Although the incidence of mitral stenosis has declined precipitously in the Western world due to the reduced incidence of rheumatic heart disease, mitral regurgitation remains one of the most common valvular pathologies.1 Many patients affected by severe mitral valve disease are elderly with multiple comorbidities and are at high risk for traditional open surgical mitral valve repair or replacement. The emergence of minimally invasive strategies for the treatment of mitral regurgitation, such as placement of a percutaneous edge‐to‐edge device (MitralClip, Abbott, Santa Clara, CA) to help improve the severity of mitral regurgitation has proven a successful alternative to open surgery in selected patients.2 This technique, however, is not possible in every patient because of anatomic limitations.

Another important patient group that can be high risk for operative intervention includes those with degenerative prosthetic mitral valves or annuloplasty rings. The major cause of bioprosthetic mitral valve dysfunction is cusp calcification causing leaflet thickening and stiffening, which can result in valve stenosis with or without concomitant regurgitation related to leaflet tears. Prosthetic valve dysfunction can also result from extensive tissue overgrowth, thrombus, and the development of a paravalvular leak. The 15‐year reintervention rate for bioprosthetic mitral valves is ≈40%,3 but the mortality rate for surgical bioprosthetic valve rereplacement ranges from 3% to 23%,4 which is not appropriate for high‐risk patients with multiple comorbidities.

The recent success of transcatheter aortic valve replacement has led to interest in extending this technique to the mitral valve. There are several transcatheter mitral valves in early development, and clinically there have been multiple reports describing the transcatheter implantation of replacement valves in the mitral position among patients with severe mitral annular calcification, mitral annular rings, or bioprosthetic mitral valves.5, 6

The emergence of transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR) as a distinct procedure presents a unique challenge to clinicians. The complex anatomy of the mitral valve annulus and its proximity to the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) make preprocedural evaluation crucial. There is an important need to understand the 3‐dimensional (3D) relationship between the aortic and mitral valves in order to select an appropriately sized valve and predict whether TMVR will result in obstruction of the left ventricular outflow track from the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve. In this article we provide an overview of how to use cardiac computed tomography (CT) to project neo‐LVOT measurements pre‐TMVR and illustrate how this technique has performed across a series of clinical cases.

Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Anatomy

The LVOT is the region of the left ventricle (LV) that lies between the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve posteriorly and the interventricular septum anteriorly.7 It is a conduit between the lumen of the LV inferiorly and the aortic valve leaflets superiorly, although there is no clear anatomic demarcation between the LVOT and the LV cavity. In normal anatomy the LVOT lies at an approximate angle of 45° from the median plane and is directly posterior to the right ventricular outflow tract. Its anterior wall consists of both the membranous and muscular parts of the interventricular septum. The atrioventricular node typically lies at the junction between these two components of the interventricular septum. The LVOT posterior wall is formed by the fusion of the anterior and posterior mitral cusps, the intervalvular fibrosa, and the mitral valve anterior leaflet from superior to inferior. The intervalvular fibrosa is a fibrous structure that lies at the junction of the anterior mitral valve leaflet and the noncoronary cusp of the aortic valve and is the basis of fibrous skeleton of the heart.8 The LVOT lumen is predominantly oval in shape, but is dynamic and changes in both size and shape throughout the cardiac cycle. It appears more circular during systole, but has a wider transverse than anteroposterior diameter throughout the cardiac cycle.9

Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction

Obstruction of the LVOT can be either fixed or dynamic. Fixed obstruction can be caused by a congenital abnormality in the LVOT, such as a subaortic membrane or a fibrous ring. Less frequently, a tumor can also cause LVOT obstruction. The most common cause of dynamic LVOT obstruction is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), occurring in ≈25% of patients.10 The mechanism of LVOT obstruction in HCM usually involves anterior motion of the mitral valve during systole causing mitral‐septal contact by the leading edge of the anterior mitral leaflet.11 LVOT obstruction in HCM or hypertensive cardiomyopathy can also be caused by septal hypertrophy in the absence of systolic anterior movement, although this is less common. Studies in HCM have identified a consistent link between increased LVOT pressure gradients and cardiovascular events and heart failure symptoms, with a higher probability of death in patients with LVOT obstruction.10, 12 Severe LVOT obstruction can cause syncope due to cerebral hypoperfusion and can lead to ventricular arrhythmias. Another consequence of LVOT obstruction is the redirection of LV stroke volume toward the mitral valve, resulting in mitral regurgitation.

There is a risk of LVOT obstruction secondary to systolic anterior movement of ≈4% following repair of a myxomatous regurgitant mitral valve due to excess leaflet tissue.13 LVOT obstruction is a rarer complication of surgical mitral valve replacement; its true incidence is difficult to evaluate, but it is likely less than 1%.14, 15, 16 This can result from improper orientation of a bioprosthetic mitral valve strut, from imposition of a large valve strut into a small LVOT, or from a mechanical valve prosthesis having been sutured low to a preserved residual mitral valve leaflet.17, 18 During systole the prosthesis is then free to move anteriorly and can obstruct the LVOT.16 Because TMVR involves placement of an in‐situ valve prosthesis, it can potentially cause LVOT obstruction by pushing the native anterior mitral leaflet or bioprosthetic leaflet into the LVOT. Although there is limited data thus far on the incidence of LVOT obstruction post TMVR, initial data suggest a rate of acute LVOT obstruction of ≈7% to 9%,19 with higher rates occurring in patients with severe mitral annular calcification20, or in those undergoing valve‐in‐valve or valve‐in‐ring procedures.21 Reduction in the LVOT cross‐sectional area is one of the principal causes of LVOT obstruction observed in HCM.22 Bapat et al studied the factors that influence LVOT obstruction in transcatheter mitral valve implantation.23 The authors concluded that the degree of incursion of the prosthetic mitral valve into the LVOT was the main factor in predicting obstruction.

The size of the native LVOT and the angle between the aortic and mitral annular planes are associated with an increased risk for obstruction. The aortomitral angle, determined by measuring the interior angle created by the intersection of a virtual plane drawn through the mitral and aortic annuli, is associated with a higher chance of LVOT obstruction as this angle becomes more acute. With the use of modern postprocessing software used in cardiac CT, one can predict the size of the neo‐LVOT by simulating the 3D interactions between the “best‐fit” prosthetic valve and the native valves. In turn, the size of the neo‐LVOT can be used to estimate the risk of LVOT obstruction after TMVR.24, 25 However, it is important to note that the dimensions of the neo‐LVOT are highly dependent on the size of the LV cavity, and thus loading conditions, as well as on the exact location (ie, angle and height) of TMVR implantation.

To determine the size of the neo‐LVOT, we first describe the method by which we project the anticipated 3D anatomical interactions between the prosthetic valve and a given patient's cardiac anatomy.

Cardiac CT Data Acquisition

The cardiac CT protocol for preprocedure TMVR assessment involves performing a gated multiphase cardiac CT with intravenous contrast. Unlike coronary CT angiography studies, β‐blocker or nitroglycerin is not routinely used unless there is a specific request to interrogate the coronary arteries for stenosis. Patients are usually scanned at either 120 or 100 peak kilovoltage depending on size with automated tube current milliampere (mA) modulation. Although the contrast dose varies with the type of scanner, protocol used, and patient size, a dose of 30 to 60 mL is usually sufficient. For a standard patient scanned at 120 kV peak, we recommend using 50 mL of contrast injected at a rate of 4 to 5 mL/s followed by 40 mL of saline. We time the scan acquisition by using a bolus tracking technique, with the region of interest placed in the descending thoracic aorta. In patients with severe renal dysfunction with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, we perform the CT with 30 mL of intravenous contrast. In these low contrast‐dose CTs, image contrast can be improved by reducing the peak kilovoltage, and by injecting the contrast at a higher rate (eg, 5‐6 mL/s). We use prospective ECG gating with acquisition of data from a full R‐R interval for all patients, including those with atrial fibrillation. It is important to acquire images throughout the cardiac cycle, as this allows an assessment of the dynamic changes in the mitral annulus and LVOT. This can be achieved by using either an axial acquisition (for example, with wide‐area detector scanners with complete cardiac coverage in a single gantry rotation) or a helical (for example, with dual‐source scanners, which offer a higher temporal resolution) acquisition with prospective EC gating. Using modern postprocessing software, multiphase data sets can be simultaneously loaded, allowing mitral annular measurements to be performed throughout various phases of the cardiac phase. The mitral annulus typically is larger toward the end of systole at ≈30% to 40% of the R‐R interval in normal individuals, although annular dynamics are affected by disease processes such as ischemic MR or myxomatous degeneration.25, 26 End‐systole is usually the period of the cardiac cycle when the LVOT cross‐sectional area is at its nadir, making this the optimum phase in which to assess for neo‐LVOT obstruction.9 This may or may not be the same phase as when the mitral annulus is at its largest dimension, further underlying the need for having a multiphase acquisition.

Cardiac CT Image Reconstruction

After data acquisition, images from different phases of the cardiac cycle are reconstructed using a typical range of 0% to 95% of the R‐R interval with 5% increments and a slice thickness of 0.5 mm. We use 3D postprocessing software (Vitrea, Vital Images, Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan) to perform mitral annular measurements and to predict the risk of neo‐LVOT obstruction.

Mitral Annulus Assessment Using a 3D Workstation

Native Valve

Accurately measuring annular size in a native mitral valve is crucial in valve sizing for TMVR planning. The prosthetic valve must provide an adequate seal to prevent further valve dysfunction. For example, paravalvular regurgitation may occur if the prosthesis is too small relative to the size of the mitral annulus. Providing these measurements can, however, be challenging. Unlike the aortic valve annulus, the mitral valve annulus is a nonplanar structure and has a saddle shape.27 The anterior peak of this saddle is continuous with the aortic annulus, the posterior peak is the insertion of the posterior mitral valve leaflet, and the nadirs of the saddle are at the level of the medial and lateral fibrous trigones (Figure 1). Because the mitral annulus is nonplanar, accurate measurement for device sizing is challenging. Blanke et al have proposed that the anterior horn of the saddle‐shaped annulus be excluded for TMVR assessment, creating a “D‐shaped” annulus suitable for planar measurements, with the anterior border a virtual line connecting the fibrous trigones.25, 28 One disadvantage of using the D‐shape annulus approach, however, is that it does not always correspond with the shape of the device, which can be circular, depending on the degree of capture at the level of the trigones. Importantly, the entire geometric shape of the device needs to be taken into account in assessing for neo‐LVOT obstruction.

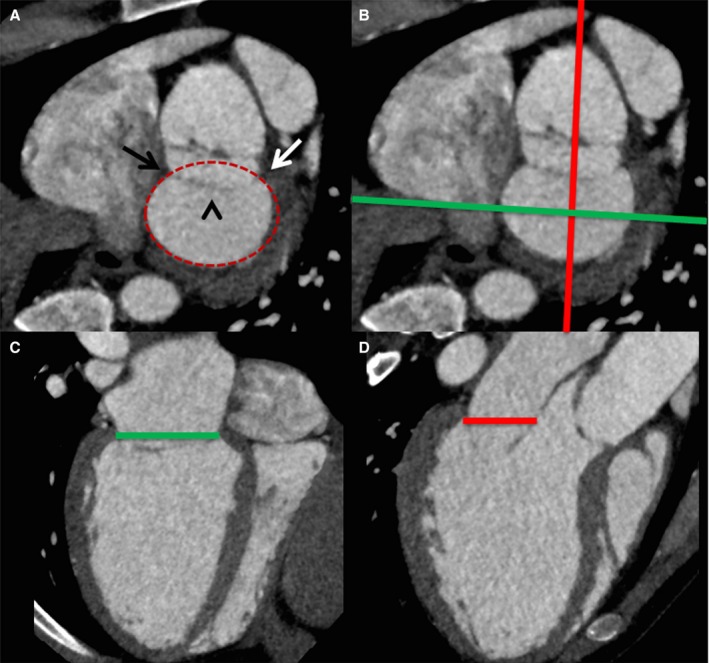

Figure 1.

Performing mitral annular measurements and defining the annular plane on cardiac computerized tomography. A, Short‐axis view of the mitral annular region demonstrates the medial (black arrow) and lateral (white arrow) fibrous trigones, the anterior mitral valve leaflet (arrowhead), with delineation of the annular perimeter (red oval). The green and red lines in (B) demonstrate the orientation of the commissural view in (C) and long‐axis view in (D), with delineation of the mitral annular plane.

The annular plane can be defined by using a combination of short and long axis reformats of the left ventricle, which can identify the insertion points of the mitral valve leaflets (Figure 1). Once the annular plane has been defined, the maximum and minimum annular diameters, annulus area, and perimeter can be measured (Figure 2). By performing these measurements at the maximal annular size, information on prosthesis sizing can be provided, reducing the risk of significant post device implantation paravalvular regurgitation.

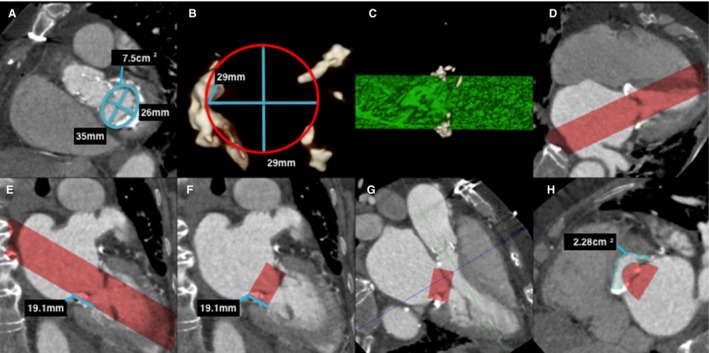

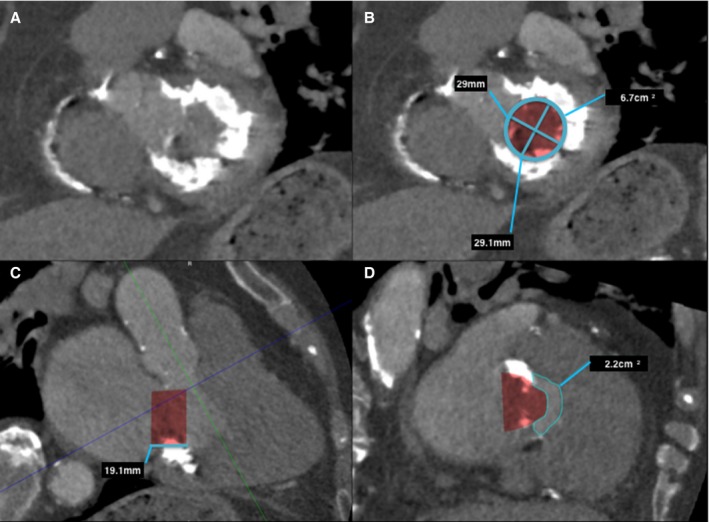

Figure 2.

Predicting neo–left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) area in a native mitral valve on postcontrast cardiac computerized tomography (CT). A, Left ventricle short‐axis multiplanar reformat (MPR) at the level of the mitral annulus demonstrates mitral annulus measurements. Note the mild mitral annular calcification. B, A 3‐dimensional (3D) circular volume‐rendered segmentation (red circle) is performed at the corresponding level of the mitral annulus with the dimensions of the proposed prosthetic valve (in this case a 29‐mm Edwards SAPIEN XT valve). C, This creates a 3D segmented cylindrical volume (green cylinder), viewed here in profile. D, Once segmented, the segmented 3D volume can be projected onto the CT image data, as demonstrated on this 4‐chamber MPR (red volume). E, The proposed prosthetic valve height is then measured (line) and segmented (F) as demonstrated on these 2‐chamber MPRs. G, A 3‐chamber MPR can determine the level of the minimal neo‐LVOT (blue line), and planimetry of the neo‐LVOT can be performed in an orthogonal plane (H).

Valve in Valve and Valve in Ring

The most commonly used method to select a valve size in a patient with an existing prosthetic mitral valve or ring is through the Valve in Valve Mitral smartphone application (UBQO Ltd, London, UK). This application does not, however, address the risk of LVOT obstruction; therefore, obtaining a CT in these cases is important. There is an increased risk of LVOT obstruction in valve‐in‐valve cases, as the old valve can become a cylindrical fixed obstruction after the new valve is placed, and in valve‐in‐ring procedures the new valve can pin the old valve leaflets open, wrapping the anterior mitral leaflet around the new valve, impinging on the LVOT area.23 Limited series thus far have reported combined rates of LVOT obstruction following valve‐in‐valve or valve‐in‐ring procedures of ≈7%, with a higher prevalence in the valve‐in‐ring cases.21 Mitral annulus assessment on CT in the setting of an existing mechanical valve, bioprosthetic valve, or following repair with a mitral ring is often more straightforward than in the case of a native valve (Figures 3 and 4). In such cases the annular plane will be perpendicular to the long axis of the prosthesis, and measurements should be performed between the inner borders of the existing prosthesis, as this is where the new device will sit. When performing measurements of such valves or rings, it is important to use the thinnest possible slices as well as to optimize the display settings to minimize beam hardening. This can be accomplished by using a wide range for the grayscale viewing window. In addition, the use of a higher peak kilovoltage during CT acquisition may also reduce beam‐hardening artifacts.

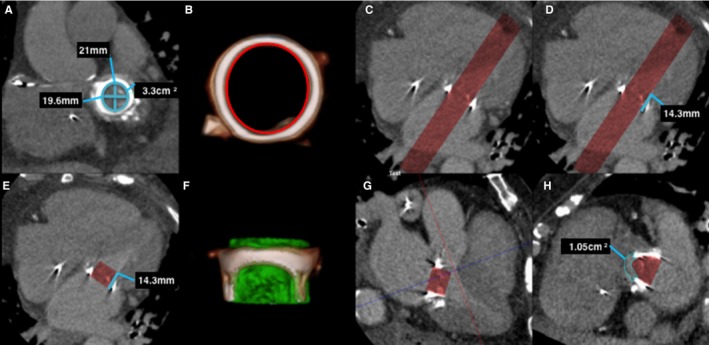

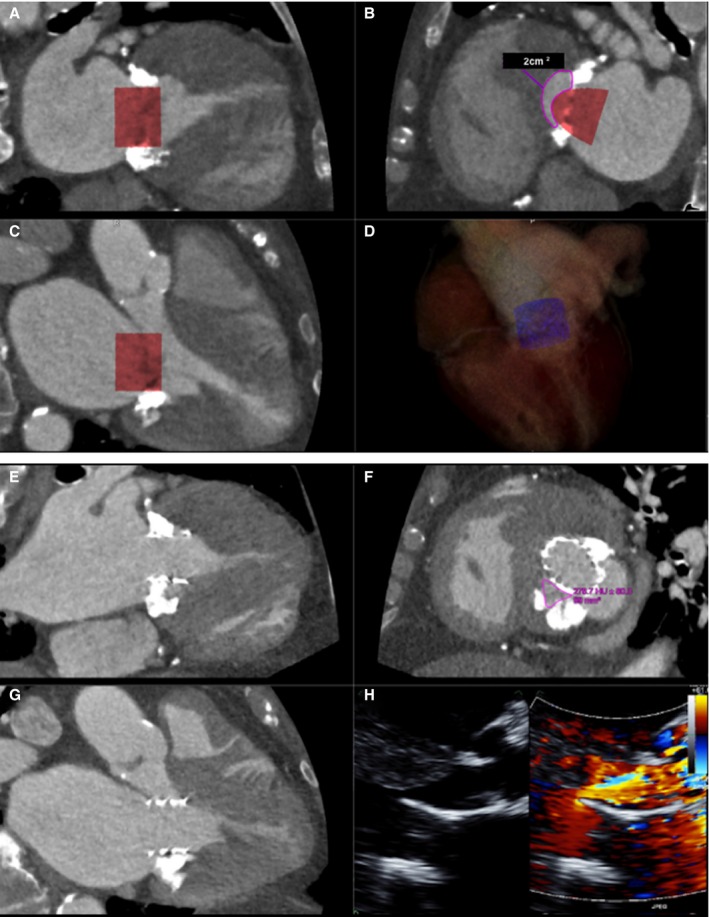

Figure 3.

Predicting neo–left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) area in a prosthetic mitral valve on postcontrast cardiac computerized tomography (CT) using 30 mL iodinated contrast. A, Left ventricle short‐axis multiplanar reformat (MPR) at the level of the mechanical mitral valve demonstrates mitral valve prosthetic measurements. B, A 3‐dimensional (3D) volume segmentation (red circle) is performed of the internal surface of the prosthetic valve at the corresponding level of the mitral annulus with the dimensions of the proposed prosthetic valve (in this case a 23‐mm Edwards SAPIEN XT valve). C, Four‐chamber MPR demonstrates the resulting segmented volume (red volume). D, The valve height (line) is then segmented (E), and 4‐chamber MPR shows the proposed valve prosthesis. F, A 3D segmented volume‐rendered image demonstrates the prosthetic valve volume (green cylinder) in profile inside the existing prosthesis. G, Three‐chamber MPR demonstrates the level of the neo‐LVOT (blue line), with planimetry of the neo‐LVOT performed in an orthogonal plane (H).

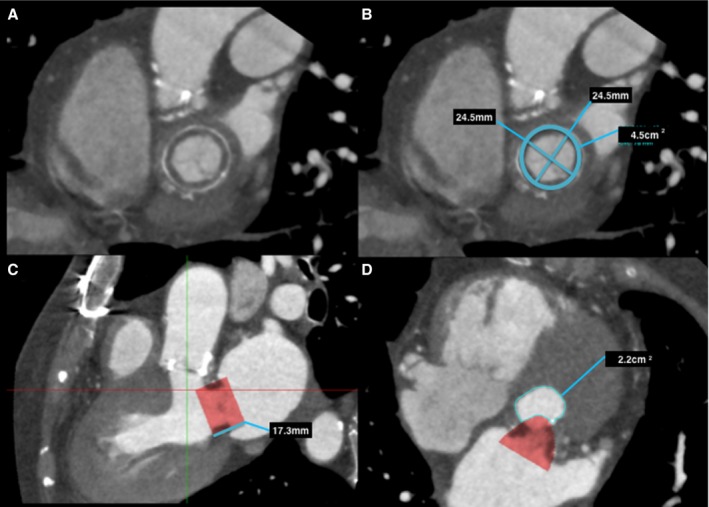

Figure 4.

Predicting neo–left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) area in a bioprosthetic mitral valve on postcontrast cardiac computerized tomography (CT). A, Left ventricle short‐axis multiplanar reformat (MPR) at the level of the bioprosthetic mitral valve, with annotated measurements (B). C, Three‐chamber MPR demonstrates the proposed valve prosthesis, in this case a 26‐mm Edwards SAPIEN XT valve. Planimetry of the neo‐LVOT (C, red line), with planimetry of the neo‐LVOT performed in an orthogonal plane (D).

The annuloplasty rings will have a D‐shape, which may increase the risk of paravalvular leak after transcatheter valve implantation if incomplete sealing occurs. Certain annuloplasty rings are more deformable than others and thus may be more amenable to a transcatheter valve‐in‐ring procedure depending on their flexibility.4

Mitral Annular Calcification

Mitral annular calcification (MAC) is a common degenerative process of the mitral annulus of uncertain clinical significance, with a prevalence of ≈6.1% in the general population.29 Notably, the presence of severe MAC can be helpful for TMVR implantation because it may aid in creating a seal around the new valve thereby reducing paravalvular leak, especially if the MAC is full or near full circumference.20 However, the presence of severe MAC can introduce limitations in viewing and measuring the size of the mitral valve annulus on CT. The use of interactive windowing to create a wide CT viewing window is useful when assessing the mitral annulus in the presence of significant MAC, as this technique can help reduce the deleterious blooming effect from calcium. Conversely, the presence of MAC can aid the 3D segmentation of the mitral annulus when neo‐LVOT assessment is performed in pre‐TMVR CT (outlined below), providing a high‐contrast outline of the annulus (Figure 5). Caseous annular calcification is a rare variant of MAC that can form bulky, masslike calcified lesions along the posterior annulus border, further hindering accurate annular measurement.30, 31

Figure 5.

Predicting neo–left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) area in a native mitral valve with severe mitral annular calcification on postcontrast cardiac computerized tomography (CT) using 30 mL iodinated contrast. A, Left ventricle short‐axis multiplanar reformat (MPR) at the level of the mitral annulus with severe mitral annular calcification, with (B) mitral annular measurements and segmented valve area. Three‐chamber MPR (C) demonstrates the proposed valve prosthesis, in this case a 29‐mm Edwards SAPIEN XT valve. Planimetry of the neo‐LVOT (C, blue line), with planimetry of the neo‐LVOT performed in an orthogonal plane (D).

Neo‐LVOT Assessment

After implantation of a percutaneous mitral valve, there is displacement of the anterior mitral valve leaflet, forming a longer neo‐LVOT. The potential risk of neo‐LVOT obstruction with TMVR can be assessed on a preprocedural cardiac CT by simulating the position and size of the valve prosthesis in the mitral annulus using 3D segmentation techniques available with postprocessing software. The minimal area of the neo‐LVOT can help determine the risk for neo‐LVOT obstruction. The major risk factors for neo‐LVOT obstruction are (1) aortomitral angulation, (2) LV size, (3) interventricular septum size, and (4) device‐related factors.23, 25 The aortomitral angle is the internal angle formed by the intersection of the mitral and aortic annular planes. A parallel orientation is associated with a lower risk of LVOT obstruction, with a perpendicular orientation conferring the highest risk.23 Small LV cavity size is a known risk factor for LVOT obstruction after surgical valve replacement, whereas a larger LV cavity will more easily accommodate a device without impinging on the LVOT.15, 32 As described in the context of HCM, the size of the basal interventricular septum can have an effect on LVOT area, with septal hypertrophy a known cause of LVOT obstruction. The device‐related factors that may impact on potential neo‐LVOT obstruction are protrusion and flaring. Some devices may have an outward flare from the annular to the ventricular portion, which may encroach into the neo‐LVOT, increasing the risk of obstruction. The most important device‐related factor is the degree to which it protrudes into the neo‐LVOT, reducing its cross‐sectional area. This is highly dependent on the height of the device and its site of deployment relative to the mitral annulus.

The valve prosthesis can be projected onto the mitral annulus using 3D segmentation techniques. The cross‐sectional area of the neo‐LVOT can then be measured by planimetry using a multiplanar reformat plane orthogonal to the LVOT centerline (Figures 2, 3, 4 through 5). There are, as yet, no defined neo‐LVOT cross‐sectional area cutoff values to diagnose obstruction definitively. The majority of the available data on LVOT obstruction comes from HCM and aortic stenosis studies. An LVOT area >2.7 cm2 seems to reliably exclude LVOT obstruction in patients with HCM, but values less than this are more difficult to interpret.33 One study in HCM patients found an LVOT area of 2.0 cm2 to be a reliable cutoff between obstructive and nonobstructive HCM,34 with another study finding an association between an LVOT area <0.85 cm2 and a resting pressure gradient >50 mm Hg.35 This heterogeneity is likely due to the significant inter‐individual variation in LVOT area according to body surface area, a phenomenon that has been described on CT in normal individuals.9 Thus, metrics such as neo‐LVOT/aorta area ratio may be potentially useful, taking into account interindividual variation due to body habitus. Vogel‐Claussen et al found in a study of HCM patients that an LVOT/aorta diameter ratio of less than 0.25 was associated with obstructive LVOT pressure gradients.36 Furthermore, in selected cases, when necessary, it is possible to modify the LVOT shape and size using alcohol ablation, which may allow for successful TMVR despite the presence of a small predicted LVOT.37 Prospective studies will be required to determine minimum acceptable neo‐LVOT area in the context of TMVR, but until such results are available, a cutoff of ≤2.0 cm2 appears reasonable in conferring risk of neo‐LVOT obstruction, with an area of <1.5 to 1 cm2 conferring an even higher risk.

Mitral Valve Prostheses

In order to measure the size of the neo‐LVOT, a 3D workstation is first used to create a cylindrical volume that has the dimensions of each potential valve being considered. Before creating the cylindrical volume on CT to simulate the prosthetic valve, it is important to consider its dimensions, especially its height, because this will ultimately determine the predicted neo‐LVOT area. Clinically, TMVR is primarily performed using balloon‐expandable Edwards SAPIEN devices (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA), but several newer devices are coming to market, including dedicated TMVR valves. Although no dedicated TMVR valves are yet approved for routine clinical use,38, 39, 40, 41, 42 transcatheter aortic valve replacement valves are now commonly used for this procedure, and the SAPIEN 3 valve (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA) has recently been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for mitral valve use.43 It is important for the imagers to familiarize themselves with the dimensions of these devices as well as those of the surgically implanted mitral rings and bioprosthetic valves when simulating the cylindrical volume (Table). Although understanding the design, structure, and sizing of potential future novel devices is beyond the scope of this article, we believe that the principles we have covered will be applicable to most valves that are being evaluated. It will still be important to know the dimensions and flow profiles of any novel valves for estimating the risk of LVOT obstruction.

Table 1.

Transcatheter Mitral Valve Characteristics

| Valve | Manufacturer | MV Specific | Commercially Available | Diameter at MA (mm) | Expanded Height (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAPIEN XT | Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA | No | Yes |

23 26 29 |

14.3 17.2 19.1 |

| SAPIEN 3 | Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA | No | Yes |

20 23 26 29 |

15.5 18 20 22.5 |

| LOTUS | Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA | No | Yes |

23 25 27 |

19 19 19 |

| FORTISa | Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA | Yes | No | 29 | N/A |

| CardiAQa | CardiAQ Valve Technologies, Irvine, CA | Yes | No | 40 | N/A |

| Tendynea | Tendyne Inc, Roseville, MN | Yes | No | 30 to 43b | 30 to 50b |

| Tiaraa | Neovasc Inc, Richmond, BC, Canada | Yes | No | 35 | 35 |

| Twelve valvea | Twelve Inc, Menlo Park, CA | Yes | No | N/A | N/A |

| Medtronic mitrala | Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN | Yes | No | N/A | N/A |

| NaviGatea | NaviGate Cardiac Structures, Lake Forest, CA | Yes | No | 30 | 21 |

MA indicates mitral annulus; MV, mitral valve; N/A, not available.

Valves currently enrolled in early feasibility clinical trials. Complete valve dimensions are not yet available.

Adjustable.

Transcatheter Prosthesis Size Selection

To assess the risk of LVOT obstruction, it is important to know what transcatheter prosthesis size the implanter will select, because the degree of LVOT obstruction will be greater with larger‐diameter prostheses owing to their taller stent heights. For valve‐in‐valve procedures, knowledge of the surgical bioprosthesis in place is of paramount importance. If the exact prosthesis is known, then the internal diameter of the prosthesis can be determined, and an appropriate valve size can be selected. For valve‐in‐ring procedures and valve‐in‐MAC procedures, the size of transcatheter prosthesis chosen may be less clear, as it is unlikely that a circular transcatheter prosthesis will fully appose the ring or mitral annulus, and therefore there may be a greater chance of paravalvular regurgitation. The implanter will have to decide between choosing a smaller prosthesis (thereby minimizing risk of LVOT obstruction) but having to potentially treat severe paravalvular regurgitation with percutaneous occlusion of the leaking areas, or choosing a larger prosthesis that may minimize leak but increase risk of LVOT obstruction. Therefore, it is important to model multiple sizes of transcatheter heart valves when assessing the risk of LVOT obstruction. In general, for valve‐in‐valve cases, the valve size is selected based on the true inner diameter of the existing valve, which is the inner dimension of the valve minus the contribution of the valve leaflets after they get pushed up. Consequently, the implantable valve one size up from the true inner diameter is usually selected. The volume of fluid used in the delivery balloon can then be varied to ensure that the valve is flared when deployed.

Valve Simulation to Predict Neo‐LVOT Obstruction

By segmenting a cylindrical volume in the expected position of the prosthetic valve at the mitral annulus, it is possible to predict the minimal cross‐sectional area of the neo‐LVOT. The mitral annular measurement will help in selecting the appropriate valve size. The volume can be segmented according to the diameter and height of the prostheses (Figures 2, 3, 4 through 5). The optimal position of the prosthetic valve in the mitral annulus will depend on the individual design of the particular device used, but in general, the device position should be simulated on the CT images with an atrial‐ventricular ratio of ≈20:80 to 25:75 for native valves, valve‐in‐valve and valve‐in‐ring procedures.24 If the valve is placed with a higher atrial ratio, the risk of valve migration is increased, and the risk of LVOT obstruction is reduced, and vice versa. For valve‐in‐ring cases, it is important to deploy the valve with the sealing skirt against the ring to prevent leaking through the uncovered stent struts. Typically, the selected TMVR valve is oversized relative to the annulus, leading to the ventricular aspect of the valve “flaring” out slightly relative to the valve anchored in the mitral annulus. Implanters generally aim to flare the ventricular aspect of the transcatheter prosthesis to fully ensure that the prosthesis is well anchored against the sewing ring of the surgical valve and thereby minimizing the risk of atrial migration of the transcatheter valve over time. This should be taken into account when simulating a virtual valve implantation. Once the location of the simulated prosthetic valve is determined, the contours of the neo‐LVOT can be demonstrated by creating a standard 3‐chamber multiplanar reformat. The predicted minimal neo‐LVOT cross‐sectional area can be performed via planimetric assessment on a multiplanar reformat orthogonal to the centerline of the neo‐LVOT on the 3‐chamber multiplanar reformat. The same technique can be employed when assessing native valves, valve‐in‐valve, or valve‐in‐ring cases (Figures 6 and 7).

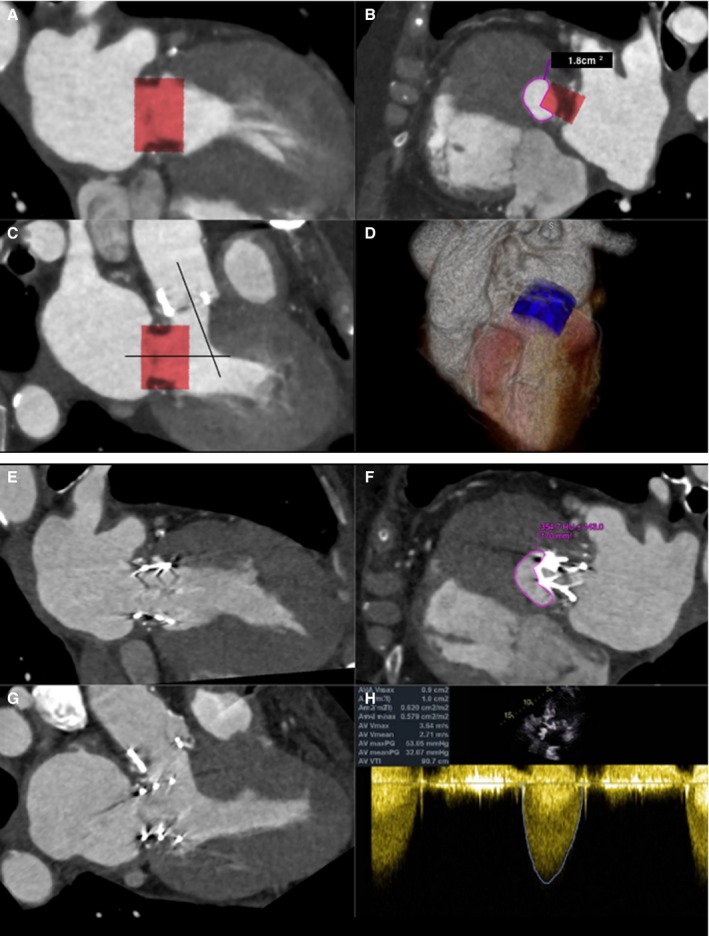

Figure 6.

A through D, ECG gated, contrast‐enhanced cardiac computerized tomography (CT) images at end systole showing (A) commissural and (B) 3‐chamber views with a simulated cylindrical device (29 mm) oriented perpendicularly to the annular plane. One third of the cylinder volume is projected to remain above the plane in the commissural view. The neo–left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) formed by the septal myocardium and the device is shown in (C) with cross‐sectional area of 2.0 cm2, indicating risk for LVOT obstruction. D, Three‐dimensional segmented rendering of the cylinder within the left ventricle. E through H, Contrast‐enhanced cardiac CT at end systole showing a deployed 26‐mm Edwards SAPIEN 3 transcatheter heart valve in the mitral position, which was placed more apically than on the 3‐dimensional (3D) simulation. Commissural (E), 3‐chamber (F), and neo‐LVOT (G) views demonstrate end‐systolic area of 0.99 cm2. A transthoracic echocardiogram (H) showed flow acceleration across the LVOT with evidence of dynamic obstruction (peak gradient measured at 58 mm Hg and mean gradient at 26 mm Hg). Despite this, the procedure was clinically successful, as the patient experienced significant improvement in her functional status. Mean gradients across the mitral valve decreased from 11 mm Hg (at a heart rate of 70 beats/min) to 6 mm Hg (at a heart rate of 80 beats/min).

Figure 7.

A through D, ECG gated, contrast‐enhanced cardiac computerized tomographic image (CT) at end systole showing (A) commissural and (B) 3‐chamber views with a simulated Edwards SAPIEN XT valve (26 mm) oriented perpendicularly to the annular plane of a bioprosthetic St. Jude valve (27 mm). Note the acute aortomitral angle. One third of the cylinder volume is projected to remain above the annular plane. The neo–left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) formed by the septal myocardium and the device is shown (C) with cross‐sectional area of 1.8 cm2, indicating high risk for LVOT obstruction. D, Three‐dimensional (3D) rendering of the cylinder within the left ventricle. E through H, Contrast‐enhanced cardiac CT at end systole showing an Edwards SAPIEN XT transcatheter heart valve (26 mm) in the mitral position. Commissural (E), 3‐chamber (F), and neo‐LVOT (G) views demonstrate end‐systolic area of 1.7 cm2. A transthoracic echocardiogram (H) showed combined peak and mean gradients across the LVOT/bioprosthetic aortic valve of 53 and 32 mm Hg. Pre–transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR) peak and mean gradients across the aortic valve were 37 and 13 mm Hg, respectively. The procedure, performed for early bioprosthetic valve failure and severe mitral regurgitation (MR), was clinically successful. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiogram showed trivial MR after the deployment of the TMVR, which translated into improved symptoms.

Limitations

Although cardiac CT provides the ability to measure the neo‐LVOT by direct planimetry, a few technical limitations deserve mention. The neo‐LVOT dimensions are dynamic rather than static measurements throughout the cardiac cycle. It is therefore conceivable that the use of multiple measurements during the cardiac phase may improve the predictive value; however, this process is labor intensive, and reference values are not yet defined. The neo‐LVOT area measurements must also be interpreted with the consideration that they are dependent on volume and loading conditions, which is especially important when dealing with a severe regurgitant lesion. The prediction of the final implant position and angle of the TMVR valve assumes that the valve will deploy directly center in the mitral annulus, which does not account for mitral annular and leaflet compliance and the angle of implant affecting the final position of the valve. Finally, there is recognition that the displacement of the native anterior mitral valve leaflet may also play a significant role in LVOT obstruction, which is not readily assessed on CT.44 Nevertheless, the CT simulation of final valve positioning provides an important starting point to guide patient and valve selection as well as implantation technique.

Use of CT to Evaluate LVOT Obstruction Following TMVR

In selected cases, when there is a high clinical concern for LVOT obstruction following TMVR due to either pre‐TMVR CT findings or post‐TMVR clinical and echocardiographic findings, cardiac CT can be used to assess the patient's anatomy, actual valve deployment, and subsequent neo‐LVOT (Figures 6 and 7). The type and characteristics of the prosthetic valve itself become relevant in determining obstruction, as some valves may allow flow through their alloy frame, which is included in the manufacturer's description of prosthesis height.

Future Opportunities

The field of TMVR is still in its infancy in terms of device design, performance, and long‐term outcomes. As is well known for transcatheter aortic valve replacement procedures, pre‐TMVR cardiac CT assessment plays a critical role in terms of patient selection, device selection and sizing, and in predicting potential complications. Novel CT‐based applications, such as the 3mensio Mitral Valve (Pie Medical Imaging, Maastricht, The Netherlands) and cvi42 (Circle Cardiovascular Imaging, Calgary, Canada) allow enhanced simulation of various valve sizes in the heart. These advanced software solutions, although not yet widely available, may further improve the capabilities of cardiac CT in pre‐TMVR planning and neo‐LVOT risk assessment. For instance, improved software may improve consistency between readers in valve sizing and save time relative to standard CT postprocessing techniques. Some institutions have advocated using computer‐aided design solutions to simulate valve sizing and position as well as to assess the risk of potential LVOT obstruction.45 3D printing techniques may also offer the potential for individual assessment of the device‐patient interaction, which may prove valuable in assessing potential complications, such as paravalvular regurgitation or neo‐LVOT obstruction.46, 47 The assessment of neo‐LVOT obstruction itself is more complicated than performing a minimal cross‐sectional area with a simulated prosthesis because of variations in loading conditions. Thus, fluid dynamic modeling may prove a useful adjunct to neo‐LVOT planimetry in the future, especially in borderline cases.

Conclusion

Cardiac CT plays an important role in the preprocedural evaluation of TMVR. The risk of neo‐LVOT obstruction, a potentially serious complication of prosthetic mitral valve placement, can be assessed on cardiac CT with the use of 3D segmentation techniques available on postprocessing software.

Disclosures

Dr Bhatt discloses the following relationships: advisory boards of Cardax, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, Medscape Cardiology, Regado Biosciences; Board of Directors of Boston VA Research Institute, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care; Chair of American Heart Association Quality Oversight Committee; data‐monitoring committees of Cleveland Clinic, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Harvard Clinical Research Institute, Mayo Clinic, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Population Health Research Institute; honoraria from American College of Cardiology (Senior Associate Editor, Clinical Trials and News, ACC.org), Belvoir Publications (Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter), Duke Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committees), Harvard Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committee), HMP Communications (Editor in Chief, Journal of Invasive Cardiology), Journal of the American College of Cardiology (Guest Editor; Associate Editor), Population Health Research Institute (clinical trial steering committee), Slack Publications (Chief Medical Editor, Cardiology Today's Intervention), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care (Secretary/Treasurer), WebMD (CME steering committees); others including Clinical Cardiology (Deputy Editor), NCDR‐ACTION Registry Steering Committee (Chair), VA CART Research and Publications Committee (Chair); research funding from Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chiesi, Eisai, Ethicon, Forest Laboratories, Ironwood, Ischemix, Lilly, Medtronic, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi Aventis, The Medicines Company; royalties from Elsevier (Editor, Cardiovascular Intervention: A Companion to Braunwald's Heart Disease); Site Co‐Investigator for Biotronik, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical (now Abbott); trustee of American College of Cardiology; unfunded research for FlowCo, Merck, PLx Pharma, Takeda. Dr Kaneko is a speaker and proctor for Edwards Lifescience. Dr Shah is a speaker and proctor for Edwards LifeSciences, educational course director for Abbott (formerly St. Jude Medical).

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e007353 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007353.)29102981

References

- 1. Nishimura RA, Vahanian A, Eleid MF, Mack MJ. Mitral valve disease—current management and future challenges. Lancet. 2016;387:1324–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feldman T, Kar S, Elmariah S, Smart SC, Trento A, Siegel RJ, Apruzzese P, Fail P, Rinaldi MJ, Smalling RW, Hermiller JB, Heimansohn D, Gray WA, Grayburn PA, Mack MJ, Lim DS, Ailawadi G, Herrmann HC, Acker MA, Silvestry FE, Foster E, Wang A, Glower DD, Mauri L; EVEREST II Investigators . Randomized comparison of percutaneous repair and surgery for mitral regurgitation: 5‐year results of EVEREST II. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2844–2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ruel M, Kulik A, Rubens FD, Bédard P, Masters RG, Pipe AL, Mesana TG. Late incidence and determinants of reoperation in patients with prosthetic heart valves. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25:364–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paradis JM, Del Trigo M, Puri R, Rodés‐Cabau J. Transcatheter valve‐in‐valve and valve‐in‐ring for treating aortic and mitral surgical prosthetic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2019–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Muller DWM, Farivar RS, Jansz P, Bae R, Walters D, Clarke A, Grayburn PA, Stoler RC, Dahle G, Rein KA, Shaw M, Scalia GM, Guerrero M, Pearson P, Kapadia S, Gillinov M, Pichard A, Corso P, Popma J, Chuang M, Blanke P, Leipsic J, Sorajja P; Tendyne Global Feasibility Trial Investigators . Transcatheter mitral valve replacement for patients with symptomatic mitral regurgitation: a global feasibility trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:381–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seiffert M, Conradi L, Baldus S, Schirmer J, Knap M, Blankenberg S, Reichenspurner H, Treede H. Transcatheter mitral valve‐in‐valve implantation in patients with degenerated bioprostheses. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Walmsley R. Anatomy of left ventricular outflow tract. Br Heart J. 1979;41:263–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mori S, Fukuzawa K, Takaya T, Takamine S, Ito T, Fujiwara S, Nishii T, Kono AK, Yoshida A, Hirata K‐I. Clinical cardiac structural anatomy reconstructed within the cardiac contour using multidetector‐row computed tomography: left ventricular outflow tract. Clin Anat. 2016;29:353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Halpern EJ, Gupta S, Halpern DJ, Wiener DH, Owen AN. Characterization and normal measurements of the left ventricular outflow tract by ECG‐gated cardiac CT: implications for disorders of the outflow tract and aortic valve. Acad Radiol. 2012;19:1252–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elliott PM, Gimeno JR, Tomé MT, Shah J, Ward D, Thaman R, Mogensen J, McKenna WJ. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and sudden death risk in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1933–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maron BJ, Maron MS, Wigle ED, Braunwald E. The 50‐year history, controversy, and clinical implications of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: from idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maron MS, Olivotto I, Betocchi S, Casey SA, Lesser JR, Losi MA, Cecchi F, Maron BJ. Effect of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction on clinical outcome in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sternik L, Zehr KJ. Systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve after mitral valve repair: a method of prevention. Tex Heart Inst J. 2005;32:47–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ducas RA, Jassal DS, Zieroth SR, Kirkpatrick ID, Freed DH. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction by a bioprosthetic mitral valve: diagnosis by cardiac computed tomography. J Thorac Imaging. 2009;24:132–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tewari P, Basu R. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction after mitral valve replacement. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:65–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu Q, Zhang L, Zhu R. Obstruction of left ventricular outflow tract after mechanical mitral valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:1789–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jett GK, Jett MD, Bosco P, van Rijk‐Swikker GL, Clark RE. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction following mitral valve replacement: effect of strut height and orientation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1986;42:299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jett GK, Jett MD, Barnhart GR, van Rijk‐Swikker GL, Jones M, Clark RE. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction with mitral valve replacement in small ventricular cavities. Ann Thorac Surg. 1986;41:70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Regueiro A, Granada JF, Dagenais F, Rodés‐Cabau J. Transcatheter mitral valve replacement: insights from early clinical experience and future challenges. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:2175–2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guerrero M, Dvir D, Himbert D, Urena M, Eleid M, Wang DD, Greenbaum A, Mahadevan VS, Holzhey D, O'Hair D, Dumonteil N, Rodés‐Cabau J, Piazza N, Palma JH, Delago A, Ferrari E, Witkowski A, Wendler O, Kornowski R, Martinez‐Clark P, Ciaburri D, Shemin R, Alnasser S, McAllister D, Bena M, Kerendi F, Pavlides G, Sobrinho JJ, Attizzani GF, George I, Nickenig G, Fassa A‐A, Cribier A, Bapat V, Feldman T, Rihal C, Vahanian A, Webb J, O'Neill W. Transcatheter mitral valve replacement in native mitral valve disease with severe mitral annular calcification: results from the first multicenter global registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:1361–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dvir D, Webb J. Mitral valve‐in‐valve and valve‐in‐ring: technical aspects and procedural outcomes. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:Y93–Y96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Spirito P, Maron BJ. Significance of left ventricular outflow tract cross‐sectional area in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a two‐dimensional echocardiographic assessment. Circulation. 1983;67:1100–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bapat V, Pirone F, Kapetanakis S, Rajani R, Niederer S. Factors influencing left ventricular outflow tract obstruction following a mitral valve‐in‐valve or valve‐in‐ring procedure, part 1. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;86:747–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Blanke P, Naoum C, Dvir D, Bapat V, Ong K, Muller D, Cheung A, Ye J, Min JK, Piazza N, Thériault‐Lauzier P, Webb J, Leipsic J. Predicting LVOT obstruction in transcatheter mitral valve implantation: concept of the neo‐LVOT. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;4:482–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blanke P, Naoum C, Webb J, Dvir D, Hahn RT, Grayburn P, Moss RR, Reisman M, Piazza N, Leipsic J. Multimodality imaging in the context of transcatheter mitral valve replacement: establishing consensus among modalities and disciplines. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1191–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Levack MM, Jassar AS, Shang EK, Vergnat M, Woo YJ, Acker MA, Jackson BM, Gorman JH, Gorman RC. Three‐dimensional echocardiographic analysis of mitral annular dynamics: implication for annuloplasty selection. Radiographics. 2012;126:S183–S188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Levine RA, Handschumacher MD, Sanfilippo AJ, Hagege AA, Harrigan P, Marshall JE, Weyman AE. Three‐dimensional echocardiographic reconstruction of the mitral valve, with implications for the diagnosis of mitral valve prolapse. Circulation. 1989;80:589–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blanke P, Dvir D, Cheung A, Levine RA, Thompson C, Webb JG, Leipsic J. Mitral annular evaluation with CT in the context of transcatheter mitral valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:612–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Movahed M‐R, Saito Y, Ahmadi‐Kashani M, Ebrahimi R. Mitral annulus calcification is associated with valvular and cardiac structural abnormalities. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2007;5:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Elgendy IY, Conti CR. Caseous calcification of the mitral annulus: a review. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36:E27–E31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Blankstein R, Durst R, Picard MH, Cury RC. Progression of mitral annulus calcification to caseous necrosis of the mitral valve: complementary role of multi‐modality imaging. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee JZ, Tey KR, Mizyed A, Hennemeyer CT, Janardhanan R, Lotun K. Mitral valve replacement complicated by iatrogenic left ventricular outflow obstruction and paravalvular leak: case report and review of literature. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schulz‐Menger J, Abdel‐Aty H, Busjahn A, Wassmuth R, Pilz B, Dietz R, Friedrich MG. Left ventricular outflow tract planimetry by cardiovascular magnetic resonance differentiates obstructive from non‐obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2006;8:741–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qin JX, Shiota T, Lever HM, Rubin DN, Bauer F, Kim Y‐J, Sitges M, Greenberg NL, Drinko JK, Martin M, Agler DA, Thomas JD. Impact of left ventricular outflow tract area on systolic outflow velocity in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a real‐time three‐dimensional echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fukuda S, Lever HM, Stewart WJ, Tran H, Song J‐M, Shin M‐S, Greenberg NL, Wada N, Matsumura Y, Toyono M, Smedira NG, Thomas JD, Shiota T. Diagnostic value of left ventricular outflow area in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a real‐time three‐dimensional echocardiographic study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:789–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vogel Claussen J, Santaularia Tomas M, Newatia A, Boyce D, Pinheiro A, Abraham R, Abraham T, Bluemke DA. Cardiac MRI evaluation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: left ventricular outflow tract/aortic valve diameter ratio predicts severity of LVOT obstruction. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;36:598–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guerrero M, Wang DD, Himbert D, Urena M, Pursnani A, Kaddissi G, Iyer V, Salinger M, Chakravarty T, Greenbaum A, Makkar R, Vahanian A, Feldman T, O'Neill W. Short‐term results of alcohol septal ablation as a bail‐out strategy to treat severe left ventricular outflow tract obstruction after transcatheter mitral valve replacement in patients with severe mitral annular calcification. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2017; Epub ahead of print Mar 7. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mylotte D, Piazza N. Transcatheter mitral valve implantation: a brief review. EuroIntervention. 2015;11(suppl W):W67–W70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. De Backer O, Piazza N, Banai S, Lutter G, Maisano F, Herrmann HC, Franzen OW, Søndergaard L. Percutaneous transcatheter mitral valve replacement: an overview of devices in preclinical and early clinical evaluation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:400–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Conradi L, Silaschi M, Seiffert M, Lubos E, Blankenberg S, Reichenspurner H, Schaefer U, Treede H. Transcatheter valve‐in‐valve therapy using 6 different devices in 4 anatomic positions: clinical outcomes and technical considerations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1557–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grasso C, Capodanno D, Tamburino C, Ohno Y. Current status and clinical development of transcatheter approaches for severe mitral regurgitation. BMC Med Imaging. 2015;79:1164–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Preston‐Maher GL, Torii R, Burriesci G. A technical review of minimally invasive mitral valve replacements. Cardiovasc Eng Technol. 2015;2:174–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Food and Drug Administration Press Announcements—FDA expands use of Sapien 3 artificial heart valve for high‐risk patients. 2017. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm561924.htm. Accessed October 28 2017.

- 44. Babaliaros VC, Greenbaum AB, Khan JM, Rogers T, Wang DD, Eng MH, O'Neill WW, Paone G, Thourani VH, Lerakis S, Kim DW, Chen MY, Lederman RJ. Intentional percutaneous laceration of the anterior mitral leaflet to prevent outflow obstruction during transcatheter mitral valve replacement: first‐in‐human experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:798–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang DD, Eng M, Greenbaum A, Myers E, Forbes M, Pantelic M, Song T, Nelson C, Divine G, Taylor A, Wyman J, Guerrero M, Lederman RJ, Paone G, O'Neill W. Predicting LVOT obstruction after TMVR. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:1349–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vaquerizo B, Thériault‐Lauzier P, Piazza N. Percutaneous transcatheter mitral valve replacement: patient‐specific three‐dimensional computer‐based heart model and prototyping. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2015;68:1165–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ripley B, Kelil T, Cheezum MK, Goncalves A, Di Carli MF, Rybicki FJ, Steigner M, Mitsouras D, Blankstein R. 3D printing based on cardiac CT assists anatomic visualization prior to transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016;10:28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]