardiovascular disease risk factors: Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010. J Womens Health 2013;22:587–94. 10.1089/jwh.2012.4035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dasgupta S, Salman M, Lokesh S, et al. Menopause versus aging: the predictor of obesity and metabolic aberrations among menopausal women of Karnataka, South India. J Midlife Health 2012;3:24–30. 10.4103/0976-7800.98814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carroll JF, Chiapa AL, Rodriquez M, et al. Visceral fat, waist circumference, and BMI: impact of race/ethnicity. Obesity 2008;16:600–7. 10.1038/oby.2007.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bintvihok W, Chaikittisilpa S, Panyakamlerd K, et al. Cut-off value of body fat in association with metabolic syndrome in Thai peri- and postmenopausal women. Climacteric 2013;16:393–7. 10.3109/13697137.2012.762762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yamashita K, Kondo T, Osugi S, et al. The significance of measuring body fat percentage determined by bioelectrical impedance analysis for detecting subjects with cardiovascular disease risk factors. Circ J 2012;76:2435–42. 10.1253/circj.CJ-12-0337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Joseph L, Wasir JS, Misra A, et al. Appropriate values of adiposity and lean body mass indices to detect cardiovascular risk factors in Asian Indians. Diabetes Technol Ther 2011;13:899–906. 10.1089/dia.2011.0014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim CH, Park HS, Park M, et al. Optimal cutoffs of percentage body fat for predicting obesity-related cardiovascular disease risk factors in Korean adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:34–9. 10.3945/ajcn.110.001867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Otgontuya D, Khor GL, Lye MS, et al. Obesity among mongolian adults from urban and rural areas. Malays J Nutr 2009;15:185–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang X, Sun Z, Zheng L, et al. Ethnic differences in overweight and obesity between Han and Mongolian rural Chinese. Acta Cardiol 2009;64:239–45. 10.2143/AC.64.2.2036144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li N, Wang H, Yan Z, et al. Ethnic disparities in the clustering of risk factors for cardiovascular disease among the Kazakh, Uygur, Mongolian and Han populations of Xinjiang: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:499 10.1186/1471-2458-12-499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sun G, French CR, Martin GR, et al. Comparison of multifrequency bioelectrical impedance analysis with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for assessment of percentage body fat in a large, healthy population. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:74–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014675supp001.doc (93.5KB, doc)