Abstract

After 20 years of steady increase, kiwifruit industry faced a severe arrest due to the pandemic spread of the bacterial canker, caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae (Psa). The bacterium penetrates the host plant primarily via natural openings or wounds, and its spread is mainly mediated by atmospheric events and cultural activities. Since the role of sucking insects as vectors of bacterial pathogens is widely documented, we investigated the ability of Metcalfa pruinosa Say (1830), one of the most common kiwifruit pests, to transmit Psa to healthy plants in laboratory conditions. Psa could be isolated both from insects feeding over experimentally inoculated plants, and from insects captured in Psa-infected orchards. Furthermore, insects were able to transmit Psa from experimentally inoculated plants to healthy ones. In conclusion, the control of M. pruinosa is recommended in the framework of protection strategies against Psa.

Keywords: bacterial canker of kiwifruit, insect-mediated disease transmission, microscopical visualization

Over the past 20 years, the worldwide cultivation of kiwifruit has remarkably increased. Italy is the second largest kiwifruit producer after China, with a production of 507,000 tons in 2014, corresponding to 15% of the global production (FAO, 2017). However, yields and cultivation acreages of kiwifruit have been severely reduced due to the pandemic spread of bacterial canker of kiwifruit since 2008 (Vanneste et al., 2011). The disease is caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae (Psa), a rod-shaped, Gram-negative, strictly aerobic and mobile bacterium (Takikawa et al., 1989), which affects both Actinidia chinensis and A. deliciosa (Donati et al., 2014). Psa penetrates host tissues through wounds or natural openings, such as stomata or lenticels (Spinelli et al., 2011). Once inside the apoplast, it is able to move in the plant vascular system, spreading systemically, and eventually leads to plant death. Psa spreads by rain, wind, insects, animals and agricultural activities (Vanneste et al., 2011).

Many cases of insect transmission have been studied so far, regarding fungi, bacteria, viruses and phytoplasmas. The pathogens may be transmitted accidentally by insect vectors, or, in some cases, develop a close symbiotic relationship that contributes to their spread, by enhancing bacterial viability or growth in the vectors, or their target specificity. It was estimated that 30–40% of the damage and yield were due to the direct or indirect effects of pathogens transmission by insects (Agrios, 2008). Insects can transmit pathogens over long distances from one cultivating area to the other ones (Brown et al., 2002). Metcalfa pruinosa Say (1830) (Hemiptera: Flatidae) is considered a very important invasive species in Europe, due to its highly gregarious behavior, motility and multiplication rates, and to its wide range of host plants, including Actinidia spp. (Grozea et al., 2011). After its accidental introduction to Europe from North America (Wilson and McPherson, 1981), the insect has become widespread due to its polyphagia and the absence of natural enemies (Grozea et al., 2015). M. pruinosa has a univoltine life cycle (i. e., it reproduces once per year), with wintering in the egg stage. Eggs are deposited in the bark crevices starting from August. Hatching takes place in May–July, and the insect completes its life cycle on the plants by late summer (Tremblay and Priore, 1994; Zangheri and Donadini, 1980). M. pruinosa feeds by sucking plant saps at all post-embryonic stages. Pre-adult forms (neanids) differ from adults for the absence of wings, and preferably feed on the undersides of the leaves. Nymphs move from the leaves to the new branches and then return on the leaves for metamorphosis. M. pruinosa can contribute to spread a number of plant pathogens (Strauss, 2010). Besides, it produces a substantial amount of honeydew that may represent a growing substrate for bacterial pathogens and may also attract bees. Therefore, the latter may act as secondary vectors of the bacterial pathogen further increasing the disease pressure inside the orchard.

This study investigated the possible role of M. pruinosa to transmit Psa in controlled conditions.

Materials and Methods

Biological material

In all the experiments, the Psa strain CFBP7286-GFPuv was used. This genetically engineered strain retains the virulence features of the wild type, is resistant to kanamycin, and expresses a green fluorescent protein facilitating its recognition and observation under UV light (Spinelli et al., 2011). The titer of bacterial suspensions was determined by plating 10 μl drops of serial 1:10 dilutions on Luria-Bertani agar medium amended with cyclohexamide (100 mg l−1) and kanamycin (100 mg l−1).

Eight- to ten-month-old seedlings (approx. 30 cm high) derived from A. deliciosa cv. Hayward were used as the host plants. During the experiments, the plants were kept at 22°C, 70% RH and a light-dark cycle of 16:8 h of natural light.

M. pruinosa insects for laboratory experiments were captured from a kiwifruit orchard located near Bologna, Italy (44°33′00.72″N; 11°23′07.67″E). When not stated otherwise, the experiments were replicated in two consecutive seasons (2013–2014) from mid-May to early June.

Psa population on field-captured insect samples

Insects were captured from a kiwifruit orchard located near Faenza (Italy) in mid-June (juvenile stages) and at the end of July (adults). The percentage of insects contaminated with Psa was assessed by direct isolation and enumeration. The insects were singularly placed in tubes containing 5 mL of 10 mM MgSO4 and washed for 20 minutes under agitation. The bacterial population was determined in the wash. The results of direct isolation were further confirmed by qPCR (Pushparajah et al., 2014) on 10 individuals per class, using primers F1 and R2 as described by Rees-George et al (2010).

Artificial feeding of M. pruinosa

The method was adapted from Tanne et al (2001). A sterilized feeding solution (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8, amended with 50 g l−1 sucrose) was inoculated with Psa to a titre of 3 × 108 colony-forming units (cfu) ml−1. Bacterial survival in the feeding solution was checked for 96 h.

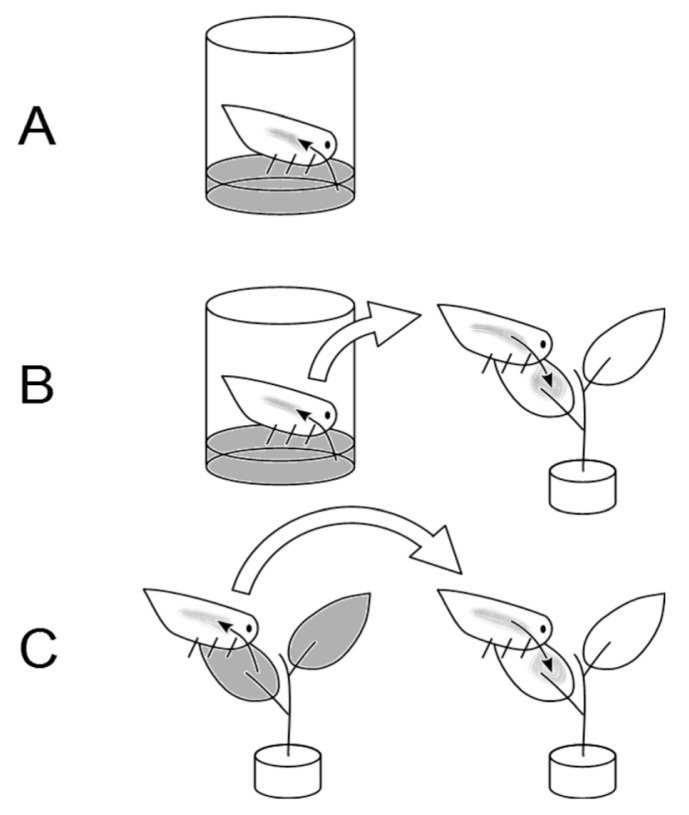

Insect chambers were made with 15 ml transparent tubes with their bottom side cut; the resulting opening was wrapped with anti-aphid net to allow gas exchange. After autoclave sterilization of the tube, 1 ml feeding solution was placed in the internal volume of the cap, and sealed with a layer of Parafilm to prevent the direct contact between the insect and the feeding solution. On the outer side of the cap, a green film was placed to mimic the foliar surface and attract the insect for feeding (Fig. 1A). Each tube contained one adult or one juvenile individual of M. pruinosa and a total of 50 insects were used for these experiments. The tubes were incubated at 22°C, 70% RH under light-dark cycle of 16:8 h. The insects were kept in the feeding tubes for 2, 4, 5, 6 or 9 days. Immediately after the feeding period, each insect was individually frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis. Psa incidence and population were determined in the homogenate obtained from 12–20 insects per time point, by plating tenfold successive dilutions on agarized medium.

Fig. 1.

Experiment set up: (A) Artificial feeding of Metcalfa pruinosa. Individual insects, closed in an isolated chamber, feed on a Psa-inoculated solution (in grey). The population of Psa in the insect is subsequently determined. (B) Transmission of Psa from M. pruinosa adults, fed with a medium containing the bacterium, and subsequently transferred on healthy kiwifruit leaves. (C) Transmission of Psa from M. pruinosa adults, fed on experimentally inoculated kiwifruit plants, and subsequently transferred on healthy ones.

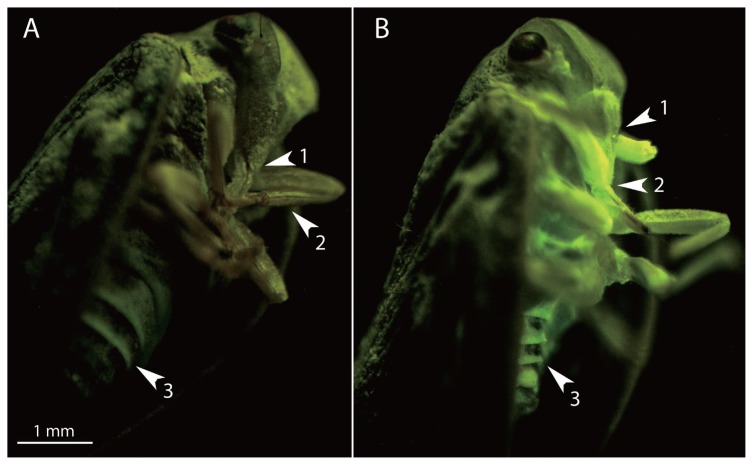

Microscopic visualization of Psa on Metcalfa pruinosa

A sample of three insects, including adults and nymphs, was taken from the artificial feeding experiment on day 2, 4 and 5. The insects were dipped in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. After two weeks, they were sectioned longitudinally and observed under a binocular microscope to verify the presence of the fluorescent bacterium under a UV source (excitation wavelength of GFP-B: 460–500 nm, emission wavelength: 510–560 nm). These analyses were performed using a Nikon SMZ25 fluorescence microscope (Nikon Instruments Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), with an optical system provides zoom ratio of 25:1 (zoom range 0.63 × – 15.75 ×), LED DIA light intensity control and epifluorescence filter cube selection.

Transmission of Psa by M. pruinosa

The first phase of this experiment (Fig. 1B) was a one-run explorative test of the ability of M. pruinosa fed on a Psa-containing medium to transmit the disease to healthy plants. Adult insects were artificially fed for 7 days as previously described, with an extract of A. deliciosa cv. Hayward leaves (30 g l−1 fresh tissue in 10 mM MgSO4) containing 106 cfu ml−1 Psa. After the artificial feeding, each insect was individually transferred in a chamber (3 cm diameter, 2 cm length, closed on one side with anti-aphid net) fixed on the adaxial surface of the healthy host plant leaves. The insects were kept in the chamber for 2 weeks, and the leaves were collected 4 weeks after the insect transfer, to allow the development of primary symptoms (leaf spots). The exposed leaf and the insects were surface sterilized by sequential washing in ethanol (70%), in NaClO (1%) and twice in sterile water, then they were ground in 5 and 1.5 ml, respectively, of sterile 10 mM MgSO4. The homogenate was used for the determination of bacterial populations by direct re-isolation plus plate enumeration and by qPCR (from plant tissues) as described above.

In the second step (Fig. 1C), it was tested whether insects feeding on diseased plants can spread the pathogen to healthy ones. Twelve plants were infected by spray inoculation with a Psa suspension (4.2 × 105 cfu ml−1). Two days after inoculation, 6 adults of M. pruinosa were placed on each plant and allowed to feed on it for 7 days. Thereafter, each group of 6 insects was transferred on one of 15 healthy plants and allowed to feed on it for 7 days. On these plants, symptom development was monitored over 30 days. Psa population was quantified, as previously described, on experimentally inoculated plants (1 week after inoculation), in the insects (after 14 days of feeding on non-inoculated plants) and in the plants receiving the vector insects (30 days after the transfer of infected insects).

Statistical analysis

Significance of correlations was assessed with Fisher’s exact test, assuming a confidence level of 0.05. ANOVA and Fisher’s LSD test were used to assess significance of differences in bacterial populations in insects according to feeding time (P < 0.05). The STATISTICA ver. 5 software (StatSoft Inc, Tulsa, USA) was used for calculation.

Results

Contamination of M. pruinosa by artificial feeding

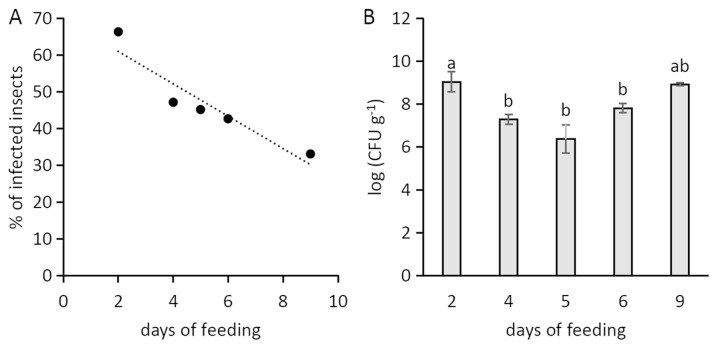

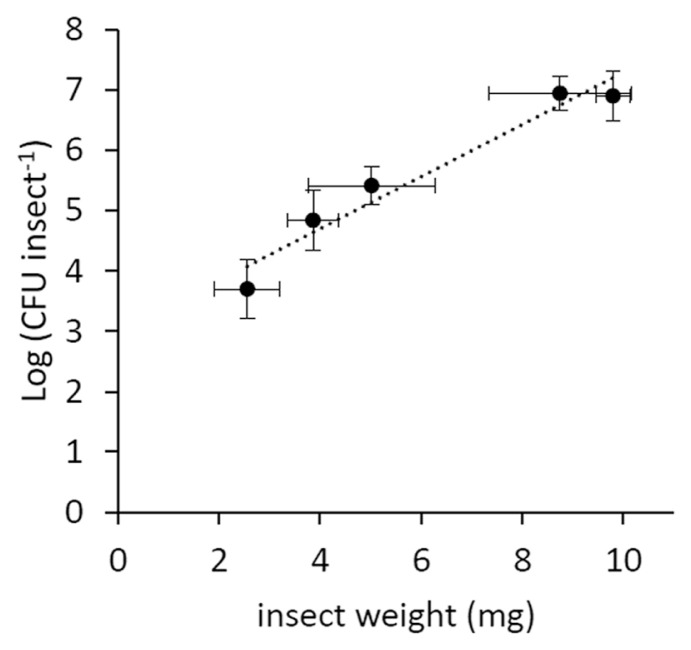

Psa showed a limited survival in the artificial feeding solution, as no viable bacteria were found after 24 h from inoculation. In the artificial feeding experiments, the percentage of infected insects reached 67%, but it negatively correlated with the duration of artificial feeding (Fig. 2A). The infected individuals hosted a Psa population decreasing over time (Fig. 2B). However, the bacterial population associated to infected insects positively correlated with their weight (Fig. 3). The percentage of infected neanids (33%) was lower than the one of adults (49%).

Fig. 2.

(A) Percentage of infected insects in relation to artificial feeding time. The correlation was significant according to Fisher’s exact test. (B) Population of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae in the contaminated insects, expressed according to the days of artificial feeding. The data refer to 12–20 individual insects per each sampling point (A) and to those positive for Psa among them (B) in the 2013 and 2014 artificial feeding experiments. Bars with different letters are significantly different according to Fisher’s LSD test (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Bacterial load in relation to insect weight. Data refer to average values with standard errors of contaminated insects (5–9 per point) taken at the same sampling times in the 2013 and 2014 artificial feeding experiments. The correlation is significant according to Fisher’s exact test (P < 0.05).

Psa colonization of insect tissues

The localization of Psa on M. pruinosa by microscopical observation showed a bacterial contamination on the mouth parts, legs and the abdominal metameres (Fig. 4). Insects sections showed that the bacteria concentrated also in the inner parts of the mouth and abdomen showing the spread of the pathogen in the digestive apparatus.

Fig. 4.

Fluorescence steromicroscopy photographs of healthy (A) or contaminated (B) Metcalfa pruinosa adult individuals. Bright green fluorescent emission is due to Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae (CFBP7286-GFPuv) colonization of tissues (1: mouthparts, 2: limbs and 3: urosternites). Insects were contaminated by feeding on artificial medium containing the GFPuv-labelled pathogen. Photographs were taken after 4 days of feeding.

Field incidence and population of Psa in M. pruinosa

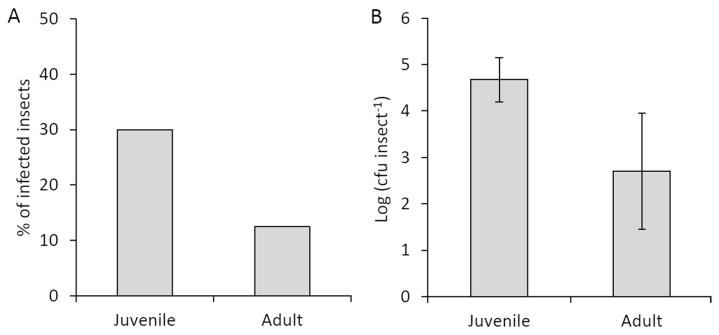

In contrast with in vitro experiments, field-collected juvenile insects showed a higher incidence of Psa compared to adults (30% and 13%, respectively; Fig. 5A). The average bacterial population was also higher on neanids (1.5 × 105 cfu/insect) than on adults (5.0 × 102 cfu/insect) (Fig. 5B). Data obtained by qPCR were compatible with plate enumeration of colonies (Supplementary Table 1). About half of the insects feeding on experimentally infected plants resulted contaminated with Psa. The insects harbored a Psa population, which did not correlate with the pathogen population inside the plants where the insect fed (Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Presence of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae in Metcalfa pruinosa 2014 field captures. Insects (24 for each class) were captured from a kiwifruit orchard located near Faenza (Italy) in mid-June (juveniles) and at the end of July (adults). (A) percentages of infected insects. (B) Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae population per insect. Standard error is shown.

Table 1.

Population of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae in the experimentally infected plants, in the vector insects and in the non-inoculated plants after vector insect feeding

| Experimentally infected plants (cfu g−1) | Insects (cfu g−1) | % of infected insects | Non-inoculated, recipient plants (cfu g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (7.3 ± 1.3) × 104 | (7.7 ± 0.9) × 106 | 33 | (1.2 ± 0.3) × 103 |

| (8.9 ± 0.0) × 106 | 5 | (5.0 ± 2.9) × 102 | |

| (1.2 ± 0.3) × 105 | (6.7 ± 2.2) × 106 | 17 | Not detected |

| (6.9 ± 2.7) × 106 | 5 | (5.5 ± 0.5) × 103 | |

| (6.8 ± 0.9) × 104 | (7.8 ± 0.8) × 106 | 83 | (5.3 ± 1.4) × 104 |

| (4.5 ± 0.0) × 106 | 33 | (3.0 ± 1.5) × 103 | |

| (6.5 ± 1.2) × 105 | (4.8 ± 4.5) × 106 | 17 | (2.0 ± 2.0) × 102 |

| (8.0 ± 1.5) × 105 | (9.2 ± 8.5) × 106 | 17 | Not detected |

| (9.0 ± 1.0) × 104 | (7.2 ± 1.2) × 106 | 67 | (1.5 ± 1.2) × 103 |

| (7.3 ± 0.9) × 104 | (9.1 ± 0.1) × 106 | 33 | (7.3 ± 0.5) × 104 |

| (5.0 ± 1.1) × 105 | (7.3 ± 0.9) × 106 | 83 | (1.0 ± 0.7) × 104 |

| (9.3 ± 0.5) × 105 | (8.7 ± 0.4) × 106 | 33 | (1.8 ± 0.8) × 105 |

| (1.2 ± 0.1) × 106 | (8.9 ± 7.2) × 106 | 17 | (1.5 ± 0.9) × 103 |

| (3.0 ± 0.4) × 106 | (7.5 ± 1.1) × 106 | 83 | (3.7 ± 2.2) × 103 |

| (2.0 ± 0.4) × 106 | (6.6 ± 2.3) × 106 | 67 | (3.0 ± 0.7) × 104 |

Psa transmission mediated by M. pruinosa

M. pruinosa adults fed on inoculated plant extract were able to transfer the bacterium to 5 out of 15 plants and, one month after the insect-mediated disease infection, the plants harbored an average of 2.9 × 102 cfu g−1 of plant fresh weight.

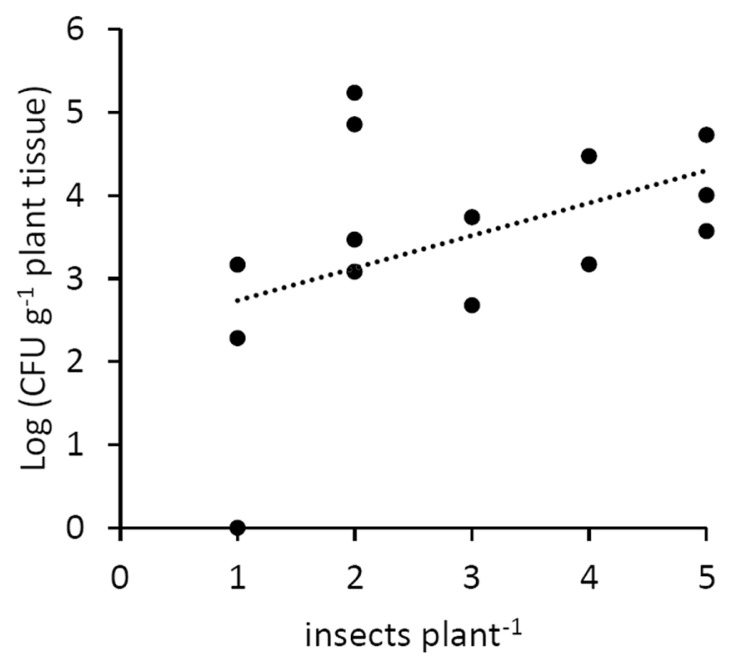

The insects feeding on infected plants were able to transmit the disease to 13 healthy plants out of 15 (Table 1, Supplementary Table 2). A positive correlation was also noted between the number of infected vector insects feeding on a single acceptor plant, and the bacterial titre in the same plant (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Population of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae in host plants, in relation to the number of vector insects feeding on them. The correlation is significant according to Fisher’s exact test with a confidence level of 0.05.

Discussion

Efficiency of M. pruinosa-mediated Psa spread

Psa was found in nearly half of the insect samples, either feeding on artificial medium or experimentally inoculated plants. The quantification of Psa inside the insect and the microscopical visualization confirmed the bacterium presence in the insect’s digestive apparatus. In addition, the pathogen can be transmitted by contaminated insects to healthy plants. All together, these data demonstrate that the insects could vector the bacterium from plant to plant. However, the number of infected insects feeding on a plant, rather than their bacterial load, is determinant for the disease transmission. Therefore, low transmission efficiency may be hypothesized from M. pruinosa, while a high number of feeding events would increase the chance of infection. This is particularly important in the light of M. pruinosa’s gregarious behavior.

The negative correlation between infected insect percentage and days of feedings (Fig. 2B) may be due to the low viability of the bacteria in artificial solution or to the activity of insect immune system (Vilmos and Kuruoz, 1998), which may produce several antimicrobial compounds, as shown for bees (Gätschenbergar et al., 2013). On the other hand, the apparent increase observed after 9 days of feeding is possibly linked to the insect’s growth in weight, which positively correlates with the bacterial population hosted by the vector (Fig. 3).

Ecological factors related to Psa spread

Specific features of bacterial strains and environmental conditions may influence several aspects of the vector-pathogen-host interaction, by affecting pathogen multiplication in source hosts, pathogen multiplication within vectors (Feil and Purcell 2001), vector behaviour (Su and Mulla, 2001), or movement (Vail and Smith, 2002). Notably, the transmission of Psa via puncturing insects is not influenced by the number and status of generally acknowledged infection routes, such as stomata, flowers and wounds, and may be overlooked by common orchard protection measures. One of the symptoms of the bacterial canker of kiwifruit consists in droplets or masses of sticky exudate (ooze) on the surface of host tissues (Donati et al., 2014) which could stick on the limbs and bodies of visiting insects. In natural conditions, the sugars in the bacterial exudate may attract M. pruinosa and other insects as a food source, making them possible vectors of the bacteria contained in the same exudates (Agrios, 2008). In addition, M. pruinosa itself produces a sugary honeydew that may smear the plant surface and attract other insects. If Psa could be detected in this secretion, it may contribute further to Psa dispersion. Besides its feeding behavior, M. pruinosa could carry pathogens externally on their bodies after the contact with infected plant tissue or bacterial ooze (Fig. 5B). Oviposition is another crucial stage in the biological cycle of M. pruinosa, consisting in the mechanical injection of the eggs in host tissues. Since oviposition takes place from September to October, when the weather conditions are still favorable for the development of the bacterial canker, it may significantly contribute to the spread of Psa.

Insect developmental stage and vectoring ability

The insects’ developmental phase may affect their immune system efficiency, with juvenile stages more exposed to bacterial contamination (Gätschenbergar et al., 2013). In contrast, previous studies on several leafhopper species suggested that vector age did not influence their vectoring capacity (Chiykowski and Sinha 1988; Murral et al., 1996), or that slight differences were due to the amount of sap ingested (Palermo et al., 2001). In this work, field and laboratory observations yielded contrasting evidence on Psa incidence in relation to developmental stage. Thus, environmental conditions, such as temperature (Murral et al., 1996), water availability, and their effects on Psa and host plants, rather than insect physiology, may be responsible for the observed differences.

Applicative remark

The ecological importance of M. pruinosa as a vector of Psa in field conditions has not yet been evaluated. In particular, the production of infected honeydew, the attraction of M. pruinosa by bacterial exudates and the survival of the pathogen inside and outside M. pruinosa in different climatic conditions require further research. However, our results demonstrated the capacity of M. pruinosa to vector the disease in controlled conditions. Thus, the control of M. pruinosa and, possibly, other pests is suggested to minimize the risk of Psa diffusion.

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

The work was funded by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no 613678 (DroPSA - Strategies to develop effective, innovative and practical approaches to protect major european fruit crops from pests and pathogens). This research is a part of dr. Sofia Mauri’s PhD thesis.

References

- Agrios GN. Transmission of plant disease by insects. In: Capinera JL, editor. Encyclopedia of entomology. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2008. pp. 2290–2317. [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Lynch L, Zilberman D. The economics of controlling insect-transmitted plant diseases. Am J Agric Econ. 2002;84:279–291. doi: 10.1111/1467-8276.00297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiykowski LN, Sinha RC. Some factors affecting the transmission of eastern peach X-mycoplasmalike organism by the leafhopper Paraphlepsius irroratus. Can J Plant Pathol. 1988;10:85–92. doi: 10.1080/07060668809501738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donati I, Buriani G, Cellini A, Mauri S, Costa G, Spinelli F. New insights on the bacterial canker of kiwifruit (Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae) J Berry Res. 2014;4:53–67. doi: 10.3233/JBR-140073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FAO. [30 March 2017];FAOStat data on world kiwifruit production. URL http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC/

- Feil H, Purcell AH. Temperature-dependent growth and survival of Xylella fastidiosa in vitro and in potted grapevines. Plant Dis. 2001;85:1230–1234. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2001.85.12.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gätschenbergar H, Azzami K, Tautz J, Beier H. Antibacterial immune competence of honey bees (Apis mellifera) is adapted to different life stages and environmental risks. PLos One. 2013;8:e66415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grozea I, Gogan A, Virteiu AM, Grozea A, Stef R, Molnar L, Carabet A, Dinnesen S. Metcalfa pruinosa Say (Insecta: Homoptera: Flatidae): a new pest in Romania. Afr J Agric Res. 2011;6:5870–5877. [Google Scholar]

- Grozea I, Vlad M, Virteiu AM, Stef R, Carabet A, Molnar L, Mazare V. Biological control of invasive species Metcalfa pruinosa Say (Insecta: Hemiptera: Flatidae) in ornamentals plants by using Coccinelids. J Biotechnol. 2015;208:S5–S120. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.06.352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murral DJ, Nault LR, Hoy CW, Madden LV, Miller SA. Effects of temperature and vector age on transmission of two Ohio strains of aster yellows phytoplasma by the aster leafhopper (Homoptera: Cicadellidae) J Econ Entomol. 1996;89:1223–1232. doi: 10.1093/jee/89.5.1223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo S, Arzone A, Bosco D. Vector-pathogen-host plant relationships of chrysanthemum yellows (CY) phytoplasma and the vector leafhoppers Macrosteles quadripunctulatus and Euscelidius variegatus. Entomol Exp Appl. 2001;99:347–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1570-7458.2001.00834.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pushparajah IPS, Ryan TR, Hawes LG, Smith BN, Follas GB, Rees-George J, Everett KR. Using qPCR to monitor populations of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae on kiwifruit vines after spray application of Bacstar™. N Z Plant Prot. 2014;67:220–225. [Google Scholar]

- Rees-George J, Vanneste JL, Cornish DA, Pushparajah IPS, Yu J, Templeton MD, Everett KR. Detection of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers based on the 16S–23S rDNA intertranscribed spacer region and comparison with PCR primers based on other gene regions. Plant Pathol. 2010;59:453–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02259.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli F, Donati I, Vanneste JL, Costa M, Costa G. Real time monitoring of the interactions between Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae and Actinidia species. Acta Hortic. 2011;913:461–465. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2011.913.61. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss G. Pest risk analysis of Metcalfa pruinosa in Austria. J Pest Sci. 2010;83:381–390. doi: 10.1007/s10340-010-0308-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su T, Mulla MS. Effects of temperature on development, mortality, mating and blood feeding behavior of Culiseta incidens (Diptera: Culicidae) J Vector Ecol. 2001;26:83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takikawa Y, Serizawa S, Ichikawa T, Tsuyumu S, Goto M. Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae pv. nov.: the causal bacterium of canker of kiwifruit in Japan. Ann Phytopath Soc Japan. 1989;55:437–444. doi: 10.3186/jjphytopath.55.437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanne E, Boudon-Padieu E, Clair D, Davidovich M, Melamed S, Klein M. Detection of phytoplasma by polymerase chain reaction of insect feeding medium and its use in determining vectoring ability. Phytopathology. 2001;91:741–746. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2001.91.8.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay E, Priore R. Metcalfa pruinosa arrived to Campania. L’Informatore Agrario. 1994;50:69–71. (in Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Vail SG, Smith G. Vertical movement and posture of blacklegged Metcalfa pruinosa arrived to CampaniaMetcalfa pruinosa arrived to CampaniaMetcalfa pruinosa arrived to CampaniaMetcalfa pruinosa arrived to CampaniaMetcalfa pruinosa arrived to Campaniatick (Acari: Ixodidae) nymphs as a function of temperature and relative humidity in laboratory experiments. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:842–846. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-39.6.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanneste JL, Kay C, Onorato R, Yu J, Cornish DA, Spinelli F, Max S. Recent advances in the characterisation and control of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae, the causal agent of bacterial canker on kiwifruit. Acta Hortic. 2011;913:443–455. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2011.913.59. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vilmos P, Kuruoz E. Insect immunity: evolutionary roots of the mammalian innate immune system. Immunol Lett. 1998;62:59–66. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2478(98)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SW, McPherson JE. Life histories of Anormenis septentrionalis, Metcalfa pruinosa, and Ormenoides venusta with descriptions of immature stages. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1981;74:299–311. doi: 10.1093/aesa/74.3.299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zangheri S, Donadini P. Appearance in Veneto of a neartic homopteran: Metcalfa Pruinosa Say (Homoptera, Flatidae) Redia. 1980;63:301–305. (in Italian) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.