Figure 5.

Selection in Hypermutator Tumors

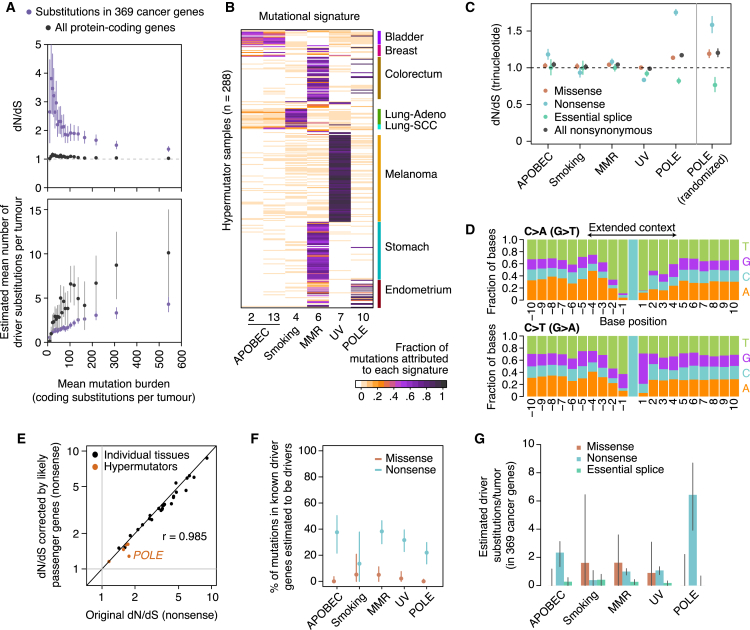

(A) dN/dS and estimated number of driver mutations per tumor grouping samples in 20 equal-sized bins according to mutation burden. This analysis excludes melanoma samples and uses a pentanucleotide substitution model to minimize mutational biases.

(B) Heatmap depicting the fraction of mutations in 288 hypermutator samples (>1,000 mutations/exome) attributed to different mutational signatures (Alexandrov et al., 2013).

(C) Left: dN/dS ratios (trinucleotide model) for each class of hypermutators. Right: dN/dS ratios from a neutral simulated dataset of POLE mutations. This neutral dataset was generated by randomizing all non-coding substitutions from five POLE hypermutator whole-genomes to a different site with an identical 9-nucleotide context, within 1-megabase of its original position.

(D) Stacked bar plot showing the frequency of each base around C > A and C > T substitutions in POLE hypermutator tumors.

(E–G) Conservative estimation of the fraction (F) and absolute number (G) of driver coding substitutions in known cancer genes. To obtain these estimates, dN/dS ratios for known cancer genes were normalized by those from putative passenger genes, to conservatively remove mutational biases from dN/dS. Application of this approach to our tissue-specific estimates in Figure 4A yields analogous results (E).