Abstract

Molecular oscillators are important cellular regulators of, for example, circadian clocks, oscillations of immune regulators, and short-period (ultradian) rhythms during embryonic development. The Notch signaling factor HES1 (hairy and enhancer of split 1) is a well-known repressor of proneural genes, and HES1 ultradian oscillation is essential for keeping cells in an efficiently proliferating progenitor state. HES1 oscillation is driven by both transcriptional self-repression and ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. However, the E3 ubiquitin ligase targeting HES1 for proteolysis remains unclear. Based on siRNA-mediated gene silencing screening, co-immunoprecipitation, and ubiquitination assays, we discovered that the E3 ubiquitin ligase SCFFBXL14 complex regulates HES1 ubiquitination and proteolysis. siRNA-mediated knockdown of the Cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligases RBX1 or CUL1 increased HES1 protein levels, prolonged its half-life, and dampened its oscillation. FBXL14, an F-box protein for SCF ubiquitin ligase, associates with HES1. FBXL14 silencing stabilized HES1, whereas FBXL14 overexpression decreased HES1 protein levels. Of note, the SCFFBXL14 complex promoted the ubiquitination of HES1 in vivo, and a conserved WRPW motif in HES1 was essential for HES1 binding to FBXL14 and for ubiquitin-dependent HES1 degradation. HES1 knockdown promoted neuronal differentiation, but FBXL14 silencing inhibited neuronal differentiation induced by HES1 ablation in mES and F9 cells. Our results suggest that SCFFBXL14 promotes neuronal differentiation by targeting HES1 for ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis and that the C-terminal WRPW motif in HES1 is required for this process.

Keywords: E3 ubiquitin ligase, neurodifferentiation, proteolysis, small interfering RNA (siRNA), ubiquitylation (ubiquitination), FBXL14, HES1 oscillation, SCF ubiquitin ligase

Introduction

Molecular oscillators (biological clocks) are widespread and important in living cells, such as circadian clocks (1, 2), the cell cycle (1, 3), oscillations of immune system regulators (4), and short period (ultradian) rhythms during somitogenesis (5–7). Notch signaling factors HES1 (hairy and enhancer of split 1) and HES7 are periodically expressed in the presomitic mesoderm. Each cycle is associated with somite formation, which is called the segmentation clock (7–10). Disruption of the segmentation clock can result in severely disordered somites (8). Serum stimulation–induced oscillatory expression of HES1 was experimentally revealed in cultured cells, including mouse teratocarcinoma cells (F9), mouse embryonic stem cells (ES), and neuronal stem cells (6, 10–12). It is becoming clear that the same oscillation mechanism works in cultured cells and presomitic mesoderm (6, 10, 13). Furthermore, HES1 is a master transcriptional repressor of proneural genes and precludes neuronal differentiation (14, 15). The indispensable role of HES1 in regulating neuronal differentiation is evidenced by precocious neuronal differentiation and the hypoplasia of brain in HES1-null mice (16, 17). HES1 low expression ES cells expressed a higher level of neural marker genes including Tuj1 and Mash1, suggesting that HES1-low cells more efficiently differentiated into neurons (11, 18). Indeed, these pioneering works suggest that the oscillatory versus sustained HES1 expression are important for keeping cells in an efficiently proliferating progenitor state, whereas constitutive down-regulation of HES1 leads to neuronal differentiation (19–21). Therefore, it is now crucial to understand the molecular mechanism of HES1 oscillation.

It is well documented that HES1 oscillation is driven by transcriptional self-repression and ubiquitin-dependent HES1 proteolysis (6). After activation of HES1 transcription via Notch signaling or serum stimulation, HES1 binds to its own promoter at the putative N-box and represses its own expression (6). HES1 is highly unstable and degraded with a half-life of ∼20 min, which results in the release of HES1 from its promoter and allows the next round of HES1 expression (6). HES1 oscillation was regulated by Notch (12), Jak2-Stat3 (20), BMP, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF)5 (11) pathways, and miRNA-9 (21, 22) at transcriptional level. It is evidenced that Usp27x, Usp22, and Usp51 deubiquitinate HES1 (23), but the specific E3 ligase for HES1 ubiquitination has not been identified.

Cullin-RING (either RBX1 or RBX2) E3 ligases (CRLs) are the largest family of E3 ubiquitin ligases (24), which include eight Cullin proteins (CUL1, 2, 3, 4A, 4B, 5, 7, and 9) that form similar CRL complexes. The complex of CUL1 with the RING protein RBX1, SKP1, and F-box protein (CRL1/SCF E3 ligases) mediates the timely proteolysis of many important proteins and acts as a major regulator of various cellular processes including circadian clock (25–28), cell cycle (29–32), apoptosis (33, 34), and metabolism (35). F-box proteins were the substrate-specific receptors for SCF E3 ligases (24, 36–38). So far, more than 70 human F-box proteins have been identified in human genome, only a few of them have been characterized (24, 37, 38). FBXL14, which contains 11 leucine-rich repeats and an F-box motif (37), can ubiquitinate SNAI1 and c-Myc in mammalian cells (39, 40). Its Xenopus homologue, Ppa, regulates expression of epithelial mesenchymal transition factors including Twist, Snai1, Slug, and Sip1 in the neural crest development of Xenopus laevis (41). FBXL14 is also essential for vertebrate axis formation in zebrafish (42). Deletion of FBXL14 has been reported to associate with the neurological disorders (43). However, the molecular mechanism of FBXL14 in regulating neuronal differentiation has not been elucidated.

In this study, we found that the SCFFBXL14 E3 ubiquitin ligase targets HES1 for ubiquitination and degradation, elucidating a critical mechanism for the regulation of HES1 oscillation and neuronal differentiation. The comprehensive understanding of HES1 ubiquitin-dependent degradation offers new insights into mouse somitogenesis, neuronal differentiation, and some human neurological disorders.

Results

RBX1 regulates HES1 stability and oscillation

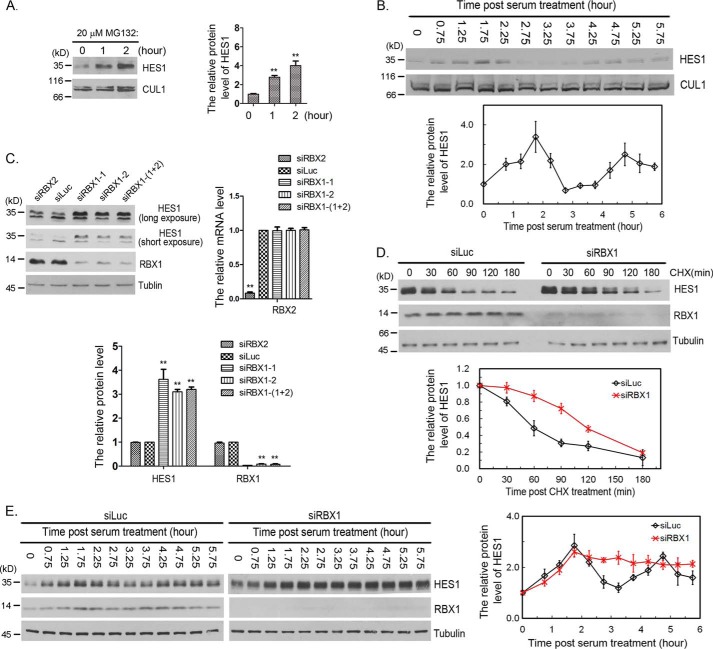

We found that proteasome inhibitor MG132 treatment led to significant increase of HES1 protein level in F9 cells (Fig. 1A). To examine HES1 protein oscillation, we serum-starved F9 cells for 24 h and analyzed temporal changes of HES1 protein level after serum stimulation. The protein level of HES1 oscillated with a period of 3 h, reaching its first peak at ∼1.75 h, in F9 cells (Fig. 1B). These results were consistent with those observed by Hirata et al. (6).

Figure 1.

RBX1 regulated HES1 stability and oscillation. A, MG132 stabilized HES1 in F9 cells. F9 cells were treated with 20 μm MG132 for the indicated times, and the cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibody for HES1. CUL1 was taken as loading control. Right panel, the relative protein levels of HES1 in blots were quantified by Gel-Pro analyzer 4, which was normalized to CUL1. The means and error bars were generated from three independent experiments. Error bars indicated S.D. The statistical differences between control group (0 h) and experimental groups (1 and 2 h) were measured by paired two-sided Student's t test (**, p < 0.01). B, serum-induced HES1 oscillation. F9 cells were serum-starved for 24 h, and HES1 protein levels were examined at the indicated times once serum was supplemented. Bottom panel, the relative protein level of HES1 was measured as in A. The means and error bars (S.D.) were from three independent experiments. C, silencing of RBX1 resulted in stabilization of HES1. F9 cells were transfected with 50 nm luciferase, RBX2, or RBX1 siRNAs for 48 h, and cells were harvested for immunoblotting using specific antibodies. Bottom panel, the relative protein levels of HES1 and RBX1 were quantified and normalized to tubulin. The mRNA level of RBX2 was examined using quantitative real-time PCR (right panel). The means and error bars (S.D.) were generated from three independent experiments. The significance of statistical difference between control group (Luc) and experimental groups (RBX1 and RBX2) were calculated as in A. D, knocking down of RBX1 postponed the degradation of HES1. F9 were transfected with siRNA targeting to Luc or RBX1 for 45 h. Then cells were treated with CHX (100 μg/ml) for the indicated times, and the protein levels of HES1, RBX1, and tubulin were determined by Western blotting. Bottom panel, the relative protein level of HES1 was quantified and normalized to tubulin. The experiment was biologically repeated at least five times. E, silencing of RBX1 dampened HES1 oscillation. F9 cells were transfected with luciferase or RBX1 siRNAs for 24 h and then cultured for another 18.5 h with serum retraction to starve cells. The protein level of HES1 was examined at the indicated times once serum was supplemented to the medium. Right panel, the quantification of relative protein level of HES1. The experiment was biologically repeated at least five times.

To investigate the potential involvement of CRLs in HES1 proteasome degradation, we initially focused on the potential effects of RBX inactivation on HES1 protein level. We designed siRNAs specifically targeting RBX1 or RBX2, and the efficacy of siRNAs was ∼85–95% reduction (Fig. 1C). Knockdown of RBX1 by either of the two siRNAs significantly increased the protein level of HES1, whereas abolishment of RBX2 had a negligible effect on HES1 protein level (Fig. 1C), suggesting that RBX1 controls the degradation of HES1. We further performed HES1 decay essay with cycloheximide (CHX, protein synthesis inhibitor) and found that knockdown of RBX1 increased the half-life of HES1 from ∼50 to ∼110 min (Fig. 1D). These data indicate that RBX1 regulates HES1 degradation and stability.

To study the biological importance of RBX1-mediated degradation of HES1, we investigated whether RBX1 modulates HES1 oscillation. After RBX1 or luciferase (Luc) were depleted by siRNAs for 24 h, the cells were synchronized by serum removal for 18.5 h and readdition of serum. The changes of HES1 protein levels were analyzed at various times after serum restimulation. Our studies revealed that the overall level of HES1 protein in RBX1 knockdown cells was higher than that in control (Luc-siRNA treatment) cells, and RBX1 knockdown damped HES1 oscillation (Fig. 1E). In the control group, the protein level of HES1 reached the first peak at ∼1.75 h and the second peak at ∼4.75 h; the trough occurred at ∼3.25 h (Fig. 1E). Whereas in the RBX1 depleted cells, the protein level of HES1 reached its peak at ∼1.75 h and then kept high level without a trough or second peak (Fig. 1E). These results suggest that RBX1 regulates HES1 oscillation. Taken together, our studies revealed that RBX1 regulates HES1 oscillation by targeting HES1 for degradation.

CUL1 interacts with HES1 and regulates HES1 degradation

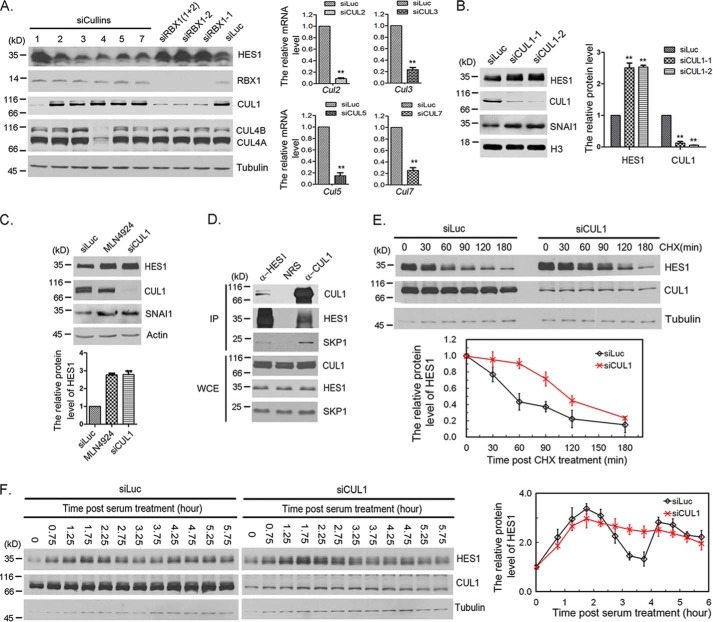

To identify the Cullin that mediates HES1 ubiquitination, we screened Cullins by knocking down each Cullin in F9 cells. We found that knockdown of CUL1, but not other Cullins, induced an increase in the HES1 protein level (Fig. 2A). We confirmed this finding by another siRNA specifically targeted CUL1 (Fig. 2B). To further test the possibility that another CRL E3 ligase might be involved in the regulation of HES1, we compared the HES1 protein stability in cells treated with CRL inhibitor MLN4924 and CUL1 siRNA. Western blotting showed that MLN4924 treatment and CUL1 knockdown increased comparable fold change on HES1 protein level (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that CRL1/SCF is the major ligase that mediates HES1 degradation in CRL E3 ligases. Furthermore, the interaction of HES1, CUL1, and SKP1 was observed in F9 cells after treatment with MG132 for 3 h, which prevented the degradation of HES1 (Fig. 2D). Knockdown of CUL1 increased the half-life of HES1 from ∼50 to ∼110 min (Fig. 2E). These results indicate that the RBX1–CUL1–SKP1 complex interacts with HES1 and regulates HES1 degradation.

Figure 2.

CUL1 regulated HES1 stability and oscillation. A, Cullin family screening by siRNA. F9 cells were transfected with 50 nm Luc, RBX1, or Cullins siRNAs as indicated for 48 h, and the cells were harvested for Western blotting. Right panel, the mRNA level of CUL2, CUL3, CUL5, and CUL7 was examined using quantitative real-time PCR. The error bars represent S.D. from three independent experiments. The statistical difference was measured by paired two-sided Student's t test (**, p < 0.01). B, CUL1 regulated HES1 stability. F9 cells were transfected with 50 nm Luc or CUL1 (CUL1-1 and CUL1-2) siRNAs for 48 h, and the cells were harvested for Western blotting. The quantification of protein levels of HES1 and CUL1 were measured as in Fig. 1A. The error bars represent S.D. from three independent experiments. C, SCF is the major E3 ligase involved in HES1 degradation among CRL E3 ligases. F9 cells were transfected with 50 nm Luc and CUL1 siRNAs for 48 h or treated with 0.5 μm MLN4924 for 12 h, and cells were harvested for Western blotting. The quantification of protein levels of HES1 was measured as in Fig. 1A. The error bars represent S.D. from three independent experiments. The statistical difference was measured as in Fig. 1A. D, SCF complex interacted with HES1. F9 cells were treated with 20 μm MG132 for 3 h, the cells were harvested and analyzed by co-immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blotting using antibodies against HES1, CUL1, and SKP1. Rabbit IgG (normal rabbit serum, NRS) was taken as negative control. Immunoblots of whole-cell extracts (WCE) are shown at the bottom. E, silencing of CUL1 resulted in stabilization of HES1. F9 cells were transfected with luciferase or CUL1 siRNAs for 45 h, and the cells were treated with CHX (100 μg/ml) for the indicated times. The protein levels of HES1, CUL1, and tubulin were determined by Western blotting. Bottom panel, the relative protein level of HES1 was quantified and normalized to tubulin. F, silencing of CUL1 disrupted HES1 oscillation. F9 cells were transfected with luciferase or CUL1 siRNAs for 24 h followed by serum-withdrawal starvation for 18.5 h. The cells were harvested at the indicated times once serum was supplemented. The protein level of HES1 was examined at the indicated times once serum was supplemented to the medium. Right panel, the quantification of relative protein level of HES1. The experiment was biologically repeated at least five times.

We also analyzed the changes of HES1 oscillation after depletion of CUL1. We found that CUL1 knockdown damped HES1 oscillation (Fig. 2F). The behavior of HES1 in CUL1 knockdown cells phenocopied that in RBX1 knockdown. The overall level of HES1 protein in CUL1 knockdown cells was higher than that in the control cell (Fig. 2F). In the CUL1 depleted cells, HES1 protein level reached its peak at ∼1.75 h and then kept to a high level without trough or second peak (Fig. 2F). Altogether, the data presented in Figs. 1 and 2 suggest that the RBX1–CUL1–SKP1 complex modulates HES1 oscillation by directly interacting with HES1 and regulating HES1 degradation.

FBXL14 interacts with HES1 and promotes HES1 proteasome degradation

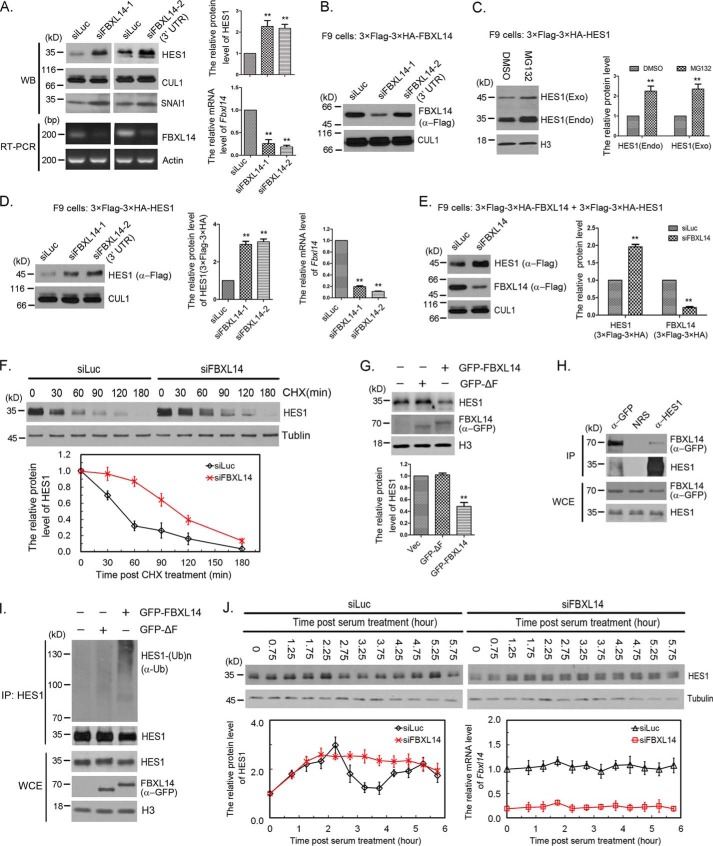

To identify the F-box proteins that mediate HES1 degradation, we screened the F-box proteins by siRNAs. F-box protein fell into three major classes: FBXWs, FBXLs, and FBXOs. FBXW means a protein with an F-box motif and WD repeats; FBXL denotes a protein containing an F-box and leucine-rich repeats (LRRs); and FBXO stands for a protein with an F-box and either another or no other motif. We screened all of the FBXW family members (FBXW1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12) and FBXL family members (FBXL1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, and 22), as well as several FBXOs known as SCF adapters (FBXO7, 8, and 24). After repeated experiments, we narrowed down the candidate to FBXL14, whose knockdown by siFBXL14-1 can significantly increase the protein level of HES1 (more than 2-fold) (Fig. 3A). We further confirm this finding by another siRNA specifically targeted FBXL14 3′-UTR (siFBXL14-2). Knockdown of FBXL14 by either of the two siRNAs significantly increased the protein level of HES1 (Fig. 3A). To quantify the efficacy of FBXL14 siRNAs, we measured the mRNA level of FBXL14 using quantitative real-time PCR and semi-quantitative RT-PCR because antibodies that recognized FBXL14 were not available. The mRNA levels of FBXL14 were reduced to 10–25% (Fig. 3A). The FBXL14 siRNAs efficacy was also tested in stably expressing 3× FLAG–3× HA–FBXL14 F9 cells. As expected, siFBXL14-1, but not siFBXL14-2 (3′-UTR), was efficient in depleting exogenous FBXL14 when compared with Luc siRNAs (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

FBXL14 was the F-box for SCF complex-mediated HES1 ubiquitination and degradation. A, FBXL14 regulated HES1 stability. The protein levels of HES1 and CUL1 were determined by Western blotting using indicated antibodies (left panel) and quantified (right panel). The quantification of protein levels of HES1 were measured as in Fig. 1A. FBXL14 mRNA inhibition was assessed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. Right panel, the mRNA level of FBXL14 was examined using quantitative real-time PCR. The error bars represent S.D. from five independent experiments. The statistical difference between control group (Luc) and experimental groups (FBXL14) was measured by paired two-sided Student's t test (**, p < 0.01). B, the efficacy of FBXL14 siRNAs. Stably expressing 3× FLAG–3× HA–FBXL14 F9 cells were transfected with 50 nm FBXL14-1 or FBXL14-2 siRNAs as indicated for 45 h, and the cells were harvested for Western blotting. The protein levels of exogenous FBXL14 and CUL1 were determined by Western blotting as indicated. C, the protein level and stability of exogenous and endogenous HES1 in stably expressing 3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 F9 cells. The protein levels of exogenous and endogenous HES1 were determined by Western blotting using anti-HES1 antibody (left panel) and quantified as in Fig. 1A, which was normalized to histone H3 (right panel). The statistical difference between control group (DMSO) and experimental groups (MG132) was measured as in A. D, FBXL14 regulated the stability of exogenous HES1. Stably expressing 3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 F9 cells were transfected with luciferase or FBXL14 (FBXL14-1 and FBXL14-2) siRNAs for 45 h. The protein levels of exogenous HES1 (3× FLAG–3× HA) and CUL1 were determined by Western blotting using indicated antibodies (left panel) and quantified (middle panel). Right panel, the mRNA level of FBXL14 was examined and quantified as in A. The error bars represent S.D. from three independent experiments. The statistical difference between control group (Luc) and experimental groups (FBXL14) was measured as in A. E, deletion of FBXL14 stabilized exogenous HES1. Stably co-expressing 3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 and 3× FLAG–3× HA–FBXL14 F9 cells were transfected with FBXL14 (FBXL14-1) or luciferase siRNAs for 45 h, and cell lysates were immunoblotted using anti-FLAG antibody. Right panel, the protein levels of exogenous HES1 (3× FLAG–3× HA) and FBXL14 (3× FLAG–3× HA) were quantified. The error bars represent S.D. from three independent experiments. The statistical difference between control group (Luc) and experimental groups (FBXL14) was measured as in A. F, silencing of FBXL14 resulted in stabilization of HES1. F9 cells were transfected with luciferase or FBXL14 siRNAs for 45 h, and the cells were treated with CHX (100 μg/ml) for the indicated times. The protein levels of HES1 and tubulin were determined by Western blotting. Bottom panel, the relative protein level of HES1 was quantified and normalized to tubulin. G, FBXL14 promoted HES1 degradation. F9 cells were transfected with pEGFP-C2 (Vec), pEGFPC2–FBXL14 ΔF, or pEGFPC2–FBXL14 for 48 h, and endogenous HES1 and exogenous FBXL14 were detected by Western blotting. Bottom panel, the protein levels of HES1 was quantified. The error bars represent S.D. from three independent experiments. The statistical difference between control group (Vec) and experimental groups (GFP-ΔF and GFP–FBXL14) was measured as in A. H, FBXL14 interacted with HES1. F9 cells were transfected with pEGFPC2–FBXL14 for 48 h, and the cells were treated with 20 μm MG132 for 3 h, harvested, and analyzed by co-immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blotting. The experiment was biologically repeated at least three times. I, SCF complex promoted HES1 polyubiquitination in vivo. GFP–FBXL14, GFP–FBXL14 ΔF, and pEGFP-C2 were expressed in F9 cells for 44 h, and MG132 was added 3 h before cell harvesting to stabilize ubiquitylated protein. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with HES1 antibody under denaturing conditions (radioimmune precipitation assay buffer), and immunocomplexes were analyzed with the indicated antibodies. Immunoblots of whole-cell extracts were shown at the bottom. J, silencing of FBXL14 disrupted HES1 oscillation. F9 cells were transfected with luciferase or FBXL14 siRNAs for 24 h followed by serum-withdrawal starvation for 18.5 h. The cells were harvested at the indicated times once serum was supplemented. The protein level of HES1 was examined at the indicated times once serum was supplemented to the medium. Bottom panel, the quantification of relative protein level of HES1 and the relative mRNA level of Fbxl14. The experiment was biologically repeated at least five times.

HES1 is regulated by self-repression at the transcription level and ubiquitin-dependent degradation at the protein level. To distinguish the effects resulted from protein degradation or transcriptional regulation, we generated stable F9 cells that expressed exogenous HES1 (3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1) at low level (near or less then physiologic levels). The exogenous HES1 was controlled by exogenous LTR promoter of the recombinant murine stem cell virus (MSCV) retroviral expression system. The expression of exogenous HES1 was lower than that of endogenous HES1, and both exogenous HES1 and endogenous HES1 were very sensitive to MG132 (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, FBXL14 knockdown significantly increased the protein level of exogenous HES1 (Fig. 3, D and E). Similar results were observed in both stably expressing 3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 and 3× FLAG–3× HA–FBXL14 F9 cells. Silencing of FBXL14 notably increased the protein level of 3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1, whereas the protein level of 3× FLAG–3× HA-FBXL14 was dramatically reduced, which was detected by anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 3E). These results suggest that the same proteolysis mechanism works on exogenous and endogenous HES1 in this stable F9 cells.

Next, we performed HES1 decay essay and found that knockdown of FBXL14 increased the half-life of HES1 from ∼50 to ∼90 min (Fig. 3F). This further confirms that FBXL14 regulates HES1 degradation and stability.

To further examine the efficiency of FBXL14 promotes HES1 degradation in vivo, we overexpressed GFP–FBXL14 in F9 cells and GFP–FBXL14 ΔF (a mutant deleted F-box domain that is required for the interaction with the SCF complex), or pEGFP-C2 vector was transfected as control. As shown in Fig. 3G, transfection of full-length GFP–FBXL14, but not GFP–FBXL14 ΔF or pEGFP-C2 vector, promoted HES1 degradation. To determine whether the effects of FBXL14 on HES1 were directly through protein-protein interactions, we immunoprecipitated either HES1 or GFP–FBXL14 in F9 cells expressing GFP–FBXL14 and found that GFP–FBXL14 associated with endogenous HES1 (Fig. 3H). These results indicate that FBXL14 interacts with HES1 and regulates HES1 degradation.

Because our data indicate that FBXL14 functions to recruit the SCF E3 ligase to HES1 and promote its degradation, we investigated whether SCFFBXL14 stimulates HES1 ubiquitination. GFP–FBXL14, GFP–FBXL14 ΔF, or pEGFP-C2 were expressed in F9 cells for 44 h, and MG132 was added 3 h before cell harvesting to stabilize ubiquitylated protein. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HES1 antibody under denaturing conditions (radioimmune precipitation assay buffer) to ensure that other ubiquitylated proteins were not associated with HES1, and immunocomplexes were analyzed with anti-ubiquitin antibody. Western blotting shows that transfection of GFP–FBXL14 increases the amount of polyubiquitylated HES1 compared with GFP–FBXL14 ΔF or pEGFP-C2 (Fig. 3I).

Because of RBX1 and CUL1 regulated HES1 oscillation, we next analyzed the changes of HES1 oscillation after depletion of FBXL14. We found that FBXL14 knockdown damped HES1 oscillation as well (Fig. 3J). The behavior of HES1 in FBXL14 knockdown cells phenocopied that in RBX1 or CUL1 knockdown cells. Altogether, the data presented in Figs. 1–3 suggest that the RBX1–CUL1–SKP1–FBXL14 complex modulates HES1 oscillation by directly interacting with HES1 and regulating HES1 proteolysis.

The conserved WRPW motif is essential for HES1 binding to FBXL14 and degradation

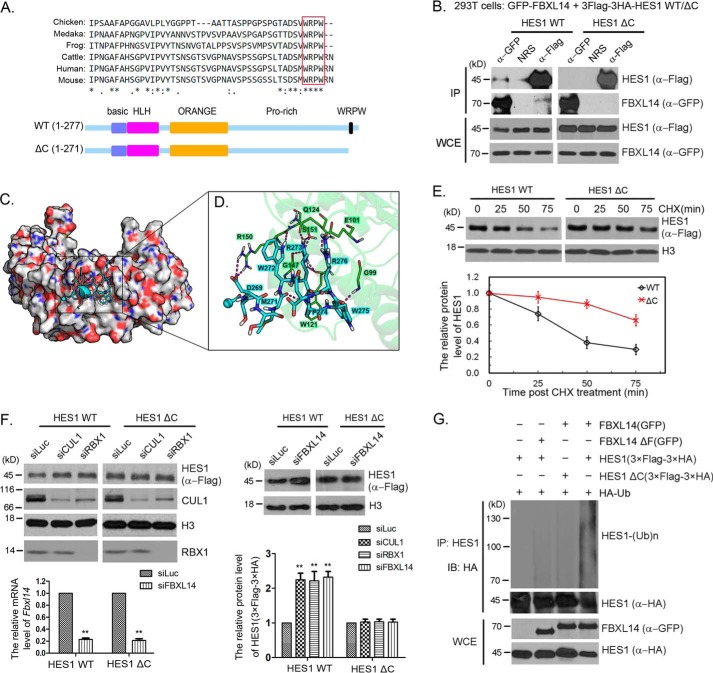

Next, we tried to map the regions in HES1 that affected FBXL14 binding to HES1. HES1 contains a highly conserved WRPW motif at its C terminus (Fig. 4A). We constructed a 3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 ΔC mutant, which deleted the C-terminal WRPW motif (Fig. 4A). 293T cells were co-transfected with pMSCV–3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 or pMSCV–3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 ΔC mutant, and pEGFPC2–FBXL14 or pEGFPC2–FBXL14 ΔF, respectively, to detect association between FBXL14 and HES1 by co-immunoprecipitation. Our studies show that deletion of the WRPW motif reduced the interaction between HES1 and FBXL14 (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

The WRPW motif was required for HES1 ubiquitination and degradation. A, highly conserved WRPW motif and schematic diagram for HES1 ΔC mutant. Six amino acids were deleted on the C-terminal of HES1. B, deletion of WRPW motif reduced the interaction between HES1 and FBXL14. 293T cells were co-transfected with pEGFPC2–FBXL14 and pMSCV–3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 or pMSCV–3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 ΔC. Co-immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed using anti-GFP and anti-FLAG antibodies. The experiment was biologically repeated at least three times. C, predicted binding mode of FBXL14 and the WRPW motif. Peptide-binding interface of the FBXL14 leucine-rich domain, from the MD simulation. The CH3 group of blocked acetyl at N terminus is shown as a sphere. Carboxyl oxygen and amino nitrogen atoms are colored red and blue, respectively. D, detailed view of the key interactions between the WRPW motif and FBXL14 leucine-rich domain. E, the WRPW motif was critical for HES1 degradation. Stably expressing 3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 WT or 3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 ΔC F9 cells were treated with CHX for the indicated times, and then the cells were harvested for Western blotting to detect the protein level changes of HES1. The error bars represent S.D. from three independent experiments. F, SCFFBXL14 complex did not degrade HES1 ΔC mutant. Stably expressing 3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 or 3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 ΔC mutant F9 cells were transfected with luciferase, RBX1, CUL1, or FBXL14 siRNAs. Cell lysates were immunoblotted (IB) for the indicated proteins. The protein levels in the blots were quantified and plotted at the bottom. The error bars represent S.D. from three independent experiments. The significance of statistical difference was calculated by paired two-sided Student's t test (**, p < 0.01). G, WRPW motif was essential for SCFFBXL14 catalyzing HES1 ubiquitination. 293T cells were co-transfected with pMSCV–3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 or pMSCV–3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 ΔC, pEGFPC2–FBXL14, or pEGFPC2–FBXL14 ΔF and pRK5-HA-Ub as indicated for 44 h followed by incubated with MG132 for 4 h, and the cells were harvested for immunoprecipitation using anti-HES1 antibody under denaturing condition and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody. Whole-cell extracts (WCE) were immunoblotted with anti-GFP and anti-HA antibodies to indicate expression of exogenous FBXL14 and HES1. The experiment was biologically repeated at least three times.

To further understand the interaction between HES1 and FBXL14 observed above, we predicted the possible binding mode between the WRPW motif of HES1 and the LRR domain of FBXL14, using theoretical calculations (Fig. 4, C and D). The structure of FBXL14-LRR domain was modeled using multiple homology templets and verified by predicted secondary structures of the full-length FBXL14. Then the structure of the WRPW motif was docked into the FBXL14-LRR using a holistic molecular docking pipeline HoDock (44, 45). The predicted complex structure maintained stable during subsequent molecular dynamics (MD) simulation for further optimization. In this model (Fig. 4C), the positively charged side chains of tryptophan (Trp272) and arginine (Arg273) in WRPW motif bind into a deep negatively charged pocket on the α-helix side of FBXL14-LRR domain. Furthermore, Pro274 and Trp275 could also provide hydrophobic interactions with the residues located around the binding pocket, such as Trp121 on the LRR domain (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these predictions provide us a possible model about how the WRPW motif and FBXL14 interact. However, whether the WRPW motif itself is sufficient to bind FBXL14 needs to be clarified in future work.

We also noticed that the protein level of HES1 ΔC is higher than that of HES1 WT, indicating that FBXL14 promoted HES1 WT degradation rather than HES1 ΔC. Therefore, we tested the possibility that the WRPW motif was critical for HES1 degradation mediated by SCFFBXL14 via measuring the half-life of wild-type and the ΔC mutant of HES1. Notably, we found that the half-life of HES1 ΔC mutant was indeed significantly increased compared with that of wild-type HES1 (Fig. 4E). We also found that the protein level of wild-type HES1 was increased after deletion of RBX1, CUL1, or FBXL14, whereas the change of HES1 ΔC mutant protein level was not observed (Fig. 4F). These studies indicate that the WRPW motif is required for HES1 degradation mediated by the SCFFBXL14 complex.

To further investigate the effect of FBXL14 on HES1 and HES1 ΔC mutant, 293T cells were co-transfected with pRK5-HA-Ub, pMSCV–3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 or pMSCV–3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 ΔC mutant, and pEGFPC2–FBXL14 or pEGFPC2–FBXL14 ΔF (F-box deletion mutant) for 44 h, and MG132 was added 4 h before cell harvesting. The lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HES1 antibody under denaturing conditions, and immunocomplexes were analyzed with anti-HA antibody. The expression of GFP–FBXL14 dramatically increased the ubiquitination of HES1 compared with the control (without GFP–FBXL14 or GFP–FBXL14 ΔF) and GFP–FBXL14 ΔF mutant (Fig. 4G). Despite co-expression of GFP–FBXL14, polyubiquitylation of HES1 ΔC was significantly less than that of HES1 WT, indicating that the WRPW motif of HES1 was required for SCFFBXL14-mediated ubiquitination (Fig. 4G). Thus, our data supported that the WRPW motif was required for efficient SCFFBXL14-mediated HES1 ubiquitination and degradation.

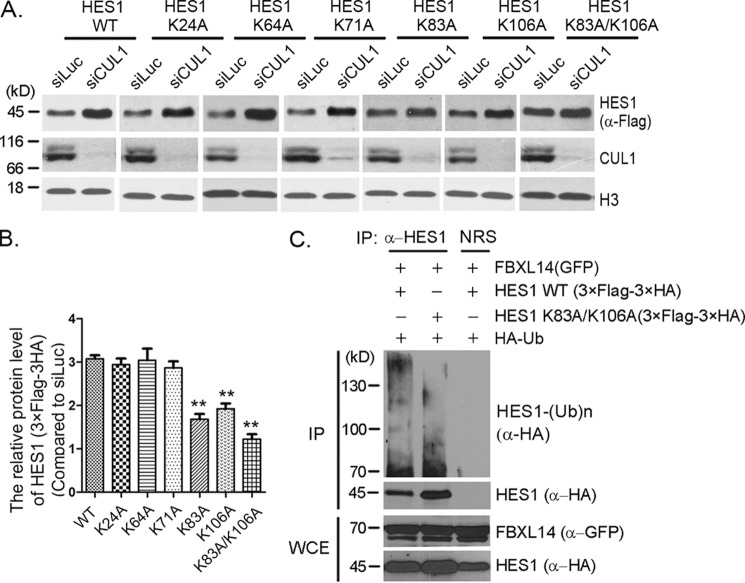

Lysine 83 and lysine 106 are potential sites for SCFFBXL14-mediated HES1 ubiquitination

We further analyzed the lysines that may be involved in SCFFBXL14-mediated HES1 ubiquitination. We mutated lysines 24, 64, 71, 83, and 106 to alanines, respectively. HES1 mutants bearing K24A, K64A, or K71A were also sensitive to CUL1 knockdown, and the changes of protein levels were similar to WT, whereas K83A and K106A mutants showed partial sensitivity to CUL1 knockdown, and the protein levels only increased ∼60% compared with WT (Fig. 5, A and B). Double mutant K83A/K106A presented more resistant to CUL1 knockdown (Fig. 5, A and B). The in vivo ubiquitination assay also showed that the ubiquitination of the K83A/K106A mutant was reduced compared with that of HES1 WT in the presence of FBXL14 (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that lysines 83 and 106 are involved in SCFFBXL14-mediated HES1 ubiquitination. Consistent with our result, Lys83 and Lys106 had been identified as ubiquitination sites by Wagner et al. (46) in a mass spectrometry–based proteome-wide ubiquitination sites analysis. However, there was still residual ubiquitination presented in the double mutant K83A/K106A, indicating that other ubiquitination sites could have a role (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Lysines 83 and 106 were potential ubiquitination sites for SCFFBXL14-mediated HES1 ubiquitination. A, lysine mutants screening. Stably expressing 3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 WT or mutants (as indicated) F9 cells were transfected with luciferase or CUL1 siRNAs for 45 h, and cell lysates were immunoblotted using indicated antibodies. Histone H3 was taken as loading control. B, quantification of the relative protein levels of HES1 and mutants in A. The quantification of protein levels was measured as in Fig. 1A. The statistical difference between the control group (WT) and experimental groups (K24A, K64A, K71A, K83A, K106A, and K83A/K106A) was measured. The error bars represent S.D. from three independent experiments. The significance of statistical difference was calculated by paired two-sided Student's t test (**, p < 0.01). C, HES1 was ubiquitinated by FBXL14 through lysines 83 and 106. 293T cells were co-transfected with pMSCV–3× FLAG–3× HA–HES1 or pMSCV–3× FLAG–3× HA-0HES1 (K83A/K106A), pEGFPC2–FBXL14, and pRK5-HA-Ub as indicated for 44 h followed by incubation with MG132 for 4 h, and the cells were harvested for immunoprecipitation (IP) using anti-HES1 antibody under denaturing condition and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody. Whole-cell extracts (WCE) were immunoblotted with anti-GFP and anti-HA antibodies to indicate expression of exogenous FBXL14 and HES1. The experiment was biologically repeated at least three times.

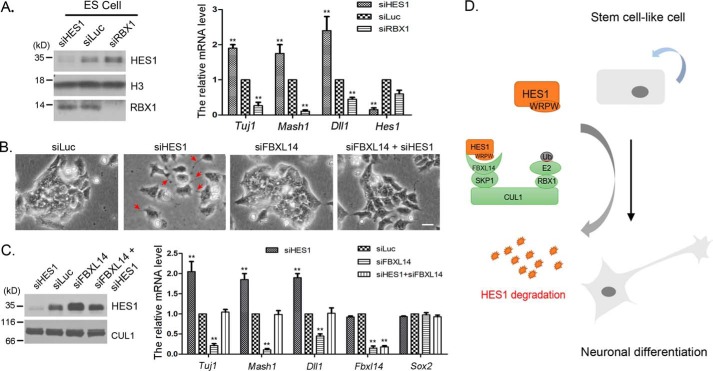

SCFFBXL14-mediated degradation of HES1 stimulates neuronal differentiation

HES1 is highly expressed in ES cell, neural stem cell, and pluripotent tumor cell (such as F9), and its oscillation plays a crucial role in stem cell maintenance, proliferation, and differentiation (47). To investigate whether HES1 degradation mediated by SCFFBXL14 plays a role in ES cell differentiation, we knocked down HES1, RBX1, and FBXL14 in mouse ES and F9 cells, respectively. We found that HES1 knockdown led to a markedly increase of mRNA level of neuron markers, including Mash1 and Tuj1, whereas RBX1 knockdown led to neuron marker genes suppression in mES cells (Fig. 6A). Similar experiments were performed in F9 cells. F9 cells tended to grow in focal clumps. HES1 knockdown resulted in branch-like extension of F9 cells (Fig. 6B, red arrowheads), accompanied by an increased expression of neuron marker genes (Fig. 6C), indicating F9 cells differentiated toward neuron cells. Co-silencing of HES1 and FBXL14 induced the reacquisition of a compact phenotype and blocked the expression of neuron marker genes (Fig. 6, B and C). These data suggest that SCFFBXL14-mediated HES1 degradation promotes neuronal differentiation of stem cell (ES) and stem cell-like cells (F9) (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

The degradation of HES1 mediated by SCFFBXL14 regulated mES cell differentiation. A, HES1 regulated the differentiation of ES cells. Mouse ES cells were transfected with luciferase, RBX1, and HES1 siRNAs for 36 h, and mRNA was isolated. The expression of Tuj1, Mash1, Hes1, and Dll1 were quantified by RT-qPCR). The error bars represent S.D. from three independent experiments. B, co-silencing of FBXL14 reversed the branch-like phenotype induced by HES1 knockdown. F9 cells were transfected with siRNAs as indicated for 48 h, and the representative micrograph is shown. Scale bar, 25 μm. Red arrowheads indicate branch-like structure induced by HES1 knockdown. C, silencing of FBXL14 down-regulated the expression of neuronal marker genes. F9 cells were transfected with siRNAs as indicated for 36 h, and mRNA was extracted. The mRNA levels of Tuj1, Mash1, Dll1, Fbxl14, and Sox2 were quantitated by RT-qPCR. The error bars represent S.D. from three independent experiments. D, schematic diagram for SCFFBXL14 regulating HES1 degradation and cell differentiation. The WRPW motif of HES1 could interacted with FBXL14, which mediated HES1 degradation and promoted stem cell-like cells neural differentiation.

Discussion

SCFFBXL14 acts as the E3 ubiquitin ligase to target HES1 for its degradation

It is believed that the rapid degradation of HES1 by ubiquitin proteasome system is critical for its oscillation. However, little is known about how HES1 stability is regulated by the ubiquitin proteasome system. The identification of E3 ubiquitin ligase for specific substrates has always been difficult, because of the transient interactions, the rapid degradation by the 26S proteasome, and the incompletely defined E3 recognition mechanism (48). Here we show that HES1 proteasome degradation is regulated by SCFFBXL14 ubiquitin ligase. First, the loss of any components of the SCFFBXL14 complex, as well as proteasome inhibition, results in elevated HES1 protein level (Figs. 1–3). Conversely, FBXL14 overexpression enhances HES1 degradation (Fig. 3G). Second, HES1 associates with SKP1, CUL1, and FBXL14 in vivo (Figs. 2D, 3H, and 4B). Third, the SCFFBXL14 complex promotes HES1 ubiquitylation in vivo (Figs. 3I and 4G). Taken together, our results demonstrate that HES1 is a substrate of SCFFBXL14.

FBXL14 has been reported to modulate ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of Mkp3 (mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 3) to regulate vertebrate axis formation in zebrafish (42), suggesting a possible role for SCFFBXL14 to function as a developmental timer. Because the mRNA level of Fbxl14 does not oscillate (Fig. 3J), it is possible that post-translational modification of HES1 protein regulates its recognition by FBXL14. In mammalian cells, FBXL14 has been demonstrated to interact with both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated SNAI1, leading to SNAI1 degradation (39). Whether HES1-specific phosphorylation or other motifs are required for FBXL14 recognition needed to be further determined. Moreover, FBXL14 expression is potently down-regulated during hypoxia, a condition causing an increase of SNAI1 protein rather than its mRNA level (39). In annulus fibrosus cells, HES1 protein level but not its mRNA level was elevated after 24 h of hypoxia (49). However, the underlying mechanism is not fully understood. Because FBXL14 functions as a ubiquitin E3 ligase to promote HES1 degradation, hypoxia-induced down-regulation of FBXL14 may reduce HES1 ubiquitination and degradation in annulus fibrosus cells.

SCFFBXL14-mediated HES1 ubiquitination is necessary for HES1 oscillation

All cultured cells used in our experiments express HES1, but without serum stimulation, HES1 expression level seems to be stationary. In fact, HES1 expression is oscillating at single cell level. In the absence of serum stimulation, HES1 oscillations are just out of synchrony between cells (10, 20). HES1 oscillation was elucidated to be regulated by Notch (12), Jak2-Stat3 (20), BMP, LIF (11) pathways, and miRNA-9 (21, 22) at a transcriptional level. HES1 ultradian oscillation is also regulated by metabolic intermediates such as reactive oxygen species via intracellular calcium signaling (13). Here, we have demonstrated that SCFFBXL14 regulated HES1 oscillation at protein level. Transcriptional auto-suppression and SCFFBXL14-mediated HES1 degradation reach an equilibrium that makes it oscillate with a precise time interval. Alteration of the synthesis and degradation rates changes the period of oscillation (6). Therefore, the fine-tuning of oscillatory behavior of HES1 makes it a rhythmic composer to regulate pluripotent cell (ES, EC, neural stem cell) maintenance, proliferation, and differentiation.

Conserved WRPW motif is required for SCFFBXL14-mediated HES1 degradation

It has been reported that the WRPW motif mediates the proteasome degradation of HES6 (50). The WRPW motif has been shown to be sufficient for acceleration of proteolysis because it fused to two heterologous proteins, the GFP of Aequoria victoria, and Gal4 DNA-binding domain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (50). The WRPW motif is highly conserved among the HES family members. Similarly, our data reveal that the conserved WRPW motif is essential for HES1 degradation (Fig. 4). Deleting the WRPW motif of HES1 weakens the association between HES1 and FBXL14, prevents ubiquitination of HES1, and thereby stabilizes HES1 (Fig. 4).

SCFFBXL14 knockdown represses neuronal differentiation

During embryonic development, HES1 oscillation is required for maintenance of neural stem cells. During neuronal differentiation, HES1 protein level is down-regulated, and its oscillation is damped, which causes up-regulation of proneural factors and directs the neural stem cells toward neuronal differentiation (47). Here, we show that SCFFBXL14 regulates HES1 degradation and oscillation. SCFFBXL14 knockdown led to suppression of neuronal differentiation (Fig. 6). Deletion of FBXL14 has been reported to associate with the neurological disorders (43). Our studies suggest that, to some extent, these phenotypes may be due to aberrantly elevated HES1 levels, because FBXL14-dependent HES1 degradation is significantly impaired by deletion of FBXL14.

In summary, this research solves a long-standing puzzle regarding the regulation of HES1 ubiquitination by demonstrating that SCFFBXL14 targets HES1 for ubiquitination and degradation, which may be indispensable for HES1 oscillation during embryonic development. To our knowledge, this is the first E3 ligase that has been discovered to mediate the regulation of ultradian oscillation. The regulatory mechanism may facilitate our understanding of mouse somitogenesis, neuronal differentiation, and some human neurological disorders.

Experimental procedures

Cell lines and serum stimulation

Mouse embryonic stem cell RW.4, mouse embryonal carcinoma F9 cells, human kidney 293T cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection and cultured as described (51). F9 cells were maintained in DMEM (Gibco REF 11995-065) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. RW.4 cells were cultured in knock-out DMEM (Gibco REF 10829-018) supplemented with 0.1 mm 2-mercaptoethanol (Life Technologies catalog no. 21985-023), 2 mm l-GlutaMAX (Gibco REF 35050-061), 1% non-essential amino acid (Gibco REF 11140-050), 1,000 units/ml mouse LIF (Millipore catalog no. ESG1107), and 15% knock-out serum replacement (Gibco REF 10828-028). For serum stimulation, the cells were starved for 24 h in 0.1% serum, and then serum was supplemented to a final concentration of 10%.

Antibodies, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting

Anti-FLAG antibody (F1804) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Anti-HA (sc-57592), anti-tubulin (sc-5546), goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (sc-2005), goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (sc-2004) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Dallas, TX). Anti-SNAI1 antibody (13099–1-AP) was from Proteintech Group (Wuhan, China), anti-histone H3 antibody (ab1791) was from Abcam (San Francisco, CA), and anti-Ub (3936) was from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-CUL1, anti-CUL4A/CUL4B, and anti-RBX1 antibodies were homemade rabbit polyclonal antibodies as described (52, 53). Anti-HES1 antibody was homemade rabbit polyclonal antibody using 6× His-tagged full-length human HES1 (translation coding AAH39152.1) as the antigen. Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting were performed as described (51).

siRNAs and transfection

For siRNA-mediated silencing, F9 cells were transfected with 50 nm siRNAs for 48 h using DharmaFECT transfection reagent (catalog no. T-2001-03; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). To prevent potential off-target effects of siRNAs, at least two pairs of siRNAs against each gene were designed and used. All of the siRNA experiments were repeated at least three times to ensure consistent results. The cells were transfected with recombinant plasmid by using jetPRIME (catalog no. 114-15; Polyplus-transfection Inc.) for 24–48 h, and the cells were harvested and analyzed. The sequences of the siRNAs are Mouse_RBX1_1, 5′-GGGACAUUGUGGUUGAUAAUU-3′; Mouse_RBX1_2, 5′-AGUGGGAGUUCCAGAAGUAUU-3′; Mouse RBX2, 5′-CCAAAGAAUCGGCAAAUGAUU-3′; Mouse_CUL1_1, 5′-GCAAAGUGCUGAAUGGAAUUU-3′; Mouse_CUL1_2, 5′-ACACAGAGUUUCAGAAUUUUU-3′; Mouse_CUL2, 5′-GCACAACGCCCUCAUUCAAUU-3′; Mouse CUL3, 5′-GAAAGAAACAAGACAGAAAUU-3′; Mouse CUL4A, 5′-GCACGAGUGCGGAGCUGCGUU-3′; Mouse CUL4B, 5′-AAGCCUAAAUUACCAGAAAUU-3′; Mouse CUL5, 5′-CUACUGAACUGGAGGAUUUUU-3′; Mouse CUL7, 5′-GGAAGAAGCCAUUGGAGAAUU-3′; Mouse_HES1, 5′-AGGCGAAGGGCAAGAAUAAUU-3′; Mouse_FBXL14_1, 5′-GCACAGAAACUGGAACUAAUU-3′; Mouse_FBXL14_2, 5′-GCCAGAAACUCACGGAUCUUU-3′; and luciferase, 5′-CUUACGCUGAGUACUUCGAUU-3′.

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted with the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and reverse transcription was performed using a transcription first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Roche). The mRNA levels of the target genes were quantified by real-time PCR using SYBR green (TaKaRa) in an ABI Prism 7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The sequences of the primers used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) are Cul2_Mouse_F, 5′-TGGTCAAAGAACAAGCCCCT-3′; Cul2_Mouse_R, 5′-GCCTAGACTTACCTGAACTCCC-3′; Cul3_Mouse_F, 5′-GTGCACCTTGCTGTGCTTG-3′; Cul3_Mouse_R, 5′-GCCAGCATTGCCCAACAAAT-3′; Cul5_Mouse_F, 5′-CCACGTTTCAGTTGGCTGTG-3′; Cul5_Mouse_R, 5′-AGCATCTGGGAGTTCCGTTG-3′; Cul7_Mouse_F, 5′-GAGCGCGTTCTGGACTACGATA-3′; Cul7_Mouse_R, 5′-AAGTGGGGGATCTTTGGCTTC-3′; Hes1_Mouse_F, 5′-GACGGCCAATTTGCCTTTCTCATC-3′; Hes1_Mouse_R, 5′-TCAGTTCCGCCACGGTCTCCACA-3; Dll1_Mouse_F, 5′-CAGATAACCCTGACGGAGGCTACA-3′; Dll1_Mouse_R, 5′-GGAGGAGGCACAGTCATCCACATT-3′; Tuj1_Mouse_F, 5′-ACGCATCTCGGAGCAGTT-3′; Tuj1_Mouse_R, 5′-CGATTCCTCGTCATCATCTTC-3′; Mash1_Mouse_F, 5′-CCATGAGGAGGATTTCTG-3′; Mash1_Mouse_R, 5′-CGTAGGCTGTTCGTAGTT-3′; Actin_Mouse_F, 5′-GTTACCAACTGGGACGACA-3′; Actin_Mouse_R, 5′-CCAGAGGCATACAGGGAC-3′; Fbxl14_Mouse_F, 5′-CGTTCTGTGACAAGGTGGGA-3′; and Fbxl14_Mouse_R, 5′-GCTCAGGTGCTCAGCGATC-3′.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). For Fbxl14 amplification, 1 μg of total RNA were reverse-transcribed with a Takara PrimeScript RT reagent kit according to the manufacturer's instructions, and 100 ng of cDNA was used as template in semi-quantitative RT-PCR. Actin was taken as a reference gene.

Computational methods

The homology modeling was carried out using Modeler 9.18 software. The structure of the LRR domain (residues 46–400) of FBXL14 was predicted using two ribonuclease inhibitor (RNH1) proteins from different species (Protein Data Bank codes 2BEX and 2BNH) as the templets. The overall sequence identities to the target sequence are both ∼27%. The secondary structures were predicted by SPIDER2. The structure with sequence Ac-SDSMWRPWRN containing the WRPW motif (Protein Data Bank code 2CE9) was then docked into the LRR domain structure using HoDock.

MD simulations were carried out using GROMACS 4.5.4 software with the RSFF2 force field (54). The complex was solvated in an octahedron box (length, 75 Å) of TIP3P water and neutralizing Cl− or Na+ ions. Productive NPT simulation was carried out at 300 K for 150 ns. Structures were recorded every 1.5 ps. Binding free energy in each structure was estimated with the GBSA model using the MMPBSA.py tool from Amber 14. The snapshot with the lowest binding free energy was finally chosen. PyMOL 1.2 was used for protein structure visualization.

Statistical analyses

Paired two-sided Student's t test was performed to measure the significance of statistical difference between the control group and the experimental group. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author contributions

F. L., H. Z., and Y. G. perceived the conception, analyzed the findings, and wrote the manuscript; F. C. and C. Z. designed and executed most of the experiments. F. C. and F. J wrote the manuscript. Y. M. and X. L. assisted in execution of some experiments. H. W., X. G., and F. J. performed theoretical studies. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province Grant 2014A030313779), Shenzhen Science, Technology and Innovation Commission Grant JCYJ20160527100529884, and National Institutes of Health Grant R15GM116087. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- LIF

- leukemia inhibitory factor

- CRL

- Cullin-RING ligase

- CHX

- cycloheximide

- Luc

- luciferase

- LRR

- leucine-rich repeat

- MSCV

- murine stem cell virus

- MD

- molecular dynamics

- RT-qPCR

- real-time quantitative PCR.

References

- 1. Dunlap J. C. (1999) Molecular bases for circadian clocks. Cell 96, 271–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schibler U., and Sassone-Corsi P. (2002) A web of circadian pacemakers. Cell 111, 919–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tyson J. J., Chen K., and Novak B. (2001) Network dynamics and cell physiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 908–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paszek P., Ryan S., Ashall L., Sillitoe K., Harper C. V., Spiller D. G., Rand D. A., and White M. R. (2010) Population robustness arising from cellular heterogeneity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11644–11649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pourquié O. (2003) The segmentation clock: converting embryonic time into spatial pattern. Science 301, 328–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hirata H., Yoshiura S., Ohtsuka T., Bessho Y., Harada T., Yoshikawa K., and Kageyama R. (2002) Oscillatory expression of the bHLH factor Hes1 regulated by a negative feedback loop. Science 298, 840–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bessho Y., and Kageyama R. (2003) Oscillations, clocks and segmentation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13, 379–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hirata H., Bessho Y., Kokubu H., Masamizu Y., Yamada S., Lewis J., and Kageyama R. (2004) Instability of Hes7 protein is crucial for the somite segmentation clock. Nat. Genet. 36, 750–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jouve C., Palmeirim I., Henrique D., Beckers J., Gossler A., Ish-Horowicz D., and Pourquié O. (2000) Notch signalling is required for cyclic expression of the hairy-like gene HES1 in the presomitic mesoderm. Development 127, 1421–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Masamizu Y., Ohtsuka T., Takashima Y., Nagahara H., Takenaka Y., Yoshikawa K., Okamura H., and Kageyama R. (2006) Real-time imaging of the somite segmentation clock: revelation of unstable oscillators in the individual presomitic mesoderm cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 1313–1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kobayashi T., Mizuno H., Imayoshi I., Furusawa C., Shirahige K., and Kageyama R. (2009) The cyclic gene Hes1 contributes to diverse differentiation responses of embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 23, 1870–1875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shimojo H., Ohtsuka T., and Kageyama R. (2008) Oscillations in notch signaling regulate maintenance of neural progenitors. Neuron 58, 52–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ventre S., Indrieri A., Fracassi C., Franco B., Conte I., Cardone L., and di Bernardo D. (2015) Metabolic regulation of the ultradian oscillator Hes1 by reactive oxygen species. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 1887–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kageyama R., Ohtsuka T., and Kobayashi T. (2007) The Hes gene family: repressors and oscillators that orchestrate embryogenesis. Development 134, 1243–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shimojo H., Ohtsuka T., and Kageyama R. (2011) Dynamic expression of notch signaling genes in neural stem/progenitor cells. Front. Neurosci. 5, 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ishibashi M., Ang S. L., Shiota K., Nakanishi S., Kageyama R., and Guillemot F. (1995) Targeted disruption of mammalian hairy and Enhancer of split homolog-1 (HES-1) leads to up-regulation of neural helix-loop-helix factors, premature neurogenesis, and severe neural tube defects. Genes Dev. 9, 3136–3148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakamura Y., Sakakibara S., Miyata T., Ogawa M., Shimazaki T., Weiss S., Kageyama R., and Okano H. (2000) The bHLH gene hes1 as a repressor of the neuronal commitment of CNS stem cells. J. Neurosci. 20, 283–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kobayashi T., and Kageyama R. (2011) Hes1 oscillations contribute to heterogeneous differentiation responses in embryonic stem cells. Genes (Basel) 2, 219–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baek J. H., Hatakeyama J., Sakamoto S., Ohtsuka T., and Kageyama R. (2006) Persistent and high levels of Hes1 expression regulate boundary formation in the developing central nervous system. Development 133, 2467–2476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yoshiura S., Ohtsuka T., Takenaka Y., Nagahara H., Yoshikawa K., and Kageyama R. (2007) Ultradian oscillations of Stat, Smad, and Hes1 expression in response to serum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 11292–11297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bonev B., Stanley P., and Papalopulu N. (2012) MicroRNA-9 modulates Hes1 ultradian oscillations by forming a double-negative feedback loop. Cell Rep. 2, 10–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li S., Liu Y., Liu Z., and Wang R. (2016) Neural fate decisions mediated by combinatorial regulation of Hes1 and miR-9. J. Biol. Phys. 42, 53–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kobayashi T., Iwamoto Y., Takashima K., Isomura A., Kosodo Y., Kawakami K., Nishioka T., Kaibuchi K., and Kageyama R. (2015) Deubiquitinating enzymes regulate Hes1 stability and neuronal differentiation. FEBS J. 282, 2411–2423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Skaar J. R., Pagan J. K., and Pagano M. (2013) Mechanisms and function of substrate recruitment by F-box proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 369–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Duong H. A., Robles M. S., Knutti D., and Weitz C. J. (2011) A molecular mechanism for circadian clock negative feedback. Science 332, 1436–1439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Takahashi J. S., Hong H. K., Ko C. H., and McDearmon E. L. (2008) The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: implications for physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 764–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Busino L., Bassermann F., Maiolica A., Lee C., Nolan P. M., Godinho S. I., Draetta G. F., and Pagano M. (2007) SCFFbxl3 controls the oscillation of the circadian clock by directing the degradation of cryptochrome proteins. Science 316, 900–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hirano A., Yumimoto K., Tsunematsu R., Matsumoto M., Oyama M., Kozuka-Hata H., Nakagawa T., Lanjakornsiripan D., Nakayama K. I., and Fukada Y. (2013) FBXL21 regulates oscillation of the circadian clock through ubiquitination and stabilization of cryptochromes. Cell 152, 1106–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nakayama K. I., and Nakayama K. (2005) Regulation of the cell cycle by SCF-type ubiquitin ligases. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 323–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nakayama K. I., and Nakayama K. (2006) Ubiquitin ligases: cell-cycle control and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 369–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nishitani H., Sugimoto N., Roukos V., Nakanishi Y., Saijo M., Obuse C., Tsurimoto T., Nakayama K. I., Nakayama K., Fujita M., Lygerou Z., and Nishimoto T. (2006) Two E3 ubiquitin ligases, SCF-Skp2 and DDB1-Cul4, target human Cdt1 for proteolysis. EMBO J. 25, 1126–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koepp D. M., Harper J. W., and Elledge S. J. (1999) How the cyclin became a cyclin: regulated proteolysis in the cell cycle. Cell 97, 431–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vucic D., Dixit V. M., and Wertz I. E. (2011) Ubiquitylation in apoptosis: a post-translational modification at the edge of life and death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 439–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sun Y. (2003) Targeting E3 ubiquitin ligases for cancer therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2, 623–629 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sundqvist A., Bengoechea-Alonso M. T., Ye X., Lukiyanchuk V., Jin J., Harper J. W., and Ericsson J. (2005) Control of lipid metabolism by phosphorylation-dependent degradation of the SREBP family of transcription factors by SCF(Fbw7). Cell Metab. 1, 379–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Skowyra D., Craig K. L., Tyers M., Elledge S. J., and Harper J. W. (1997) F-box proteins are receptors that recruit phosphorylated substrates to the SCF ubiquitin-ligase complex. Cell 91, 209–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jin J., Cardozo T., Lovering R. C., Elledge S. J., Pagano M., and Harper J. W. (2004) Systematic analysis and nomenclature of mammalian F-box proteins. Genes Dev. 18, 2573–2580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang Z., Liu P., Inuzuka H., and Wei W. (2014) Roles of F-box proteins in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 233–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Viñas-Castells R., Beltran M., Valls G., Gómez I., García J. M., Montserrat-Sentís B., Baulida J., Bonilla F., de Herreros A. G., and Díaz V. M. (2010) The hypoxia-controlled FBXL14 ubiquitin ligase targets SNAIL1 for proteasome degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3794–3805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fang X., Zhou W., Wu Q., Huang Z., Shi Y., Yang K., Chen C., Xie Q., Mack S. C., Wang X., Carcaboso A. M., Sloan A. E., Ouyang G., McLendon R. E., Bian X. W., et al. (2017) Deubiquitinase USP13 maintains glioblastoma stem cells by antagonizing FBXL14-mediated Myc ubiquitination. J. Exp. Med. 214, 245–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lander R., Nordin K., and LaBonne C. (2011) The F-box protein Ppa is a common regulator of core EMT factors Twist, Snail, Slug, and Sip1. J. Cell Biol. 194, 17–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zheng H., Du Y., Hua Y., Wu Z., Yan Y., and Li Y. (2012) Essential role of Fbxl14 ubiquitin ligase in regulation of vertebrate axis formation through modulating Mkp3 level. Cell Res. 22, 936–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Abdelmoity A. T., Hall J. J., Bittel D. C., and Yu S. (2011) 1.39 Mb inherited interstitial deletion in 12p13.33 associated with developmental delay. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 54, 198–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gong X., Liu B., Chang S., Li C., Chen W., and Wang C. (2010) A holistic molecular docking approach for predicting protein-protein complex structure. Sci. China Life Sci. 53, 1152–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gong X., Wang P., Yang F., Chang S., Liu B., He H., Cao L., Xu X., Li C., Chen W., and Wang C. (2010) Protein-protein docking with binding site patch prediction and network-based terms enhanced combinatorial scoring. Proteins 78, 3150–3155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wagner S. A., Beli P., Weinert B. T., Nielsen M. L., Cox J., Mann M., and Choudhary C. (2011) A proteome-wide, quantitative survey of in vivo ubiquitylation sites reveals widespread regulatory roles. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 10, M111.013284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Imayoshi I., Isomura A., Harima Y., Kawaguchi K., Kori H., Miyachi H., Fujiwara T., Ishidate F., and Kageyama R. (2013) Oscillatory control of factors determining multipotency and fate in mouse neural progenitors. Science 342, 1203–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kitagawa K., and Kitagawa M. (2016) The SCF-type E3 ubiquitin ligases as cancer targets. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 16, 119–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hiyama A., Skubutyte R., Markova D., Anderson D. G., Yadla S., Sakai D., Mochida J., Albert T. J., Shapiro I. M., and Risbud M. V. (2011) Hypoxia activates the notch signaling pathway in cells of the intervertebral disc: implications in degenerative disc disease. Arthritis Rheum. 63, 1355–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kang S. A., Seol J. H., and Kim J. (2005) The conserved WRPW motif of Hes6 mediates proteasomal degradation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 332, 33–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yin F., Lan R., Zhang X., Zhu L., Chen F., Xu Z., Liu Y., Ye T., Sun H., Lu F., and Zhang H. (2014) LSD1 regulates pluripotency of embryonic stem/carcinoma cells through histone deacetylase 1-mediated deacetylation of histone H4 at lysine 16. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34, 158–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Higa L. A., Banks D., Wu M., Kobayashi R., Sun H., and Zhang H. (2006) L2DTL/CDT2 interacts with the CUL4/DDB1 complex and PCNA and regulates CDT1 proteolysis in response to DNA damage. Cell Cycle 5, 1675–1680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Higa L. A., Wu M., Ye T., Kobayashi R., Sun H., and Zhang H. (2006) CUL4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase interacts with multiple WD40-repeat proteins and regulates histone methylation. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1277–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhou C. Y., Jiang F., and Wu Y. D. (2015) Residue-specific force field based on protein coil library. RSFF2: modification of AMBER ff99SB. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 1035–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]